This story appears in VICE Magazine's Truth and Lies Issue. Click HERE to subscribe.

Growing up in foster care, Isaac Demerest learned to keep small pieces of flint and steel in his shoelaces and a perfume vial filled with gunpowder and Vaseline in his pocket to use as a fire starter. Dental floss—what he calls an “easy fix-it thing”—was always on hand. Because he was obsessed with the Sherlock Holmes books, he practiced breaking locks in school and wherever he was staying. The resourcefulness he demonstrated as a kid wasn’t exactly a hobby, but rather a necessary survival tactic as a ward of Washington State.

“In all honesty, everything I owned back then fit in a black garbage bag,” he told me over the phone in January. “When I started driving, everything fit in my car. I became really good at keeping the bare essentials, and at wilderness survival. As I got older, the sense of preparedness and desire to be prepared just kind of continued on from that.”

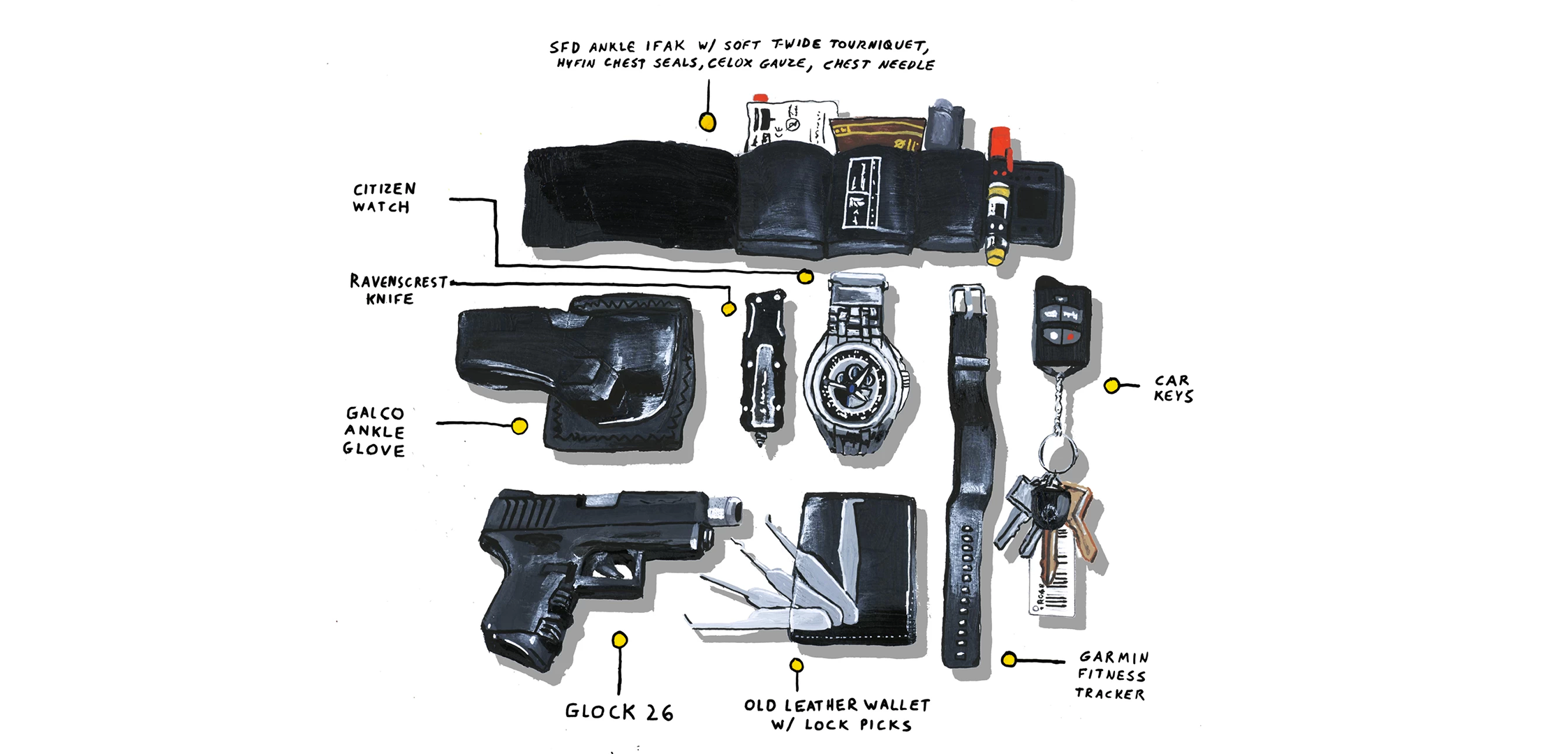

Now 42, Demerest works as a money manager in Toledo, Ohio, where he finds some childhood habits hard to break. He carries a survival pack’s worth of stuff underneath his suit every day, including a trauma kit he keeps attached to his ankle. His pockets are full of flashlights and pocketknives. Though he describes himself as not interested in fashion, being a professional investor affords him a certain amount of discretionary income, some of which he is proud to have spent on a Citizen Eco-Drive solar-powered watch, which he matter-of-factly describes as “visible, so it does have to be aesthetically pleasing.” And he enjoys sharing both his practical and fashionable accessories online as part of a community that does just that. He recently published a photo of his spread on a subreddit called /r/EDC—short for “everyday carry”—along with his age and profession, as is customary. One incredulous response was probably to be expected: “You carry lock picks every day? As a financial planner?”

I could sort of relate to the guy. After all, I spent the tail end of my college years at the University of Florida living with a couple of left-leaning good ol’ boy twins from North Florida and our other friend who was studying civil engineering. Everyone was really into what I referred to in my head as “Southern man stuff.” We had a smoker in the backyard; there was an untold amount of weaponry squirreled away in cabinets and closets; and tools and plywood covered the porch. I spent enough time immersed in that environment that I became interested in the objects I was surrounded by as well. We were all at least familiar with a blog called Everyday Carry—a simple site founded roughly a decade ago that showed images of what people would carry in their pockets on a daily basis. Part style guide and part field manual, it was something we mostly made fun of. One time we got drunk and took pictures of some of the most ridiculous things we could find in our house (like axes), all done in the EDC style, the items organized together in an aesthetically pleasing way, shot from above.

Regardless of how seriously we took the site, as we began to acquire disposable income, our interest in the lifestyle it championed (or at least in the products it advertised) persisted well beyond graduation. Meanwhile, our purchasing patterns bifurcated along two distinct paths. The twins stayed in the small-town South, where they continued to buy tools that had at least some practical use. My other friend moved to Miami, and I moved to New York, where it was a little less obvious what we were supposed to do with the items we had learned to covet and now finally had the ability to buy on a whim.

As Everyday Carry’s popularity soared, its growing audience seemed to fall along similar lines. If you check the site out now, you’ll still see posts from cops and military personnel, whose EDCs consist of firearms and other tools of the trade. But an increasing number of participants seem to be civilians who post pocket dumps of European heritage-brand knives, leather-bound passports, and astronaut-grade ballpoint pens. Indeed, the concept of EDC has now reached such a level of ubiquity among the latter cohort that Men’s Health, Men’s Journal, and GQ make gift guides that use the term in their headlines. EDC is now a distinct product category, like winter wear, that’s inescapable for anyone with a passing interest in men’s fashion.

Even though I mocked the concept of EDC just a few years ago, I’m now fully enslaved by this admittedly powerful branding. In a particular fit of mania two years ago, I bought a Leatherman multi-tool that I planned to carry in my pocket at all times. There were a couple of problems off the bat. First off, anyone who’s ever worn women’s jeans knows that their pockets are not designed to fit anything more substantial than like, two nickels and a paperclip. But more depressingly, I realized after a couple of weeks that I was only using it to open Amazon Prime boxes. It now sits in a drawer, though I regularly fight the urge to acquire more knives that are advertised to me with a disturbing degree of regularity on my Facebook and Instagram feeds. “For better or for worse, the most common use of my pocketknife is opening packages,” Demerest told me, suggesting that I wasn’t alone.

I’ll be the first person to admit that I’m easily manipulated by advertising; I got emotional about that recent Gillette commercial calling out toxic masculinity, despite my intellectual awareness that it was corny and virtue signaling and engineered in a lab to make me buy razors. But my specific experience with regard to EDC raises another question about what people are trying to telegraph through their consumer choices: Why are so many American office workers obsessed with artisanal pocketknives? What seemed more likely: that Danny (a consultant from Central Florida whose post I recently saw on EDC) never left the house without at least one of four knives and a knife sharpener? Or that he desperately wanted to be seen as someone who always needed to have those objects (as well as a titanium pry bar, a set of pliers, and something called a “survival whistle”) at hand?

The concept of Everyday Carry would have been beyond absurd to the men who in many ways experienced the predecessor of the kind of lifestyle it seems to be channeling, like those who lived and worked in lumber camps around the turn of the 20th century, who carried everything they owned on them by necessity. As outlined in a paper by Adam Tomczik that came out around the same time Everyday Carry launched, called “‘He-Men Could Talk to He-Men in He-Men Language’: Lumberjack Work Culture in Maine and Minnesota, 1840–1940,” workers sometimes labored in temperatures well below zero, but didn’t pull their caps down over their ears or wear mittens out of masculine pride. And while modern EDC nerds pore over the specs of titanium fidget spinners, these were guys who entertained themselves by playing a game called “hot ass” that revolved around slapping each other with frozen fish. These were not the beard-oil-wearing hipsters of the mid aughts: Travelers who cataloged the living conditions would lament how much the cabins smelled like farts.

These logging camps in the Midwest and Northeast managed to resist workplace modernization well into the 1930s. Long after other companies had installed human resources departments, Tomczik notes that the success of a logging camp’s management continued to be measured by how well individuals could get along with their men—and in some instances, whether they could ward off physical attacks from their subordinates.

Pictures taken by itinerant photographers tell the story of how lumberjacks worked in open defiance of the societal shift toward efficiency and more sterile working conditions. These images, some of which are reproduced in “He-Men,” show the men sitting atop the wood they had cut and bound. The piles aren’t the log loads that were typical of the time; instead, the images portray roughnecks showing off atop monster creations that are roughly 15 times bigger. This was a tribe who took pride in dangerous work and in their identity as outsiders. Paul Bunyan, a figure in early oral histories and legends, took on national fame after appearing in marketing pamphlets from the Red River Lumber Company. Bunyan’s endurance as a folk figure suggests that Americans took pride in the idea of dangerous work, too, whether or not they had any connection to timber production itself.

A number of factors that changed the logging industry contributed to the end of lumberjack culture—or at least that iteration of it. Consolidation of logging operations, decline in the logging industry during the Depression, the introduction of foresters to reseed and protect forests so production could continue, and the rise of technological advancements in logging that changed how the job was done—all these things remade logging into an industry more accessible to the modern era. And as Tomczik writes, the advent of the personal automobile killed the lifestyle of residential logging camps. No one was going to stick around for a game of “hot ass” around the campfire when they could just go home and be with their wives after work.

Fast-forward to the 2008 financial crash, and our society began to witness a kind of return to the lumberjack way of life—at least in terms of appearances. Among certain populations, there began to be more men who epitomized a certain aesthetic—plaid shirts, beards, a rough-and-tumble attitude. It was a website called GearJunkie that gave these phenomena a name, in 2014: “He looks like a man of the woods, but works at [a consulting group], programming for a healthy salary and benefits. His backpack carries a MacBook Air, but looks like it should carry a lumberjack’s axe. He is the Lumbersexual.” The group was immediately marketed to.

Some attribute the rise of lumbersexuality to the recession, which disproportionately affected men, and may have contributed to some men losing their identity as providers. As Willa Brown wrote in the Atlantic, they sought a psychological escape from their increasing irrelevance by playing dress up. I’d take that argument a step further and say that this phenomenon of buying handcrafted, artisanal products was directly related to the sense among the millennials who were coming of age at the time that the institutions trusted with keeping society afloat were flimsy at best and that globalization was making them more unstable by the minute. As the world fell apart around them, people wanted things with a certain amount of physical heft and traceable heritage. “We wanted to invest in things that were real,” agreed Tom Handley, a professor of menswear at the Fashion Institute of Technology. Hence the rise of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, as a haven for “makers” in the early aughts and the craftsmanship championed by lumberjacks in the early 20th century seeing a popular comeback. “Even if it was a hatchet or an ax, they were going to hang it over their fireplaces and think ‘Damn, that looks good,’” he says. “I do think guys wanted to have an awesome thing that no one else had.”

This phenomenon of buying handcrafted, artisanal products was directly related to the sense among the millennials who were coming of age at the time that the institutions trusted with keeping society afloat were flimsy at best and that globalization was making them more unstable by the minute. As the world fell apart around them, people wanted things with a certain amount of physical heft and traceable heritage.

Now, it strikes me that the men enamored with the concept of EDC are going through something similar, perhaps for reasons that also explain why Deadliest Catch is one of the top original cable shows on TV. They may gear less toward the lumberjack aesthetic and more toward occupations or movements that call for being prepared and ready at all times. Perhaps EDC’s beginnings as a place for off-duty cops and other first responders to post about their gear gives us some insight into the aesthetic current EDCers are trying to emulate; it may be trying to sell the concept of authenticity, this time with the added component of gadget fixation, to convince guys to buy things they might not need so they can feel like they, too, are prepared for the end of the world (or just a sticky situation). In the era of a mass reconsideration—and often villainization—of men, those who carry knives and titanium pry bars can feel as if they could be the masculine heroes of their own action movies, should the need arise.

It may have been no coincidence, then, that the idea for EDC as a big business came in 2008, when Bernard Capulong was a college student at University of California, Irvine. He was interested in streetwear, and back then, it was trendy to put knives, flashlights, and brass knuckles in the pockets of your raw-denim jeans so that they would leave an imprint once you finally gave them their first wash. Rather than spend a fortune on the Supreme-branded flashlight intended for this purpose like other people he knew were doing, Capulong decided to find a generic alternative online. The number of options—as well as the amount of information about each of them—was overwhelming.

“I started researching flashlights, and it turns out there’s a whole subculture of flashlight nerds,” he said over lunch this past September in Williamsburg, where he lives with a friend he met a decade ago on a fashion forum about jeans. “They had their own online discussion forums. And that’s when I discovered that there was literally an online community for each tool.”

After becoming immersed in a handful of those communities, Capulong registered a Tumblr in 2009 where he blogged about all the tools in one place, and as it grew in popularity over the course of a couple of years, he began asking people to send him the contents of their pockets every Saturday. He’d rate the submissions based on whether people’s EDCs “were sensible and practical for their needs, because EDC is a super individualized thing,” as well as if the knives people were carrying, for instance, were legal in their area.

“I definitely wasn’t a prepper or an off-duty cop; I was a college student,” Capulong said. “But I still had use for these things in my research lab or in my engineering club, in a way that was a bit more urban and not so much survivalist. That’s where I was coming from when I made my recommendations, and I think that resonated with a lot of people, especially on social media at the time because that’s more mainstream and accessible than, ‘You have to go to multitoolforum.org’ or whatever and read all these threads. No one was going to do that.”

Basically, he made a trove of rarefied knowledge accessible to fashion-oriented guys who weren’t willing to put in the work of learning about different light outputs, intensities, and beam patterns. What he didn’t know at the time was that this would end up bringing cops and soldiers to fashion as well. In starting his blog and taking EDC mainstream, Capulong inadvertently tapped into the fact that all these seemingly disparate demographics were desperate to connect over the desire to romanticize rugged survivalism.

As he was preparing for med school, he was approached by an entrepreneur named Jonathan Smyth, who pitched turning the Tumblr into a full-fledged business. After a seed investment of about $50,000, the site has grown each year and now, according to them, reaches about a million people per month. That audience then generates millions in revenue for the sponsored brands they have on the site, and they get a commission off that. (Capulong has put his plan of becoming a doctor permanently on the back burner.) More anecdotally, Capulong can tell that the culture has changed to be more permissive of random men hoarding knives. When he was in college, people eyed him with suspicion for carrying a bevy of weapons; five years later those same people started asking him, “What’s a cool knife I can buy?”

Around 65 percent of the traffic on EverydayCarry.com is from the US, and unsurprisingly, about 90 percent of it is from men, according to Smyth, who is the site’s chief operating officer. He says that Everyday Carry makes about half its revenue from affiliate links, and that the other half comes from straight advertising. There’s a team of about ten people who work on EDC and a global network of paid contributors who write for the blog. They do collaborations with other companies, like gift guides for TechCrunch, and Capulong occasionally guest blogs for sites like GQ.com to further proselytize (and monetize) the concept. Some of the original EDC people also started selling their own line of products in January called Hammerstone Goods.

“There’s definitely still that group [of cops and army guys], but there are now also dudes with disposable income who want to feel like they’re rugged or whatever,” Capulong said. “There’s a little bit of a totemic aspect, where if you carry a pocketknife, it’s as if you’ve assumed the license to be adventurous and manly. You’re not necessarily going to use it, but it’s cool to have.”

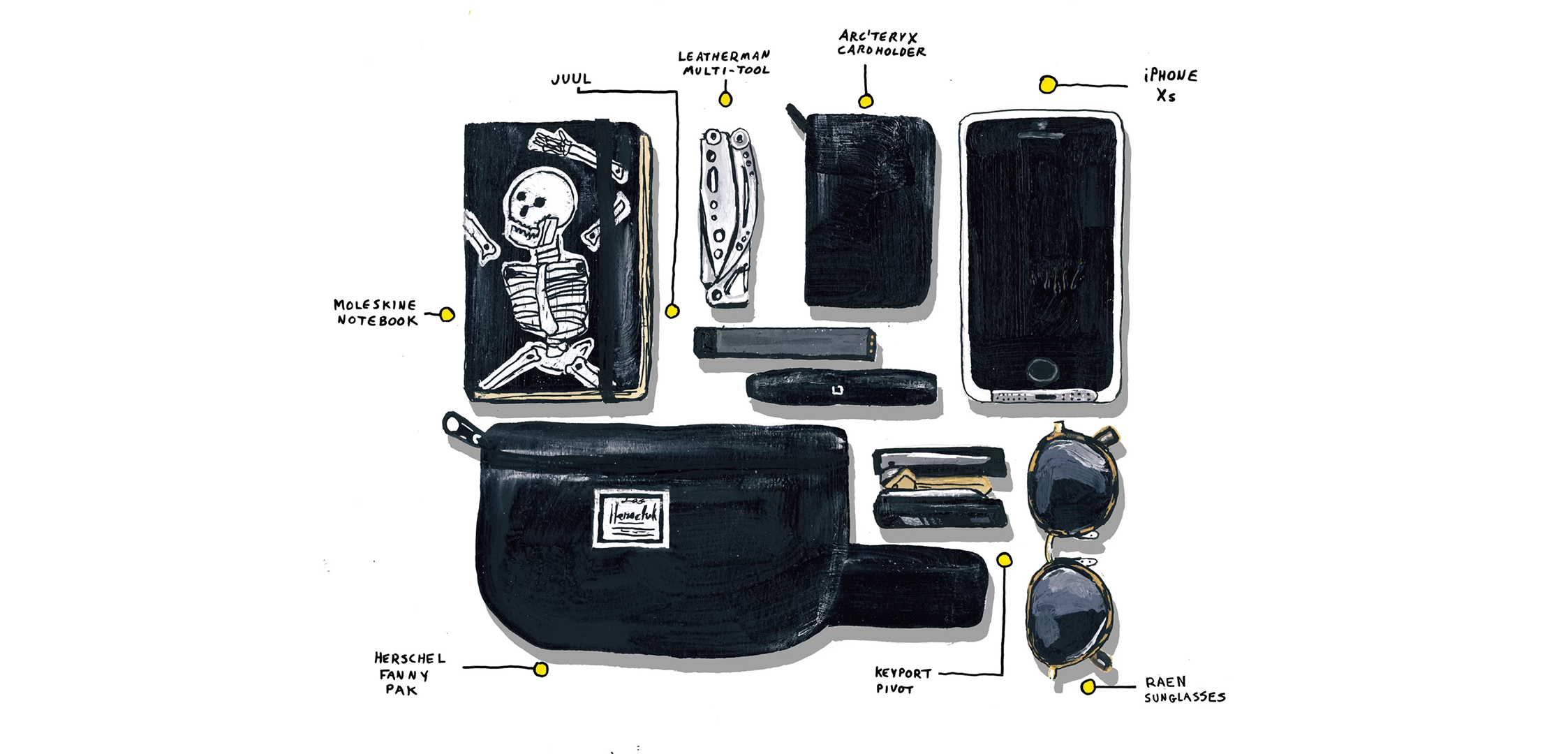

I thought that meeting with Capulong would demystify EDC for me. But my interest only intensified after our lunch. I was suddenly obsessed, spending hours scouring New York City for the exact wallet he’d flashed me during our meeting, when I asked to see his own pocket dump. I wrote to KeyPort, a company that makes a foldable contraption that stores people’s keys without clanking or clutter, and was sent a model to try out. I upgraded my five-year-old iPhone and chose a minimalist case that I thought would be photogenic. As I mentioned before, my only prior experience in taking a top-down gear photo was in jest, but I soon craved the experience of taking and posting another one in earnest after those upgrades.

“It may not sound scintillating in principle, but in practice it’s addictive,” wrote TIME when it included EDC as one of 2011’s best blogs. “And thinking about how these people’s possessions hint at their personalities will get you thinking about how your accoutrements reflect your own.”

After getting in touch with a handful of other folks who network around EDC, I gathered that my initial hypothesis about there being two personality types there was correct. There were people like Capulong who liked knives even though they only used them to open boxes—and people who erred more on the survivalist side. However, no one I spoke to was a lumberjack, exactly. In fact—and oddly enough—two of them were backwoods pastors who cracked up when I asked them if they cared about fashion, but they were both at a loss to articulate why they wouldn’t leave the house without a fixed blade and a mag light. Though Demerest said he recently used his lock picks to help some friends who lost their keys, the biggest advantage the EDC hobby tends to bring these guys is that their wives now know what to get them for Christmas. When pressed, he admitted the act of heroism was an anomaly. “I’m gonna be honest,” the financial planner told me, “I don’t use this stuff much. My most common tool is a bottle opener.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Allie Conti on Twitter.

from VICE https://ift.tt/2Uufb5G

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment