This article originally appeared on VICE UK.

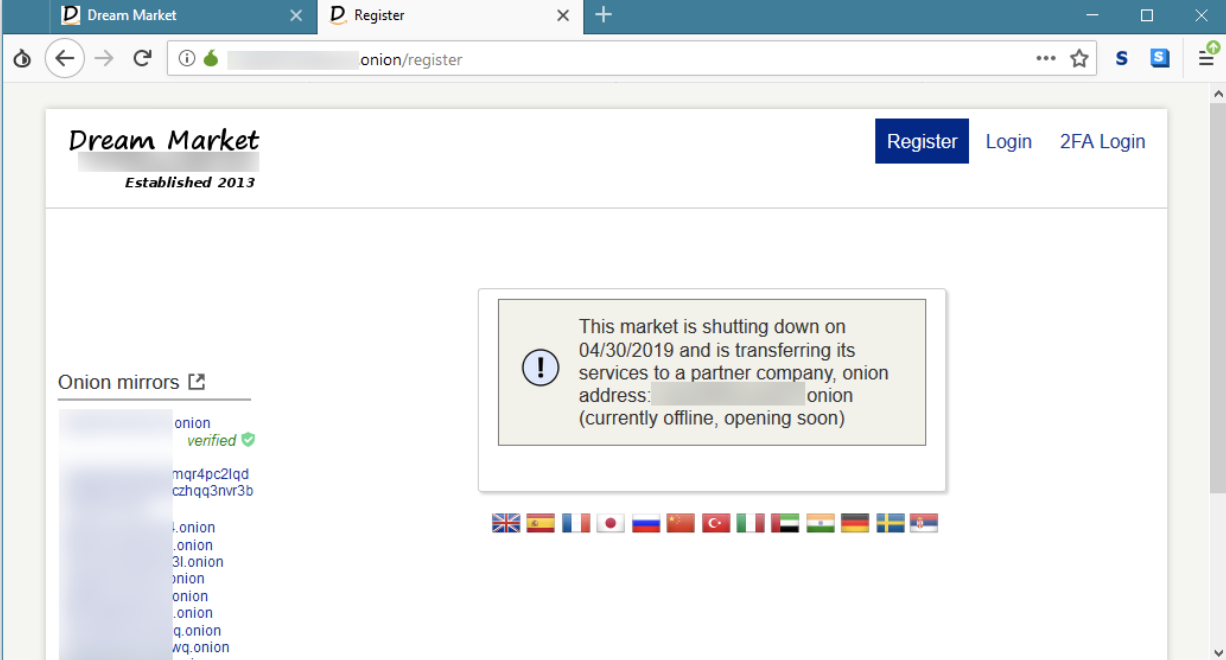

Just over two weeks ago, on March 26, hundreds of thousands of people worldwide logged on to the dark net market site, Dream, and found the following message:

All buying and selling on Dream (the largest, longest-running, and most-used dark net market) has been halted. Most vendors and users have, however, been able to access the site and withdraw funds. But when it shuts down for good at the end of the month, it will mark the closure of hundreds of thousands of listings generating millions of dollars in trade each week.

The move has left customers, observers, and dealers wondering whether Dream’s closure could mark a shift in the way the dark web is used to buy and sell drugs. There is talk of a mysterious new and yet-to-open partner site, but many are wondering whether this could be a honeypot devised by the authorities.

A Dream forum admin, ‘Hugbunter,’ has claimed on a Reddit-like dark web forum called Dread that Dream Market has been held ransom for $400,000 by a hacker, but has refused to pay. He says the attacker is exploiting a browser quirk that makes an extended attack of this kind simple and cheap.

Dream’s partial closure did not come out of the blue. It had followed a sustained attack by hackers on the site, rendering it inaccessible for most of the previous two months. Known as a Distributed Denial of Service (DDOS) attack, it involved a technical assault by malicious hackers—or government agents—who bombard its front pages with millions of bogus users, slowing the service down to a digital traffic jam. These attacks are carried out in order to taint a site’s reputation and render it unusable.

The FBI pulled a similar trick in 2013 on the original Silk Road before cloning, controlling, and monitoring its server traffic. That takedown and a lengthy and corrupt investigation resulted in the life imprisonment of Silk Road’s owner, Ross Ulbricht.

Seasoned dark web watchers know any kind of downtime or strange activity on a market usually presages a bust. But in this case, there has been no crowing FBI splash page claiming the site-owner’s scalp, as happened with the Silk Road. The site has not been shut down immediately but is being wound down. If cyber police have seized the site, they seem in no rush to fully close it. The question is: What is really going on?

Normally, when site admins make announcements such as the Dream closure notice, their messages are verified by using a cryptographic ‘signature’ feature using PGP encryption software. This proves that the message was written by its claimed author. The Dream closure notice has not been signed by anyone—which is an uncharacteristic oversight suggesting the hand of the law.

This has led many online drug traders to conclude that this partial closure could well be a police trap. Perhaps the original Dream site is now under the control of the FBI. Maybe the police have seized Dream’s server and are tracking all users and their bitcoins in and out of the site. For all its supposed anonymity, every bitcoin transaction ever carried out is recorded in a public, indelible, unchangeable log (the blockchain). There is even speculation that police could have cracked Tor, the anonymizing browser used to surf the dark web.

One theory popular among twitchy forum posters right now is that the DEA or FBI have been running Dream for months, looking for slipups, monitoring large in and outflows of bitcoin, and are using technology to unmask users, buyers, and operators.

In 2017, a multinational police operation, Operation Bayonet 2.0, seized AlphaBay, a vast market ten times the size of the Silk Road. Owner Alexandre Cazes was captured and days later reportedly died by suicide while in police custody in Thailand, and hundreds of thousands of users fled to a new market, Hansa. But Dutch cops were lying in wait to ambush them. They'd secretly been running Hansa for a few weeks, harvesting user data and hijacking the site’s inbuilt encryption system. This meant anyone using Hansa’s encryption system to communicate with their dealer—sending them their home addresses for postal delivery of drugs—were actually signing a confession to the Dutch National High Tech Crime Unit.

“After so many users got stung in the Hansa honeypot operation, there is a similar sense of dread about Dream's claim to be re-opening on a new site,” says Patrick Shortis, a criminology researcher at Manchester University who is a dark net market and cryptocurrency expert. “Users are worried that either the current market or its replacement are compromised by law enforcement.”

Dream has been run for six years by a tight-lipped admin known only as ‘Speedsteppers.’ Unlike Ulbricht, a politicized tech-savant, Speedsteppers is no ranting libertarian. Instead, they're a smart, tech-literate, media-savvy digital drug kingpin. If loose lips sink ships, Speedsteppers has captained this outlaw fleet with silent aplomb. His or her ideological motivations remain a mystery, beyond the acquisition of bitcoin, gained through a percentage commission charged on each sale.

There can be no doubt that the FBI and DEA have been trying to take Dream down for years. Shortis agrees that the closure of Dream smells fishy. “Cryptomarkets don't usually wind down,” he says. “Usually, the admins close the site and abscond with user funds left in the centralized escrow system—a move known as an 'exit-scam' he says. “This is by far the more common way of a market closing. While not unprecedented, the cryptomarket Agora was wound down by its admins in 2015, this is definitely outside of the norm.

“What makes it even more unusual is the fact that Dream is claiming it will open again on a new URL,” says Shortis. “If Dream were closing because the staff want to retire, then that would make sense, but closing to reopen under a new name likely means losing the thousands of users that the site has accumulated over the years and starting again from scratch.”

The authorities key aim against dark net markets is to destroy users’ trust. The theory goers that disruption makes markets look weak, and puts people off from using them. "The closure of major marketplaces in the past has caused disruption, the ecosystem takes time to recover and there is an erosion of user trust,” says Teodora Groshkova, a dark net expert at the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. “The identification and targeting of major vendors (in addition to market administrators) is necessary to prevent simply displacing activity from one marketplace to another.”

So, is this the end of dark net markets as a means by which to buy drugs conveniently, without the risk of you are being watched by the law? No, says Shortis. “The community is resilient and tech-literate and collaborative, and has been through this many times before. Trade may drop for a short time during these kinds of events, but it recuperates quickly. I don't see why this would be different.”

Time will tell. The news of the Dream closure coincided to the day with news from the FBI of a string of dark net drug arrests in Operation SaboTor. It resulted in 61 arrests and the shutdown of 50 dark web accounts, and as yet we do not know if these were connected to Dream. Even so, the cat and mouse game between online drug traders and the police is far from over. There are still many other dark net markets operating, and single-vendor sites, too, plus new app-based vending across Wickr, Telegram, Instagram, and Facebook, as well as standard mobile-phone delivery services.

As it is with the old school street drug trade, closing dark net markets does very little to reduce demand. If anything, a flurry of activity is seen on forums as users try to contact their favorite vendors offline and elsewhere. Buying drugs by post offers too many advantages to drug users for them to simply stop.

One newish market, Wall Street, has been steadily adding 100,000 users every day for the last week, and now has over one million registered customers. User feedback threads below drug offerings on Wall Street show that for now, it’s business as usual. The site has been running for a few years, and dozens of the biggest vendors—some from the original Silk Road—have set up shop there. That site, too, may be a trap, or it may not.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Mike Power on Twitter.

from VICE http://bit.ly/2Iq1XDV

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment