Brad Dixon can cycle at superhuman speeds, climb steep inclines, bank corners, and flow through downhill sections. He's so good, he can even grab a something from the kitchen while pedaling away.

That's because Dixon isn't really cycling. Instead, he's cheating Zwift, a popular game and 'smart trainer.' Zwift allows cyclists to compete in virtual worlds by removing the rear wheel of their real road bike and linking the rest of the frame to stationary "trainer," a device that controls the resistance of the bike and uses sensors to ultimately calculate their speed. You can think of it like World of Warcraft, only for riding bikes instead of slaying dragons.

Dixon, a security consultant from cybersecurity firm Carve Systems, researched how to manipulate the data traveling from the bike to Zwift, tricking the system into thinking he's pedaling quickly while not actually exercising at all.

"Ultimately I have an Xbox controller I can use to squeeze the trigger, make the little guy in the screen pedal harder, and I could [put it on] cruise control too, because who doesn't need to get off and grab yourself a beer or something while riding," Dixon told Motherboard in a video call. On Sunday, Dixon presented his research into Zwift and the virtual bike race ecosystem at the annual hacking conference Def Con in Las Vegas.

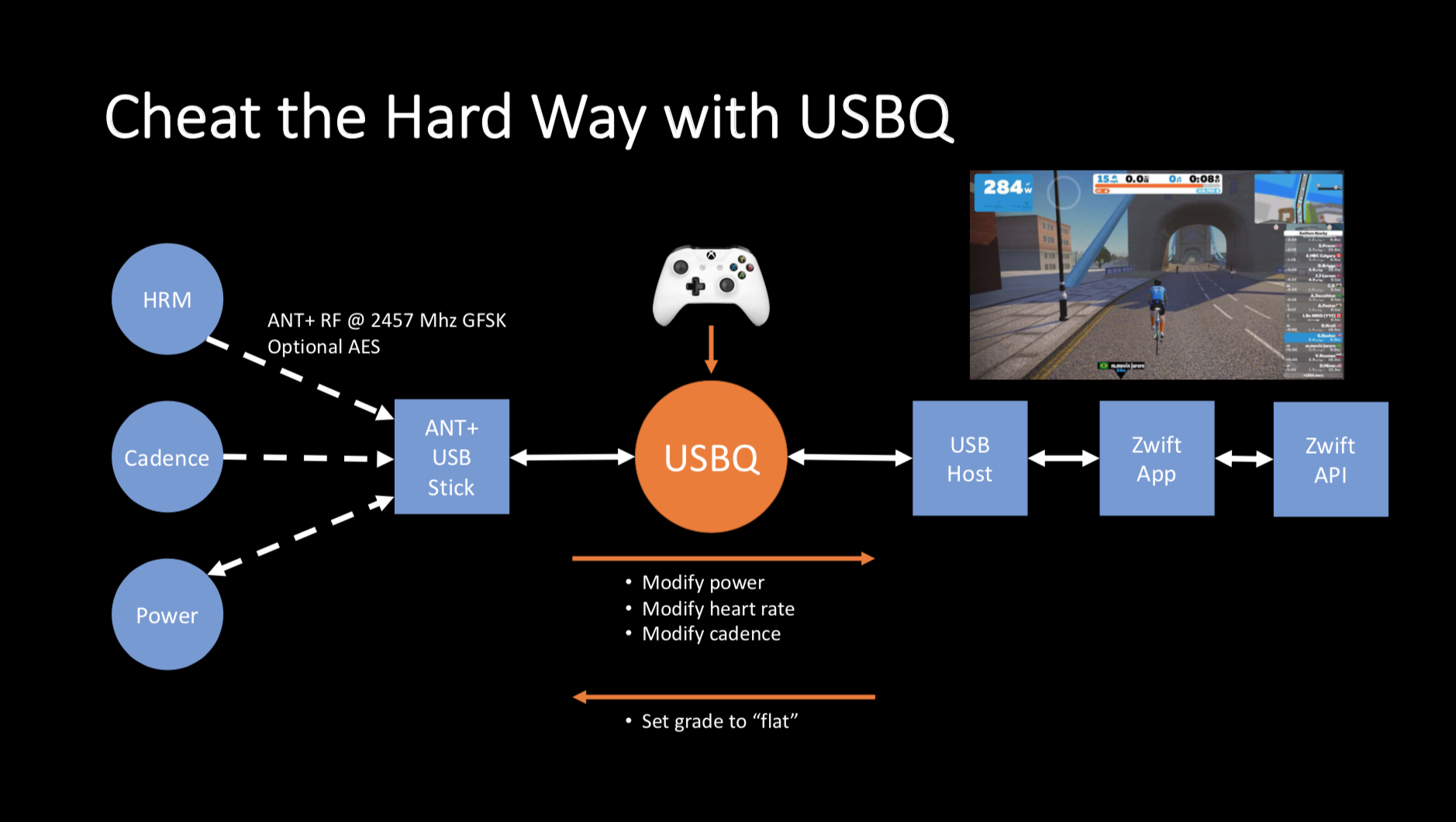

For the computer to determine the rider's output, they have to enter their weight and height into the system—lighter riders go faster. Then while riding, various sensors take readings which are then passed via the ANT+ protocol to the computer. Dixon explained that he used the open source toolkit USBQ on a small Beaglebone Black board, similar to a Raspberry Pi, to intercept and modify those readings. This essentially placed Dixon between the sensors and the Zwift app.

"Our objective from a technical perspective is to be able to modify what's called the 'instantaneous power reading' from the trainer, so that we lie to Zwift, and convince it we're pedalling really hard," Dixon said.

The research didn't exploit a vulnerability in Zwift, as much as it took advantage of how the system functions overall.

"It's incorrect to say that I hacked Zwift, because I didn't actually. There's not a vulnerability in there," Dixon said. "I don't think there is anything for them to fix. It's just the nature of the sensors that they're using and how it works are exploitable."

Mike Zusman, Carve Security's CEO and an avid cyclist, put the hacking into a broader context of cheating in cycling, with biological doping, and then cheating mechanically by manipulating a bike to be faster during competition.

"Then we get to things like Zwift, and online virtual cycling, which sorts of pulls it all together," he told Motherboard in the video call. "Cycling and cybersecurity collided for me."

Indeed, Zwift already sees some cheating. Derek Mead, VICE's own executive editor and serious Zwift and cycling fanatic, said in a GChat message "Everything in cycling is based on power-to-weight ratio, I can produce X amount of watts for 10 minutes while dragging my bike and my whole ass up a hill."

"So you have cheating nerds who care this much about Zwift going in and saying they weigh 50kg, when they actually weigh 80kg," he added.

"Basically, no one trusts anyone and everyone should cheat more. I want to hook a motorcycle up to Zwift so I can go 8,000 miles an hour," he said.

Zwift takes cheating seriously, according to Chris Snook, PR manager for the company.

"We have been aware of the possibilities of this sort of cheating on Zwift for a while, and we operate under the assumption that there are some bad apples who may be actively engaged in this sort of cheating. We have been pursuing a number of different approaches to tackling this problem, and have been doing so for some time," he wrote in an email.

Snook pointed to Zwift Accuracy and Data Analysis (ZADA); in competitions riders have to pass a number of tests to ensure the accuracy of their data, such as outdoor field testing

"Cheating is something all sports are challenged by and Zwift is no exception. Fair play is extremely important to us. Not just to ensure competition results are legitimate, but just as importantly, to ensure competition is fun for the vast majority of those using the platform to race fairly," he added.

See anything else worth reporting at Def con? We'd love to hear from you. You can contact Joseph Cox securely on Signal on +44 20 8133 5190, Wickr on josephcox, OTR chat on jfcox@jabber.ccc.de, or email joseph.cox@vice.com.

It's possible to cheat on your work-outs, if that's what you feel like doing. It might be possible to improve a cyclist in online races with these techniques, within limits, but it may be difficult for a hacker to fly under the radar.

"If you're Joe Schmoe, that nobody's ever heard of before and you're putting out pro-tour level wattage, people are going to question that," Zusman said. Dixon said he didn't use his approach in any competitions—he didn't want to mess with people who take this sport seriously.

It's unlikely a hacker at a real in-person competition could get away with Dixon's approach, however. It does require a piece of hardware to be intercepting the sensors' data, which may get noticed by onlookers.

Regardless, if your hacker friend starts putting out a lot more cycling power than you, maybe you should take a closer look.

"There's no way I can keep up with Mike on Zwift; this is my only hope," Dixon said.

Subscribe to our new cybersecurity podcast, CYBER.

from VICE https://ift.tt/2Kv2MvH

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment