In what's become an annual Halloween tradition here at Terraform, Geoff Manaugh brings us an unsettling and mind-bending work of speculative fiction—this time delving into the untapped recesses of our unwaking lives. Enjoy. -the ed.

The lights in the room began to redshift, assuming a nostalgic yellow hue that reminded the man of the incandescent bulbs in his childhood bedroom. Objects looked tea-stained, antique. Small blemishes appeared like watermarks on the cream-painted walls. The transition was so slow the man didn’t notice it at first, until the room was the color of burnt orange, like the light of a campfire, then the red of a desert sunset, then something much darker, like barrel-aged wine.

The man responded exactly as they said he would, his eyelids growing heavy, so heavy they fluttered, before, against his will, he closed them.

The room went dark.

*

The word dormitory, his guide had explained as she stood facing him in the elevator on their way up to the top floor, his floor, where he would be staying for the next five nights, means place of sleep.

“It comes from the Latin word dormire,” she’d added. “The English word should actually be dormitorium, of course. Like auditorium. A place for listening. That comes from audire. Which means ‘to hear.’” The guide was young, had short hair, and seemed excited by etymologies. She had introduced herself in the lobby by name, but the man, to his embarrassment, had missed it.

Seeing his lack of reaction to the subtleties of Latin vocabulary, the guide smiled and changed the subject. “You’ll dream well here,” she said instead.

The elevator chimed. Its steel doors slid open. A long hallway stretched beyond, blue LEDs glowing along the floorboards like airplane safety lights.

“What’s that they say about going through doors in a dream?” the guide asked.

The man laughed. “I have no idea,” he replied. “What do they say?”

She moved out of his way and gestured forward. The man stepped through.

*

The building was a converted college dorm near the city park, in the heart of downtown, across the street from a mattress shop called Slumberland. That, his guide said, was a mere coincidence. With its ornate façade of worn brick punctuated by limestone-framed windows, the place exuded an old-world charm, its masonry walls giving the street a honeyed, geological glow every sunset.

Until five years ago, when a massive new campus development near the river had made the building redundant, it had been part of the university’s residential system. Rather than tear it down, the school had given it over to the neuroscience department next door; using federal grants and a donation rumored to have been as high as $60 million from a Swiss computer-memory billionaire, the neuroscience department had tunneled through the adjoining walls and was remaking the place from within. This former dorm was now set to become the most advanced sleep-research facility in the United States. Smart lighting, 3D laser-projection, immersive surround-sound audio in every room, and brand-new MRI machines in a lab whirring away on the basement floor. Apparently, only an institute in China was better-funded.

The man was there for two reasons: to make what sounded like easy money—$1,000 a night for a 5-night, all-inclusive stay—and, in return, to participate in a sleep study that had something to do with dream recollection, but the man wasn’t in it for the science. He had already made a list of things he wanted to buy with the extra money and he was counting down the days until he could spend it.

The initial questionnaires had been simple enough to game, he’d thought. They had asked if he had vivid dreams—he did, so he wasn’t lying, but, given the context, who would have stated otherwise?—and whether he was a deep sleeper. The right response to that one was harder to judge. The man had hedged, and wrote, “Usually.” Finally, he gave them permission for a police background check and submitted a set of fingerprints.

He was accepted into the program.

*

The man’s accommodations for the next five nights were more spacious than he had expected. It was, in fact, a suite. Its main room featured a double-height domed ceiling that brought to mind a planetarium. (A planetarium, the man thought: a room for planets. He almost said something to his guide, but refrained.) There was a small kitchen and an array of modern furniture—a table, chairs, empty shelves. The bed, in a separate room with heavily soundproofed walls, was king-size, with a tasteful blanket like something he’d see in a design magazine. At the very least, the man would be comfortable.

On the other hand, much of the building remained unfinished. Nearly every door in the corridor leading to the man’s guest room had small piles of tools outside, including buckets spattered with paint, and he had heard a distant droning sound. It could have been HVAC, but the man thought it was someone sawing.

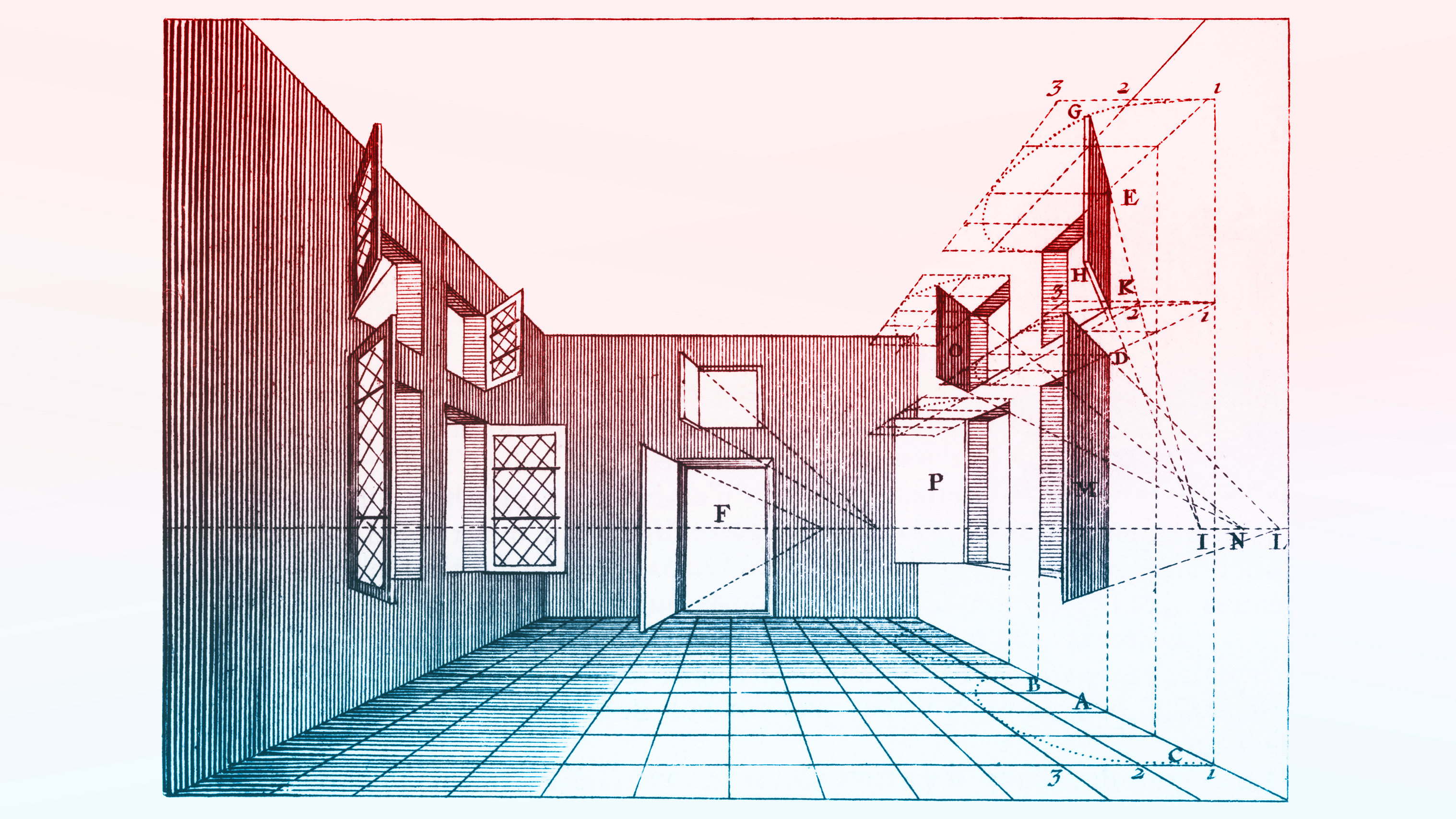

Picture hooks had been installed on all the office walls, he saw, but only one actually held anything. The man walked over, leaned in. Ignoring his own reflection in the glass, he saw two Renaissance engravings placed one beside the other: they showed the same room, drawn according to precise lines of perspective, but one had most of its doors and windows closed, the other, all those apertures thrown open.

“Damn it,” his guide whispered behind him.

The man turned to see her fidgeting with a remote control in front of an enormous TV. She seemed flustered. The logo of the unit’s manufacturer gleamed on-screen. Finally, she managed to change the channel and the logo disappeared, replaced by an image of the building they were standing in. It took the man several seconds to realize it was not a photograph but a live video feed. Just thirty minutes earlier and he would have been on it, heading inside to this very room.

For all the luxury, the man thought, it felt like he’d arrived a week too early. The building wasn’t ready, nor was its technology; for a sleep study, of all things, the whole experience seemed strangely rushed. The man imagined work crews stomping up and down the corridor at all hours while he tried to sleep, and he wondered if he would hear them. He wondered if he would dream about them. It was a building made for dreaming, he thought, but what if he dreamt of the building itself?

“Your study-lead will be here in a half-hour,” the guide said, checking her phone. “In the meantime, feel free to unpack or read through the manual.” She pointed at the desk. “It explains how to use the room.”

The man must have looked baffled or unprepared, because his guide smiled again and asked him if he was okay.

“Of course,” the man replied. He glanced around the room, at the domed ceiling, at the TV that had already switched back to its manufacturer’s logo. “Just taking it all in.”

*

The psychologist slid a folder across the table toward him and told him to take a look. Unlike the guide, she was older than the man, by at least a decade, and was wearing formal business attire.

The folder, he saw, held four photos arranged in a grid, each image depicting a different building. There was a warehouse, a corporate office that appeared to be abandoned, a strip mall, and a suburban home. The photos were black and white, clinical, neither stylized nor artistic, almost like crime-scene photos.

The man scanned each image, one to the next and back again. He wasn’t sure what he was being asked to do.

“What am I—what am I looking for?” he said. “What is this?”

The psychologist held a stylus in one hand, a tablet computer leaning against the edge of the table between them. He couldn’t see what was on the screen.

“One thing we’re testing,” she said, “is memory and projection.”

“That’s two things.”

The psychologist paused, ignoring the remark, her gaze moving from the man’s face down to the photos. “We want to test different source materials to see how they influence dreams. Visual cues. Audio cues.”

At first, he thought she’d said clues.

“Do you work for the school?” he interrupted. The man was restless; he had walked into the building only an hour earlier and the reality of spending five days there, in a windowless suite cut off from the world, was starting to unsettle him. He needed easing in.

“The school?”

“The university,” he said.

“Oh—no, we’re federally funded. That was all explained in your contract. We’re just using these facilities. Renting them. It’s a bit of a rush!” The psychologist smiled apologetically. “In fact, we’re the first people in the building.”

“How many other people are here?” he asked. “In the study. Am I the only one?”

“Would that disturb you?” she said. “Would you hesitate before entering an unfamiliar building on your own?” The psychologist seemed intrigued by this.

“Of course not,” the man lied.

“Good. But there are many others, on different floors. I’m meeting three more participants after you, and we brought on six yesterday. Then there’s tomorrow. And we discharged five last night.”

“Wow,” the man replied. “What’s the rush? I mean, for a sleep study, why so—”

“Timelines,” the psychologist said, cutting him off. Her response was vague, her previously apologetic smile now empty. “Shall we continue?”

“Of course.”

“This study works with cues,” she repeated. “Things that might affect the content and meaning of dreams. In this case, we want to start with buildings.”

“Buildings?”

She slid another file across the table. It seemed exactly like the others: four buildings in the city somewhere, one with a CLOSED sign hanging in its front door. The man could see reflections of clouds in the building’s upper windows and bits of trash outside on the sidewalk.

“Wait,” he said, disappointed, “is this about architecture?”

“It’s about memory,” the woman corrected. She stood up and gathered her files. “And projection.”

“So it’s about two things,” the man replied.

*

“Are you awake?”

The question shocked him. The man looked around the room, at the psychologist across the table from him, at the blue lights illuminating the domed ceiling overhead, at the personal objects he remembered unpacking mere hours before. How long had he slept? An hour or two at most, the man thought. The only thing he knew was that strong digital lights had turned on, emitting a harsh blue glare, he had stumbled into the front room, and the woman walked in just a few minutes later.

This, he would later learn, was called blueshifting.

“I think so.” The man glanced down at his hands, as if trying to see through them. They seemed reptilian in the synthetic blue light. “Yeah,” he said. “I’m awake.”

“We wouldn’t want you confused about that,” the psychologist replied. “What did you dream?”

The man exhaled. “God,” he said, “give me a minute. I need to remember.”

After some false starts, the man described a series of unfinished dream sequences. A subway ride where the stations made no sense; a conversation with a girlfriend who, in reality, was just a woman he often saw at the gym; a walk down a street with some buildings—

The psychologist interrupted him. “Describe the buildings,” she said. “Were they in the photos you saw? Try to remember.”

The man thought for a second. Everything had happened so quickly, he had nearly forgotten the photos.

“That’s a good question. I don’t know. They were like anything you’d see on a main street. Hardware stores. Liquor stores. Maybe a bank. Can I—can I see those photos again?”

“No.”

Memory and projection. They assessed one another.

The psychologist tapped something on her screen. “Try to remember the businesses. Think carefully. Every detail is important.”

“That’s all I remember,” the man said. “You know, let me get into the swing of things, sleep some more, dream some—”

“It’s a very short study. We have timelines.”

“Okay,” the man said, “okay.” He still didn’t understand what could be so urgent about a sleep study, but he would roll with it. “One of the businesses. It was, like, a paint store.”

The psychologist stopped writing. She stared at him.

“Is that—wrong?”

“No, no, a paint store,” she replied. “That’s great. That’s interesting.” She tapped her stylus against the screen, thinking. He got the impression she was hiding something, keeping details to herself. “Anything more?” she asked.

The man shook his head. “Not really. No.”

In the silence that followed, the psychologist reopened one of her files. She flipped through a collection of paperwork inside, pulling out a photo that she placed face-up on the table. “Did it look like this?”

The man looked down at a black and white photo of the paint store from his dream.

“ Holy shit,” he whispered. “Sorry—it’s… That’s amazing. That’s the paint store.” He picked up the photo, as if to prove it was real. “How did you do that? How did I do that?”

“That’s what we’re studying,” the psychologist answered. “We’re going to add something new this time. Are you ready?”

He held out his arms. “I’m a captive audience.”

“A mother’s first role,” the psychologist said, “is to protect her children.”

The man laughed. “What?”

The psychologist repeated herself.

“Are you asking me if I agree with this statement?”

“Agree or disagree,” she said, “it’s just a prompt. Like the photos. ‘A mother’s first role is to protect her children,’” the psychologist repeated.

*

Getting to sleep this time around was nearly impossible. They had given him a plastic bottle full of supplements that the manual described as similar to melatonin. Non-habit-forming. 100% natural. Clears the system in less than an hour. If he ever had trouble sleeping, they’d said, a single capsule could coax him back to dreamland.

He swallowed two.

* * *

The man blinked in the blue light, groggy, half-asleep.

“What did you dream?” the psychologist asked.

The man thought for a second, regrouping. He said he had walked further up the street—the same street, he emphasized, amazed by this. The same street, he said again. He had even dreamed the same buildings. “It was the same damn thing!”

“That’s perfect,” the psychologist said. “That’s exactly what we want.”

Although it was nearly night, the man continued, the sky was a deep mineral blue, like a medieval painting, and the sun was somehow streaming up, he said, casting strange, narrow shadows down the block. And, the man added, remembering something, the streets were empty. No one was out—no one, anywhere—but that made sense. He couldn’t see it, but, the man knew, there was some sort of event nearby, like a sports stadium. Everyone was there. They were watching a game, leaving the streets deserted.

The psychologist nodded, taking notes. “You said the sun was shining upward. Could that have been the stadium lights?”

“Huh,” the man said. “That’s interesting. You mean, were stadium lights shining up into the sky?” He nodded, thinking it through. “Yeah, you might be right.”

“Excellent,” the psychologist said. “Excellent. Was there anything else?”

The man thought, then shook his head. “No,” he said. “I think that’s it.”

* * *

The psychologist had ended the interview with a new prompt, playing the man an audio recording. It sounded like noises picked up in the back of someone else’s phone call. Accidental sounds, like passing traffic or stadium noise. The man couldn’t tell.

But very quietly, almost imperceptibly, there was something else.

The man heard a quiet voice.

A kind of whisper.

*

“What did you dream?”

The man blinked. The light in the room was like staring at a computer monitor.

“I was walking,” he answered, “toward this—this really creepy building. Up the street. It was starting to rain and I walked up toward the front door. But I didn’t look inside. I sort of stood there, beneath an awning. I could hear a distant crowd roaring. I knew… like…”

The psychologist waited. “Yes?”

“I had this feeling.”

“You had a feeling?”

The man said he knew someone was inside—watching him. No, no, not watching him, he corrected. The man thought for a minute. He had a feeling someone was waiting for him. Waiting for him to arrive.

The psychologist seemed very interested in this.

“Where was this person?” she asked.

Where, not who, the man noticed.

He made his way back through the dream slowly, almost reluctantly. The truth was, the man knew, something about the dream had rattled him. Someone inside the building wanted him to arrive—because they were lost. They were trapped or perhaps caught by something—he couldn’t tell. He just knew there had been a terrifying weight to this knowledge, a sense of genuine horror.

“I don’t remember,” the man said. “I just knew it was a boy.”

The psychologist leaned forward. “A boy,” she said. “Tell me about the boy.”

The man adjusted himself, sitting up straighter. “I didn’t know much about him. In the dream, I mean. I just knew he was inside and I could help him—I could find him. The boy wanted help. Does that make sense? He wanted to be rescued.”

Hearing himself speak, it felt resonant. Symbolic. He was going to rescue a trapped boy.

The psychologist began writing something. For the first time, he thought, she seemed excited.

“There was definitely a boy inside?”

“Yes,” the man said, encouraged. “A boy who—who didn’t know how to get out. He needed me to find him.”

The psychologist was nodding, writing things down.

“This is interesting—very interesting,” she said. “Okay, let’s get back to the building.”

*

They went back and forth like that for several sessions, an interview every four hours, the man disoriented both by lack of sleep and by far too much of it, the psychologist offering several more prompts along the way (“The first one into darkness turns on the light,” she’d said, then she’d brought out more photos, this time of different men). Each dream, the man inched further down the street, gathering more details, the shock and familiarity of redreaming the same scene quickly wearing off.

When the psychologist casually remarked how much time had passed, the man was astonished. These breaks between sleep, filled with questions, had become such a blur that time in the world outside had disappeared entirely. As part of the study, of course, the man had signed away his electronic devices and the room itself had no clocks.

His only remaining connection to the world now was the live TV stream of the building he’d been sleeping in. Whenever he looked, he saw cops out front, entering and exiting, often one man in particular, a black cop with a kind of handlebar mustache, talking to his colleagues on the stoop. Was there a police station nearby?

It’s already been two days, the psychologist said. Two days. The study was moving quickly. The man was doing great, she added, but they were nearly at the halfway point and they needed to step things up. This was essential—even urgent.

The psychologist pressed the man, in his next dream, to go inside. Open doors. Peer through windows. If the boy wants to be rescued, she said, let’s rescue him.

“We need you to be confident,” the psychologist explained, “If you see a door, we need you to open that door. If you see a closed room, we need you to step inside.”

The man fidgeted with his hands, cracking a knuckle.

“Don’t be afraid,” the psychologist urged. “They’re just dreams.”

*

The man inhaled and held it. A long sigh. “I had kind of a nightmare this time,” he said. “I didn’t like it.”

“Oh?” the psychologist replied. She sounded unexpectedly pleased.

Sitting beside her this time was a man. In his mid-forties, with greying hair swept back away from his face, he looked attentive, focused. She had introduced him as an architect.

Speaking to both of them, the man described his dream. That building with the boy—it was a kind of warehouse, he said. No, it was like the building next to a warehouse, like an office or business headquarters. Maybe two or three stories tall. Small windows.

“The windows faced east,” the architect said.

It took a few seconds for the man to realize it wasn’t a question.

“What do you mean?” he said. “How do you know that?”

The architect looked at him, as if judging how much he should say. “There are certain archetypes—universal forms or symbols—that come up again and again in architectural dream analysis. We see them all the time. Houses on steep hills, cabins in the woods, dark office towers in the city at night. Each has its own meaning. Eventually, you start to see patterns—including where people dream windows will be. Windows facing east in a dream mean something different than those facing west.”

The man nodded, debating whether or not this was all bullshit, but also realizing he had no idea how to tell what direction the windows had been facing.

“You said it was sunset,” the architect explained, as if reading the man’s mind. “You said earlier that the building was backlit, against the sun. That means you were facing west. So the windows you saw would be on the east side of the building. Correct?”

The man nodded, impressed by the logic. “That actually makes sense.”

“As you can see,” the psychologist broke in, “I brought along an architect because I thought he could help with the details. He can model buildings, make adjustments. Is that right?”

“That’s exactly right. I can build a model of your dreams with basically any details you tell me. Then we can use the model to spur more memories. We can add colors, window treatments, the sizes of specific rooms and hallways. Want to see an example?”

“Of course,” the man said.

The architect asked him to go back through his dreams, from the beginning. The row of shops along the street. The paint store. The warehouse building. The approximate location of the sports stadium. If there were any cars parked out on the street.

“Okay,” the architect finally said. He placed his laptop down on the table and pointed up. The man and the psychologist both craned their heads back. “Based on our interview,” the architect said, “this is the street you’ve been dreaming. Take a look. Let me know if it’s accurate.”

An image appeared, projected into the middle of the dome, hovering there like a plane of light. Using what resembled linked thimbles on both his thumb and forefinger, the architect began turning his hand in the air.

“This changes the depth of field,” he said, “so we can—” The architect twisted his wrist and the model snapped flat. “—zoom in to various degrees of detail.” He stretched the model open again, expanding it. “Do you recognize anything? Take your time.”

The man grinned despite himself, amazed at the model rotating above.

“Do you recognize anything?” the architect repeated.

“I do,” the man said. “It’s incredible.”

The effect was uncanny: the man was looking up at a digital reproduction of his dream, down to specific building fronts and loose trash. It was as if the architect had seen this street before and had had a model simply cued up, ready to go.

Nevertheless, the man saw, it wasn’t perfect. Some details were wrong. He thought the roofline of one of the buildings had been higher in his dreams, for example. He had also stood beneath an awning, out of the rain, but the awning was missing.

Other than that, he said, it looked great.

“You said it was more of a nightmare this time,” the psychologist prompted. Her face glowed in the light of the man’s dream shining above. “Why?”

“Because I went inside.”

*

The man had noticed something, but he didn’t want to mention it. Not yet.

His dreams were changing.

He hadn’t said anything at first because he wanted to see where this was going, but he thought he had figured it out. The study. He thought he knew what they were really testing him for.

The man was dreaming about himself, he thought. In fact, he was confident: he was the boy who was lost somewhere in the city. He was the boy who was trapped. The whole thing was a symbol. A metaphor.

The boy he was trying to rescue was himself.

The study, the man thought, increasingly convinced of this, was a form of experimental therapy.

Rescue the boy, the man thought, because the boy is me.

*

“You went inside,” the psychologist replied. “That’s excellent. Thank you. What did you see?”

The man had walked into the building, he said, past a desk, toward a small stairwell and hall. At the top of the steps was a corridor with black doors stretching away into the darkness. He knew the boy was up there, he said, trapped behind one of the doors, but he had the feeling someone else was in the building with them. Listening to his footsteps.

The psychologist seemed too excited to speak.

“Were there any lights inside?” the architect asked, filling the silence. Even the architect’s bearing had changed, the man noticed. Poised, concentrated. Alert.

The man said, yes, he remembered a faint glow above one of the doors. “There was a light sort of inside—” The man closed his eyes to remember. The light wasn’t coming from the first room, he thought, but somewhere deeper inside the building, further back, from a room behind the first room. The boy, he said, was back there.

The architect started typing something into his laptop as the psychologist jotted notes. He must be onto something, the man thought. The conversation felt driven, intense.

“Can you tell us how many doors there were?” the architect asked. “In the hall? Do you remember?”

“Christ,” the man said, “this—this is really a test.” He thought for a minute, pushing himself. The man closed his eyes again—but there was something wrong. He was distracted. It wasn’t the building that was confusing him. No, it was the sky. He remembered the sky, and the stars, and the way the trees had cut black silhouettes against the building. It was all familiar somehow.

“The number of doors,” the architect insisted. “Let’s start there. Count down the hall until you get to the door with the boy.”

“Please,” the psychologist said. “We’d love to know.”

She and the architect both stared at him across the table, expectant.

“Okay—there were… like…”

It was the trees, the man realized. He had seen those trees before. It was the view from his childhood bedroom, their branches against the sky. The same stars. He had seen it every night, looking out at the world, lying awake. His dreams had changed to depict his own childhood house.

“Sorry,” the man said again. “I don’t remember.”

The psychologist slumped in her chair. “There is a lot riding on this,” she said. “We need to find the boy. Do you understand? We need to do it soon.”

The man just looked at her. “I want to find him, too.”

*

“I added some details here,” the architect said, looking up at his own model. He had changed his clothes before the session, which seemed like a deliberate way to mark the passage of time.

He pointed up at a small door beneath the stairs. “Most buildings of this era tend to have that sort of thing,” the architect said. “A crawlspace. A kind of storage closet. Does that look familiar? Did you see that?”

The man closed his eyes. “I think so,” he said. “Yes. I… I think I walked past that.”

“Do you remember a lock on the door?” the architect asked. “On the outside of the door?”

The man tried to remember. “I saw something there, yeah. Like, three—three circular objects. Vertically, in a row. One, two, three. Were those locks?”

The architect typed something into his laptop, looked at the screen as if to check the results, then glanced back across the table. “Potentially,” he said. “Next time, pay close attention to that door. Specifically, how it’s locked. We might need to get inside.”

“Got it,” the man replied. He started to say something else, then stopped, chewing his lip for a second. They both waited, expecting him to continue the description. Instead, he said, “It’s… it’s been longer than five days, no? This is day six. Maybe even day seven.”

The psychologist’s expression dropped. “No,” she said. “That’s not right at all.”

“Are you sure? I think it’s day six.”

The architect fiddled with his laptop, as if no longer a part of the conversation.

“There is still time left,” the psychologist answered, speaking slowly now, as if the man was a very slow child, “but there won’t be if we don’t find which room the boy is in. Do you understand?”

The man had to admit, they seemed as committed to the idea of him finding himself as he was. He liked that. He thought of the five thousand dollars they were paying him, of how close he seemed to be to finding the boy—to finding himself—and he shrugged, as if embarrassed he had ever made a scene. In fact, the man could hardly believe that these experts and resources were available, helping him find and rescue his younger self. For therapy, he thought, it was ingenious, the kind of thing he might actually pay for.

“Totally,” the man said. “It’s just… you know, there are no windows and… anyway, I think I heard something.”

“You heard something?”

“A sound.”

“What kind of sound?”

“Nothing specific. The sound of—” The man stopped. “That recording you played. It was like that. A kind of whisper.”

The psychologist and the architect exchanged a quick look.

“From behind this door?” the architect said, rotating his hand and zooming-in on the crawlspace. The model expanded in space, filling the entire dome.

“No, from the hallway upstairs. I went upstairs.”

What the man didn’t say was that, when he did so, the entire dream had changed around him; what had been a warehouse had become the upstairs of his own childhood home. He had been walking down the hall toward his own bedroom.

“You should have told us,” the psychologist replied. “How many doors did you see?”

“Four,” he said, describing his old house. There was his room, his parents’ room, the bathroom, his brother’s.

“That’s… that’s not right,” the architect replied. The psychologist shot him a look. “I mean, the kinds of numbers we see—the symbols—are… they’re usually in groups of twelve. It’s standard dream symbolism. Jungian stuff.” He faltered, looked down. “All doors represent something,” the architect continued, shifting in his seat. “Every wall, every window. Are you sure there weren’t twelve doors upstairs?”

“I don’t think so,” the man replied. “I saw four. I’m sorry.”

He caught the psychologist briefly shaking her head.

“The challenge here is about resolution,” the architect insisted. “We need to get to a very high degree of dream resolution. Does that make sense?”

“Dream resolution,” the man repeated.

“Yes. Now, we are confident there are twelve doors. Which door leads to the boy?”

*

The architect came alone this time. The psychologist, he said, was still busy with another participant; “something came up” was the only explanation he offered.

The man ignored her absence. The truth was, he knew absolutely now that he was looking for himself—and he was close, he thought, perhaps just one door away. His dreams now took place almost entirely in his childhood home, and he thought the architect would be pleased by this. He thought that was the entire point of the study.

To rescue the boy.

As the man’s descriptions changed, however, the architect began to look uncomfortable. He seemed hesitant even to continue and eventually put his laptop down, no longer typing.

“What’s up?” the man asked.

The architect studied the model hovering above them. He rotated it. Opened it. Closed it.

“Are you sure the building changed like this?” the architect said. “It changed—but the boy was still inside? You’re positive?”

“Is that bad?”

“We can’t afford to look in the wrong place. Especially not now. Did this warehouse—this office—really become a suburban hou—”

“Yes,” the man interrupted him. “It did. It’s the house I grew up in. And I dreamt about a different room this time—my old room. I opened the door and went in. There was a boy in it.” The man felt triumphant; he had solved the puzzle. “The boy was me.”

The man had been expecting validation, but the architect glanced down as his laptop as if to avoid eye contact. After a few seconds, the architect spoke. “You should be open to the possibility that the boy is not you,” he said, “and that there might be something else going on. I mean, your dreams might mean something else.”

This, the man thought, was immensely frustrating. He was on the verge of a breakthrough, of connecting with his younger self—which seemed to be the entire point of the damn study—yet the only people he could talk to about it didn’t care. In fact, they seemed actively disappointed. Worse, it was like they would have been on his side—they would have helped the man find himself—but only if he described the right building.

The disassociated urgency of the last few days must have gotten to him, because the man’s feelings flipped in an instant, from enthusiasm to sheer petulance.

“We can’t have your conscious mind interfering with the study like this,” the architect continued. “You have to let go of that. Trust the dream. Don’t try to shape it. Follow; don’t lead. Can you do that?”

“You guys are too hung up on the architecture,” the man muttered.

“Excuse me?”

“You’re too fixated on the building,” the man said, speaking up. “I thought this was about my dreams. If we’re going to talk about my dreams, let’s talk about the building that’s actually in my dreams. Not whatever building you want me to study.”

The man wanted to tell the architect about his old bedroom, about the house where he had lived until he was ten years old, about reading books by flashlight at night and dreaming of… well, a life that was nearly the opposite of his own. A life unlike anything he led today. He had lost sight of that version of himself. He was finding it again.

And this dream therapy, the man wanted to say, had been the perfect intervention. He had actually wanted to say thanks. Thanks for reminding me of the boy I used to be. Thanks for—

“Let’s agree that you’ve made progress,” the architect said, “and we’re almost there. But let’s be open-minded about what these dreams might be, not distracted by—”

“Distracted?”

“Distracted. What if I said this is an ideal chance to prove something? That it’s our chance to demonstrate something completely new? But we can only do it if you find the boy.”

The man, thinking this must be part of the test, pictured his younger self huddled in his room near the window, looking out at the trees and stars, dreaming of a future that had yet to come to pass.

“ I am the boy,” the man said. “That’s the entire purpose of this study, right? I am the boy.”

*

It seemed far too soon, just another glitch, but the lights began to blueshift.

The man got up after what felt like twenty minutes’ sleep and stumbled into the front room, one hand hiding his eyes. The door lock buzzed open and a woman walked in.

“We found him,” the guide said.

The man hadn’t seen her in days. In fact, he’d forgotten she existed. What happened to the architect, to the psychologist?

“It was someone who started last night,” the guide continued. She seemed elated. “Her dreams worked. We found him.”

The man didn’t understand. “Found who?”

“The boy.”

He had no idea what she was talking about. “There was another boy?” He thought back to those dreams about himself, trapped in his old family house. Wasn’t he the boy?

It occurred to the man then that he might still be dreaming, but the room around them continued to blueshift. That color alone at this point, would jolt him wide awake, if only due to habit.

The guide looked at him, her expression changing, as if realizing she had said too much.

“Your time is up,” she said, smile fading. “Just some final paperwork and you’re good to go.”

Seeing the man’s confusion, the guide tried a different approach. “How did you dream?”

*

The man spent the rest of the day catching up on texts and email after five days away from his device, then he met up with a friend for a quick drink. Which became two drinks, then three.

Then he was back in his apartment, looking around at its anticlimactically mundane amenities. No dome, no 3D laser projection, not even a king-size bed. He turned on his TV and showered, opening a bottle of beer he had forgotten was in the fridge and sipping it, naked, staring around at his apartment as if seeing it for the first time. Street noises blared in from outside and the windows were bright with the spectacle of shops, cars, and buildings.

The man lay down. The market across the street had closed for the night; its afterhours lights stained the man’s curtains a deep, wine-like red, making him yawn. It felt like the study all over again, the room redshifting, his mind drifting, everything slow—

He opened his eyes.

“—found the boy in a warehouse near the stadium,” a voice on the TV said, “where he had been held for nearly a week. His abductor was taken into custody without incident.”

Found a boy?

“Police say they launched the raid this morning after receiving an anonymous tip—”

On screen, the man saw, was a building he recognized. No, he thought. Its front door. Its windows. Its roofline. No fucking way.

“—in an unexpected end to a kidnapping saga that had local police and the FBI scrambling—”

It was the same goddamned building.

The man lay there in the red half-light of his room, dumbfounded, watching as a camera crew went inside the building. Someone offscreen began interviewing a cop, a black cop with a handlebar mustache— that mustache—in front of a door with three locks in a row, top to bottom, one, two, three—

“We’re just happy we can bring the boy home to see his parents,” the cop said. “That’s all that matters now. We tried new techniques—”

But the man was just staring now, his eyes unfocused, the camera centered on a dark staircase, the hall at its top lined with black doors. Twelve doors.

The man switched off the TV. He lay there in bed, watching lights move across the ceiling.

He couldn’t sleep.

from VICE https://ift.tt/34gbLrC

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment