Kenneth Billman turned on the television in the summer of 2013 in his Mountain View, California, home to a story that had become familiar to local residents: wildfires were threatening life and limb across the state at an unprecedented rate. That year, almost 10,000 fires burned 600,000 acres of land in California, causing over $200 million in damage.

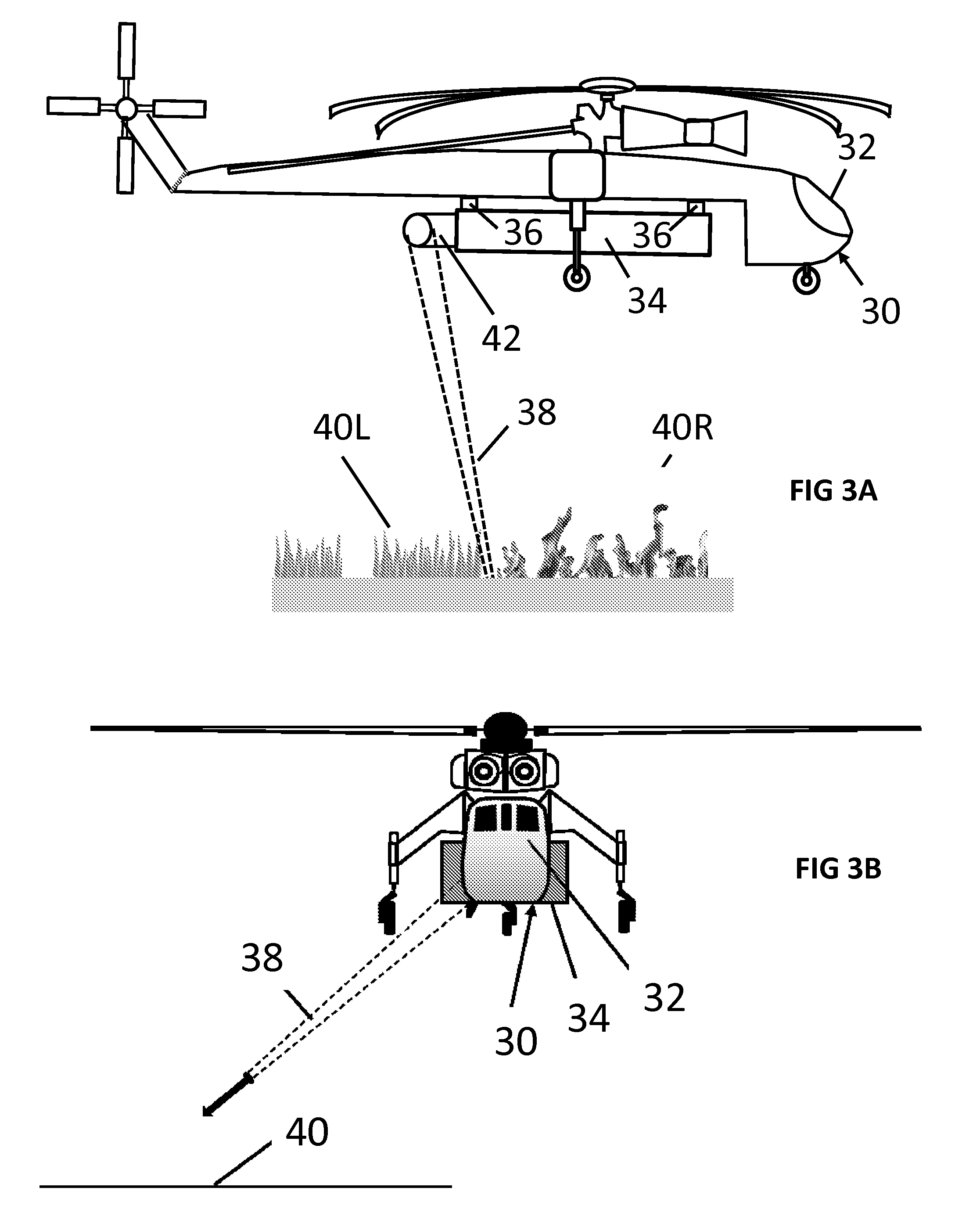

Worried about the devastation the fires were causing, Billman got to work doing what any sane, recently retired, 80-year-old laser scientist would do. He drafted a concept for what he thought would stamp out the problem of wildfires forever—a powerful flying laser. His patent application, “Laser System Module-Equipped Firefighting Aircraft,” details designs for laser modules that could fit on helicopters, planes, or small drones. The lasers would start controlled burns from the air to remove the grasses and brush that provide fuel for fires.

Firefighters have long been fighting fire with fire. When a wildfire breaks out in a national forest, the U.S. Forest Service sends teams of “hotshot crews” to create firelines to stop the spread of a fire. These groups of 20 men and women use shovels and axes to clear debris. They also use drip torches—cannisters filled with gelled gasoline—to start fires. It’s dangerous and time consuming work.

It can be safer to start a fire from the air. A helitorch—basically a flying flamethrower—has been used by the Forest Service since 2015. They use these flying buckets of gas for what is called aerial ignition.“Aerial ignition is used for prescribed wildfire treatments and for calculated ‘burn out’ operations,” said Jessica Gardetto, the external affairs chief at the National Interagency Fire Center.

“What you’re trying to do is remove anything that’s flammable,” said Heather Alexander, assistant professor of Forest Ecology at Auburn University. The key is to intentionally ignite the natural fuels that feed a fire downwind of it, in the direction the fire is moving. A fire will slow and hopefully stop once it reaches the burn out area.

Gardetto wouldn’t comment on if a high power laser could work to start a backfire. “We can’t really say much about whether they’ll be useful until we have solid, federally-approved data showing effectiveness,” she wrote.

Another “aerial ignition” technology commonly used are one inch fuel-filled pods that can be dropped in a line from a small drone. According to the National Wildfire Coordination Group Standards for Aerial Ignition, these plastic spheres are cheaper and have less complicated safety protocols than helitorches.

A high power laser on a helicopter could be a very precise and effective alternative to these aerial ignition techniques.

“The beauty part here is that you don’t need an exquisite system for end point maintenance like you do in defense applications,” said Mark Neice, executive director of the Directed Energy Professional Society. Neice, a retired Air Force Colonel, has spent his career procuring high power laser weaponry. “If you’re just trying to light the forest up and set up a back burn, the precision required for that application is not nearly as restrictive as something I’d be looking for,” in a military system, he said.

Billman had a similar thought when he got the idea to fight fires with lasers. He had spent the past two decades coaxing a flying laser weapon, the Airborne Laser, from improbable PowerPoint fantasy to no-big-deal reality in a quietly successful test demonstration that swatted an intercontinental ballistic missile out of the sky…with photons. I met Billman while working at Lockheed Martin as an engineer on an upgrade to one of the Airborne Laser’s components, and have long been fascinated by the outlandishness of the program. The complex system of lasers and optics called the Airborne Laser was installed on a highly modified Boeing 747. The device had to find, track, lock onto, and destroy a very fast moving target from very far away. Billman designed a correction system to ensure all the coherent light could get to the missile without breaking up in the atmosphere. The laser plane program was shuttered in 2014 a few years after a series of tests that proved it was viable.

Something like the Airborne Laser, a megawatt-class apparatus, would be beyond overkill for what’s needed to start a fire from the sky. The Department of Defense has been exploring more agile alternatives to the Airborne Laser. The Air Force’s SHiELD program aims to put a 60 kilowatt laser onto fighter aircraft, with a maximum weight of 4,200 pounds.

Weight is important when you’re putting large lasers on planes. A laser used for firefighting could be swapped out with large tanks of water and fire retardant that are used to fight fires. A Sikorsky S-64 helicopter, which is regularly used to fight fires, can carry payloads of 22,000 pounds—enough for a fairly powerful laser.

A 60 kilowatt laser isn’t necessary to start backfires. Ten or 20 kilowatts would be enough for this application, said Neice. Although the technology you’d need to build a firefighting laser plane is more or less readily available, developing it could take several years and cost tens of millions of dollars, he said.

There are also regulatory and safety concerns that need to be addressed for a firefighting laser. Lasers can be extremely dangerous, especially powerful ones flying through the air. The Federal Aviation Administration is concerned about people pointing laser pointers at planes. Laser pointer power is measured in milliwatts, a million times weaker than a kilowatt-class laser. One thing that reduces risk is that a fire-starting laser would point at the ground, not the sky. The biggest danger is probably to people’s eyes. Most high power lasers developed for the military operate at a wavelength of one micron, which is a sweet spot for causing eye damage. Firefighters located near an operational laser would need eye protection.

Gardetto says that the process of getting approval for a new aerial ignition technology varies depending on the device. The federal government would need to work closely with anyone who dares take on the task of building Billman’s firefighting laser, to ensure it is safe.

After finishing his patent application, Billman brought the idea to his former employer, as well as other laser manufacturers and component suppliers he knew from a fifty year plus career. He hoped to share the rights with a company willing to fund a prototype. They all turned him down.

“All they understand is cost-plus fixed fee,” he said, referring to an arrangement defense contractors make with the government to fund all research, development, and manufacturing costs. A 5 to 10 percent fee is added as a guaranteed profit. It’s difficult to convince defense companies to invest their own money in something that may not pan out.

Billman eventually gave up on building his laser plane. He withdrew his patent application, but still thinks it’s a good idea. “My hope is to see the concept demonstrated to show that these terrible wildfires can be more quickly stopped by remote and safe backfire setting,” he said.

from VICE US https://ift.tt/3mvpFjv

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment