A worrying amount of credit and blame for the course of my life probably goes to 1995’s Dark Forces. It’s the first of the series of shooters that LucasArts made, and it’s probably the one people talk about least. Jedi Knight, which came out a couple years later, was an instant classic, and in its wake the rest of the series grew less-and-less interested in being a shooter and instead focused the action on lightsabers and Jedi powers. Dark Forces, which could be and often was reduced to “Star Wars Doom”, shrank in comparison to its more popular and respected successors.

That’s unfair to what was in many ways a special and forward-looking game, one whose level design is as likely to call to mind Looking Glass’s Thief as it is Doom. Before the first person shooter was the ubiquitous and varied genre it is today, which includes everything from Counter-Strike to Deus Ex, these games were called " Doom clones." Many earned that designation since they barely changed a hugely successful formula, but Dark Forces was one of the first to show the genre had a lot more to offer than cramped corridors and snarling imps.

Dark Forces looms large in my memory because for so long it occupied an outsize share of my imagination. It went from gaming magazine fetish-object to desperately wished-for Christmas gift to infuriating PC gaming debacle and finally, about a year after it came out, after forming a relationship with it full of fascination and resentment, I finally got a chance to play it.

I can’t remember when I first heard about Dark Forces, but I know the obsession began with Computer Gaming World’s reservedly positive review. Jason Kapalka opened his review with an anecdote about a Star Wars-obsessed friend who had recently dropped a couple hundred dollars on an unopened and charmless Star Wars action figure from the Empire Strikes Back era. Kapalka, dismayed, asked his perpetually cash-strapped friend what the hell he was thinking spending that much money on a toy Luke Skywalker. His friend answered, “Well, it’s Star Wars, innit?”

Kapalka:

I opened my mouth, then shut it again. What could I say? To him, that viciously overpriced vacuum-mold widget WAS Star Wars… a film nearly 20 years old that’s still a monstrously lucrative franchise, and something more than that: it’s perhaps this generation’s most potent and pervasive pop mythology.

My father and I shared our subscription to CGW, and he tended to push back on my flights of enthusiasm. He didn’t like Star Wars and he didn’t much care for my increasing obsession with it, but beyond that he knew I would only get about two full-price game purchases each year and they needed to be winners. He read the Dark Forces review and zeroed-in on the passage where Kapalka called it a Doom clone. He didn’t understand why, after years of Wolfenstein 3D and Doom, I needed more of the same.

But he didn’t get the point of the story Kapalka told. In that opening, you either identified with Kapalka, or with his friend. Your reaction to the anecdote would inflect how you read the rest of the review, almost turning it into two different reviews for two different audiences. Dad saw a review for a derivative, slickly-themed shooter of incremental advancement over id’s masterpiece. I saw a review for a game that would grant me passage to the Star Wars universe.

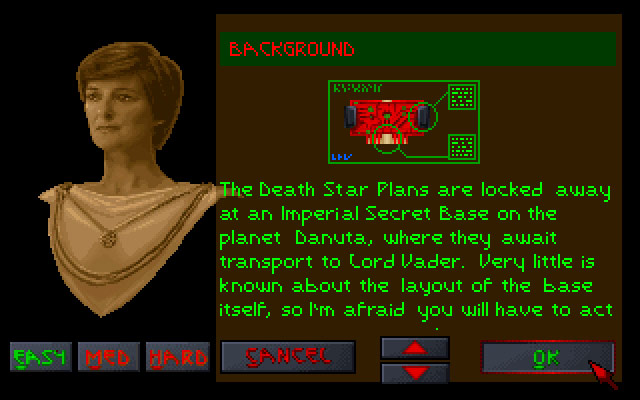

Dark Forces came out in February of 1995, but I got it for Christmas that year. For 10 months, I thought about that game. I re-read that review. I looked at screenshots in strategy guides (but didn’t read the guides themselves because I wanted to discover the game for myself). I memorized the list of new weapons and enemies. The hyper-dangerous Concussion Rifle sounded awesome, the Imperial Repeating Rifle sounded sensible.

Ten months of obsession led up to my all-time worst PC gaming experience: when I finally got Dark Forces in my hands, the game didn’t launch. It installed just fine, but when I launched the executable, nothing happened. The CD drive didn’t make it’s reassuring whirring-grinding noise, the hard drive didn’t make any of its noisy ticks. The computer paused for a moment, and then gave me a fresh, blank C:\ prompt.

Nightmarishly, my cousin had also gotten the game and for the next few weeks when we talked, he cheerfully related how awesome Dark Forces was. Meanwhile, weeks of tinkering, testing connections, and ritualistic reinstalls didn’t change the fact that Dark Forces, and only Dark Forces, would not run on my computer.

Months later, my parents finally called-in Nipul.

Nipul was the Mr. Wolf of my early days of PC gaming—a fixer. A classmate of my mom’s at Purdue Cal, where they were getting their bachelor’s taking night classes, Nipul graduated and immediately started a PC repair business. His margins were huge, probably unconscionable in retrospect (we got the “friend discount” that brought them down to “eye-popping”) but it was the mid-90s and Nipul could charge whatever he wanted because he was a “computer guy” at a time when that kind of enthusiasm and knowledge could confer unchallengeable authority. He was also, and this is what I most appreciated about him, someone who believed in the upsell as a moral imperative. Whatever specs you came into the shop thinking about, he knew that kicking it up a notch would make everyone happier in the long run.

I don’t know what he fixed or how. I do know that on a rainy night in the autumn of 1996, he dropped by the house to deliver our re-built PC. It had a new CD drive, more memory, and generally ran like a dream. It sounded different when I turned it back on. He promised me that Dark Forces was now installed, and he’d verified it worked.

I played Dark Forces the rest of the night, the sound of blaster fire and the affected, flat shouts of stormtroopers mingling with the sound of the rain running off leaves and into the gutters above the PC room.

Did it live up to the dream? At the time I thought it did. You had to use your imagination a little. I was dead certain the enemy AI was more life-like than anything I’d ever seen before, that the Imperials used tactics in a way your common Doom enemies never did. Playing it now, I realize that the enemies seem more prone to wandering toward you in a way that approximates flanking, but is clearly no such thing. Combined with some clever placement, and Dark Forces could make you think your opponents were crafty, or had a reaction process that went beyond, “See, shoot, chase.”

But Doom never gave me a feeling like Dark Forces did. On a rocky ledge hugging the face of a chalk-cliff, with a shrieking wind whipping through the canyons around me, I realized the path was becoming so narrow I had to look down to see where to take my next steps. I hit PgUp and the camera ratcheted down from eye-level and the cold sky above is replaced by the dull gray smear of the ledge and the bone-white expanse of the cliff. Then I saw them, so incredibly far away down on the floor of the canyon that they were just shimmering smears of white and brown pixels. A stormtrooper squad arrayed in formation behind an Imperial officer. I pulled a thermal detonator and followed its long arc all the way down to the ground, where it exploded in their midst and dropped the officer and two troopers immediately. Then I rained more down on the survivors heads.

Dark Forces evoked a sense of place more than any shooter I’d played at the time. It let me walk around inside the Star Wars universe in a way we’d never been able to before, and get into the kind of frenetic blaster duels we’d seen aboard the Death Star in the original movie. It was crudely done, but the iconography was so powerful that the illusions came together. If you walked into a giant room and there was a rectangular slab running along one wall with a blur or pixelated strip-lighting around it, and little alcoves cut into the wall of the next room, you knew you were in a cantina. If you were in a sewer and one of those eye-stalk monsters popped out, it was a Star Wars Sewer. And if you saw a bunch of little white-armored sprites standing stock-still behind an Imperial officer, like those cut-outs of Rebel troops at the end of A New Hope, you could pretend it was a squad of Imperial troops awaiting orders from their CO, and not just a bunch of simple enemies waiting for you enter their detection radius so they could start going through the motions of trying to kill you.

It’s where that CGW review seems most dated: Kapalka could see and inventory all the ways that Dark Forces moved level design beyond anything we’d seen in Doom, but couldn't concede that in the process it had become something distinct from Doom. The sprawling levels of Dark Forces, replete with spaces that heavily implied function (water turbines, prison complexes, deep mine shafts) felt less like the discrete levels of earlier shooters and more like functional models of places that could easily be real. When breaking General Madine out of an Imperial detention cell, I was floored when I realized that the key to getting through security was to call an elevator car to a different floor, and then use the now-empty elevator shaft to break-in.

But I think it was Dark Forces’ most bizarre decision that cemented my relationship with those spaces: You couldn’t save. You had a set number of “lives” to get through each level, but once you committed to these giant Star Wars dioramas, you had to finish the level in a single session. It was inconvenient and a huge pain in the ass but… it also created a level of tension that the save-scumming rhythm of Doom could never sustain. Every one of those levels, with their treacherous falls and cleverly hidden ambushes, demanded a careful, methodical approach. I remember the last level took me about four hours, and I was down to 50 percent life and no shields when I entered a huge combat arena, the lights came down, and a menacing Imperial general’s voice boomed-out, “It’s been a long time since I’ve challenged a man…” The huge, silhouetted shape of his enhanced body armor appeared in a doorway, and the final fight of the game began, with no option but to replay the entire crushingly-difficult level again if I lost. I won, and it became one of the greatest boss battles I’ve ever played. If it had gone the other way, I would probably still be fuming about it.

That’s maybe the last reason I often find myself thinking back fondly on Dark Forces. It made the kind of weird choices that are harder to make after genre expectations have been codified. Twenty-five years later, “run-based” games are more respected and appreciated, but Dark Forces was tacking into a headwind of convenience features that became all-but-mandatory across shooter design.

Now, of course, all that friction is what I’m nostalgic for. Not just in the game, but what was around the game. Gaming magazines didn’t just stoke rabid enthusiasm, but provided snapshots of where games were at, and how different were the places they were going. In a year of PC gaming, what games looked and felt like could change completely. To get excited about a game was to get excited about the future it was a part of. For a long time, long after the game came out and most people were able to play it, Dark Forces felt like the future.

from VICE https://ift.tt/2v4M1T0

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment