When you first visit it as Young Link in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Hyrule Castle Town is a jovial and bustling marketplace. People are dancing, children are playing with each other, and music fills the air. It is so, so full of life.

But when you return to it as an adult, wielding the only weapon said to be able to defeat the tyrannical Ganondorf, it is ruined. "Ganon’s Castle" looms ominously in the distance. There are no shops, let alone shopkeepers. The entire town lies still under maroon light, except for the zombified ReDeads, undead mockeries of the people we once knew. There are no more pets to chase around, archery targets to snipe, or Bombchus to let loose. All that’s left is decaying flesh, hunger, and the screams. More terrifying still is the realization that in attempting to destroy the King of Evil in the past, we’ve actualized his victory in the future.

As a series that is marketed towards and enjoyed by younger players, Nintendo could understandably choose to exclude unsettling material from The Legend of Zelda. Instead, the franchise has long experimented with horror elements, deploying them judiciously to peel back the facade of its cheerful fantasy. Nintendo’s upcoming sequel to Breath of the Wild, revealed in a teaser trailer at E3 two weeks ago, continues in this tradition, leaving an indelibly creepy mark.

Zelda and Link appear to be exploring the caverns underneath Hyrule Castle. It is dark. Too dark for our heroes to traverse safely without torches and a ox-drawn caravan of supplies. They come upon an altar with a desiccating corpse contorted in pained expression, barely restrained by a bright blue force, all while it secretes a miasma that threatens to leak outside the unlit chamber.

Breath of the Wild’s vision of horror was already striking in fashioning the Calamity Ganon as a world-corrupting force rather than a single person or entity. No matter where you wandered in Hyrule, you were only so far away from the encroaching evil emanating from Hyrule Castle. You could head right to its front doorstep after completing the intro and face down the final boss, circumstance and formality be damned. Wisps of lore and scattered ruins hinted at the exact capabilities of the existential threat, but at the end of all things, you felt like nothing could fully encompass its magnitude.The ever-present menace woven into Breath of the Wild’s Hyrule—itself a pastoral tapestry that’s equal parts wonder and mystery—made Calamity Ganon the most harrowing villain in Zelda history for me, and with climate change and the rise of global fascism, its presence feels more timely than ever in 2019.

Going by the Breath of the Wild sequel teaser, we might not have seen the last of its terror. Following the clues hidden in the trailer and connecting the dots from Breath of the Wild itself, the altar figure’s identity seems to be none other than Zelda’s perennial villain, Ganondorf.

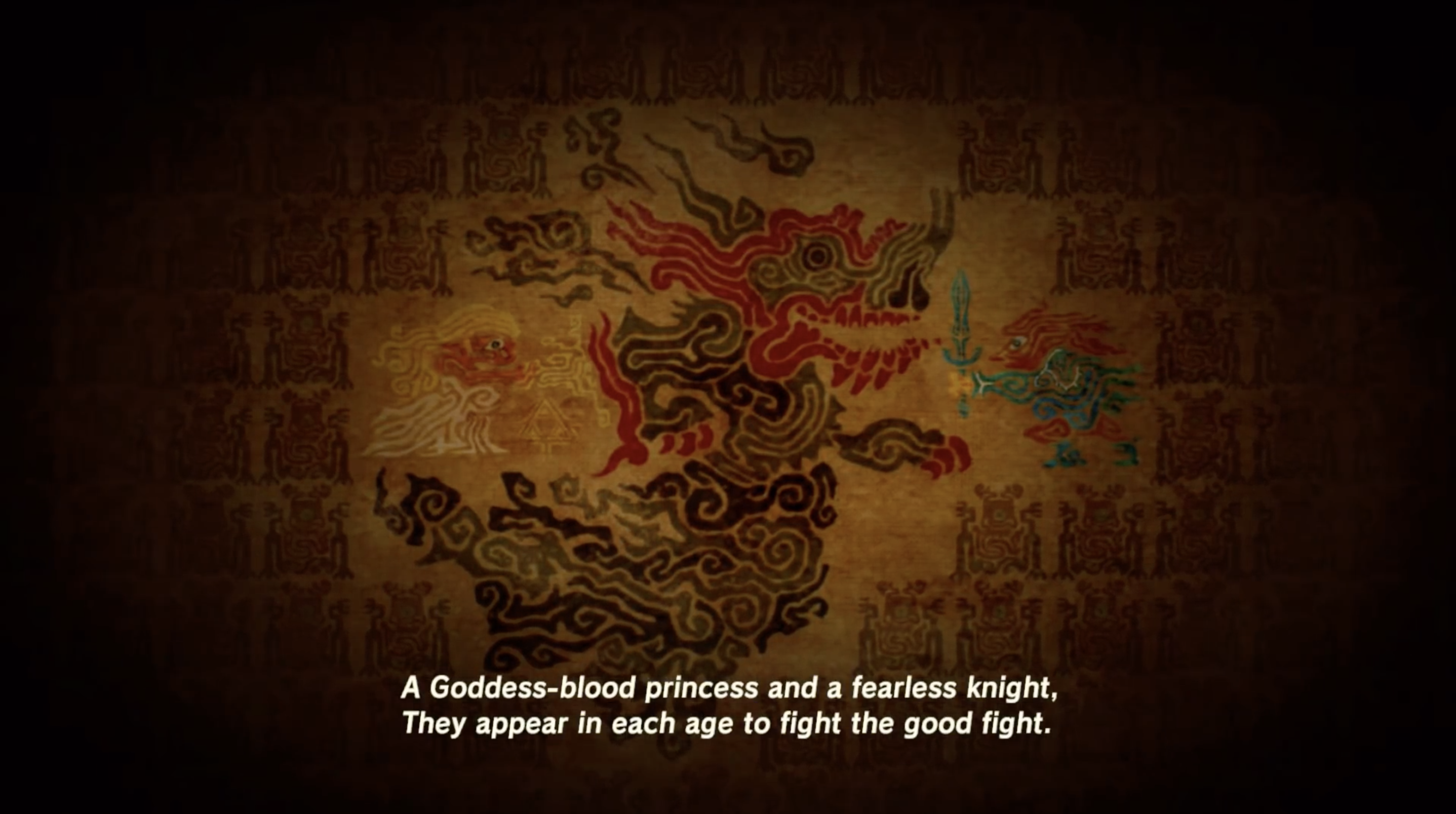

The miasma shown is similar to Calamity Ganon’s aura, and the placement of this corpse seems to coincide with a legend told to us by our friend Kass, the wandering Rito minstrel. In song, Kass recounts how 10,000 years prior to Breath of the Wild, Zelda, along with the combined forces of the Guardians, the Divine Beasts, and a single Chosen Knight, fought valiantly against Calamity Ganon. Curiously, the tapestry shown during Kass’ song displays the Chosen Knight as someone with a seemingly dark complexion and red hair. Sounds like a certain Gerudo Prince, no?

If this is Ganondorf, was he a willing participant or an unwitting victim? Did he knowingly sacrifice his life and body to contain the force of Calamity Ganon, or was the operation simply a clever gambit to trap him in a state of undeath, thereby nullifying the Demon King’s penchant for revival? The body sits at the very bedrock of Hyrule Castle, shaking the foundations of the land at the close of the teaser.

It is not a subtle image! Fans have jumped at the opportunity for a potential Ganondorf heroic turn. You, uh, owe it to yourself to check out some of the sumptuous art of this newly dubbed “Rehydrated Ganon.” Regardless of this providential corpse’s identity, it displays a material consequence of violence seldom felt in Zelda.

When we kill enemies in Zelda, we are so often treated to a cleansing flame that withers away their remains to reveal the newly pristine. Not so, here. This is a corpse and it casts a pall over the entire teaser. As the body shunts its face at us and its previously-hollow eyes ignite, we know that it must be heeded. When I first watched the trailer, I wrapped my arms around myself for security as I could not escape the feeling of mortal danger for our dear heroes.

As if the trailer’s scary atmosphere wasn’t enough, careful viewers have noticed that the force binding the corpse is similar to the blue spell energy used by the Twilight Princess’ Twili, a species of shadow beings. Creepy synths used in the trailer’s score also evoke the soundtrack of Twilight Princess, a sharp departure from Breath of the Wild’s wistful piano and strings. By making these connections, this sequel has solidified its place in a franchise eager to explore terror.

After all, breaking with genre convention isn’t new for Zelda, it’s been there from the beginning.

A History of Horror

When the bright and colorful world of Hyrule is compromised by terrors mundane and fantastic, it sticks with us. We’re shocked outside of our comfort zone and forced to confront uncomfortable topics. The first adult sequence in Ocarina of Time mentioned above wouldn’t hit nearly as hard in a more conventional “dark” or “mature” story. If we were mired in dour circumstances from the onset, we’d lose the turn from simple, childlike understanding to adult responsibilities and consequences being foisted on us. There’s an uncanny effect achieved by having disparate tones come into conflict. Instead of dimming the fantasy or defanging the terrors, the two are heightened.

In The Legend of Zelda for the NES, you can see a good example of Nintendo’s experimentation with horror in a classic enemy: the Wallmaster. Over the course of the game, players guide Link through various dungeons across Hyrule in a quest to stop Ganon, the Prince of Darkness, from plunging the realm into chaos. Inside those dungeons, players look for keys and utilize items like bombs to access new rooms and eventually fight a boss. Dungeon progression was fairly straightforward—a to b, b to c. That is, until the rule-breaking Wallmasters came along.

Unlike most enemies in the game, which spawned immediately upon Link entering a room, Wallmasters would covertly creep out of the walls. They weren’t a boss enemy and it didn’t matter how many hearts the player had left, if they caught you, you were sent back to the beginning of the dungeon. One false move meant that players’ hard-earned progress was lost, and this one simple design was enough to change how oppressive the space felt. What once felt direct and surmountable could actually be hiding something indefensible. By upending the power relationship of the player’s progression, Nintendo keenly tapped into a convention that horror games to this day continue to utilize: Set up reliable and safe gameplay expectations, then subvert them. Plus, compared with the rest of the game’s storybook enemies, a human-sized hand hiding in walls just hit differently.

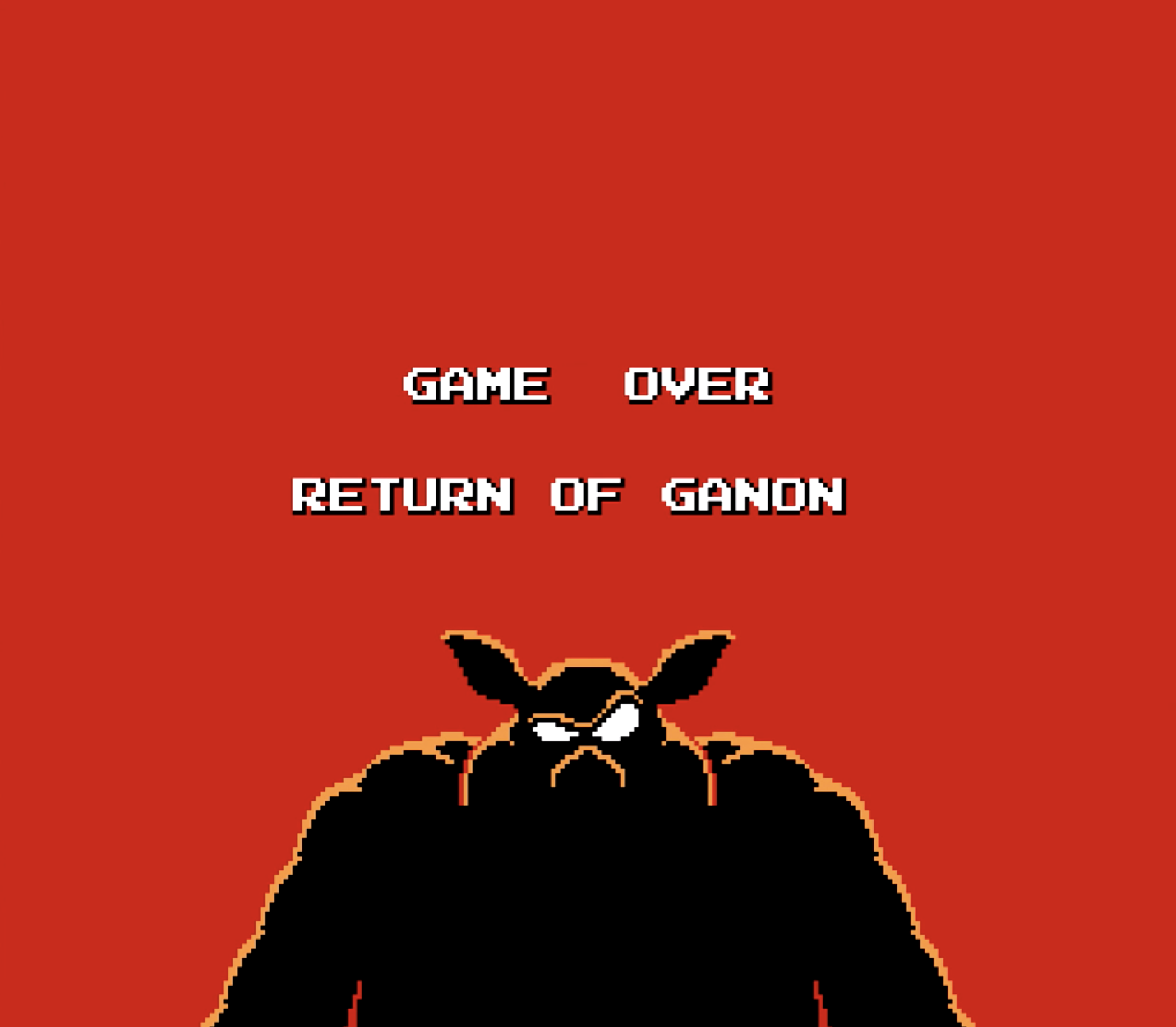

Zelda II: The Adventure of Link was also interested in terror, this time using an easily-overlooked game element to deliver a haunting image. Instead of a standard game over screen that just told players that they lost, Zelda II transitioned from a rapidly-flashing death screen to a stark red background adorned with Ganon’s silhouette and the words “Return of Ganon.” This marks the only appearance of the series’ longest running nemesis in the game. That fact is made all the more chilling by the game’s text explaining that Ganon’s followers were hunting Link so they could revive their Lord by sprinkling the hero’s blood onto his ashes. The NES sound chip so impressively rendered Ganon’s sinister laughter that it’s not surprising that the top comment on a YouTube video for this screen is “this gave me NIGHTMARES when I was like 5 years old.”

Featuring this kind of game over screen accomplished two things. First, creating a viscerally negative reaction to ever losing. The second, more important aspect, is that it showcased how the world of Hyrule existed outside of the player pressing the “power” button on their NES. The trials and tribulations of this world that players came to inhabit did not simply stop. When Link, and by extension the player, failed, there were dire consequences.

When Nintendo developed The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening for the Game Boy, they ramped up the spookiness. The game was directly influenced by Twin Peaks, itself a television series that bucked genre convention, combining soap opera melodrama, small town mystery, and surreal horror. Instead of playing each of these genres and tones separately or as merely pastiche, they blended with each other—often in uncomfortable or discordant ways—producing something that felt distinct. The game saw Link shipwrecked on Koholint Island, a dreamy place populated by strange inhabitants. While some, like the young heroine Marin, helped Link in his quest, there were also plenty of “suspicious types,” to use producer Eiji Aonuma’s own words. There’s no greater illustration of this than the Town Tool Shopkeeper.

The shopkeep is a strange, flitting man, a sinister, five pixel-wide grin never leaving his face. Visiting the Tool Shop let Link purchase items necessary to complete the adventure, such as the shovel and bow, and players would do so by picking them up and bringing them to the shopkeep for pay. Discerning players could also wait until the shopkeep looked away to take the item without paying. Doing so, however, sealed their fate. Visiting the shop from that point on had the shopkeep stop Link, call him a thief, and instantly kill him with a lightning magic spell.

When players reloaded their save, they could once again safely enter the shop, but from that point on, Link would be known to every NPC as “THIEF,” and their save file was renamed as such. Nothing short of deleting the save and starting a new game would stop this from happening. Why does this shopkeep know some otherworldly death magic? Why does his ire never abate, even if you spent the entire game away from the shop? How can he reach through the fictional world of the game and mark your—not Link’s, your—save file with an accusation? Link’s Awakening never answers these questions, and is all the better (and creepier!) for it.

Where things get really unsettling are during the game’s second half. (Heads up major spoilers for Link’s Awakening follow. Hop down to the paragraph after this to skip them!

In the end, we learn that Koholint Island, and all its inhabitants, are actually a creation of the dream of a flying whale deity called the Wind Fish. The Wind Fish won’t awake from its slumber due to a force called the Shadow Nightmare; their continued existence—and Link’s continued imprisonment—is dependent on the Wind Fish staying asleep. When players go to confront the Shadow Nightmare, its final form, DethI (“death-eye”), literally draws from cosmic horror, appearing as a giant, shadowy eyeball with spiked tentacles. After the player defeats the collective and awakens the Wind Fish to escape the dream, Koholint, and all the characters you grew to love and hate, cease to exist. It’s a pyrrhic victory. Even though the game lays out the stakes of Link being trapped there, waking the Wind Fish carries a mix of horror and melancholy. As Link goes off sailing onto his next adventure, he (and we) are the only ones who will carry the weight of Koholint and its history.

Fantastical Worlds, Eerie and Alive

This blend of melancholy and horror is elsewhere in the Zelda franchise too. Majora’s Mask is often called the creepiest Zelda game, but its smaller scope, more intimate story, and shorter length keep it from feeling overwrought. It actualizes terror in its structure and setting.

Fresh off the conclusion of Ocarina of Time, Link goes in search of his missing fairy Navi, and is met by the mischievous Skull Kid. Skull Kid has stolen a mysterious and powerful artifact, the titular Majora’s Mask. We’re tasked by the unassailable Happy Mask Salesman (what is it with Zelda and creepy merchants??) to retrieve the artifact or, in regular Zelda fashion, horrible things will happen. I don’t think I’ll ever forget his gross laughter as he asks us, “ You’ve been met with a terrible fate, haven’t you?” Initially depowered and forced into an unfamiliar body, we play out a time loop where in three days, a massive, sneering moon will fall and destroy the world.

It would be frightening enough to know that there’s a world-ending threat coming in three days, but Majora’s Mask goes the extra mile by having the moon approach in intervals, slowly taking up more of the skyline as time dwindles away. Time that we cannot help but face as the game slam cuts to a black title card with the number of hours left at the dawn of each new day. I remember playing through Majora’s Mask with my older sisters and struggling to even contend with the weight of time because it felt so crushing. Few games have captured that paralyzing fear since.

The time loop does, however, offer reprieve from the task at hand. You never have to accomplish all of the story in one loop, and Nintendo smartly chose to dot Termina’s countryside with plenty of goofy sidequests to pass away the time. The Zora and Goron transformations also offered a euphoric series highpoint in their movement capabilities, letting you slice through the water to jump out of it like a shark and roll across rugged terrain in a spiky boulder form, respectively. What grounds the adventure the most is that NPCs follow a set schedule that’s dutifully recorded in your Bombers’ Notebook, always letting us check in on characters we grow increasingly closer to. No matter how near the apocalypse comes, it’s calming to see all of them go on carrying out their daily routines. (Because honestly? Same.)

Then there’s the “Elegy of Emptiness” song. Activating certain switches in Majora’s Mask requires the player use an ocarina tune to create a statue that reflects Link’s current form. Except, “statue,” is not an adequate descriptor. It is more detailed than any statue needs to be. It has lifelike features, but the Link simulacrum has dead eyes and a horrible un-smile. Its teeth are so detailed. Its face is the worst. I hate it.

The Elegy of Emptiness statues also directly informed a great piece of horror fanfiction. Even if you haven’t played Majora’s Mask, you’ve might’ve heard of the creepypasta BEN Drowned. It’s a shining example of how Zelda fans have always been in lockstep with Nintendo’s own experimentation with horror. It’s a well told story, complete with a haunted garage sale N64 cartridge, a narrator who is slowly losing their grip on reality, and plenty of found-footage. While the footage is well-crafted modifications of Majora’s Mask content, it heavily leans on the source material for much of its terror, from the haunting Elegy of Emptiness statue to an inescapable assault by Skull Kid, who repeatedly dispatches and revives the player in much the way that the world itself faces constant, repeating obliteration.

Implicating the player and comparing our pursuit of power to Ganon’s is not a new idea, but since Zelda utilizes it so sparingly, it feels novel and scary in its own right.

To confront this crisis, Link must collect and master a series of masks that allow him to transform his shape. Each transformation that Link uses over the course of the game are the materialized sorrow of dead spirits of a Deku Scrub, Goron, and Zora, and each transformation is presented in horrifying, unskippable detail when Link first adorns each mask. Nintendo smartly does not let its grip up, and we’re forced to see the entire transformation sequence. Why? A Nintendo rep once explained via the Miiverse that “the boundless sorrow surrounding each mask comes rushing inside the wearer when they put it on.” The developers wanted players to know that each time we transform, we are communing with the dead. If it wasn’t a traumatic process, it just wouldn’t ring true.

While I might be down on Twilight Princess as a whole, it does feature one of the most chilling tableaus I’ve encountered in the series. During a seemingly normal recollection of the creation myth of Hyrule, Link, and more specifically, the viewer, are assaulted by a white-eyed doppelganger of Link’s childhood friend, Ilia, again like something straight out of Twin Peaks. Worse still, Link soon succumbs to this force and himself appears as a grinning, white-eyed doppelganger, hellbent on using his (and by extension, the player’s) growing powers to plunge the world into chaos.

Implicating the player and comparing our pursuit of power to Ganon’s is not a new idea, but since Zelda utilizes it so sparingly, it feels novel and scary in its own right. The last moments of the vision still stick with me, a seemingly endless series of Ilia bodies raining down, terrifying Link as he snaps out of it. If the Breath of the Wild sequel finds a way to incorporate that sense of dread in a world informed by its direct predecessor’s revolutionary setting, it’ll be something to beheld.

The sequel to Breath of the Wildwill have one advantage on past, horror-tinged Zelda games: It will be able to draw on a Hyrule that players have fully inhabited unlike any previous title. In Breath of the Wild’s Hyrule, players had to plan out journeys and respect the land they tread on, lest they get swept away by torrential rains while scaling a mountain or getting shocked by lightning while carelessly brandishing steel. It was a game you could feel perfectly content to just quietly contemplate the scenery in or to go out in search of potential and possibility. I’ve seen the game’s design cited as an example of decolonial fiction. Breath of the Wild’s Hyrule was not a space to be “conquered.” Thanks to its weather effects, physics systems, wildlife, and a mix of tangible locales, Breath of the Wild was a game with a sense of vitality unlike any other.

If those same creative energies and technologies that went into making that “thingness,” that sense of place a reality, were instead focused inwards, down deep below the depths of Hyrule, what would that even look like? Feel like? As we experience every texture of its world, what indelible marks will this new game’s dark lessons and uncomfortable truths leave on us?

Have thoughts? Swing by the Waypoint forums to share them!

from VICE https://ift.tt/2IWVi3T

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment