VICE's #BlackLove series celebrates the bonds between Black people through intimate, powerful, and uplifting narratives of love in all its forms. Through these stories, we honor the art, activism, and beauty that grows from black love.

Popular culture holds an affinity for positioning love as an intangible, amorphous feeling; something impossible to convey. It’s a smart tactic—saying love is difficult to capture gives allowance for incessant tries (i.e. films, TV shows, books, songs) at capturing it.

Brooklyn-based photographer Keisha Scarville avoids this move. She distills love down to the simplest of expressions. Her late-mother’s shawl, for example, is love. Her father’s old passport, too. Born to Guyanese immigrant parents, Scarville's tenderhearted odes to her parents illustrate it is possible to communicate love succinctly and profoundly, but only if you’re willing to do the long, hard emotional labor required.

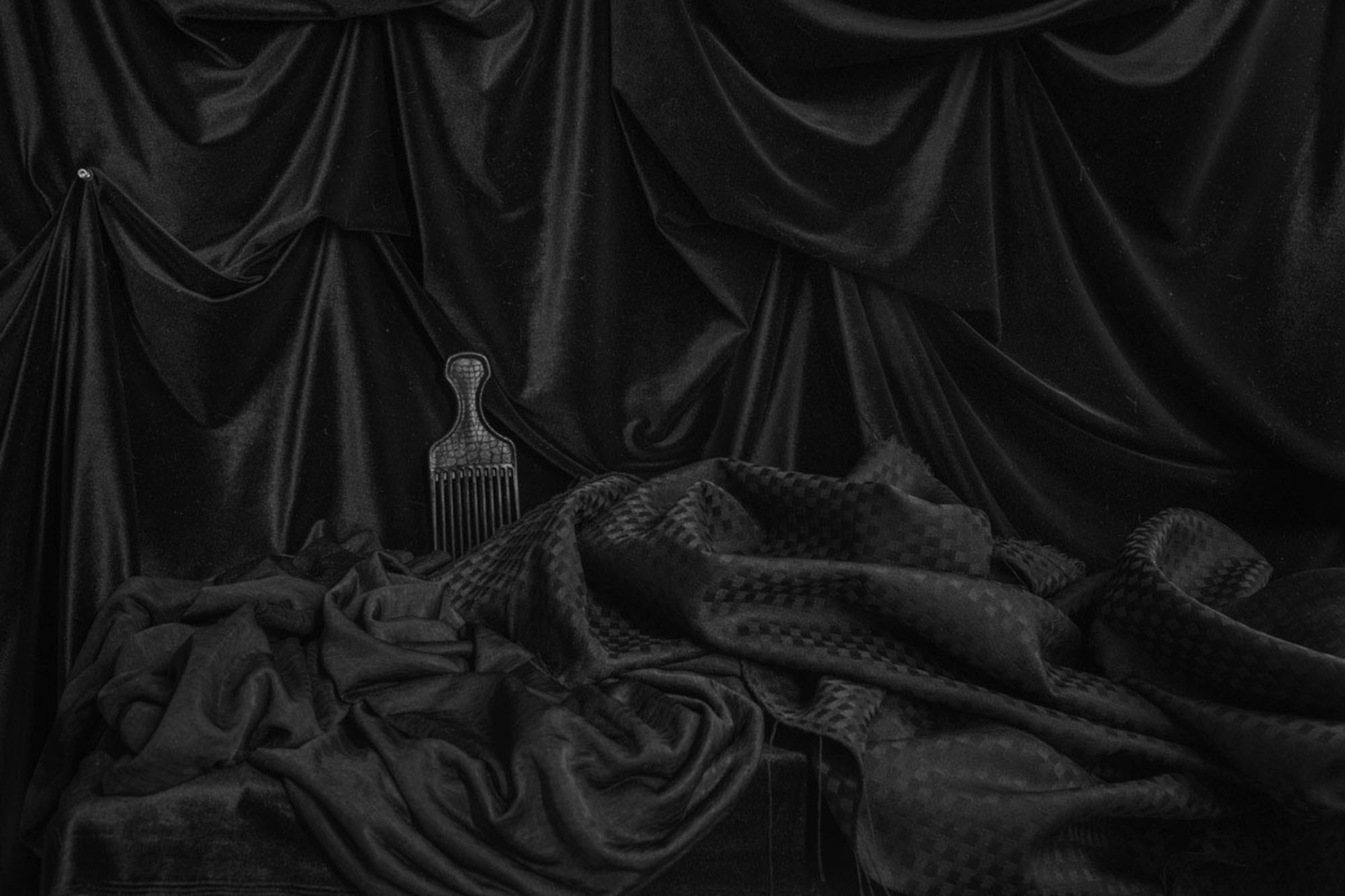

Case in point: The three years Scarville spent creating her moving series, Mama’s Clothes. She used the project to process and heal after her mother passed away from colon cancer in 2015. Those years were spent digging through her mother’s clothes and capturing herself wearing them. In the beautifully somber photos, fabrics cover Keisha’s face and obscure her identity. There is the poignant feeling that losing her mother has caused Keisha to lose herself.

“There definitely is a practice of love when I make images,” Scarville tells VICE. She says she is interested in the ways we function when we lose someone close to us, how we lose ourselves even. “For me, love is how I allow myself to freely fill the frame.” Her exploration of absence, paradoxically, illustrates that even after our deaths we linger around through the ones we loved.

Here, Keisha talks to VICE about the lessons on black love her parents taught her, wearing her late-mother’s clothes, and Diana Ross and Billy Dee Williams.

VICE: Tell me a little about yourself and your work.

Keisha Scarville: I was born and raised in Brooklyn to Caribbean parents. I spent most of my childhood going back and forth between Brooklyn and Guyana. The country basically experienced an exodus of people in the 60s—many coming to the States, England, and Canada. So, geographically, I grew up between Brooklyn and Guyana.

VICE: What did your parents teach you about black love?

Scarville: My parents, especially my dad, were Garveyites. They held Marcus Garvey—the civil rights leader from Jamaica—in high esteem. Marcus Garvey was a big advocate of Pan-Africanism and understanding how Africa plays a role in black people understanding ourselves. So a lot of my ideas about black solidarity and consciousness came from my parents.

VICE: I love the series Mama’s Clothes. There’s a strange note of sadness to it as you explore your love for your mother. Can you tell me a little more about the project?

Scarville: My mother was diagnosed with Stage IV colon cancer in August 2014. Then she passed on August 13, 2015. Mama’s Clothes was prompted from a place of wanting to understand how I can create images of someone who is no longer here. The photographs became a documentation of absence.

I started the series almost immediately after she passed. It was my way of processing. The entire series was a three-year endeavor. There was no deadline—everything was motivated by me. It was extremely liberating to develop a project and not have any pressure from outside forces.

VICE: Do you think the project took so much time because the healing process takes so much time?

Scarville: Yes, kind of. I also spent a good time doing a lot of research into spirit photography, exploring different cultures and how they look at absence. There was also process of going through my mother’s things. Figuring out where does all this stuff go when the person is no longer here? Her inanimate objects held a biological aspect to them. There was a smell in her clothes.

VICE: Could you describe that smell?

Scarville: Oh, that’s hard! A combination of soul, and salt, and honey, and love.

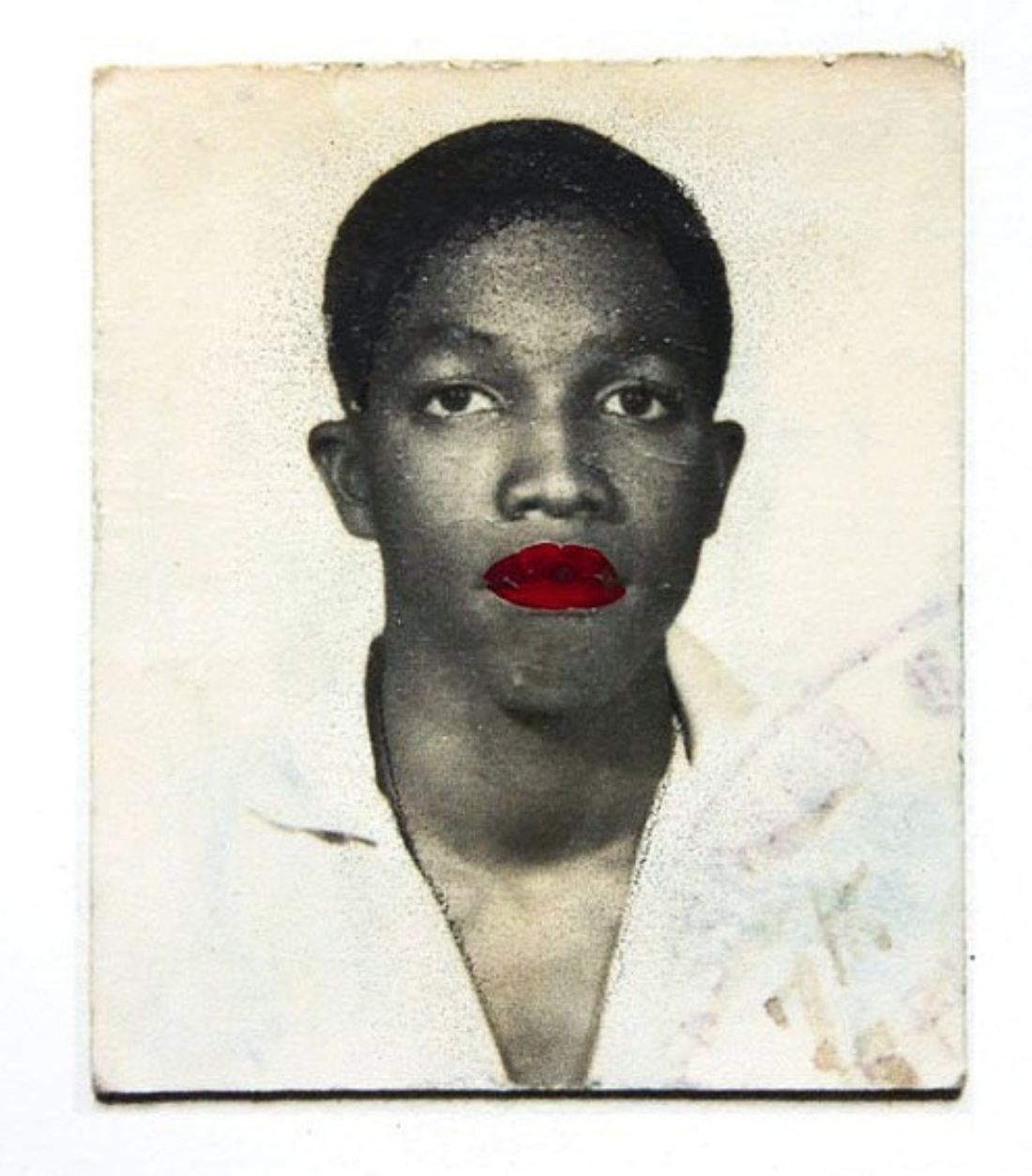

VICE: What are you exploring in the series Passports? What really interests me is how you manipulate your father’s image. It feels like you are playing around with his identity.

Scarville: I was doing a series of interviews with my parents about Guyana and their ideas about belonging. My dad mentioned he no longer saw Guyana as his home. That he identified fully as an American now. Then he showed me his very first passport, which is from when he was 16. I became fascinated with the way the passport is organized and the regulations involved with creating a passport photo.

I did about a hundred reproductions of my dad’s passport photo. In each one I wanted to symbolically tell his story. Each one is influenced about the stories he told me about coming from Guyana to America. His passport image became a way to excavate those stories and narratives.

VICE: What about the photos where you paint feminine qualities, like lipstick and pearls, on to his images?

Scarville: In some, I’m thinking about how his journey has affected me. So in some, I’m kind of mashing together both of our identities. There’s lipstick or a feminine approach to how I’m treating the image. How my identity is impacted by my dad.

VICE: And the one that really strikes me is where your father’s eyes and mouth are painted white. The act feels violent.

Scarville: So in that one I’m using whiteout. I think for my dad, and coming here, coming from being an Afro-Guyanese and then being embedded here and immediately perceived as a black man in the 1960s—and that other layer of being Caribbean—impacting how people saw him… but also didn’t see him. How people heard his accent, and then didn’t hear him. Thinking about how your presence is punctuated, but also how your presence might also be ignored. How your invisibility plays off your hypervisibility.

VICE: When I think about black love, a lot of 90s films like How Stella Got Her Groove Back and even sitcoms like Martin and The Parkers stick out in my memory. What examples of black love in the media helped shape you growing up?

Scarville: It’s hard for me to speak to the current without speaking about the images I grew up with. I remember one of the first images of black love I grew up with is Diana Ross and Billy Dee Williams. There was something about seeing their relationship play out in Lady Sing the Blues and Mahogany. Looking at Diana play off Billy in Mahogany,

where there’s this shared understanding of struggle and investment in each other. They make space for each other’s aspirations. There was something really beautiful about seeing that as a child.

VICE: What are your thoughts on how black love is currently represented in media?

Scarville: I think, sometimes, the way black love is portrayed in the media is very shallow. Then there’s times where I see it done in a way that’s very complex and nuanced. I saw If Beale Street Could Talk, and I’ll be honest, I thought there were things the movie gets right, but I also thought there were things that it gets wrong—like the development of the characters’ roles.

I look forward to the times when those depictions are just normalized. When they are not seen as an event. But maybe those depictions aren’t normalized yet because there is still so much violence against our bodies.

See more work from Keisha Scarville below. You can follow her here.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow André Wheeler on Instagram.

from VICE http://bit.ly/2GGwLPR

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment