This article appears in VICE Magazine's 2019 Profiles Issue. This edition looks to the future by zeroing in on the underrecognized writers, scientists, musicians, critics, and more that will shape our world next year. They are "the Other 2020" to watch. Click HERE to subscribe to the print edition.

It was around two in the morning when Jessa Jones began to feel like the blood-soaked iPhone in her possession was a lost cause. The microsolderer had spent hours holed up in her repair shop, painstakingly cleaning and replacing rice-size chips on the phone’s logic board and fixing a tiny electrical problem affecting its power button. But when she pressed that button, the device still wouldn’t turn on.

“I was exhausted, and I was feeling kinda hopeless about this phone,” Jones said. “I was pretty close to saying this is beyond what I can recover.”

Jones is a world-renowned phone fixer, but this was far from an ordinary repair job. The device she was working on that night in May of 2017 belonged to Srinivas Kuchibhotla, a 32-year-old Indian man who was fatally shot earlier that year in a bar in Olathe, Kansas, a horrific hate crime that drew national attention. The phone was likely in Kuchibhotla’s pocket when Adam Purinton, a white man, began hurling racial slurs at him and another Indian national named Alok Madasani, shouting “Get out of my country!” before opening fire. (Madasani was injured but survived.) By the time the police recovered the device from Kuchibhotla’s body, it was drenched in his blood.

Several months later, Kuchibhotla’s wife, Sunayana Dumala, took the phone to a local repair shop, desperate to boot it up so she could access some final snapshots of her husband’s life. A technician, Dumala says, took one look at the device and knew he wouldn’t be able to help. But he told her that Jones, who runs a gadget repair shop in the tiny upstate New York town of Honeoye Falls, just might.

Dumala shipped the phone off to New York almost immediately.

Our smartphones are practically extensions of our bodies these days, but we treat them as if they’re disposable. We trade them in when the screen gets cracked; we discard last year’s model for that shiny new one with slightly better specs or a new selfie camera. We do this, in part, because the companies that make our phones frequently tell us they cannot be fixed: The cost is too high, the internal circuitry too complex for our simple minds to fathom. Instead of being encouraged to try, we’re told to replace.

Jones will tell you that’s bullshit.

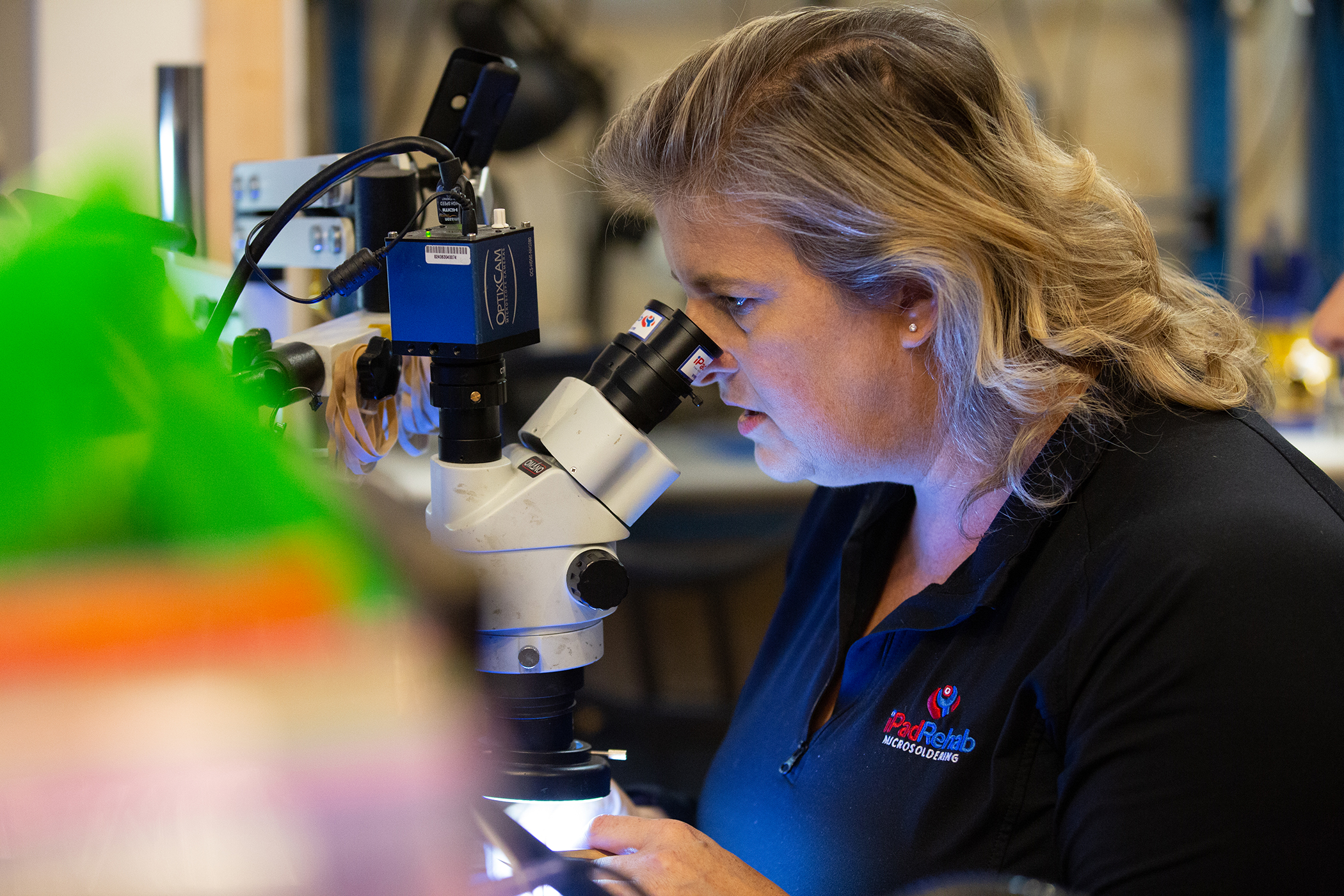

A mother of four with a PhD in molecular genetics, Jones has become an unlikely leader in a growing community of microsolderers. These are fixers who aren’t just swapping cracked screens and dead batteries, but who are more like physicians, diagnosing and repairing tiny electrical problems on the motherboard (or logic board, as Apple calls it). This is the beating heart of your device, containing chips and circuitry responsible for many essential functions. In a matter of minutes, a skilled microsolderer can fix a short circuit on an iPhone that fell in the bathtub, and by doing so she can bring the device back from the dead—something Apple frequently tells customers is impossible.

But Jones doesn’t limit herself to simple short circuits. She’ll revive phones that have been through hell: phones that were run over by a car; recovered from the wreckage of a crashed airplane; bathed in the blood of a dead owner. She goes to great lengths to do so not because these devices will necessarily be used again, but because someone’s last memories are locked away inside. In the case of iPhones, which have had their data encrypted since the release of iOS 8, the only way to recover those memories is to boot up the phone and enter the passcode.

For those who’ve lost precious photos, videos, or messages, getting those digital mementos can be a profound experience.

“People cry about it, all the time,” said Joe Ham, a microsolderer whose Washington State repair shop, Gadget Genie, is one of the few shops that can do complex data recovery jobs from Apple devices. “They say, I really need this, I’ve taken it to three other shops, you’re my only chance.” Ham, who’s been fixing gadgets his whole life, credited Jones with giving him the confidence to launch a microsoldering business after he flew across the country to learn from her.

Jones didn’t set out to fix tiny computer circuits for a living. But after she left her job teaching college biology to become a stay-at-home mom, she had some time on her hands. When her sons started cracking iPad screens, Jones watched online repair videos and learned how to replace them. When her then-toddler-age twin girls dropped her iPhone 4S in the toilet, Jones took the toilet outside, sledgehammered it open, retrieved the phone, and decided to fix it.

That decision would change her life.

After she swapped the phone’s battery and charge port, the phone still wouldn’t hold a charge. Eventually “it became clear that it was a motherboard problem,” Jones said. “And it just seemed like it had to be a solvable problem.”

Jones purchased soldering equipment and a microscope and began tinkering with other dead devices. It took over two years and countless hours on repair forums, but eventually, she got the toilet phone working again. By the time she did, Jones was pretty good at repairing lots of common phone problems and had launched MommyFixit, a mail-in repair service she operated out of her dining room. Soon, Jones was drafting other stay-at-home moms to help her run the business.

“Moms are super capable,” Jones said. “And they’re really good at fixing phones.”

In 2015, Jones, along with fellow mom-fixers Sunday Thomson and Christy Dryden and another microsolderer named Mark Shaffer, moved into a derelict shop at the corner of downtown Honeoye Falls’ lone stoplight intersection and rebranded themselves as iPad Rehab. They’ve been there ever since, using their specialized skills to fix smartphones and tablets from all over the world. Once a month, Jones teaches a practical board repair class out of the shop, and in doing so has spread her knowledge to hundreds of other fixers. She teaches far more on her repair-focused YouTube channel, which has amassed 130,000 subscribers since its launch around the start of 2015.

“She doesn’t just fix stuff, she teaches others how to fix stuff,” said Gay Gordon-Burne, the executive director of the grassroots trade organization the Repair Association. “Which means there’s more skill out there than there ever was before.”

Jones isn’t just a teacher, but a voice for the community she’s helped build. She’s a vocal proponent of right-to-repair, the simple idea that if you own a device, you should be allowed to fix it. It’s a stance that frequently puts Jones at odds with Apple, a company that has become notorious for its anti-repair stances. For years, it refused to sell parts and share information with unauthorized repair shops (and authorized shops are prohibited from doing any of the logic board repairs Jones offers), forcing independent and DIY fixers to rely on aftermarket parts that can vary in quality and, in the case of microsolderers, on board schematics that were leaked to the internet. As Apple lobbies against right-to-repair legislation and repeatedly introduces updates aimed at spooking its customers out of attempting repairs at home, Jones fights back, advocating at state houses, testifying as an expert witness in iPhone repair cases, and repeatedly calling the company out on her YouTube channel when she feels Apple is spreading misinformation about what can be fixed.

Data recovery is a common example. Jones said she frequently gets customers who’ve been told by an Apple employee that the data on their water-damaged phone or tablet is unrecoverable. Or the customer may have been directed to DriveSavers, a company that originally specialized in hard-drive data recovery, where customers sometimes are quoted upwards of $1,000 to get photos off iPhones. (When I called DriveSavers’ customer service line and asked how much it would cost to recover photos and videos from a water-damaged iPhone, a representative told me it would be in the $700 to $1,900 range and “probably in the upper third.”) Jones charges $300 for a basic data recovery job.

“How many people were told ‘Kiss those pictures goodbye, there’s nothing you can do’?” Jones said. “I don’t know, but it’s a huge number, and that’s really sad.”

“This is exactly why right-to-repair exists,” said Nathan Proctor, who heads up the U.S. Public Interest Research Group’s Right to Repair campaign. “So that there can exist a market for repair outside of what manufacturers want to offer people.”

When I reached out to Apple to ask what sort of help it could offer a customer who wanted to recover data from a dead device, a spokesperson sent me a list of links to Apple support pages detailing how to back up your working iPhone and to Apple repair services (none of which mentioned data recovery). Apple declined to comment on record about independent repair shops that offer data recovery services.

Jones has a quick smile and a matter-of-fact demeanor that puts you at ease right away. Her shop is equally inviting; the front is styled like a parlor room with a dining table, a thrift store couch, and an array of beverage options available for clients. A painting of Mona Lisa holding an iPad, done by Jones’ husband, hangs near the entrance. When I visited on a cold, rain-soaked October morning, I was offered a cup of hot tea and escorted to the back. There, the homemaker’s façade gave way to a maverick’s laboratory of microscopes, soldering stations, multimeters, and DC power supplies. At every workbench, phones and tablets sat in various stages of dissection.

Jones had pulled together some case studies for my visit: phones that were sent to the shop for data recovery after they died. There was an iPhone that a woman in California accidentally ran through the washing machine for five minutes. The phone was dead, and she had lost all her kids’ baby pictures. An iPhone from Nebraska had also taken a bath and died, taking out a year’s worth of family photos with it.

As we opened up the phones to look at their logic boards, Jones talked me through the process of diagnosis and repair. She did so with the clarity of a doctor telling a patient about their latest lab results and the enthusiasm of a high school science teacher. “This is very much like science,” Jones said. “It’s troubleshooting, pattern recognition, and experiments. It’s also fast and doesn’t take months. So that’s why I love it.”

Some of the phones we dissected had neat and tidy solutions, like an iPhone 6S that had a single short circuit preventing it from powering on. Having seen this problem many times before, Jones immediately zeroed in on the sand-grain-size capacitor that was causing trouble, tweezed it out, and booted up the phone. Other cases weren’t so straightforward. We examined a water-damaged iPhone that had important chips stripped from its logic board, meaning somebody had been working on it before it was sent in. Jones spent about an hour attempting to wind the clock backward from that prior repair attempt, but eventually concluded the phone likely wouldn’t be recoverable.

There are so many data recovery jobs with similar stories—water damage or a bad drop; lost pictures of a newborn baby or grandma’s birthday—that they blur together in Jones’ mind. But iPad Rehab also receives devices from parents whose child committed suicide; from families who lost a loved one in a tragic accident. Working to restore these phones can be painful, but they’re also some of the most rewarding jobs Jones gets.

A few years back, a Rochester native named Peter Lovenheim brought in a phone that belonged to his sister, Jane Glazer. The device had been recovered by divers at the bottom of the Caribbean Sea, where Glazer and her husband’s private plane crashed in September 2014, killing them both. Lovenheim had sent the phone to a different repair shop first, which told him it was impossible to recover. Another company he called said to not even bother sending it in. When he discovered Jones’ shop, based locally for him, he drove over and dropped off the phone.

Within a couple of days, he said, her team had recovered the data.

“It was astounding,” Lovenheim said. “She was able to give us scores of photos.” One of the final photos ever taken of his sister is now sitting framed on a dresser in his house.

Last year Jones’ shop received another plane crash case. In late February of 2018, Bill Kaupp, a 64-year-old private pilot from Alberta, took a small aircraft out for a spin along with his 28-year-old son, his best friend, and his son’s best friend. It was supposed to be a quick test flight, but something went horribly wrong, and the plane crashed just west of the Colorado border in Utah. Nobody on board survived.

Several days later, two iPads that Kaupp used for navigation were discovered cracked, smeared with dirt, and buried in snow amid the wreckage. It seemed “pointless” to try to fix them, said Lindsay Magill, Kaupp’s 38-year-old daughter. But she tried anyway. One of the tablets turned out to be a lost cause—the memory chip was damaged. But Jones’ team was able to recover the other, which contained photos and videos of Kaupp with his grandchildren in Montana just days before the accident.

“I can’t express my gratitude enough to Jessa,” Magill said. “There’s no replacing the videos and pictures she recovered for us. And it’s something his grandchildren will have for the rest of their lives.”

Every phone that Jones brings back from the dead shines a little more light into a life someone wants to remember. For Jones herself, Kuchibhotla’s story may be the most unforgettable.

Born in Hyderabad, India, Srinivas Kuchibhotla came to America for a master’s in electrical engineering at the University of Texas, El Paso. There, he started a long-distance relationship with Sunayana Dumala, who was from the same hometown.

“For me he was the perfect guy,” Dumala said. “He would add humor to a discussion when it was required. He would be the most mature guy in the group when it comes to giving opinions. He was caring, humble, always respectful of others.”

In 2012, the two got married in India and moved in together in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where Kuchibhotla worked as an engineer at an avionics company. About a year later, Kuchibhotla was offered a job at Garmin, and so the couple packed up and moved to Olathe, a suburb of Kansas City where the company is headquartered. Kuchibhotla quickly became part of the community, joining a cricket league and playing pool with his co-workers at happy hours.The couple bought a lot and built a house, where they eventually planned to raise their kids.

That dream ended when Kuchibhotla’s life was taken at a bar on the night of February 22, 2017.

When Jones received the phone that had been with Kuchibhotla in his final moments, she was hit with a torrent of emotion. There was no escaping the fact that this device was only in her hands because of an act of brutal violence.

“I can remember a thick, heavy feeling from the history of that phone, that just filled the room,” Jones said. “This was filled with a human being’s blood from the night that he died. And it was really hard not to just burst into tears.”

The phone was so drenched with blood that Jones had to spend several hours cleaning the logic board in an ultrasonic bath before she could work on it. Once she’d gotten it as clean as she could, she sat down at her workbench, turned on a livestream, and began examining the phone under the microscope.

Jones removed chip after chip from the logic board and discovered that every one was still caked with blood on the other side. After she cleaned and replaced a number of critical chips and spent a while troubleshooting a power issue on a critical line, the phone still wouldn’t turn on. It was well past midnight, and Jones was nearing the end of her rope.

Every phone that Jones brings back from the dead shines a little more light into a life someone wants to remember.

About to give up, she decided to try one last thing. Jones had been attempting to boot up the phone using the power button, but an iPhone can also be prompted to boot by connecting it to a USB device. So she did that. Somewhat miraculously, the phone started to boot. When Jones connected a screen, it was responsive to touch, meaning a passcode could be entered. She had a path to its data.

“It was just really amazing,” Jones said. “I really had been very close to actually saying it’s not responsive, and I’ve replaced this whole board.”

The next day, Jones and Thomson together called Dumala to tell her they’d restored the phone and extracted all the photos. “We were in tears, she was in tears,” Jones said. “You couldn’t help it. And she was just, at the time, super grateful [to have] this little win in this horrible situation.”

“The way they handled it just spoke volumes about them,” Dumala said. “How they take it personally. I think, no wonder iPad Rehab is run by women, because we know the value of relationships and memories. It’s not just data. It’s the human value.”

Dumala still lives in the house she and Kuchibhotla built. Because she was a dependent on her husband’s visa, she had to apply for a new one after he was killed, and in doing so was bumped to the back of India’s astronomically long immigration line. All the years she spent waiting to become a citizen with her husband were lost; she now has to start over.

But Kansas has become Dumala’s home, and she’s not leaving. When she’s not working, she advocates for immigration reform. She started a Facebook page, Forever Welcome, to honor her husband’s memory, share immigrant stories with her community, and spread a message of unity and acceptance. She’s planning to turn it into a foundation.

The phone that Jones repaired sits on Kuchibhotla’s nightstand.

from VICE https://ift.tt/35aAEp8

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment