One year ago today, Michelle Cofer drove to Ferguson Elementary School in Gwinnett County, Georgia, while her husband stayed at home to watch their 3-year-old. When she got to the school, the line to vote in the 2018 midterm elections was longer than it had ever been in Rockdale, the nearby county she’d moved from two years earlier, but Cofer is a regular voter and was determined to wait it out.

Two hours later, she was at the front of the line. She’d filled out a change of address form three months earlier, but when she showed her ID, the poll worker said she wasn’t on the voter rolls. She asked if she should drive to Rockdale to vote, but another poll worker said no; instead, she could fill out a provisional ballot, which had all the same races but which would have to be approved by the board of elections later that night. Cofer had never voted provisionally, but “there was no explanation about it,” she said. “I just thought that was the option available.”

She thought she was done once she filled out the ballot and dropped it into the locked bin. “The only thing that prompted me to even inquire further was I saw a Facebook post, and somebody said, ‘If you voted on an absentee or provisional ballot, call this number to make sure your vote counts.’” Cofer called and was told that she needed to present her ID and proof of residency to the Gwinnett County Board of Elections.

The next day, a Wednesday, she made the 15-minute drive and showed the necessary documents. Again, she wasn’t in the system but was told that, since she was likely still registered in Rockdale, her vote still might count for the statewide races. On Thursday, she called the Board of Elections. On Friday, she called again. “The calls were pleasant,” she said, “but they didn’t have any information to give me.”

“If I had been instructed that perhaps your vote may count, then I would’ve just gone to Rockdale,” Cofer said. “I mean, it’s 40 minutes away. It wouldn’t have been a big deal.” Instead, after calling one more time and checking online, Cofer finally learned that her entire ballot had been rejected because it was cast out of county.

From affidavits submitted to federal court by Fair Fight Action, a nonprofit affiliated with Stacey Abrams, who narrowly lost the race for governor, it’s clear that the confusion and misinformation that Cofer experienced weren’t isolated. When he went to vote, Jim Peterson was also told that he was voting in the wrong county, even though he hadn’t lived at the address on record since 1993. He cast a provisional ballot, which was rejected. Other voters, like Kia Carter, weren’t even offered that opportunity. Though Carter was born in Virginia and has voted in Georgia for the past 18 years, she was flagged as a noncitizen and denied a ballot—in violation of federal law.

In fact, thousands of voters had their provisionals withheld or rejected in Georgia during the 2018 midterms, which is especially troubling considering that these ballots are meant to be used as a failsafe, the last line of defense before disenfranchisement. Instead, they were, at best, used to cover up systemic problems, of which there were many: unsecured election databases, incorrect voting rolls, unreliable voting machines, undelivered absentee ballots, and suspiciously high rates of ballot fatigue. At worst, they required voters to essentially vote twice to have their ballot counted.

Since the midterms, the state has committed $107 million to buying voting equipment that leaves a paper trail, unlike the current 17-year-old machines, which, according to a recent decision by a federal judge, must be decommissioned by 2020. That ruling also mandated that four cities in Cobb County test hand-marked paper ballots in case of problems with the new machines, which are already being challenged as unconstitutional. The secretary of state from 2018, Brian Kemp, is also now the governor, after having overseen his own election, making it clear that the defects in Georgia’s election system are far from resolved. In 2020, the stakes will be even higher.

That's because next year, Georgians will not only vote for president, but also two open Senate seats. Though many Democrats had hoped that Stacey Abrams would run for one of them, she decided instead to fully commit to her work with Fair Fight, now a 20-state, multimillion dollar campaign to promote free and fair elections. The issues that typically get the most coverage in this arena are the easily visible ones, like marathon wait times and poll site closures. But with its disastrously complicated and laborious provisional ballots, Georgia has innovated a more effective and less newsworthy way to discourage voters, especially those who are young, underprivileged, or of color: require them to vote twice, or disenfranchise themselves.

I met Michelle Cofer a week after the midterms at a public meeting of the Gwinnett County Board of Elections. Fifty or so people occupied all the room’s chairs, and another three dozen stood along every wall except the one lined with local news cameras. That night, the canvassing board had planned to determine which provisional ballots would be counted, in accordance with federal law.

Two years after the disastrous 2000 presidential election, Congress passed the Help America Vote Act, which, among other things, mandated that all states provide provisional ballots to any voter who believes herself to be eligible but doesn’t appear on the voter rolls. Then, after the polls close that night, the local board of elections determines that voter’s eligibility.

In Georgia, there were two main types of provisional ballots. The first, coded “OP,” is when a voter is in the correct county but at the wrong precinct. Once a voter casts an OP provisional, there’s nothing left for her to do. As long as she’s in the county’s voter database, the board of elections counts her vote for all the races in which she was eligible.

But for voters in the second category, “PR,” the process isn’t so easy. These voters cast a provisional because their names didn’t appear on the rolls, and afterward, they have to take an extra step to verify their eligibility and “cure” their ballot. Often, that means collecting documents that prove their residency and driving to the one board of elections in the county.

That night in Gwinnett, the board was ready to start that process of verification, but earlier in the day, a federal judge had ordered all counties to delay the certification deadline in order to deal with another election problem: absentee ballots with incorrect or missing birthdates. So, for the first hour, the board met behind closed doors to discuss.

When the board returned, they opened the floor for public comments. The first woman to speak implored the board to accept out-of-county provisional ballots, a request the Abrams campaign also made in a lawsuit filed a few days earlier. Essentially, it relies on the same logic as the OP provisional: If we know a voter’s eligible to vote, why not count her ballot for all the statewide races?

The more fundamental issue, however, was that all of these provisionals were only as good as the voter rolls they rely on. At best, that was a shaky foundation. In 2018, according to an investigation by the Atlanta-Journal Constitution, the state’s digital voter rolls (which, according to Cofer, erroneously listed her as a resident of Rockdale) had security flaws that “would have enabled a hacker to delete any voter’s registration ... make changes that might render a voter ineligible ... [or] systematically [target] large numbers of voters who belonged to certain minority groups or those who appeared to favor one political party over another.” (HB 392, a law recently passed by the Republican-dominated legislatures, aims to improve election security).

There was also the state’s “exact match” identity verification process, which was used between 2013 and 2016 to deny 34,874 registration applications who were disproportionately voters of color. In 2017, Kemp’s office settled a federal lawsuit by agreeing to discontinue using the system. A few months later, the Georgia General Assembly passed a law reinstating “exact match,” which flagged roughly 53,000 voters.

Because these citizens could still cast a ballot if they showed proper ID, a requirement for all voters under Georgia law, proponents of the system said it wasn’t suppressive. But the ID had to “substantially match” the registration on file—per the judgement of the poll worker—which created confusion for groups like the 3,000 recently-naturalized citizens who were erroneously omitted from the poll books and refused a ballot. After a group of them sued, a federal judge ruled that they be allowed to vote if they brought their proof of citizenship to the polls. Even then, though, voters are the mercy of poll workers who are not trained in how to recognize and verify naturalization documents. More to the point, though, provisional ballots were never intended to produce this kind of high drama.

In 2004, the first presidential election after HAVA’s passage, roughly 1.9 million provisional ballots were cast nationwide; by 2016, that number had reached 2.4 million. On average, 69 percent of provisional ballots cast in presidential elections and 79 percent of those cast in midterm elections are counted, suggesting that for the most part, when citizens cast a provisional ballot, it’s likely to be counted.

That’s the case in Georgia as well—but only for certain provisionals. According to data requested from the Secretary of State’s office, a little more than four in five of the out-of-precinct “OP” ballots cast in the 2018 midterms were at least partially counted, which is exactly what HAVA intended: a voter leaves work late, doesn’t know if she’ll make it to her assigned polling site in time, and stops at the closest elementary school. Even though her ballot doesn’t have her precinct-specific races, she can still vote for everything else and be relatively sure that it mattered.

But for the nearly 9,500 voters who were offered a “PR” provisional because their names didn’t appear on the rolls, Georgia’s system was far less generous. Seventy-four percent of these ballots were disqualified. There are many potential reasons why that number is so high, like large groups of student, first-time, and low-knowledge voters, demographics that were the cornerstone of Abrams’ campaign strategy. In the larger context of Georgia’s defective voting system, however, it becomes clear that the problems were much bigger than voter error.

On February 19th, the Committee on House Administration Elections Subcommittee held a hearing to address the state’s history of suppression and intimidation, especially with regards to maintaining the voter rolls. In her remarks there, Abrams cited her work with the non-profit she founded, the New Georgia Project, which submitted over 85,000 voter registration applications to the state in the run-up to the 2014 election. According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, only 46,000 of those were approved in time for the registrants to vote (with another 18,000 approved months afterward). The Secretary of State’s office then investigated the New Georgia Project for voter registration fraud, but three years later, the lead investigator found no evidence of wrongdoing.

In her comments, Abrams also asserted that even though Georgia has online registration, “there’s no adequate way to monitor and maintain that voters who apply are actually processed.” Another speaker at the hearing, Stacey Hopkins, brought the postcard she received before the midterms, notifying her that she was in danger of being struck from the rolls under Georgia’s “use it or lose it” policy, which disqualified 107,000 so-called “inactive voters” the previous year. Hopkins told the committee, “I could not have been deemed an inactive voter if myself and my children had just voted that same year.”

In Gwinnett, 788 voters had their registration status questioned and submitted a provisional ballot. Of those, only 36 percent were accepted—and that’s with an unusually motivated electorate. “I’ve been persistent,” said Cofer, “but what about people who voted provisionally, and they thought it counted and they just never followed up?”

Around 10:30 on the night of the midterms, Jake Best, the communications director for the Democratic candidate for Georgia’s 7th congressional district, Carolyn Bourdeaux, got a Twitter notification on his phone. NBC had called the race for Bourdeaux, a stunning upset for a seat that had been considered “likely Republican” just a few months before. Other outlets quickly echoed NBC, and soon, volunteers were celebrating while top Democrats called Bourdeaux to congratulate her. “Of course we wanted to say we won,” Best said, “but we knew that we hadn’t.”

Georgia’s 7th is split between two counties—Forsyth and Gwinnett—and the early voting totals hadn’t yet come in for Forsyth, where the Democrat candidate in 2016 won only 22 percent. After those numbers dropped, Bourdeaux trailed by a few thousand votes, and the media started doubling back on their projections. According to Best, “There was so much disinformation out there.”

By the time the Bourdeaux staffers went home that night, around 3 a.m., they’d been awake for roughly 24 hours. Still, “I couldn’t sleep,” said Best. “No one could sleep. We were just crunching numbers.” This time, the waiting game was for Gwinnett, which hadn’t yet reported its absentees.

“All day Wednesday, we just sat here, and they would drop 200 at a time, 2,000 at a time, and it was just excruciating,” said Best. When the results stopped updating, it was Wednesday night, and Bourdeaux was down by just 890 votes. To win, the campaign knew they’d need as many voters as possible to cure their provisional and absentee votes before the deadline, which would require them to recalibrate their entire strategy. “It’s hard enough on a campaign to reach people to vote,” said Best, “and now we’re in a situation where we have 36 hours to contact them, confirm that they’re the right person, and get them to take an action.”

After doing their best to train volunteers, staffers shifted their focus to combing over the handwritten lists of provisional voters from each of the 124 precincts. Gwinnett is one of the most diverse counties in the southeast, so the names weren’t always familiar to the election staff. As one Bourdeaux staffer told me, “It’s a total shit show. If somebody shows up without an ID, then it’s just the poll worker writing down the name they’re hearing. If you’re Vietnamese, there are like six different naming constructs.”

Before the campaign could contact the voter, though, they had to decide exactly what their message would be. Said Best, “It’s hard to call a voter and say, ‘Hey, so we’ve been calling you for weeks, and the election was two days ago, but it’s still not over. Right now, we need you to go to Lawrenceville with your ID.” Because every provisional ballot requires a different cure, the campaign had to write separate scripts for each and then run them by lawyers from the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, who had flown in for that purpose.

Once those scripts were ready, the mad dash began. Volunteers and staffers tried to reach voters by calling, texting, using Facebook, and driving to their homes, some of which were in areas that were under flash flood warnings. Most were exhausted from the months-long campaign, as were the voters, who were also being contacted by the Abrams campaign and organizations like Asian Americans Advancing Justice and the Georgia Association of Latino Elected Officials. “I wish people would stop calling me,” my Lyft driver said when I asked him if he’d heard about the election controversies. He told me he was a voter who never misses an election, but he’d been called at least 10 times in the past week to cure his provisional ballot (he voted in person). “I’m tired of it,” he said. “Let’s just get it done.”

Communicating to voters that their ballot matters is an uphill battle under the best of circumstances, but convincing them to gather the required documentation and travel to their Board of Elections—essentially, to vote again in a race that had, for many, already been decided—is nearly impossible. In the end, Bourdeaux would lose the race by 419 votes, the closest congressional race in the country.

Like the others working to cure ballots, Best was emphatic that the campaign wanted every vote counted—not just those for Bourdeaux. I didn’t believe that (one campaign volunteer told me that they tried to guess voters’ political leanings from their Facebook profiles, which they would’ve been foolish not to), but in Georgia, “provisional ballot” and “Democratic vote” are essentially synonymous.

Republicans were equally able to benefit from helping their provisional voters cure their ballots, but, according to Linda Williams, a volunteer with the Gwinnett County Republican Party, the issue hardly came up during their post-midterm meeting. When I asked her why, she hesitated and then said, “I don’t think many Republicans voted provisional or absentee.”

Williams is somewhat right (with 8,642, Abrams received approximately 2.5 times more provisional votes than Kemp), and at the board of elections meeting in Gwinnett, I asked those who commented against accepting disputed ballots if they had voted provisionally or absentee. They all said no. The closest anyone came was a man whose son is in the Marine Corps and voted absentee. Political beliefs are certainly shaped by personal experiences, and if you’ve never had a problem voting, it’s difficult to believe that others have, but what stood out most to me was these voters’ tone when they answered, as if the question itself were offensive.

The reason provisional ballots have a stigma is that they assume the voter has done something wrong—she hasn’t, say, registered on time or brought the correct ID or showed up to the right poll site. But, what about when the roles are reversed? When it’s the government that’s failed the voters, what recourse do those voters have?

Problems plagued every aspect and every stage of Georgia’s elections. Last September, a federal judge decried the “serious security flaws and vulnerabilities” of the state’s voting machines. This is the judge who would eventually rule that Georgia has to decommission these machines by 2020, but at that time, she refused to force the state to switch to paper ballots, a laborious transition, which, she wrote in her opinion, could “result in voter frustration and disaffection from the voting process.”

Voter frustration and disaffection were not avoided. According to the Fair Fight Action brief, during early voting, some voters’ absentee ballots in Chatham County were returned as undeliverable, despite being mailed with a pre-printed delivery address in an envelope supplied by the county. In Dougherty County, absentee ballots from the county were mailed out late, with at least one postmarked after Election Day. Elsewhere, voters were told they couldn’t cancel their absentee ballot and vote early in person, a right they have under the law, while others saw that their ballots were “approved” on the secretary of state’s website, only to learn later that they had been rejected.

The reason for those rejections was often trivial mistakes, such as the voter not writing her year of birth (like 265 absentee voters in Gwinnett) or because she entered “2018” in that field (46 Gwinnett voters). Especially considering that this information is already printed on the envelope voters use to mail back their ballots, is that reasonable grounds to lose your vote?

According to the Voting Rights Act, it’s not. The law includes a provision that, according to another brief filed against the state of Georgia, “was intended to address the practice of requiring unnecessary information for voter registration with the intent that such requirements would increase the number of errors or omissions on the application forms, thus providing an excuse to disqualify potential voters.”

Nine days after the election, a federal judge agreed, forcing each county to accept ballots despite incorrect or missing birthdates. For other errors, however, like an incorrect address, the rejected voter, if she was made aware of the problem at all, had to cure the ballot herself. (Though a new law, HB 316, now stipulates that neither a voter’s address nor her birthday are required information for absentee ballots, a valid signature is — per the discretion of the counties, which have employed widely divergent standards for these qualifications.)

On Election Day itself, the process was just as chaotic. Despite warnings from the Democratic Party that confusion around the “exact match” system would likely lead to greater demand for provisional ballots (in addition to the state’s record-high turnout during early voting), some precincts ran out of provisionals well before the polls closed, according to the brief filed by Fair Fight Action.

In Fulton County and Gwinnett County, the hours for poll sites were extended because of broken machines, missing power cords, and wait times up to four hours (which, by Georgia’s standards, is fairly normal). Some chose to stay, but as Abrams pointed out in her comments to the Committee on House Administration Subcommittee on Elections, “An untold number simply gave up, unable to bear the financial cost of waiting in line because Georgia does not guarantee paid time off to vote.”

In Fulton, the situation was doubly frustrating because 694 machines were being kept in storage due to a court injunction from over a year earlier. The state doesn’t keep spare machines, whose type is no longer manufactured, nor is a county legally allowed to substitute with paper ballots. “There really wasn’t anything we could do,” said Rick Barron, Fulton’s elections director.

“The unused voting machines in storage is terrible,” said Dave O’Brien at FairVote, a nonpartisan election integrity group, “but what can you do besides put those voting machines in and have another election?”

O’Brien was asking rhetorically, but in Georgia, nothing is off the table. Last September, a judge ordered a Georgia legislature district to redo its Republican primary after the voter rolls were “cross-contaminated” with residents from other districts. In February, the district was ordered to do it yet again. “Getting a new election once is almost unheard of,” said the attorney for one of the candidates. “Getting a new election twice might have never been done.”

A week after the midterms, at a press conference organized by the ACLU of Georgia, a coalition of Georgia politicians and faith leaders, citing the “cloud of credibility” hanging over the election, demanded a runoff between the two candidates for governor. Absent a court order (or the legal threshold that would have triggered a runoff), the request was easily ignored.

Stacey Abrams refuses to meet the same fate. In its lawsuit, Fair Fight Action indicts all of Georgia’s electoral system, from its voter rolls to its direct-recording electronic machines to its closed polling sites and habitually long lines. Perhaps the most ambitious remedy the lawsuit proposes is placing Georgia’s election administration back under the purview of the federal government.

Called “preclearance,” this provision of the Voting Rights Act was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013. Since then, Georgia has closed 218 polling sites in neighborhoods that are disproportionately poor and minority. Last August, a consultant recommended that Randolph County, a predominantly black area, close seven of its nine polling locations, and the ACLU of Georgia threatened to file suit under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

According to another person testifying at the House hearing on February 19th, Gilda Daniels, a former deputy chief in the Voting Section of the Department of Justice, these cases last an average of three years and cost more than $1 million. In this instance, however, no legal action was needed. Public outcry forced the county to backtrack, though three (overwhelmingly white) poll sites are now slated to close.

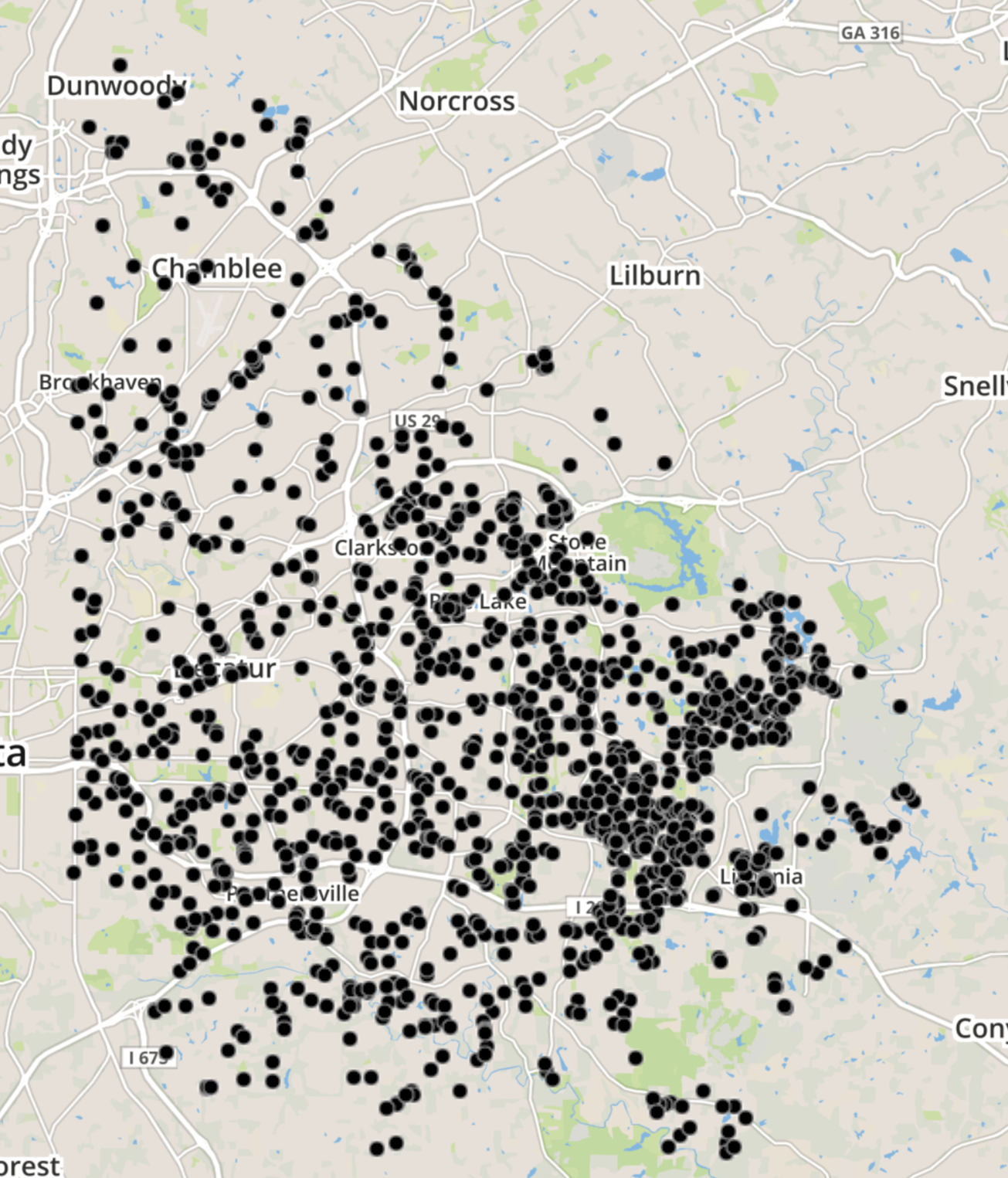

Based on the distribution of provisional ballots, this burden wasn’t incurred equally. The map above, created by Fair Fight Action, is of DeKalb, which voted for Abrams by a 61-point margin. Each black dot represents one provisional ballot cast, and though the data isn’t perfect (FFA matched the name reported on the provisional ballot with a registered voter in the county), they reveal a clear pattern: Voters in the northern part of the county filled out far fewer provisionals than those in the eastern and southern areas, which have lower median incomes and relatively more African Americans.

The high number of provisionals isn’t necessarily a problem, though. When I asked Deb Cox, the elections supervisor for Lowndes, why her county had more provisional ballots relative to other, similarly-sized counties, she wrote in an email, “The real question isn’t why do we have so many, but why do other counties not have more?”

For Cox, provisionals grant her and her staff the extra time needed to verify a voter’s eligibility. “There are so many ways to register,” she wrote, “and so many places to register, and so many groups doing voter registration both through the mail and in-person, and sometimes groups are not as meticulous as they need to be about transmitting those voter registration forms to the elections offices, that we err on the side of the voter always.”

The real questions, according to Cox, are these: “Is anyone being turned away and not allowed to vote provisional? Are poll workers suggesting (or overtly stating) that provisionals don’t count and dissuading people from voting provisional?”

Whose fault was it that Michelle Cofer’s vote wasn’t counted? Hers, for not verifying her new registration before she voted? “I just assumed that everything was fine,” she said. “My husband’s updated, but I guess mine never did. You get bombarded with mail during election time, and I never really paid attention if it was my name or his name.”

Was it the fault of the person who gave her the re-registration form but potentially never submitted it? The election administrator who possibly failed to enter it into the system? The poll worker who not only told her not to drive to Rockdale but also failed to give her the necessary information to check if her ballot had been counted, a requirement under federal law?

Under the best of circumstances, elections are messy, but especially in Georgia, chaos reigns, and that’s not necessarily a coincidence. Lawsuits create confusion and uncertainty, and in the lead-up to election day, at least five were filed against the state in federal court, changing the standards for accepting or denying ballots so quickly that not even the election officials could keep up. Some responded by erring on the side of the voters. Some didn’t.

At the same time, policies like the state’s “exact match” policy aren’t necessarily suppressive in and of themselves. They do, however, generate enough headlines about registration “purges” to discourage some citizens from even attempting to vote. In this regard, no single facet of Georgia’s election system is unimpeachable evidence of orchestrated voter suppression—not the provisional ballots, closed polling sites, long lines, rejected absentees, impounded voting machines, digital vulnerabilities, or database glitches.

When combined, though, these problems reflect a slurry of confusion, incompetence, and neglect that has the same effect as wrongdoing and, more importantly, is plausibly deniable, especially when the responsibility for running elections is split between the state and the counties. “They each point the finger at one another,” said Sara Henderson, the Executive Director of Common Cause Georgia, a non-profit, non-partisan advocacy organization that also sued the state during the midterms. “But, neither one will be held culpable or accountable for running the elections process.”

Consider one of the many rulings issued after Election Day in 2018, in which Judge Totenberg ordered that a hotline be established for voters to determine whether their ballot had been counted or not. Why would a judge need to tell the state to do something that’s already required under federal and state law? “I don't know,” said Chris Harvey, the Elections Director for Georgia. “I can't explain the judge's order.”

When asked whether the high rate of rejected provisional ballots suggested that there was a problem with the voting system, Harvey said no. “If there were people that were properly registered whose provisional ballots were not counted, I'm confident we would have seen some type of outcry,” he said. “I'm not aware of any kind of outcry like that.” After being reminded that he issued a declaration in the Common Cause lawsuit, which made exactly those allegations, he said he still didn’t recall specifics. In an email a week later, he clarified that he meant that a large number of PR provisionals weren’t later found to be eligible.

In defense of Georgia’s voting system, Harvey cited its three weeks of advanced voting, its 45-day advanced voting by mail, and its automatic voter registration system, implemented in 2016, which increased voter registration by an estimated 94%. However, according to data from the Census, the registration rate is still below the national average, possibly because Georgians are automatically enrolled only if they visit a state agency. Otherwise, the state has one of the most restrictive registration deadlines in the country.

Last week, about 300,000 voters were notified (and not without controversy) that they’re considered “inactive” and could have their registrations cancelled. Although the Supreme Court has ruled that this “use it or lose it” policy is constitutional, Tammy Patrick, a former commissioner on the Presidential Commission on Election Administration, said that there are more proactive ways to maintain accurate rolls, like mailing out voter guides, sample ballots, or poll place notification cards. “Those states that interact frequently with their voters tend to have more current information,” she said.

According to Henderson, the state could make other significant reforms, like increasing compensation for poll workers, who work roughly 14 hours on election day and, in some counties, are paid just $5.15 an hour. Even something as seemingly minor as printing separate envelopes for each type of provisional ballot would be progress. “It seems silly,” said Henderson, “but it would save a ton of ballots and a ton of time, too, because people wouldn’t have to decipher someone else’s handwriting.”

An even more efficient reform would be to pass same-day voter registration, which is available in 20 states and is similar to issuing a provisional ballot. A voter who goes to the polls and isn’t on the rolls applies for a conditional registration (using the ID she’s required to show in Georgia), and the onus of determining her eligibility is then on the board of elections, not on her. Said Henderson, “They wouldn’t have to worry about proving that their ballots should be counted.”

As hard as she tried, Michelle Cofer couldn’t prove that her ballot should be counted, but, surprisingly, she isn’t discouraged by her ordeal. She used to be politically active—“I was out there, on the streets, voter registration, board of education, city council, everything” she said—but eventually became disillusioned. “I used to be that person who thought, ‘This stuff is rigged. It don’t matter.’”

Now, Cofer is politically mobilized again. She said that her experience with the provisional ballot, which was so frustrating for so many voters, had the opposite effect on her. “I feel like this awoke something in me,” she said, “like it reignited a vigor to make sure that equality is really equality.”

Follow Spenser Mestel on Twitter.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

from VICE https://ift.tt/2PPkj50

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment