This article appears in VICE Magazine's 2019 Profiles Issue. This edition looks to the future by zeroing in on the underrecognized writers, scientists, musicians, critics, and more that will shape our world next year. They are "the Other 2020" to watch. Click HERE to subscribe to the print edition.

Like so many Memphis stories, this one starts with a legendary Black musician. Don Bryant is one of the city’s quintessential homegrown geniuses, a savant who sold his first song while still a teenager in 1960. He would go on to become one of Hi Records’ house talents in the label’s heyday, releasing one solo album in 1969 and composing hits for O.V. Wright, Otis Clay, and Ann Peebles, with whom he wrote “I Can’t Stand the Rain” in 1973. The two were married the following year, because what else can you do after making something so perfect together?

By the time Fat Possum Records approached Bryant, in 2016, Hi hadn’t been an active label since the late 1970s, and Bryant hadn’t written or released any secular music under his own name for nearly half a century. The Oxford, Mississippi, label has cultivated and reissued Southern blues and soul artists since 1991, and Don’t Give Up On Love, the album released in 2017, featured Bryant in a typical Fat Possum retro setting: close-miked, unadorned, surrounded by tasteful session musicians playing live in the room.

Producer Bruce Watson, a Fat Possum executive since 1994, was struck by two of those musicians in particular. Courtney and Chris Barnes were both less than half Bryant’s age, but they sang behind him with effortless poise.

“I got goose bumps listening to them,” Watson recalls. “We started using them on everything.”

The Barnes boys are native Memphians and full-time musicians with experience across all the city’s defining styles. Older brother Chris has sung behind rappers 8Ball & MJG and with Larry Dodson of Stax legends the Bar-Kays, and the pair also leads their own rock band, Black Cream. But like Bryant—and like most of Black Memphis—their deepest roots are in the church, in gospel. Watson heard their harmonies, honed since childhood by their parents and their equally musical brother and sister, and he thought of the Staple Singers. That kind of country gospel-soul isn’t the genre’s typical contemporary format, which hews toward a slicker, more heavily produced sound indebted to Kirk Franklin, among others. But it was a natural fit for a label that made worldwide draws out of raw Mississippi bluesmen like Junior Kimbrough and R.L. Burnside.

In September 2019, Watson’s vision finally came to fruition. Nobody’s Fault but My Own is the debut album by the newly christened Sensational Barnes Brothers, and the first original release on Bible & Tire, Watson’s new gospel imprint. On the one hand, Watson is simply attempting to do for gospel what Fat Possum did for Mississippi blues—to introduce it to the eager Americana audience that values rough-hewn authenticity and overlooked folkways. But his task is perhaps even more fraught this time around: That audience is largely white, like Watson himself, and not necessarily receptive to the explicit proselytizing of Black church music.

That balance of commercial optimism and preacherly purpose—one might say sacred and profane—is evident in the Barneses themselves. Asked if their primary goal is to sell records or save souls, the brothers hedge. “Whether you believe or not, everyone has a connection to God,” says Courtney. “God is everywhere, and I do want people to come close to belief in God and Jesus.”

Chris is still adjusting to the idea that this music might be commercial at all. After a lifetime of singing it with family and on Sunday mornings, he said, “it’s surreal. It’s new for us to have a white guy come in and take an interest. Bruce is a businessman. I had no idea there were hipsters, as he calls them, who love this music. But maybe it’s time for a new thing.”

On September 20, the release day for Nobody’s Fault but My Own, Watson and his team put on a concert east of downtown Memphis. The Sensational Barnes Brothers headlined, but the bill also included a handful of the city’s older gospel groups as well as Elizabeth King, whose own religious recordings from the early 1970s were being reissued by Bible & Tire the same day. The event epitomized the Fat Possum old-meets-new ethos, with the added intimacy of a genuine community who had known each other for decades.

Watson paced in a leisurely fashion through the back hallways and green room of the Crosstown Theater all day, never raising his voice or attracting attention. He’s in his mid-50s, gently grayed, and manages the rootsy label Big Legal Mess in addition to Fat Possum and Bible & Tire. But even as he corralled multiple generations of musicians and prepared for an expected crowd of hundreds, Watson never seemed stressed. While Elizabeth King sound checked with the house band, Watson stood at the side stage near the soundboard, arms crossed in a short-sleeved western shirt and black-framed rectangular glasses.

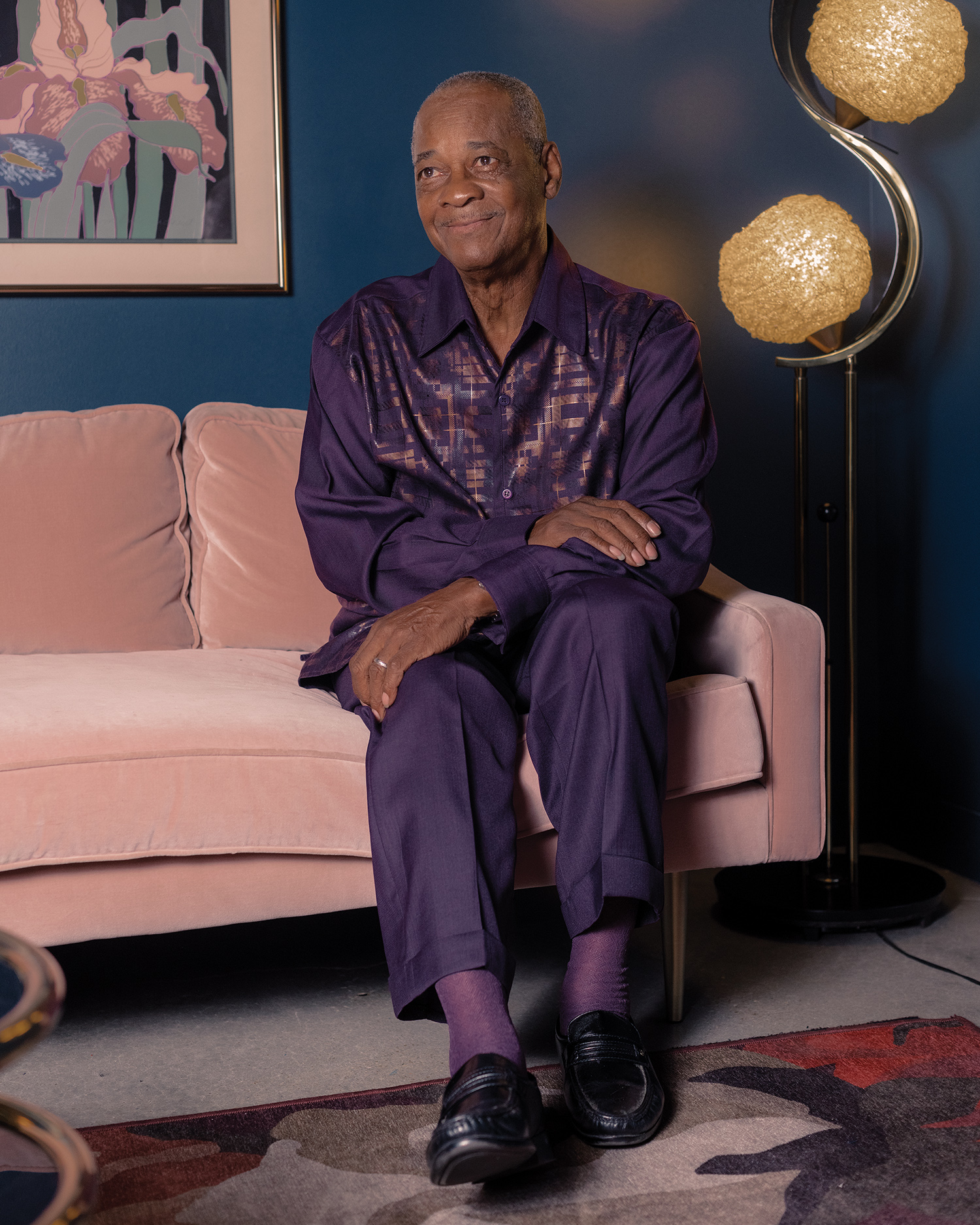

His crucial collaborator for the Bible & Tire project, Pastor Juan Shipp, arrived early to the venue as well. Pastor Shipp is Watson’s opposite in many ways, a vibrantly youthful 80-year-old Black preacher and Memphis lifer with a hype man’s unflagging energy. His button-down shirt and crisp pants were both made of purple silk, and he wore a black baseball cap emblazoned with the message jesus is my boss as he passed out gig flyers and roamed every corridor of the theater, leaving a trail of cologne scent wherever he went.

“It fell in our lap,” he said of the growth of Bible & Tire, resting momentarily on a couch backstage. “But it’s also divine.”

In the 1960s, when he wasn’t preaching or working his regular job at the post office, Pastor Shipp was a part-time DJ for the Memphis gospel station KWAM. There was a huge number of 45s from local groups to play on the air at the time, many of them recorded and released by gospel-only independent labels like Designer Records. While Shipp never doubted the talent and sincerity of artists such as the Jubilee Hummingbirds, the Mighty Blytheville Aires, and the Holy City Travelers, Designer’s recording quality didn’t serve them, especially in an era when Stax was setting new production standards on McLemore Avenue downtown.

So Pastor Shipp decided it was time to take up a fourth job. As the 70s dawned, he met a former Sun Records artist named Clyde Leopard, whose pristine but underused studio, the Tempo Recording Service, was located around the corner from the famous Beale Street corridor. With Tempo as his headquarters, Shipp founded D-Vine Spirituals, a record label for the many artists he’d gotten to know through his ministry and his radio show.

That list included an all-male octet called the Gospel Souls. Around this time, they first heard Elizabeth King sing in church, and were so taken with her alto that they asked her to join the group as their leader. Most gospel groups at the time were either single-gendered or a mixed group of multiple men and multiple women. It was rare to have a single female voice leading a chorus of men, but Elizabeth King and the Gospel Souls soon entered the D-Vine studios to cut their first 7-inch single.

King was raised in Charleston, Mississippi, and came to Memphis in 1965 a few years after marrying at 15. This was a propitious time for a young person to arrive in the city: Booker T. and the M.G.s’ “Green Onions” was soon to turn Stax into the most successful independent label in the United States, B.B. King was ascendant, and Beale Street was the literal and figurative home of legends like Furry Lewis. But the young Mrs. King stayed far away from all of it. She loved the blues but never sang it, and certainly never drank. A loyal wife and eventual mother of 15, her voice lifted only to praise God.

For her first recording session with Juan Shipp and the Gospel Souls, King fleshed out a scrap of melody that she’d heard her mother sing back in Charleston. Her arrangement, which she named “I Heard the Voice,” was effective, but Pastor Shipp felt her singing was too aggressive, “too hard,” in his telling. He approached her in the vocal booth and spoke to the pious Mrs. King as a record producer, not a minister: “Sing it like you’re making love to Jesus.”

“I Heard the Voice” became D-Vine’s first A-side single and a significant regional gospel hit. It inaugurated a decade-long run for the label, which yielded hundreds of songs by dozens of artists, many of whom came from Memphis churches. It wasn’t necessarily lucrative, however, and eventually Shipp felt that his production and personnel-management duties were keeping him from his daily ministry. D-Vine Spirituals closed in 1982, right as synthesizers and digital recording became the norm in gospel, as in secular music.

Shipp’s archives sat in storage for decades while, 70-odd miles away in Oxford, Bruce Watson and Fat Possum built a minor empire out of analog-recording fetishism. In 2014, Watson helped open a vinyl pressing plant in Memphis to serve the growing LP market, and began spending more time in the city, record-hunting as always. Fat Possum had already acquired the Hi Records catalog by that point, and soon Watson discovered Designer, which was his gateway into the voluminous history of midcentury Memphis gospel.

In 2014, Big Legal Mess released The Soul of Designer Records, a box set collecting those raw 45s that Pastor Shipp found wanting at the time. For Watson, they represented the kind of unvarnished, unheralded regional sound that he has built his career on resurrecting. When he heard Chris and Courtney Barnes, he knew he’d found the way to bring these songs into the present day. Nobody’s Fault but My Own is built entirely from the Designer catalog; the brothers hand-picked the songs that best suited their voices, their emotions, and their spirituality.

Inevitably, Watson’s obsession led him to Pastor Shipp. Watson moved to Memphis full-time in late 2014 and learned that the D-Vine catalog was sitting in a local studio, unharmed but unheard. After a few meetings, the octogenarian preacher found himself back in the record business.

“I thought I was through with this,” he said in the Sears Crosstown green room with a smile and a sigh. Shipp is now the unofficial A&R man for Bible & Tire, bringing many of his surviving artists to Watson, some of whom were performing that night. The label will release a box set of D-Vine Spirituals recordings in 2020. But the new label’s first archival release, no surprise, is Elizabeth King and the Gospel Souls: The D-Vine Spirituals Recordings, a collection of their 7-inch singles and unreleased songs that kicks off with “I Heard the Voice.” With its easy swing and doo-wop harmonies, the song is more tender than was typical in early-70s Memphis. But you can hear Shipp’s unpastorly advice in King’s breathy, pleading inflections. Her words have a clear message, but her deep feeling—her devotion—could move anyone.

With its bright lobby and plain black-box décor, the Sears Crosstown Theater is a far cry from rowdy midcentury Beale Street. The near-capacity crowd that filled its stadium seats included many of Elizabeth King’s friends and fellow congregants, but the Bible & Tire showcase was a new type of venue for King. She still sings regularly in her Baptist church, and she performed on behalf of the Coalition for Burned Churches, a nonprofit that helps congregations rebuild, until 2003. Under bright spotlights, on a wide, tall theater stage, flanked by white roots musicians? This was new territory, even if, in her words, it was “a long time coming.”

She is quiet, reserved, not given to grand statements. When Pastor Shipp called her in early 2019, asking if she wanted to go back in the studio for the first time in decades, she said only, “Yeah.” How about tomorrow? he asked, and she agreed to that as well. It was reminiscent of their old dynamic, when she would come by Tempo Studio after a full shift as a florist’s deliverywoman and uncomplainingly work late into the night to meet Shipp’s exacting musical standards.

Elizabeth King is quiet, reserved, not given to grand statements. When Pastor Shipp called her in early 2019, asking if she wanted to go back in the studio for the first time in decades, she said only, “yeah.”

As with Shipp and the Barneses, King’s Bible & Tire opportunity is both a surprise and an inevitability. She knew Chris and Courtney’s parents because of their musical connections: Their father, Calvin “Duke” Barnes, was a self-taught pianist well-known in Memphis for recording with the gospel legend Jessy Dixon, while their mother, Deborah, is a University of Memphis–trained opera singer who spent three years backing Ray Charles as a Raelette in the late 70s. King knew the couple from church, and regularly babysat Courtney and his sister.

King’s husband died years ago, and many of her children are dispersed around the country now. Bible & Tire is an exciting development, but her eye is on the sparrow, as it were.

A few hours before showtime, she was calm backstage, thinking of her mother, who only allowed religious music in the house. “The songs that she sang were personal,” she said. “If you sing gospel from your heart, you can make people think better. There’s a higher power, and we need it. If you focus on Christ, you can change things.”

For King, her religious message is inextricable from her singing style. “A lot of times, I go to church and only hear the praise themes,” she said. “I want to bring songs like ‘Precious Lord, Take My Hand’ back. If you express yourself with the classic songs, sing about your problems, you can solve them. There aren’t many people singing this way anymore.”

The concert began at 7 p.m., when a gentle, elderly man in a fine tan suit walked onstage to greet us. This was James Chambers, a 43-year veteran of local gospel station WLOK, where he currently hosts the 6 to 9 a.m. slot every weekday. It was a familiar crowd to him, and he pointed to audience members and cracked in-jokes while two toddlers played near their parents just off stage right.

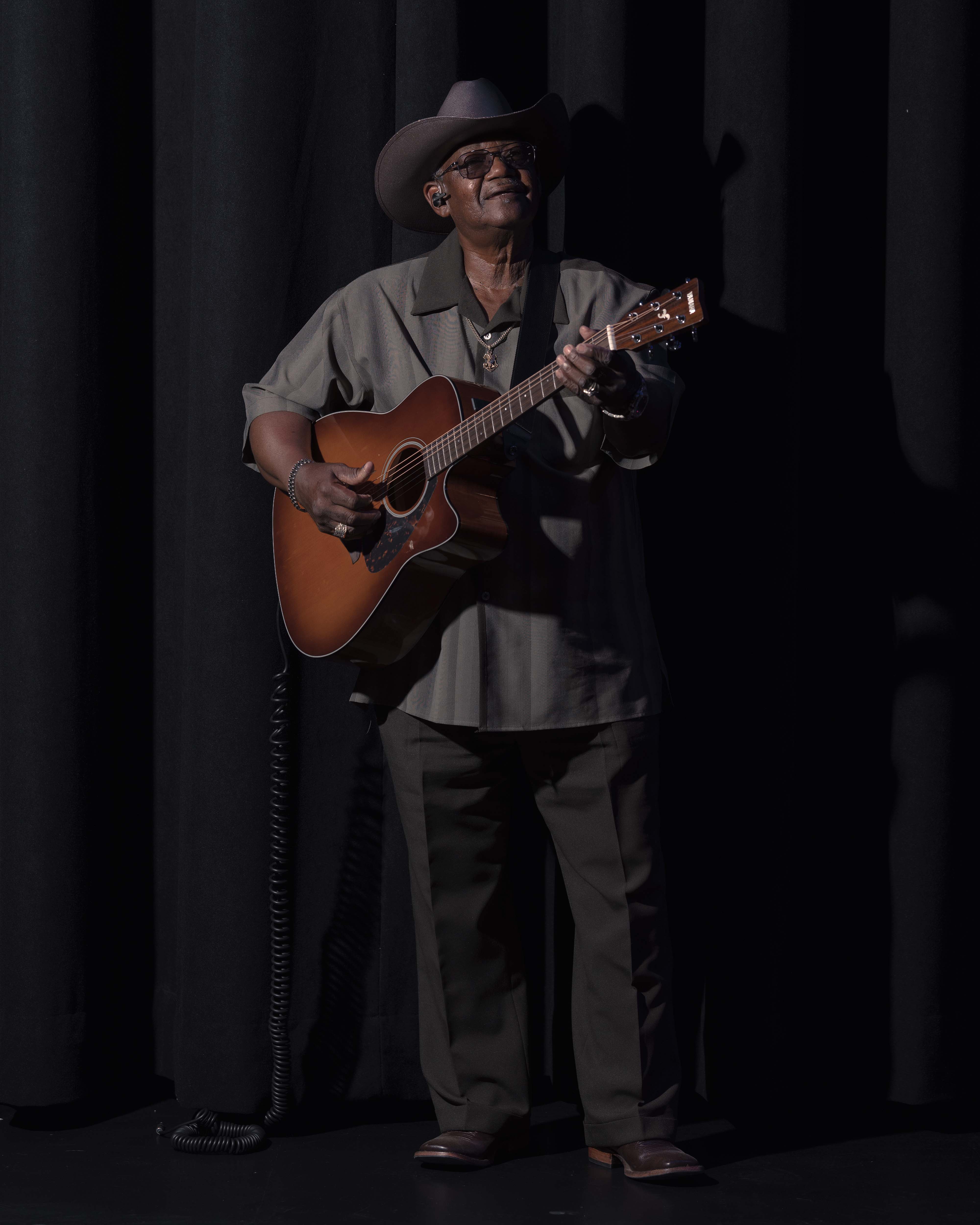

The early acts included Reverend John Wilkins, who took the stage in a black Stetson, patterned cowboy boots, and a massive watch to play solo acoustic guitar. He performed two bluesy, fingerpicked songs, including “Prodigal Son,” his father’s composition that the Rolling Stones covered on Beggar’s Banquet. Elder Ward led his mixed-gender quartet through three haunting a cappella devotionals, while the D-Vine Spiritualettes, Pastor Shipp’s onetime go-to female trio, sang without instrumentation as well. These groups’ solemn, blended sound was contrasted by Fat Possum artist Liz Brasher, who accompanied herself on electric guitar and brought the crowd to its feet with her impassioned belting.

Elizabeth King took the stage in a blinding, wide-sleeved neon pink dress and elicited a similarly raucous response. In front of drums, guitar, bass, a Hammond B3, and a trio of female backup singers, she sang for more than half an hour, largely with her eyes closed. Most of her songs started in a gentle groove and gradually built to a praiseful, chanting repetition. When fully moved, King pulled her microphone from its stand and bent over to her left, pleading and straining her powerful alto to its highest register. Under blue lights, her short, light-colored hair seemed to glow, just as the message and urgency of the material transformed this prim, churchgoing grandmother into a bright, supernatural vision.

The Sensational Barnes Brothers couldn’t match the unique spectacle of King’s revived diva-hood—no one could. But they assembled an impressive physical presence of their own, in complementary vests and gleaming shoes, alongside three male singers and the house band. The sight of five young Black men bringing this family- and community-born music into contemporary form was inspiring. Chris is the taller, broader Barnes brother, with hair and a beard that both shoot out straight. Courtney is slimmer, quieter, and more reserved, like his former babysitter, “Miss Elizabeth.” Onstage they didn’t interact so much as effortlessly coexist. Their banter was endearingly awkward when it wasn’t touchingly heartfelt, a mixture of “Who downloaded the album today, y’all?” with brief, earnest explanations of their song selections. Before the song “Let It Be Good,” which on the record features their father on vocals, they revealed that Duke Barnes died suddenly this past spring. They chose the song specifically because it echoed their father’s constant refrain that anything worth doing is worth doing well—what started as a hat-tip to an elder had become an encomium.

Gospel is so deeply entwined in black American music that there’s no reason why this sound and these singers’ recordings couldn’t appeal to the same audience that celebrates the same emotions in country, soul, rock, and hip-hop.

This is how gospel lives, after all. The power of this music, as Elizabeth King made clear, is its simplicity, its timelessness. The messages of faith, loyalty, triumph, and tragedy are the same as those of the blues, R&B, and for that matter, most pop. Gospel is so deeply entwined in Black American music—which is to say, so entwined with 20th-century pop music altogether—that there’s no reason why this sound and these singers’ recordings couldn’t appeal to the same audience that celebrates the same emotions in country, soul, rock, and hip-hop. The only difference is that these artists are supposedly singing for a purpose beyond commerce.

That’s a distinction without a difference in the world of Americana that Fat Possum has helped build. The kind of authenticity that Bruce Watson has fostered in his various labels is based in plainspoken communication and unfiltered artistic testimony; theoretically, gospel will fit right in.

Watching all night from the side of the stage, his foot occasionally stomping when the band hit a deep pocket, Watson was simultaneously the shepherd and the odd man out: a white nonbeliever, a relative newcomer to this small city’s tight-knit gospel community, and a businessman among soul-stirrers. He knows this music only as music, and loves it as such. Maybe that’s enough to help it reach the unconverted.

from VICE https://ift.tt/32X5HmL

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment