This article originally appeared on VICE UK.

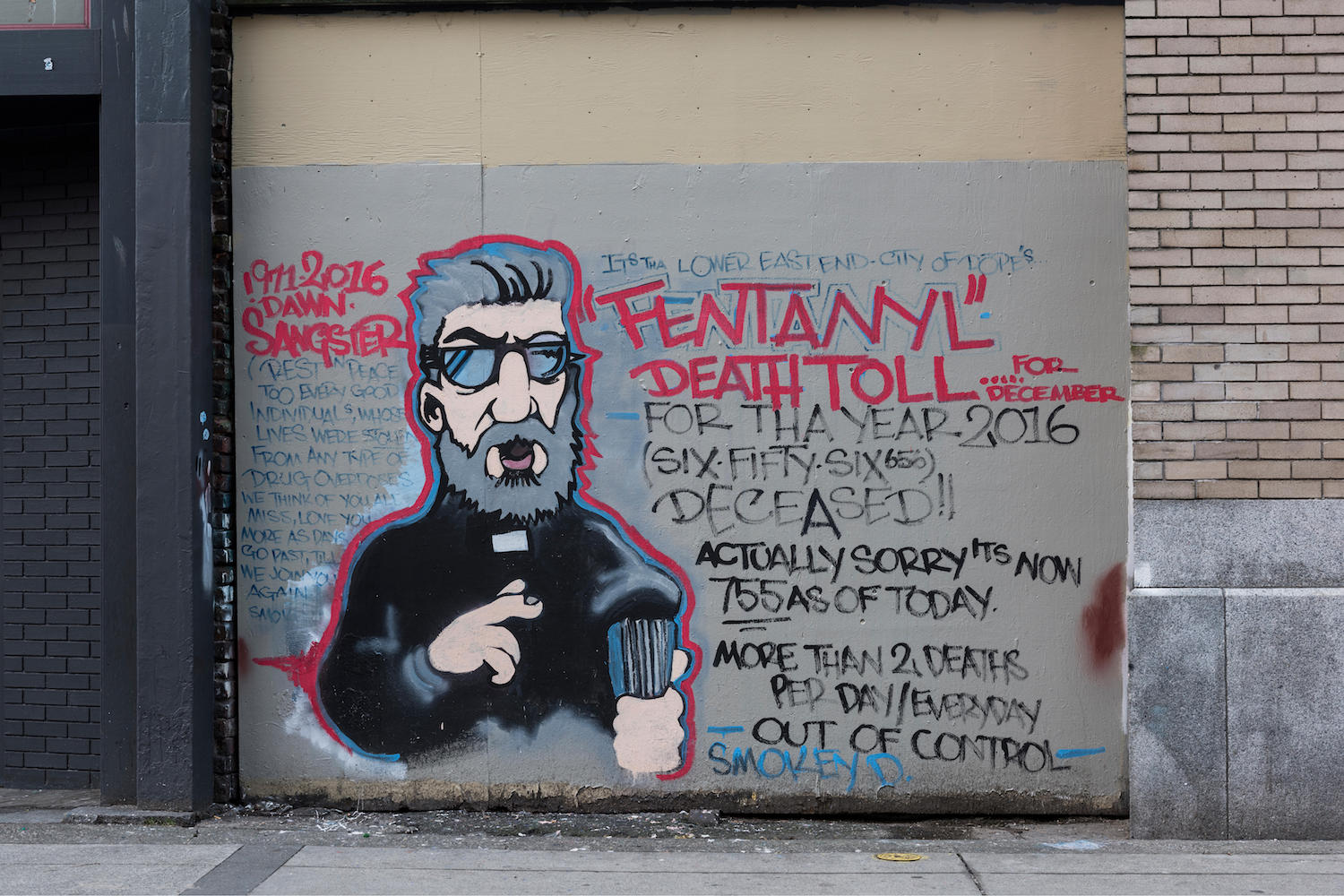

In 2017, a spike in fentanyl-related deaths in the north of England and a series of police raids on suppliers led many to believe the super potent opioid had finally found its way into Britain's narcotic food chain. It was only a matter of time, the thought went, before the devastation wreaked in parts of America and Canada—by heroin suppliers stretching out supplies with cheaper, more potent fentanyl—would start to be mirrored in the UK and Europe

On January 18, three dealers busted in April 2017 were jailed for a total of 43 years for selling 2,800 packages of fentanyl and 635g of pure carfentanil over the darknet from their storage unit in Leeds, West Yorkshire. Yet, in the nearly two years between their arrest and jailing, the expected US-style fentanyl explosion has so far failed to ignite. The drug has a growing presence in Europe, but that's still nowhere near the levels seen in north America.

In the US there were 29,000 deaths linked to synthetic opioids, mainly fentanyl, in 2017. Fentanyl usurped heroin in 2016 as the most lethal illegal substance in America. By contrast, in the UK in 2016, there were 58 fentanyl-related deaths, and 75 in 2017. The National Crime Agency (NCA), Britain's version of the FBI, told VICE that despite increased vigilance, it has not come across any significant fentanyl suppliers since 2017. Over the last 18 months, the NCA says, seizures of fentanyl at UK borders and on the streets have been "at very low levels."

A snapshot analysis of 460 heroin users at 14 treatment projects in the UK, carried out between December 2017 and May 2018 by Manchester University and drug agency CGL, found an average 3 percent of people tested positive for fentanyl. In the US, analysis of heroin users in treatment in Michigan carried out in 2015 and 2016 found 38 percent tested positive for fentanyl.

Fentanyl is "currently playing a small role in Europe's drug market," according to the EU's drug agency. Apart from an isolated and long-standing fentanyl problem in the Baltic state of Estonia, and clusters of deaths in Ukraine, Sweden, and Lithuania, the picture across the rest of Europe—and, in fact, globally—is of fentanyl as a much-feared, but as yet rarely found drug. There were 738 seizures of fentanyl in Europe in 2016, compared to 40,000 seizures of heroin.

In its 2018 World Drug Report, the UN's Office on Drugs and Crime reported: "Outside North America, with the exception of Estonia, where fentanyl has dominated the use of opioids for 15 years, the impact of fentanyl and its analogues is relatively low."

As the US desperately seeks an answer to its drug death vortex, and the rest of the world looks on in dread, the question has to be asked: Why are businesses that supply heroin to some of the world's most lucrative markets—such as the UK—so far refusing to adopt the callous, but highly economical, US fentanyl business model of mixing fentanyl into street heroin deals to maximize profits, even if it means killing off some of their valued customers?

Or, to put it another way: Why has this happened in north America and almost nowhere else?

A perfect storm of conditions over the last decade led to the current fentanyl epidemic in the US. It began with rising social deprivation and excessive opioid prescribing by doctors, leading to mounting addiction. Then came a crackdown on over-prescribing and a surge in demand for street heroin, which at the time happened to be poor quality and in short supply. In order to meet demand, heroin suppliers were boosted with the addition of fentanyl imported from China.

In a paper published this week in the International Journal of Drug Policy, Dan Ciccarone, a professor at the University of California in San Francisco, and an expert in heroin markets, says the fentanyl crisis came off the back of three successive waves of deadly opioid epidemics. "In the first wave, overdoses related to opioid pills started rising in the year 2000 and have steadily grown through 2016. The second wave saw overdose deaths due to heroin, which started increasing clearly in 2007, surpassing the number of deaths due to opioid pills in 2015. The third wave of mortality has arisen from fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, and other synthetic opioids of illicit supply, climbing slowly at first, but dramatically after 2013."

For the major heroin suppliers, fentanyl was economically an attractive option, being more profitable, cheaper, and easier to import, smuggle, and produce than heroin. It was no stranger to the black market in the US, a country with a history of non-medical use of fentanyl stretching back to the 1970s—and, with 6 million medical fentanyl prescriptions a year, many opportunities for illegal diversion.

The Mexican cartels, which had been experimenting with heroin substitutes such as fentanyl as far back as 2006, are responsible for the supply of most of the heroin sold on the streets of America. They found fentanyl easy to get hold of, mainly by importing it from China, but also producing it in their own labs. The potent hidden mixer helped shore-up unstable heroin supplies and was also easily mixed into the light-colored "white" Mexican heroin increasingly dominating markets in the Northeast and Midwest. The downside, as soon became apparent, was that its high potency meant it started killing many more people than the heroin it was rapidly replacing.

It is this factor that represents such a dramatic departure from normal "drug business." On a historic scale, US heroin suppliers have chosen to ignore one of the golden rules of drug selling: Don't kill your customer. There is a growing consensus that fentanyl-laced products sold as "heroin" are produced purely for economic reasons by suppliers, rather than something demanded by heroin users, who prefer the real deal. But what was it that made them take on the risk of losing so much of their customer base, a number approaching 30,000 people during 2017?

"The only reasonable answer is that the customer base in America is larger than we acknowledge, and the 'loss' is not acutely felt by the crass business leaders," says Ciccarone. "The other hypothesis is that there is no business leader: that it's the Wild West in America and no one is in charge. Perhaps a sub-cartel faction has taken control of a piece of America and is promoting fentanyl on its turf. Even so, it's a bold and risky move with deadly consequences."

Tino Fuentes, a drug harm reduction consultant working in New York, says the fentanyl business model is proving so successful for the suppliers that many heroin deals he tests in the city have no heroin at all. He says heroin could, ridiculously, soon be a "VIP drug" in the US because its replacement is so cheap and ubiquitous. Fuentes says a kilo of heroin costs between $30,000 to $50,000 and will yield a profit of $250,000, while a kilo of fentanyl costs $12,000 but can generate $1.3 million profit. "We have dealers now that don't really care much about the customers," he adds. "They're not trying to kill them, but while they try by trial and error to perfect the fentanyl mix, they don't care if people die in the process. It's totally fucked up."

WATCH: Fentanyl – The Drug Deadlier Than Heroin

So what's stopping the European heroin suppliers following suit, and could this offer a solution to the massacre taking place in the US?

It's an obvious point to make, but what booms in the American drugs market does not necessarily translate over to Europe. Methamphetamine, for example, is a huge drug in the US, yet a niche pursuit in most of Europe, particularly in the UK. Neither has Europe experienced the perfect storm of unfettered opiate prescribing, severe deprivation, and patchy heroin supply that America has.

Apart from its better management of prescription drugs, perhaps Europe's unsuspecting savior from fentanyl is its historical nemesis, Afghanistan, a country British troops have tried and failed to subdue three times over the last 200 years. Last year, 263,000 soccer fields worth of opium poppies were cultivated by a narco-state that produces 90 percent of the planet's illegal heroin, despite successive attempts by foreign invading armies and the Taliban to cripple its lifeblood crop.

As a result, unlike in the US, regional heroin distributors in Europe have now had a stable supply of high purity, low-cost heroin for nine years running. They have less of a desire to seek heroin alternatives, such as fentanyl because Afghanistan is the vast opium farm that keeps on giving. Average street-level purity in the UK hovers around the 40 percent mark, and a wholesale kilo comes in at around $25,000. In the US, street purity averages 33 percent and the wholesale price per kilo is almost double that of the UK, at around $50,000.

It is also getting easier, not harder, to smuggle in heroin from Afghanistan. Heroin coming into the UK is now less likely to be interdicted than it ever was, with the number of heroin seizures at the UK border down to a record low in 2018, despite rising purity and falling prices—indicating a healthy supply to the country. Unlike the Mexican white heroin that has acted as the major carrier for fentanyl in the US, Afghani heroin is brown. Like the Mexican "black tar" heroin distributed west of the Mississippi, Afghan brown is harder to mix with fentanyl, a white powder.

For Europe's dealers, fentanyl is currently not tempting enough. "If there is a good supply of readily available, cheap heroin, why switch to something that is more problematic? Why would you switch from an iPhone to another phone? You would need to have a reason to switch, you would need a better product," says Jonathan Cole, a professor at the UK's University of Liverpool with expertise in drugs markets. "If the heroin market is working really well for you, what is the value of adding fentanyl if you are making a good profit without killing your customers?"

When asked about fentanyl, one off-street heroin trader in Liverpool who does home deliveries, said he knows of no dealers in the city who would purposefully add it to their product: "Our heroin is good enough without fentanyl, and we don't want to kill any of our established customer base, or we would soon be selling to those dickheads in the street."

Those tasked with hunting down Britain’s organized dealing gangs say they are not complacent, but have seen little evidence of fentanyl gaining much traction among major sellers in the UK. "We have seen high levels of production of heroin in Afghanistan, and heroin at high purity levels here, so maybe that’s why dealers are not adulterating their product with fentanyl," says Vince O’Brien, head of drugs operations at the NCA. He says other factors could be that since the NCA took out drug web market Alpha Bay in 2017, fentanyl is less easy to buy online, with many online drug markets now refusing to host fentanyl sellers. Perhaps, says O’Brien, the media coverage of America’s fentanyl disaster has acted as a bad omen for those running Europe’s heroin crews: "Fentanyl is so toxic, and maybe gangs are scared of making themselves ill, of getting big sentences or of killing off their customers."

All this could change, for example, if some kind of disaster hit Afghanistan’s opium machine, such as a major poppy blight or an enforced Taliban anti-opium edict, similar to that which hit supplies in 2000. The obvious conclusion for America, as fentanyl looks set to completely take over heroin as the number one street opioid fix, is to fight fire with fire.

Rather than wasting millions of dollars on building a wall that will not keep fentanyl out, or attempting to stem the stream of fentanyl through the internet and postal system, a rival product could offer a route out of the deadly corner in which America has found itself. Whether this opiate product is handed out by drug treatment services to users wanting to get off heroin, or by entrepreneurial criminals able to undercut the fentanyl business model using a safer opioid, it can only reduce the body count.

Either way, what is looking more inevitable the longer prohibition holds out is that the global illegal drug trade is moving inexorably away from plant-based substances trafficked via traditional trading routes, and onto a more high-tech platform: synthetic highs made in underground labs, ordered online, and trafficked under cover of a million brown packages—many times more lethal than the natural highs they will soon replace.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Max Daly on Twitter.

from VICE http://bit.ly/2RJ652B

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment