It’s 2019, and if most of our dystopian nightmares haven’t already come true—out-of-control populism, over-surveillance, mass extinction, the dissolution of IRL human connection—they’re on the precipice of actualizing as we speak.

Take, for instance, our longstanding fears about genetic technology being used for Frankensteinian experiments with potentially catastrophic results. Our speculation on what this type of experimentation goes back centuries; Frankenstein was published in 1818, and it’s been 23 years since we were introduced to Dolly, a sheep who became the first animal successfully cloned from an adult cell. Since then, we’ve wondered when the first human clone—or worse, a human-animal hybrid—would show up to blow our minds. In the more than two decades that have passed since, we’ve heard rumblings of advancement in cloning technology—take, for instance, Barbra Streisand’s now-infamous choice to clone her dog—but nothing so major on the horizon that it’s shaken us to our core.

Until now, that is. According to Nature, the Japanese government has approved the development of animal embryos containing human cells, which could then be transplanted into surrogate animals and grown to term. Then, in a totally normal move that is not at all a sign that our god complex has gone totally awry, scientists may be able to harvest the organs of these hybrid creatures and transplant them into people, says Hiromitsu Nakauchi, who leads these teams at the University of Tokyo and at Stanford University in California.

Yep, “humanimals,” in some form, are pretty much here.

Since Dolly, there has been ongoing chatter about the ethical implications, both positive and negative, of cloning humans or genetically altering our DNA by splicing it with that of other organisms. In 2013, reports emerged of stem cells being successfully grown from cloned human cells—but they never developed into anything resembling a living, breathing person—and in 2017, a lab in California (also headed by Nakauchi) created pig embryos that contained human DNA; they were destroyed after three to four weeks.

This all raises just one question: Have these scientists never seen Splice?!?!

Most of the representations of cloning that we’ve seen in popular culture have been harrowing; for instance, Never Let Me Go, in which the human race raises clone children to adulthood, only to eventually harvest their organs, then kill them; Blade Runner, which has a similar plot, but in a cooler setting with more neon lights and monotone dialogue; The 6th Day, wherein Arnold Schwarzenegger must fight an evil corporation that’s illegally cloning people for nefarious purposes; and of course, the aforementioned Splice, wherein two horny scientists create an animal-human clone that wreaks utter havoc on their lab, their relationship, and their lives.

There’s just no way that whatever Japanese officials greenlit these ‘humanimals’ have seen Splice, because if they had, they would have immediately put a big red stamp of HELL NO on this project. It’s a true cautionary tale for the ages, and one that begs reexamination, because it’s also one of the weirdest movies to ever achieve wide release.

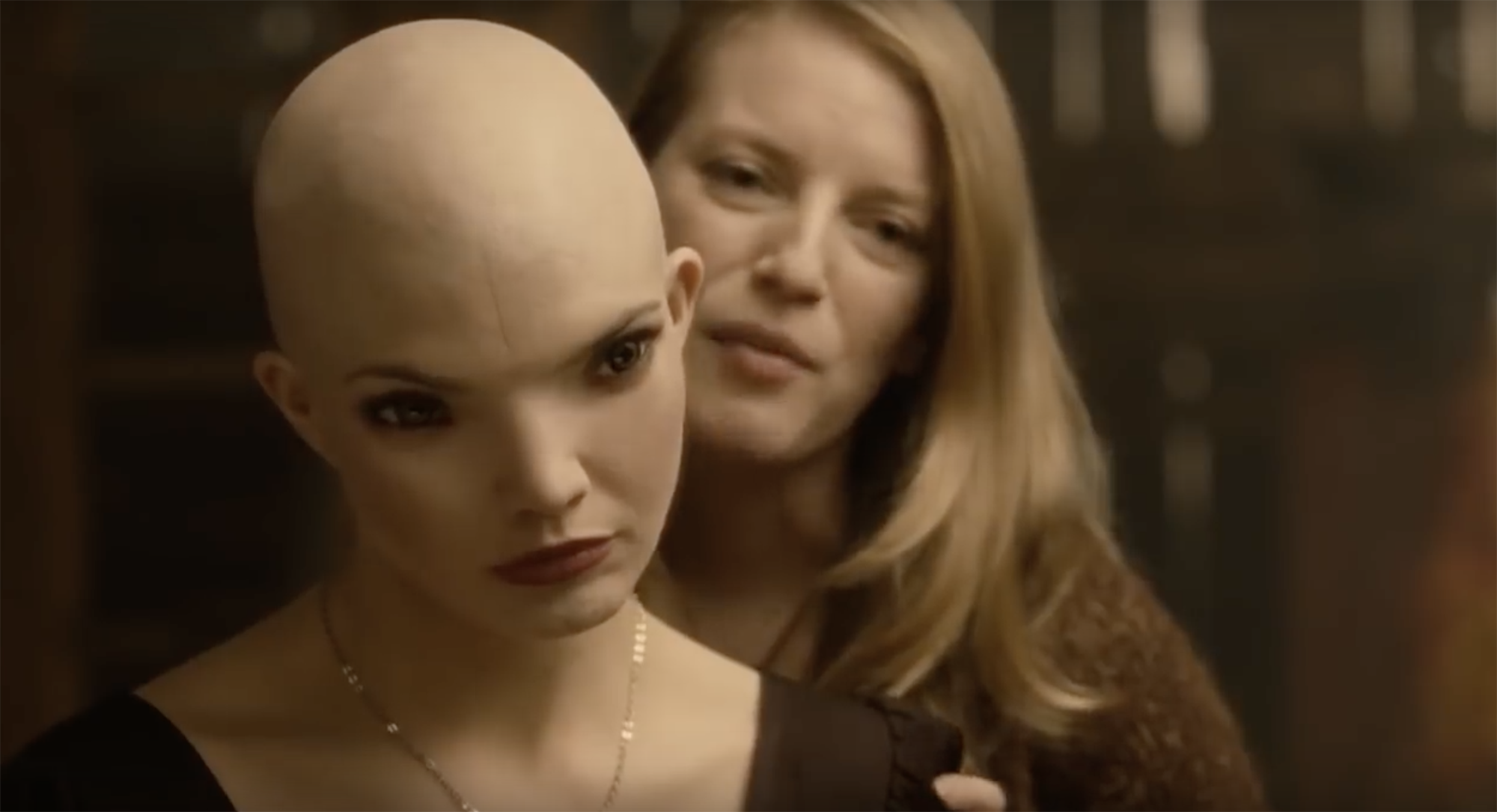

The 2009 film, which entered US theaters in June 2010, introduces Clive Nicoli (Adrien Brody) and Elsa Kast (Sarah Polley) as two young genetic engineers who aren’t like other genetic engineers; they’re cool genetic engineers. They have long, disheveled hair and listen to punk rock and still have sex on their couch years into their relationship. After the funding is pulled from their DNA-splicing research for a pharmaceutical company, they decide to continue conducting experiments in secret, which is how they end up creating a bald, chicken-legged, beady-eyed little monster that Elsa inexplicably becomes wildly attached to despite the fact that it's hideous, mauls her hand, and has a venomous, razor-sharp stinger coming out of its tail.

If you don’t wish to read any spoilers, stop here—but trust me, you’ll want to read them. It will either save you two hours of your life or make you want to see the film more, depending on your level of mental perversion.

Elsa names the horrible, raw-chicken-looking thing “Dren” (yep, that’s “nerd” backwards!) and starts treating it—or, rather, her, as they deduce that it’s female—like her baby, while Clive looks on in panicked disgust. Dren’s rapid growth cycle means that within weeks, she’s toddler-sized and learning how to spell with wooden blocks. Elsa even puts her in baby clothes, with a level of maternal desperation comparable to those people who are obsessed with hyper-realistic baby dolls. Clive, increasingly convinced that raising a humanimal is actually a terrible idea, tries to drown Dren in a sink, but to his surprise, she evolves and adapts the ability to breathe underwater on the spot. Elsa: delighted. Clive: losing it.

Dren keeps growing and is soon the size of an adult woman and also… kind of hot, in a Star Trek: Deep Space Nine kind of way. They move her to a remote barn to keep her off the radar of their employers, where she continues to become both hotter and scarier, killing and eating animals with her bare hands while also trying on Elsa’s makeup and committing increasingly alarming acts of teenage rebellion. She’s suddenly showing favoritism toward Clive, who is more relaxed around her—and even flirtatious—over time, and pushing back against Elsa, the disciplinary mom figure.

What transpires next is really what pushes Splice into the categories of both “legendary” and “traumatizing.” I’ll skip through some plot development and cut to the chase here: Clive has sex with Dren.

As these things often do, it starts off with some innocent dancing. A little hand-holding. Some levity.

As a viewer, you start to wonder if this is crossing the line into “very inappropriate,” but you remain transfixed.

Elsa and Dren's quarrels become increasingly intense, and Dren seeks solace in Clive's arms. There's a passionate kiss, then a "but, we shouldn't" moment. Then, once you aren't even sure what you're rooting for anymore, since this has all gone so completely off the rails, you come to and realize you’re watching Adrien Brody (pardon my language) fuck his daughter-science-experiment-alien creature. You wonder if this is even anatomically possible, but it’s happening right in front of you, so you have no choice but to accept that it is.

Then, Elsa walks in. Needless to say, she’s upset. Being cheated on with your shouldn’t-be-alive, not-even-human, part-scorpion lab clone might be even more upsetting than being cheated on with another real adult woman. Men, do better.

Some more horror-movie-ish stuff happens after that (Dren escapes, she’s now super dangerous and bloodthirsty, she can fly), but it’s also necessary to mention what happens at the end of the film. Dren spontaneously changes sex, kills Clive, and rapes and impregnates Elsa. What’s more, Elsa decides to keep the baby—ostensibly as a paid experiment for the pharmaceutical corporation, but really because she is gunning so hard for motherhood that she’s no longer concerned with endangering herself and the human race.

Splice has a lot of takeaways, but one important one is this: Do not mix human and animal DNA for a lot of reasons, but one of them is because if the ensuing creature ends up being surprisingly attractive, you might destroy your relationship and the ecosystem in your horny pursuit of it. And then, it will kill you anyway. The Clive/Dren sex scene is so troubling that it even made it into a YouTube roundup called “7 Creepy Movie Sex Scenes that Will Scar You For Life,” and it 100-percent deserves to be in there.

But for its heavy-handedness and utter insanity, Splice really does bring up some interesting points about the ethical decisions we would have to make in a world where there are sentient entities running around that are only part-human. Will they only have part of our emotional capacity? What if they have our intelligence, but the less-empathetic drives of other mammals? And do they deserve the rights of "real" people?

“Why the fuck did you make her in the first place?,” Clive yells at Elsa in one scene. “For the betterment of mankind?”

These issues may still seem far-fetched, but with this week’s announcement about that Japanese research, they’re worth considering more than ever. Again and again, government agencies have ruled that cloning humans is not a good idea. The National Institutes of Health has forbidden any government funding from going toward this type of research since 2015. (We reached out to them for comment on this week’s announcement, but never received a response.) Back in 2007, the United Nations released an urgent report warning that “Human reproductive cloning could profoundly impact humanity” and warning that if humans were to be cloned, they could be subject to “prejudice, abuse or discrimination” if their rights were not explicitly protected. And last year, Discover magazine wrote, “Long before Dolly the sheep was cloned almost 23 years ago, science fiction writers have fantasized about armies of look-alikes wiping out the rest of humanity, or clones bred solely to sustain their identical ancestors. The idea of clones is unsettling because it violates the fundamental moral understanding that we are all different and equally valuable.” Yet, scientists continue to find loopholes and trudge forward.

It’s unsettling for a lot of reasons—and sometimes, those reasons are best appreciated through sci-fi films that dare to be as messed up as Splice. The justification may be that we can save lives by growing human organs, or by testing drugs, or studying diseases on not-entirely-human subjects. But as we see in Splice, this is quite a slippery slope.

"The scientists should kind of imprison their creature, and in turn we would start to see the monster emerge inside, from the humans," director Vincenzo Natali explained in an interview about the film. Perhaps, he suggests, we should worry less about what havoc the creatures should wreak, and more about what our treatment of them could reveal about us as people.

from VICE https://ift.tt/2GHlder

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment