Dead Cells entered early access more than two years ago, and it’s still being updated with new weapons, enemies, areas. This wasn’t the plan. Dead Cells was not supposed to go on for years. But the massive success o f Dead Cells caught developer Motion Twin by surprise, and so this past August, they made a big change. Dead Cells would live on, but no longer be developed by Motion Twin. Instead, the future of Dead Cells—future game updates, potential sequels, whatever—would be handled by a new studio called Evil Empire.

Evil Empire isn’t a bunch of newbies, but made up of a handful of Motion Twin employees who wanted to continue working on Dead Cells, while Motion Twin itself moved on. It’s being led by Motion Twin’s now-former head of marketing, Steve Filby, and despite being spun-off from Motion Twin, it’s still subject to their approval; Motion Twin weighs-in on and signs off on their creative decisions when it comes to Dead Cells.

Critically, though, Evil Empire is not something Motion Twin was and remains: a co-op.

“There's a lot of reasons for that, though the main one is directly related to scaling,” said Filby in a recent interview with me about Evil Empire’s decision making. “While I am literally having heart palpitations thinking about all the work, the aim of the Evil Empire team has always been to grow and to be able to go past the 8-10 person limit of the Motion Twin model.”

A co-op pushes back on traditional corporate structures, in video game companies or otherwise, in which some are paid more than others, some have financial investment in the studio that could later pay off with a hit (or if the company is sold) and others do not. In broad strokes, a co-op tries to flatten things and put everyone on the same playing field, including economically. The vast, vast majority of video game companies are not co-ops. It’s a rare concept precisely because it runs counter to society’s traditional understandings of power dynamics.

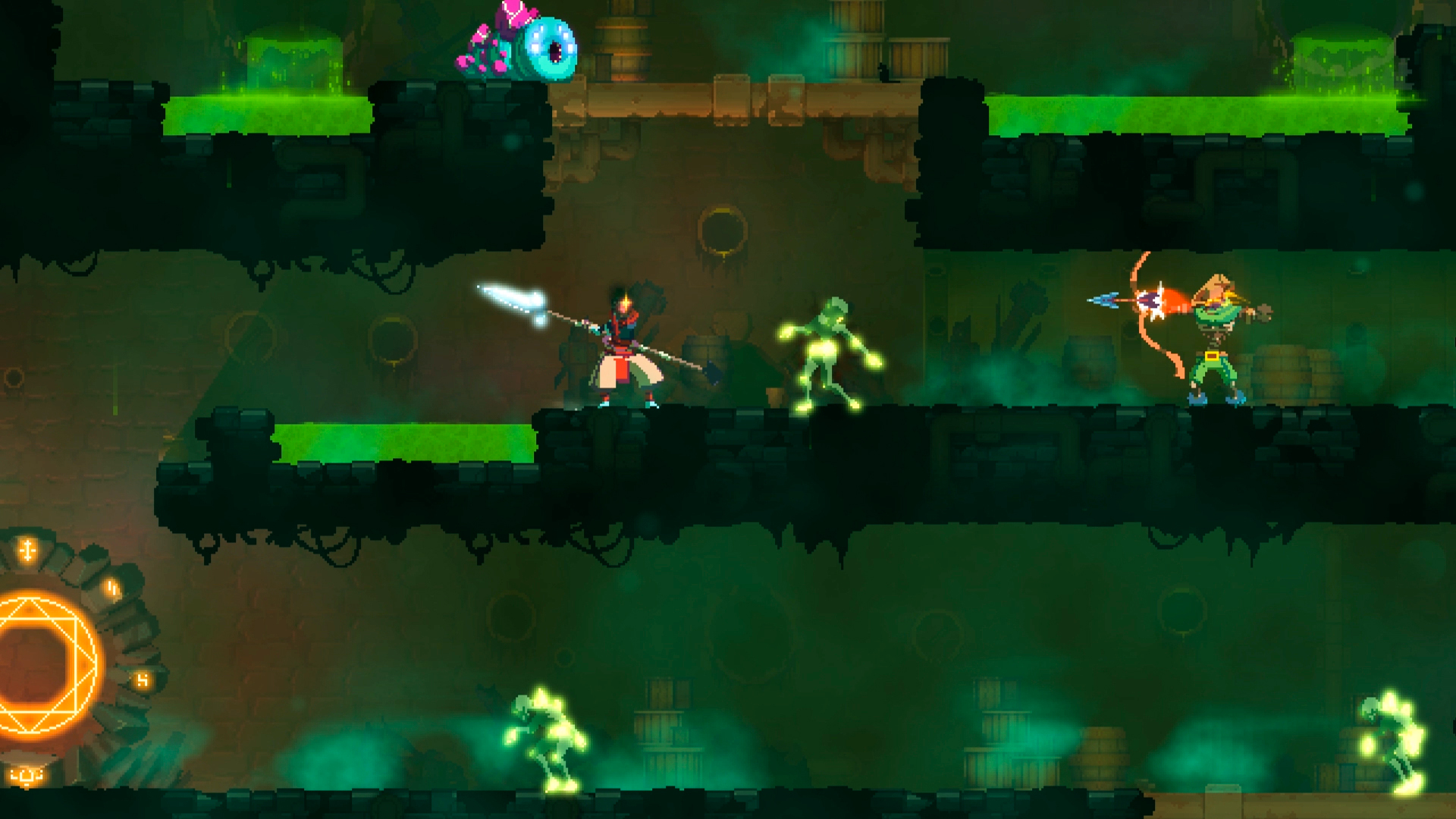

Motion Twin was a successful developer before Dead Cells, a studio with a string of hit web games, but the brilliant action game mashing up Castlevania with roguelikes is what injected Motion Twin into the public consciousness. Making a hit game is hard but not itself unique, but Motion Twin, as a company, definitely was; as profiled by Kotaku in 2018, Motion Twin was built as a co-op, which meant all its 11 developers shared equal status and equal pay.

“We actually just use a super basic formula: if a project finds success, people are basically paid more in bonuses, and everyone is paid the absolute same way,” Motion Twin game designer Sébastien Bénard told Kotaku at the time, and who still remains at Motion Twin. “The devs and the artists are paid the same amount of money, and people like me who have been here for 17 years are paid the same amount as people who were recruited last year.”

Filby told me the co-op model came with specific challenges Evil Empires hopes to address.

“The co-op model comes with a bunch of constraints!” he said. “It's not all rainbows and fists in the air. There's a stack of work, emotional costs and a whole lot more that's hidden below the surface. It's definitely not for the faint-hearted or someone looking for a cruisy 9-5. When you have to defend and justify your every idea to each and every member of the team, you have to be very motivated.”

Filby pointed towards the concept of “permanent battles,” where Motion Twin’s zero hierarchy model, in which bosses are made irrelevant and everyone has a voice in a creative decisions regardless of their expertise, as “a game of persuasion” and “really taxing.” He pointed towards moments, without specifics, where parts of the team would be “blindsided” when a decision that had once been a “yes” would become a “no” for “uncertain reasons.”

“It sucks when you have to give people a crash course in graphic design, especially when those people are programmers incapable of drawing a stick figure,” said Filby. “At Motion Twin everyone can criticize everything anyone does, which leads to some bizarre moments. We are trying to centralize these moments with regular playtesting and dedicated feedback sessions instead of the perma-siege that can happen at Motion Twin.”

Despite this, he noted, “none of the above are reason not to [make a co-op],” and said Evil Empire is still looking towards the co-op model to establish its own organizational founding.

Some of the changes are huge, though. Evil Empire wants to get much bigger, and Filby argued it requires getting rid of some structural elements, like paying everyone the same.

'The co-op model comes with a bunch of constraints! It's not all rainbows and fists in the air. There's a stack of work, emotional costs and a whole lot more that's hidden below the surface.'

“We reward talent and pay people who are extremely good at their jobs more, which makes it easier for us to recruit compared to Motion Twin,” said Filby, “where you sometimes have awkward conversations with people: ‘Yeah, your base salary will be a third of what you could get in London. But if we blow it out of the water, you’ll be rolling in it!’ can be a tough sell for seniors [workers with lots of professional experience] with families who need stability.”

It also means not every employee at Evil Empire has a guaranteed stake in the studio, a process Filby called “selective.” The plan going forward is “a system where everyone who works on a project gets a cut,” but the details haven’t been fully worked out, and Filby said it was “cautious about making sure we’ve got enough reserves to build the next game post Dead Cells, just in case our collaboration with Motion Twin ends sooner than expected.”

That last line seems to suggest the collaboration may not be permanent.

In France, where Motion Twin is located, the studio is a “SCOP,” or Société coopérative, a relatively recent phenomenon. This means, Filby explained, that Motion Twin is legally required to pass on a specific percentage of its earnings to workers, and traditionally, Motion Twin has passed on most of its profits to its workers. The result is a studio that doesn’t have a “war chest” of money, in case things go awry, but its workers end up personally enriched; when Motion Twin makes money, said Filby, “95 percent” becomes salaries and bonuses.

“The members of Motion Twin know they work better with a fire under their asses,” said Filby. “Every rut they've ever had was caused by an abundance of comfort, so they like to live dangerously to stay hungry.”

Because of the way Motion Twin is structured, it pays a lot of taxes “for the awesomeness of the French welfare state,” as Filby put it. That’s all on purpose. But Evil Empire wants to be more conservative. A percentage of Evil Empire’s eventual revenue will get paid out at certain milestones, with money given out based on “posts, seniority, and time with the company.” It’s in line with the way companies, inside and outside games, distribute cash.

And unlike Motion Twin, Evil Empire will, in fact, have a “war chest” of sorts.

“People will run themselves into the ground if the team isn't vigilant in ensuring that crunch and burnout aren't kept in control,” he said, “but it's also stressful to not know where your next paycheck will come from (that’s how we were right before the launch of Dead Cells).”

Additionally, Evil Empire has ambitions to be a much bigger company.

Over the years, Motion Twin fluctuated in size, but eventually settled between eight and 10 employees because it was a size the structure could handle. That number is in line with Canadian studio KO_OP, who have also modeled themselves after a co-op for many years.

But having less than a dozen employees means there’s only so much work to go around, which means the scope of whatever game the team is going to design will also be limited. These are by design, of course; it would be challenging to keep equity among a very large studio with dozens or hundreds of workers. By keeping teams small, it’s more manageable to ensure the notion of equity remains in place. The limited scope is a successful byproduct.

These are, all told, significant changes, one that brings Evil Empire more in line with the rest of the video game industry. It’ll be a studio, by definition, with less equity and a different distribution of power. That’s exactly the point. Evil Empire is a very different company than Motion Twin, even if it shares some employees and a shared appreciation for Dead Cells.

Whether these changes impact the kinds of games Evil Empire makes, for better or worse, remains to be seen. That said, it’s a little ominous when said changes, a shift from worker equality to worker inequality, come under the guise of a studio calling itself “Evil Empire.”

“We are conscious of the fact that we're competing with other organizations all over the world that have all kinds of comparative advantages, but we're also realistic about respecting ourselves,” said Filby. “This means that there are several core things that Motion Twin does as a co-op that we can reproduce in any company structure while still remaining a company with, at the end of the day, a profit motive.”

Follow Patrick on Twitter. If you know a game developer structuring themselves in an interesting way, his email is patrick.klepek@vice.com. He's also available privately on Signal (224-707-1561).

from VICE https://ift.tt/36iH8nd

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment