CHICAGO — Soon after Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke was sentenced to almost seven years in prison for gunning down 17-year-old Laquan McDonald, his colleagues did something fairly common to frustrated police departments: They started working less.

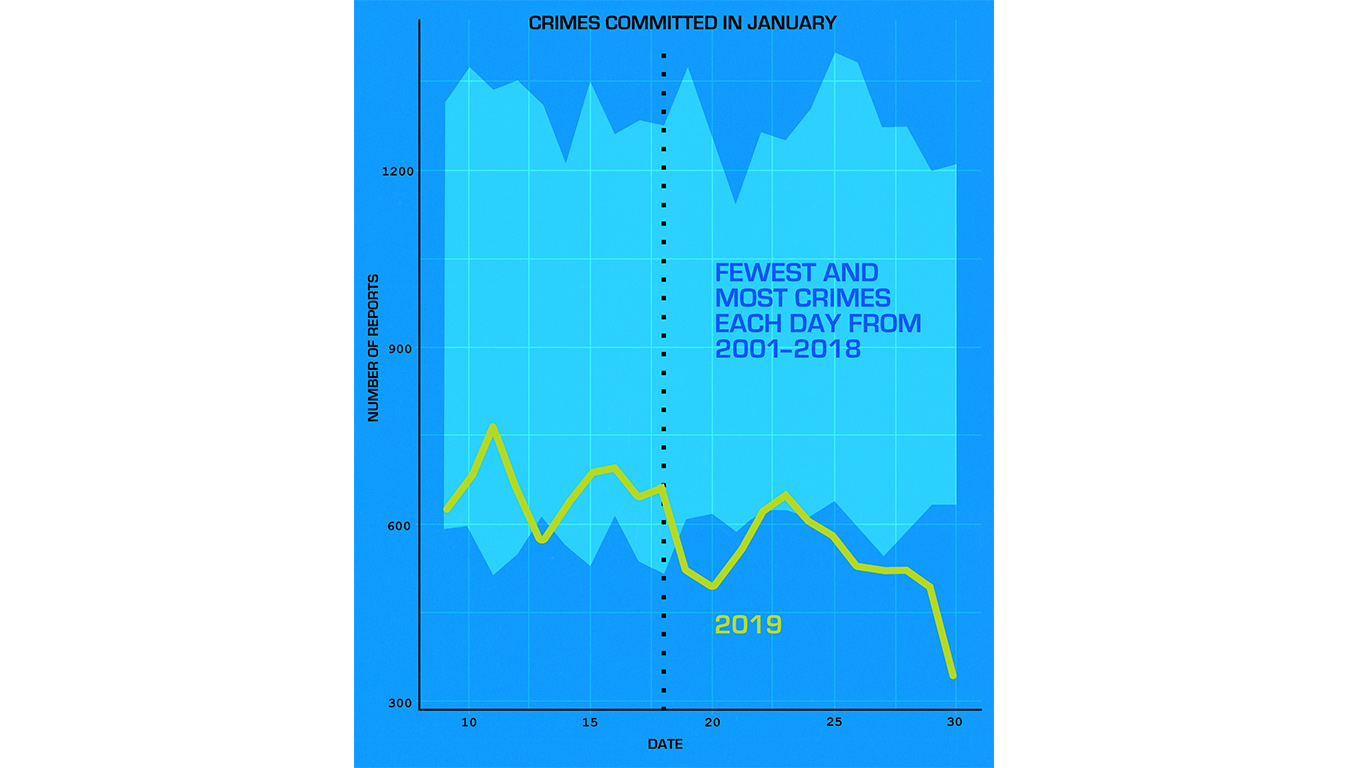

Furious at the verdict, the state police union issued a veiled threat the same day asking whether citizens of Chicago were “ready to pay the price” of police officers not feeling comfortable doing their jobs. And while the Chicago Police Department has denied there was any work slowdown, an analysis of crime data by VICE News shows a significant reduction in police activity following Van Dyke’s sentencing on January 18.

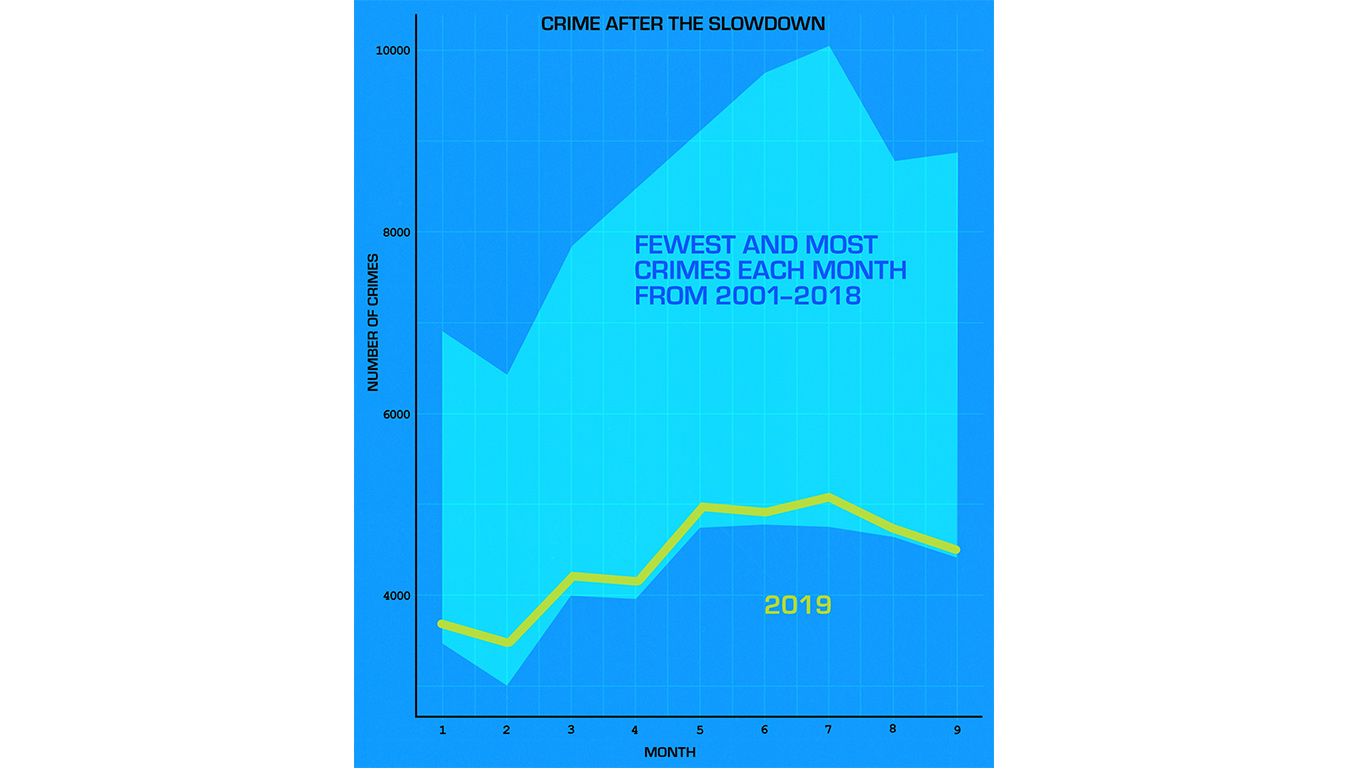

Arrests by Chicago police officers dropped by nearly 50% citywide the evening after the sentence came down, and almost 25% in the two weeks following. At the same time, total crime as reported by police dropped to the lowest level in at least two decades, a stat consistent with a policing slowdown. Crime reports arising through street stops, such as drug arrests and weapons violations, fell the most precipitously, as officers continued to respond to serious incidents like shootings.

Police see slowdowns as a way of punishing a community by letting crime flourish unaddressed. But in Chicago, something unexpected happened: While arrests and crime reports by police fell during the two-week slowdown, they stayed low when police returned to work.

In the weeks and months following Van Dyke’s sentencing, serious crime continued to decline even though cops had returned to more active policing. So far in 2019, the number of homicides — which was previously among the highest in the U.S. — has dropped by 8%. Murders have fallen to their lowest level in five years. Shootings are down 9% compared to last year. Police were doing less, but somehow Chicago became safer.

Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot even used a press conference with the city’s police chief to note the improvement, saying the city was “trending in the right direction but has a long way to go.”

The proof of a slowdown lies in the fact that three particular kinds of arrests virtually stopped: drug possession, weapons violations and prostitution. This is important because narcotics, weapons and prostitution arrests are an indicator of a type of policing known as “proactive,” in which officers initiate encounters with citizens without the report of a crime. This can include stopping people based on “suspicious activity” — which can be interpreted as standing on a particular corner or moving away from a police car. Proactive policing is a fraught and controversial practice, as people of color are often disproportionately targeted.

Between January 18 and January 31, the two weeks after Van Dyke’s sentencing, police made less than one-third the average number of narcotics arrests in the previous 18 years. Prostitution arrests fell by about 90% from the average over the same time period. Weapons violations dropped as well. The massive decline suggests that officers weren’t stopping people on the street nearly as often.

“It’s possible that [citizens said], ‘OK, finally somebody’s doing something; they’re listening.’”

During the slowdown, the crime reduction was also concentrated within black and Latino communities on the city’s south and west sides with higher crime rates, suggesting that different groups of police officers responded to the union calls for a slowdown differently. Former Baltimore police officer and professor of law and police science at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice Peter Moskos said many cops ignore such statements by the union.

It isn’t possible to definitively determine the reason for the crime reduction after the slowdown ended. But some experts believe the drop in proactive policing, or sentencing — or both — may have improved relationships between Chicagoans and the police, ultimately playing a significant role in driving crime down.

There’s some evidence that was the case. Excessive force complaints have fallen by more than 13% so far this year. “That would suggest some improvement in police-community relations,” said Richard Rosenfeld, a professor of criminology at the University of Missouri at St. Louis. Van Dyke’s sentence may have also helped to quell anger at the department. Public reaction to the jail term varied, with McDonald’s family describing it as a “victory” while some police reform activists termed it “a slap in the face.”

“It’s possible that [citizens said], ‘OK, finally somebody’s doing something; they’re listening,’” so there’s less willingness for the public to challenge authority, and that would bleed into [fewer] other conflicts as well,” said Scott Wolfe, a professor of criminology at Michigan State University.

And better relationships between officers and the public might lead to more tips and information that could improve the police’s ability to deter and solve crimes in their districts. The arrest rate for homicides, which had hovered below 20% before the sentencing, experienced a sharp uptick to around 23% in the following months. Since the sentence, it has increased to the highest level it had been in four years.

Chicago Police Department spokesman Anthony Guglielmi credited the decline in crime to “considerable investments in data and technology” as well as community policing. He cited gunshot-detecting microphones scattered throughout the city as helping to deter crime and enabling police to more rapidly respond to shootings. But many aspects of Chicago’s violence-reduction strategy — including the gunshot-detection technology — had been in place since 2017 or earlier, long before the inflection point in arrests and crime this past January.

Chicago’s policing slowdown and subsequent decrease in crime was echoed in New York City only months later, and under similar circumstances.

In mid-August, five years after police officer Daniel Pantaleo choked Eric Garner to death for resisting arrest, the New York police commissioner removed the cop from duty. New York City police answered by beginning a slowdown: In the week following Pantaleo’s firing, arrests dropped by 27% compared to the prior year, a reduction that police privately admitted was retaliation for what they viewed as an unjust dismissal.

The New York police union also made oblique threats about public safety. But serious crime is down more than 1% so far in 2019 vs. 2018.

READ: It’s nearly impossible to sue a cop for shooting someone.

There is precedent for slowdowns failing to negatively affect crime — and sometimes even reducing it. In 2015, when an assailant killed two New York City officers in their patrol car, cops also slowed down their policing. The pullback resulted in major declines in proactive policing, ticketing, and arrests, just like this year after Pantaleo was removed.

Researchers at Louisiana State University and the University of Michigan found that violent crimes fell during and after the slowdown. Their study showed that there were thousands fewer major crime reports and that the reduction continued for more than three months beyond the end of the slowdown.

Various other research has also indicated little impact or small reductions in crime after slowdowns. “They say they’re pulling back, that their colleagues are pulling back, and the data would suggest that indeed they are. But what we’re not seeing a lot of, at least on average is … change in crime,” Wolfe said of his own findings.

His study focused on a policing slowdown after the August 2014 killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. There, traffic stops fell precipitously after massive protests, but the rate at which officers recovered contraband in stops actually increased — which suggests a decrease in proactive policing meant cops were focusing on citizens who were more likely to be actually breaking the law.

READ: Police promised witnesses free Ring surveillance cameras if they testified against neighbors.

Chicago PD spokesman Guglielmi disputed the slowdown in an interview with VICE News, and noted that some measures of morale, like sick days, did not increase after Van Dyke’s sentencing. But he didn’t explain why arrests declined so dramatically. Another significant influencer of crime — the weather — wouldn’t explain such a severe dropoff. The state union did not respond to multiple requests for comment, and the local chapter declined to comment.

And as narcotics stops and other forms of proactive policing have begun to increase in Chicago again, the crime rate has also increased in the latter half of the year. Excessive force complaints were down by more than 20% in the first half of the year, but they’ve begun to return to their old rates as well. Like the 2015 slowdown in New York, any effects of the slowdown — whether positive or negative — may be only temporary.

But Rosenfeld said that the declines in arrests in New York and Chicago are part of a longer-term, more widespread trend toward fewer stops and reduced policing across the nation. Litigation and public outcry against aggressive proactive practices like New York’s stop-and-frisk program — which was shown to be used mostly to stop and search minorities — has drastically cut the number of arrests for minor offenses. According to his research, arrest rates for all kinds of offenses have been decreasing for at least a decade, beginning years before videos of police violence led to a massive protest movement led by Black Lives Matter.

“We have been witnessing, in the United States, in the big cities certainly, something akin to a long-term depolicing effort … with no subsequent effect on crime rates,” Rosenfeld said.

Graphics by Hunter French.

from VICE https://ift.tt/386VMil

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment