At the very start of this year, the fitness startup ClassPass delivered the sort of update that would make any Silicon Valley founder salivate. According to its most recent fundraising round, the company was now valued at more than $1 billion, earning it the enviable honor of becoming the first “unicorn” of the decade.

It was a remarkable milestone for the company, which built a business around offering discounted fitness classes to subscribers around the world. CEO Fritz Lanman suggested the new $285 million investment would help put ClassPass on course to eventually go public. But the “first order” of business, he said, was “to build a healthy, global sustainable business, and we're doing that.”

At some of the company’s thousands of partner studios, things felt decidedly less joyous. The previous October, Leila Burrows, the operating owner of a San Francisco-based yoga and pilates studio called The Pad, sent out an email to her students with distressing news. The Pad, Burrows explained in the email, could no longer afford to continue its “increasingly contentious relationship” with ClassPass. “Classpass continually tries to take more and more control over our business,” she wrote. “With their latest iteration, it is now crystal clear it is no longer financially viable for us to continue the partnership. So, we The Pad, have chosen to pull ourselves from Classpass.”

Two months later, across the country, the owners of New York-based chain Yoga Vida sent out a similar email to its own students, saying that it had “become increasingly evident that we can not sustain our business AND remain on the CP platform.”

“As the costs to operate our business rise, our CP revenue goes down on [a] greater volume [of customers] every year,” the owners wrote. The people at Yoga Vida had determined they, too, had little choice but to get off the platform as soon as possible.

On the way to its billion-dollar valuation, ClassPass had long depended on fitness studios like The Pad and Yoga Vida, which accepted ClassPass students into their classes a few times a month at rates far below what they asked of their direct customers. In exchange, the company offered studios free marketing, a few extra customers, and the hope that the ClassPass students might eventually convert to full-paying direct members.

For a while, the deal worked well enough: Subscribers got great deals on fitness classes, studios got new potential customers, and ClassPass grew tremendously. But with an IPO in the fitness company’s sights, many of the same studio owners who helped ClassPass grow into a vaunted unicorn are now panicking about changes to the ClassPass system that they say threaten their very existence.

“ClassPass is squeezing studios to the point of death,” said one New York studio owner. “It's really serious,” said another. “It's very, very hard for a single-location studio like ourselves to frankly almost keep our doors open.” (VICE withheld the names of some studio owners who feared retribution due to ClassPass’s terms and conditions, which require partners not to disclose “any non-public information” or “make any comparative references to ClassPass.”) According to interviews with 18 current and former ClassPass partners, the company has stripped control of studios from their owners and instituted an algorithm-based model they don’t trust, which drives per-student payments as low as $7—far below what some studio owners see as sustainable.

To make matters worse, studio owners contend, ClassPass's investor-funded model detached the price of classes from their brick-and-mortar costs—and those low prices in turn helped ClassPass obtain market share while devaluing the product.

The situation has created an ecosystem where some studios fear they can’t survive, with or without ClassPass.

“They've created this monster for us, where we are damned if we do and damned if we don't,” said Paula Tursi, who runs Reflections Yoga NYC.

“It's totally killing our business,” Burrows said. “ClassPass needs to go.”

Have you ever worked at ClassPass? Or are you a ClassPass partner? We'd love to hear from you. Send an email to maxwell.strachan@vice.com or maxwellstrachan@protonmail.com or reach out on Signal at (310) 614-3752.

ClassPass disputed many of the studio owners’ claims in this article, saying they represent the feelings of only a small minority of the company’s 30,000-plus partners.

“We are always rooting for our partners to succeed. Doing so is core to our mission, while also being in our economic best interest,” ClassPass spokesperson Mandy Menaker wrote over email. “We are continually refining our offering in order to send more members to more studios and support the growth of the industry at large.”

Like many other studio owners, Burrows was intrigued by the prospect of partnering with ClassPass when the company first approached her in 2015. While the startup only paid her a fixed rate of $12.38 per student, less than the $16 she received from a direct customer, Burrows had total control over how much inventory she wanted to allocate to ClassPass. “You know, what classes and what teachers and how many spots,” she said.

In the early years, ClassPass students could only attend a studio three times a month, which meant the service worked well as a free and limited marketing tool. If a ClassPass user liked the studio, the owner could work to convert them to direct members.

“The pitch was: It's kind of gravy,” said David Acker, the co-founder of Love Story Yoga in San Francisco and Turnstyle Cycle & Bootcamp in Boston. “Some customers will be on this. It’ll get you more exposure, and we’ll pay you 50 percent of your 10-pack price [i.e. half of an already-discounted rate] for anyone that comes.”

On the customer side, the benefit was obvious: Early on, ClassPass charged just $99 for 10 monthly boutique fitness classes, which on their own each could cost $35 a pop. Later, it expanded the model to allow for a month of unlimited classes for that same price. The subscription made it so that ClassPass customers could attend a cheap yoga class on Tuesday, a cheap spin class on Wednesday, and a cheap barre class on Thursday.

The strategy quickly made ClassPass the name in fitness. Exercise enthusiasts joined the platform, and studios followed. “Everybody jumped on. Everybody else had to jump on, and it just became mania,” said Tursi, who appreciated the marketing opportunities ClassPass provided. By 2015, ClassPass had made more than 4 million reservations at more than 4,000 studios. The deals seemed almost too good to be true. “They bought market share with an unsustainable model,” said one New York City studio owner.

ClassPass paid studios at low rates, but was charging customers even less, leaving the startup to find investors to pick up the tab. In 2014 and 2015 alone, the company pulled in $86 million in funding, according to CrunchBase.

“It is the poster child for Silicon Valley,” said Acker. “It gets a customer hooked on something great at an artificially low price.” (“Our customers, if anything, are hooked on variety,” countered Menaker.)

Nevertheless, ClassPass still worried about how much it was spending on classes. Internal company documents obtained by VICE boasted in February 2016 that the company’s projected annual revenue had risen to $122 million. But they also noted the company was making 300,000 reservations a week with “average studio payout rates” of “$12+,” which amounted to about $187 million paid to studios in a single year—meaning the company owed $65 million more than it expected to make that year.

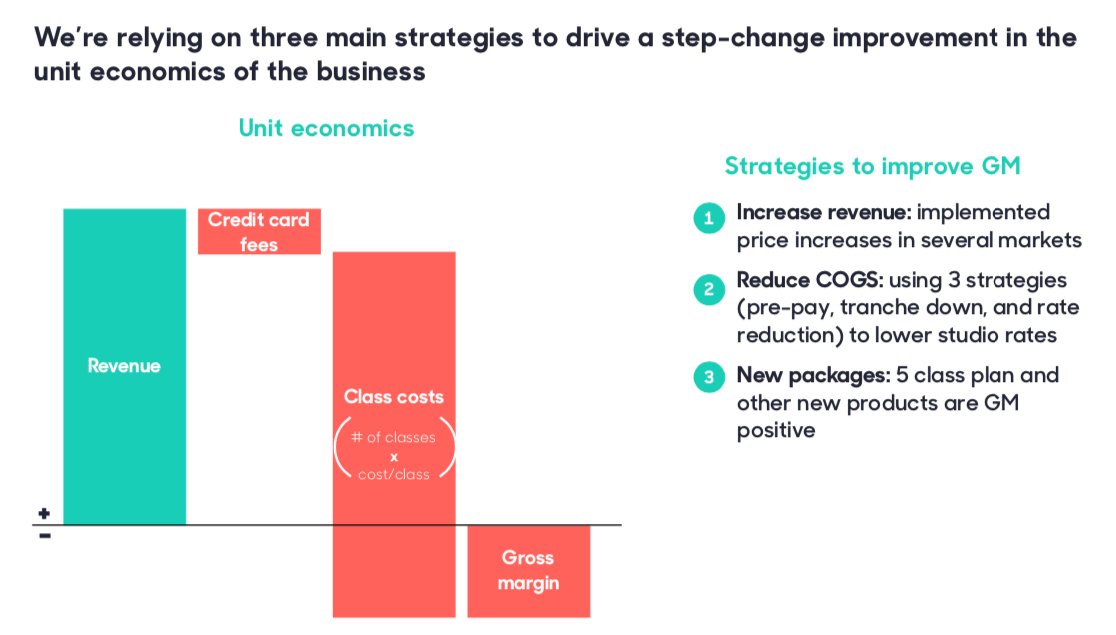

In the documents, ClassPass made clear that part of improving the company’s financial forecast would involve reducing the amount it spent on classes while placating studios’ concerns. The way to do so was to “lower studio rates,” partially by “routing users to cheaper inventory”—meaning pointing customers towards classes in less-desirable time slots—while “shifting conversation” with studios “to overall revenue vs. rate per class.” (ClassPass told VICE any improvements to its business since 2016 have been the result of alterations to its “packaging and pricing” and not because of “changes to studio rates.”)

That same year, the company also tried to raise the prices of the wildly popular unlimited-class plan, before doing away with it entirely, explaining that it had proven to be “unsustainable.” In response, the company faced anger and backlash from users. But the model wasn’t working, and ClassPass needed to find one that did.

By March 2017, founder Payal Kadakia had stepped down as CEO, switching roles with then-executive chairman Lanman, an investor in companies like Square and Pinterest. One year later, ClassPass announced a series of changes that were as convoluted as they were dramatic. The company had formally switched over to a credits-based system, where students paid the same amount every month in exchange for a set amount of credits they could spend however they wished.

While the earliest iterations of the site valued all classes equally, the credits model allowed for variation. A techno-pumping Thursday night spin class might cost customers 12 credits while a quiet Monday afternoon yoga class might cost five. The switch solved a problem: It made cheaper classes more appealing to customers, which was a boon for ClassPass.

As part of the changes, ClassPass also announced two other alterations: It would no longer limit the number of times one ClassPass customer could attend his or her favorite studio and allowed people to pay more credits to go to “premium” classes “during high demand and peak class times.”

The company had previously paid studios at one pre-negotiated fixed rate, but now it also paid studios for premium classes at a separate higher rate—often near the drop-in rate, said studio owners, who could decide how many spots they were willing to open up to premium pricing.

“This was perfect for us as a studio because we're getting what we should be getting,” said one New York studio owner. “We were able to say, ‘Okay, we don't want anyone to come to these time slots, unless they're gonna pay, you know, $18 for the class,’” agreed a Los Angeles studio owner. “And that was fine.”

It was a steep price to pay for ClassPass, but the benefit was inarguable: With more spots available, customers now had less reason to leave the platform. Studios also began to rely on ClassPass for a significant and growing percentage of their revenue. Burrows said ClassPass came to represent an average of 20 percent of The Pad’s visitors every month. Most studio owners I spoke with put the number far higher—some as high as 90 percent. “We're dependent on the couple of thousand dollars we get from them every month,” said Tursi of Reflections Yoga NYC.

In October 2018, I joined the ClassPass platform myself. Like many other ClassPass users, I was lured in by a promotion that allowed me to take two weeks of unlimited free classes (some promotions run for a month). By the end of it, I was a paying customer, forking over the lowest possible amount—$15 a month—in exchange for nine credits, which I deduced could get me roughly two monthly yoga classes if I was willing to hunt for basement deals.

The month I joined, Lanman described the new system as a model where ClassPass, studios, and customers all won. “We make more money the more [customers] spend and use their points,” he said. To make money, ClassPass previously had to “hope that customers would not work out”—which is the typical breakage model of an old-school gym—“or we had to negotiate a lower rate with the studios,” Lanman said. By comparison, the new system aligned everyone’s interests. ClassPass simply took a “very small” percentage each time a customer booked a class on the platform—typically around 5 percent as of 2019, according to an internal document.

Because of that commission, ClassPass no longer had a reason to set studios’ rates low unless doing so maximized a studio’s revenue, the company told VICE. “There is no race to the bottom on payout rates across the ClassPass network,” Menaker said.

But many studio owners said tussles with the fitness giant over rates became a central aspect of the relationship—one that a New York City studio owner compared to “Uber versus a single [New York City taxi] medallion owner.” ClassPass’s thousands of partners each negotiated their own individual contracts with the company. And the administrators of Jivamukti Yoga Center in New York told VICE that ClassPass “firmly pressure[d] studios to drop the value of the product.” Tursi charges $25 for a drop-in and offers three classes for $38 to new students. ClassPass, meanwhile, was paying $8 per class until recently. “That money goes straight to your teacher,” Tursi said. “She gets paid and we get nothing—maybe we make two or three dollars.”

Tursi was eventually able to argue for a rate increase, but many others weren’t so lucky. A Los Angeles studio owner said he tried to negotiate a new rate to sustain his business, which ClassPass had once seemed amenable to. “And they said, ‘No, we're not doing that. We can’t do that,’” the studio owner said. The same thing happened to Acker of Love Story Yoga, whose costs necessitated he raise rates at his studios.

“When I reached out to them and said that our 10-pack price has increased and we need our Classpass payout to increase as well, they said, ‘Oh, we don't do that anymore,’” Acker said.

“Rent goes up every year. Minimum wage in San Francisco goes up every year,” Acker added. “And the payout on ClassPass only keeps going down. That is not sustainable.”

When ClassPass announced its billion-dollar valuation last month, Lanman boasted that ClassPass is “consistently” the “#1 driver of new customer reservations” for studios; ClassPass told VICE that the “number one reason” people leave ClassPass is to directly purchase from a studio. But not many people actually wanted to leave the platform, and for good reason. With such a large discrepancy between what ClassPass and the studios themselves charged for classes, the idea that ClassPass users would ever magically transition to full-paying direct customers started to feel like a farce. “A ClassPass customer almost never converts to being a member of the Yoga Studio,” the Jivamukti administrators said. Studio owners themselves understood why.

“What rationally minded consumer would ever buy through a studio?” asked one of the New York studio owners. “They're given every incentive to go through ClassPass because you're buying things at a 50-to-65 percent discount.”

The studio owners were right: They stood little chance of winning over ClassPass users, and ClassPass knew it. Under the new model, the company’s pitch to studios shifted. It was no longer to find potential customers. “Rather, our proposition is that we let partners opaquely clear excess capacity [i.e. fill up their empty class slots without letting the customer see the price] at prices that maximize partners’ overall revenue, with no effort, no marketing spend and no customer service costs,” Menaker said.

Something else happened too: With fewer limits on ClassPass customers, studio owners found that their dedicated students who hadn’t previously used ClassPass were now coming through the platform to save money. “People that used to book solely with us have switched over because it's literally cheaper,” Tursi said, adding that she tried to compete by creating a lower package.

Others felt there was no way to do so.

“We can't convert those people back away from ClassPass because we can’t compete with what they can offer,” said Tamatha Hauskens, co-owner of Remedy Barre + Foam Rolling in Oakland, California. “We have to deal in the real world with paying real rent, training real instructors—all of those kinds of operational expenses that they're free from.”

ClassPass denies this characterization, telling VICE that since a large number of class spots in the U.S. fitness industry go unfilled every day, it had no need to cannibalize studios’ customer base. ClassPass survey data shows that 80 percent of ClassPass users had not previously visited the studios they attend through the platform and half had not visited fitness studios at all in the year before they joined ClassPass. “[O]ur system is designed not to compete with partners’ direct businesses,” Menaker said.

But after wiggling its way inside thousands of studios, the system had nonetheless begun to seem like exactly that: not so much a partner as a competitor—one that had control over the rules of the game. On its website, ClassPass proudly boasts that customers can “save up to 70% off drop-in rates.” “Sweat your workouts – not their prices,” the company says. Meanwhile, ClassPass partners can’t make the same comparisons. The company makes partners agree that the terms of their deals “will never be visible to ClassPass users,” according to one partner agreement, and requests that partners never target ClassPass customers with promotions, “undercut ClassPass pricing” or “make any comparative references to ClassPass,” according to its terms and conditions.

The model works well for some of ClassPass' thousands of partners. Employees at BollyX, a Bollywood-inspired dance-fitness program, told VICE that they were happy with the ClassPass platform even though discounted ClassPassers accounted for upwards of 90 percent of students at their New York studio. “Would you rather have half the studio full and paying full price? Or would you rather give up some revenue to have a full studio?” co-founder Shahil Patel asked. For BollyX, the answer was the latter.

Tim Suski, the co-owner of the national indoor cycling Rush Cycle franchise, said his company greatly benefited from its ClassPass partnership. The same goes for Cassie Piasecki, the CEO of the California-based boutique cycling company GritCycle. Suski and Piasecki—each put in contact with VICE by ClassPass—said ClassPass’s ability to send in new potential customers and fill up classes helped them grow tremendously. Rush Cycle now has 25 franchises and counting, and GritCycle recently opened up its seventh studio; both suggested that the impact on smaller studios might be different.

But as its size and influence grew, ClassPass loomed over the entire industry. Whether they were ClassPass partners or not, studio owners felt the company was putting downward pressure on their already-tight margins. ClassPass claims it’s had no effect on the broader fitness market’s prices. “ClassPass’s share of the overall US studio fitness industry is a low single digit percentage,” said Menaker. But the Jivamukti administrators said selling a $25 class for $8.50 has caused “the products and services to get permanently devalued in the public perception.” “It devalued what we do,” agreed one of the Los Angeles studio owners. “It feels [to customers] like this should be cheap or free and then they don't expect to pay much for classes.”

“It's absolutely undermining the entire world of fitness and of yoga,” said Alison West, the director of New York City’s Yoga Union, which is not on ClassPass.

In an interview with VICE, Lanman conceded that ClassPass may have reduced friction in the industry, making it simpler for users to jump from studio to studio in crowded markets like New York City instead of ever buying directly from any one of them. That’s what I did myself as a ClassPass user. “It's possible that ClassPass has made it easier to see what the competition is,” he said. But he insisted the ClassPass model was preferable to others, since booking on ClassPass came with tradeoffs for customers, like not being able to book a specific bike in spin class.

“If ClassPass didn't exist, you still would have some other aggregator that probably would have an Expedia-like open marketplace model,” he said.

Lanman doesn’t believe it’s realistic to expect studios to ever prefer a customer visit through ClassPass. But he’s confident that his model is “as friendly as you can imagine.”

“We're revenue-aligned. We provide opacity [so that customers don’t know exactly what they’re paying per class]. There’s genuine customer trade-offs from coming through ClassPass.

"And I think that's as good as it gets."

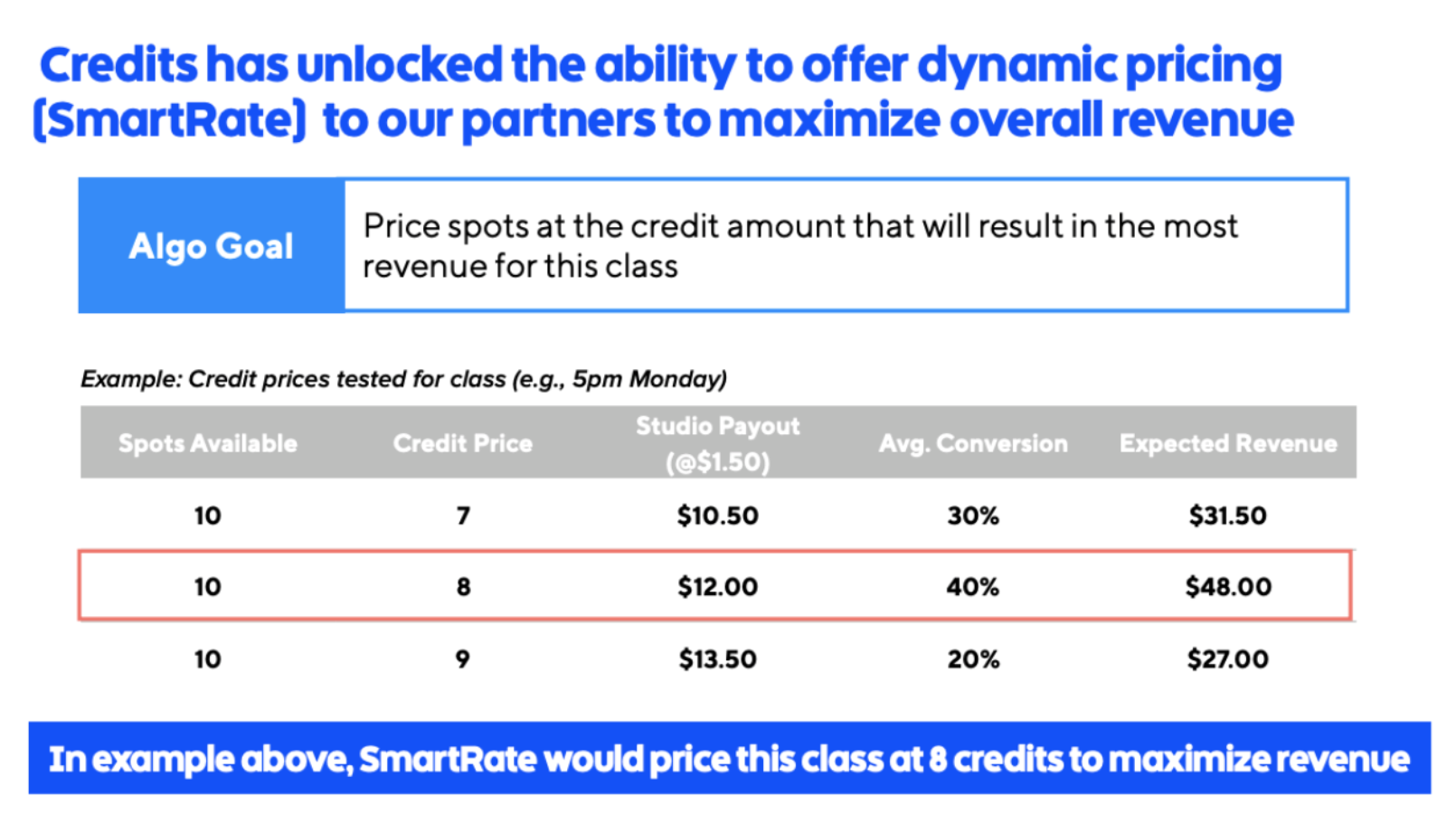

By 2018, ClassPass was pushing studios to adopt something new: its “dynamic pricing technology,” which came to be known as SmartRate.

The algorithm-based technology fundamentally reshaped the partner experience. Each studio now agreed to a price floor and price ceiling, and the algorithm deduced exactly what price would draw in the most total revenue at any one moment. ClassPass compared it to the pricing options in the hotel and airline industry and told partners that the technology would increase their revenue, according to company emails.

With SmartRate, there was no limit to the number of times someone could attend a studio or reasons why it cost what it did. “There's an infinite amount of variables that could inform what the revenue-maximizing rate is,” Lanman said. “Surely, it's self-evident that machine learning is better than human arbitrary set prices at figuring out how to maximize revenue, right?

In tandem with SmartRate, ClassPass pushed partners to try SmartSpot, which the company described as “an automated spot management technology” that “looks at your reservation history to understand how you typically fill your classes and makes real-time adjustments to add or remove the number of spots you release on ClassPass.” SmartSpot required studios to give ClassPass students access to all their classes’ spots, and owners could only hope ClassPass would adhere to its promise not to “list your spots on ClassPass if you normally fill them with your own direct clients, plain and simple.”

ClassPass said neither algorithm considers the company’s own bottom line when pricing classes. They only help to create a more dynamic marketplace that maximizes revenue by better aligning supply and demand at any one moment.

“Our goal is to get an order of magnitude or two more people into the [fitness] category,” Lanman said, adding that they didn’t dramatically increase the percentage in fees and commissions they took from studios. “We don't think the industry can support much more margin increase. We're happy to take a smaller piece of a bigger pie.”

ClassPass argued that the two algorithms, together known as SmartTools, often led to 15 to 25 percent increases in revenue and 30 percent increases in reservation volume. To try and convince some skeptical partners to switch over, ClassPass guaranteed a certain amount of revenue, and told VICE the “vast majority” of studio owners received guarantees higher than what they had previously been making. Burrows said her guarantee was in fact less than her previous revenue totals. But there was another, more pressing problem: Dynamic pricing required studios to agree to rock-bottom rates that made her uncomfortable.

“In some cases for pilates, I would literally, like, literally be losing money per visit because of what the teacher gets paid—not even including the rent and marketing and keeping the lights on,” Burrows said. “In the case of yoga, although I wouldn't be losing money, the earnings were so low and my margin is so tight that in terms of all the expenses that we pay to run the studio, I had to say, are you smoking? What, are you on acid?”

Menaker said that if a studio could prove that a “proposed rate floor was not capable of generating profitable revenue for that studio,” ClassPass would raise it, and noted that ClassPass and studios mutually agreed on the price floor. But ClassPass could not promise partners what their “future average rates” would be, and studio owners said they felt pressured by ClassPass to drop the price below what made them comfortable.

To Menaker, studios focusing on the low rate floors missed the point: There was “no concerted effort” to hit a target floor rate of any number. Rather, low floors allowed the algorithm to best search for the price that would bring in the most total revenue.

Core to the switch was ClassPass convincing studios that the algorithms worked. But whether they did work wasn’t clear. “There's a total lack of transparency on their part,” said Hauskens, who added Remedy Barre + Foam Rolling “never knew how they determined what the value of our classes were.” “No one can ever give you a straight answer on why you made the money that you did that week,” said one New York City owner. (“We provide studios with clear payout distributions so they can see how they are performing and where their revenue is coming from,” Menaker said.)

As it had discussed internally in 2016, ClassPass moved ahead on shifting the conversation with partners toward “overall revenue” rather than “rate per class,” according to internal emails and conversations with studio owners.

Bonnie Bell, the owner of The Sweat Shop in Missoula, Montana, estimated that between one-third to one-half of her customers come through ClassPass today. Bell’s minimum rate is $8.70, less than half of her drop-in rate of $20. But in Missoula, where the cost of living is significantly lower than in a coastal city like New York, her goal is just to get $10 per person, and she has also regularly seen increases in monthly ClassPass-related revenue and memberships while using SmartTools.

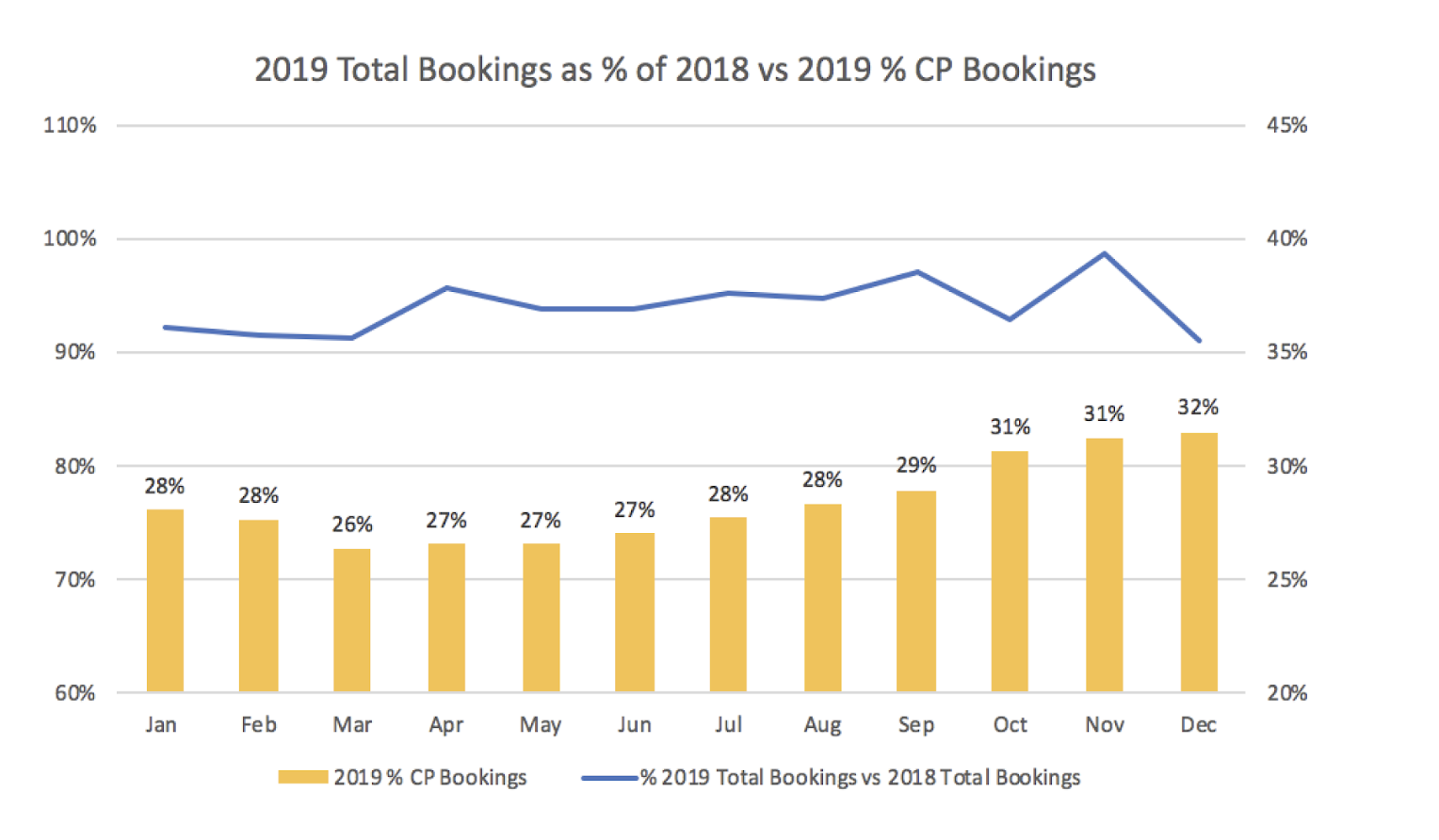

As long as ClassPass-related revenue was growing, why did it matter what the rates were? At Yoga Vida, the reason became clear around April 2018, when ClassPass cancelled its contract with the yoga chain and pressured it into a new agreement that required dynamic pricing, according to Yoga Vida co-founder Michael Patton. From that point forward, ClassPass took hold of a growing percentage of Yoga Vida’s business with little to no benefit to the yoga company, Patton claimed.

While Yoga Vida’s average ClassPass rate dropped 11 percent to less than $12 between 2018 and 2019, the total amount of money ClassPass paid the yoga chain increased by only 3 percent (as a result of an increase in volume). “Their algorithm should perform in a way that we're making more money for the same amount of work. Or, if we do a little bit more volume, we should make an incrementally little bit more revenue,” Patton said. “We [had] to work harder and do more volume every year to be able to make the same amount.

“That, to me, is not maximizing revenue,” Patton added. “That's just maximizing volume for ClassPass.”

What Yoga Vida did get was 8,000 more visits from ClassPass users, who made up an ever-growing percentage of the business. I was among them. I had originally signed up directly through Yoga Vida for a $30 unlimited trial. When that was finished, I started to come regularly through ClassPass because it was cheaper. Patton allowed me to look at how much Yoga Vida had been paid for the classes I took—$7.90 for one class; $8 for another. For one Saturday morning class I attended in April 2019, Patton’s company only received $12.70. The studio was typically charging non-ClassPass customers around $17-18 at that time, and Patton said more and more former Yoga Vida students were starting to arrive through the ClassPass platform, which Patton described as “their cannibalization of existing users”—exactly what ClassPass said it didn’t do.

Other businesses said they also experienced negative consequences after instituting SmartTools, unintended or otherwise. One Los Angeles studio owner said he was “basically strong-armed” into trying out SmartTools on a trial basis and came to the same conclusion.

“I tried it for three weeks, looked at how we were getting paid, and I was like ‘We're not getting paid enough for these peak-time slot classes,'” the studio owner said.

In November, Kadakia indicated that the worst was behind the company. "A lot of the friction and constraints we've had, we've been able to get over,” she said.

A few months before, ClassPass had been sending more stern messages to its partners. One of the New York City owners said that ClassPass suddenly reduced the number of manually selected premium spots in his classes over summer and told him in so many words: “You either sign this [SmartTools] contract… or we're gonna have to reevaluate our relationship.” In late 2019, ClassPass proposed a 2020 rate as low as $7 per student at Yoga Vida, which made Patton furious.

“It feels like they're trying to get away with as much as they can without pissing studios off to the point where they do depart,” Patton said.

Then, in December, the company sent out an email to older partners informing them that the new era of ClassPass was commencing whether they liked it or not.

“Starting on Monday, December 9th, SmartSpot will be turned on for all of your schedules,” the company wrote in an email. “SmartSpot, is designed to look at your fill history and your real-time reservations to predict the spots you’re not likely to fill directly and automatically list them with ClassPass. The goal? To save you time and legwork by automatically releasing inventory.”

Soon after, ClassPass issued another “important update”—this one about user data. Studios would no longer be able to use ClassPass customer contact info to try to convert them to regulars and would have to obtain it themselves. The announcement was timed with the arrival of the California Consumer Privacy Act, and amounted to ClassPass instituting a required state rule nationally—a move that was not unreasonable, but to studios was unwelcome.

ClassPass had originally promised partners easy, free marketing and control over how many ClassPassers came into their classes and how much they were paid per person. Now the studio owners felt ClassPass had officially stripped control of their own prices and inventory from them—and any hope of converting ClassPass students to studio regulars.

“They’ve taken control,” said Acker, who said it seemed as if ClassPass was “essentially renting out spots in our classes and making the customers their customers, not our customers.”

Hauskens said ClassPass tried to get her to sign an electronic document agreeing to switch over to SmartTools but that she and her business partner refused to do so. She said the per-person rates ClassPass requested were as low as $7, the same rate Yoga Vida had been offered. “That's just barely breaking even in our business,” Hauskens said. ClassPass told her the company would not switch her over in January.

“And then January rolled around, and they changed us anyway,” she said. “We had to call them and tell them to revert us back and [while they did,] our account manager gave us nothing but attitude.”

ClassPass said concerns about them taking over studios’ inventory are overstated. “We actually hear mostly the opposite, which is that the algorithm is not aggressive enough and leaving too much money on the table,” Menaker said. “In response, we have introduced controls for partners that allow them to increase SmartSpot’s aggressiveness as partners were telling us it was too conservative.”

In cases where SmartSpot is taking spots that would have otherwise gone to direct customers, ClassPass said it would “adjust the algorithm or disable SmartSpot.” “We will always work with a partner to find a solution that is mutually beneficial,” Menaker said.

For some, the algorithms are working well. Bell, the founder of the The Sweat Shop in Missoula, said her ClassPass revenue is up 72 percent in January and that more than half of her ClassPass users this month are new to the platform.

Others elsewhere haven’t been so lucky. “They can send us as many students as they want at whatever price they want, and we have absolutely no control over it,” said one New York studio owner now on the SmartTools platform. (ClassPass said it will never pay studios at rates below predetermined floors.)

In 2020, ClassPass has met SmartTools-related revenue promises at the New York owner’s studio by “basically just flooding our studio with low-price reservations, which is also pissing off all of our fully paying customers,” the owner said.

Three weeks into January, the studio had taken in 25 percent more ClassPass reservations than it had one year prior, but the amount of ClassPass revenue the studio received was down 30 percent, or $7,000, because ClassPass cut the per-student average nearly in half to below $10 per student. The dramatic price drop has caused an ever-growing number of former direct customers to convert to ClassPass users there as well—one reason the studio's overall revenue dropped by 17 percent year over year.

ClassPass said the studio owner’s situation is an outlier, telling VICE that its internal metrics showed only 32 of its 890 New York City partners “saw reservations increase while revenue declined” in January and a low percentage of partners more generally experienced a revenue decline when they switched to SmartTools. (VICE was not able to confirm these numbers.)

For the owners who are struggling, the statistics are of little comfort.

“We can't pay our teachers,” the owner said. “We can't pay our front desk staff.” It felt as if ClassPass “suddenly pulled the rug out on very, very short notice.” “They promised all sorts of controls that they then abruptly took away after they got studios and their students kind of hooked."

“We don't have control this year, not by choice,” said another exasperated New York studio owner. “And it hurts. It just really hurts.”

Both said they felt they lacked the reach and market share to walk away.

“We have 30,000 studios and have only received a small number of complaints about SmartTools,” Menaker said.

In metropolitan areas where the cost of living is high, small fitness studios are quietly undergoing a crisis. Corinne Wainer, who co-founded SHAKTIBARRE with her business partner Shauny Lamba in New York City, said she recently had to close one of her studios “because while we had pretty standard numbers for a new location, less and less students were our direct members. We began to research some reasons why.” In late December, Jivamukti was forced to close the doors of its New York City studio as well. The Yoga Journal called it “The End of an Era for NYC Yoga.”

“Every three or four weeks I get an email from someone: Take over my lease, I'm bleeding and I can't survive anymore,” one of the New York owners said.

ClassPass alone is not to blame for the industry’s struggles. Rising rents, wage increases and the newly enacted California’s Assembly Bill 5, which requires businesses to extend traditional benefits to more of their employees, are all concerns for small studios in their own right. Menaker pointed to another issue too: industry saturation, noting that the number of New York City studios on ClassPass doubled last year alone (whether or not ClassPass contributed to that saturation depends on whom you ask).

VICE spoke to an array of studio owners around the country. Outside of those provided by ClassPass, almost all of them said they had concrete frustrations with the company. The administrators of Jivamukti Yoga Center, which still has dozens of thriving international locations, said that ClassPass played an inarguable role in the closing of their large New York studio—and warned ClassPass could end up “cannibalizing their own business model” should the company continue on its current course.

Lanman said he has empathy for the studio owners who spoke to VICE, but that they are part of a “vocal minority.”

“They are facing a ton of competition,” Lanman said. “I don't think the majority of this pain is coming from ClassPass.”

As of today, ClassPass has taken in more than half a billion dollars in investment, which means it will likely have to prove its profitability while simultaneously raising its value higher to please the type of investors who typically search for exponential returns, according to Bradley Tusk, a venture capitalist and founder of Tusk Ventures.

“The priority up until now [in the technology business] has been growth at all costs. And companies were encouraged to do whatever it took to grow and not to worry about profitability,” Tusk said. “Now everything has flipped.”

“If you look at Uber and WeWork and Pinterest and a few of the other IPOs, they all suffered or didn't even happen because the market was unwilling to put hyper-growth way ahead of actual profitability,” Tusk added. “I'm sure ClassPass knows that they have to do that, which is why they're starting to tighten the screws on the individual studios.”

ClassPass insists this is not the case, and that the model is working for both the company and most of its partners, pointing to its 90 percent retention rate among partners with “regular reservation volume.” The company is not profitable, but only because it invests so heavily in marketing and technology, the company said.

The studio owners themselves feel less confident in their own prospects.

“You're spending your blood, sweat and tears,” one exasperated New York studio owner said. “The only thing they're doing is selling a cheaper price. They don't own a space. There's nothing that they do.”

A growing number of studio owners are taking a harder look at how to survive in the age of ClassPass. In January, both co-founders wrote on SHAKTIBARRE's Instagram that they were "torn” about staying on ClassPass as one outcome of their research: “We adore our ClassPass students and yet — the CP business model has changed so drastically in the last few years that we’re unsure if it’ll sustain us.”

Tursi still doesn’t “feel comfortable ending the relationship because all the other studios are on it.” Neither does Hauskens, who said it would be hard to walk away from the thousands of dollars her studio receives from ClassPass every month.

“At this point, we're kind of between a rock and a hard place,” Hauskens said. “It's like being hooked on a drug or something.” (Menaker said “small businesses who build an entire marketing strategy around one channel do not set themselves up for success.”)

Tursi doesn’t see the company as evil. “I understand that they are in business too. It’s hard for everyone but I believe there is a way to work together,” she said. Other studio owners are wondering if there’s another path. “If several other multi-location studios would also go off [the platform], then suddenly ClassPass would have a major inventory problem,” one of the New York City studio owners said. “This whole thing could collapse in a day, just like the Berlin Wall.”

Some people are already taking the plunge. Yoga Vida had been partners with ClassPass since 2013. Patton told VICE he didn’t want to pull Yoga Vida from ClassPass. If the company simply took a commission, but allowed the yoga chain control over price and inventory like in the early days, he’d probably still be on the platform. Now he’s worried about other studios like his.

“If ClassPass gains complete control over studio inventory, and continues to put downward pressure on price, then there is nothing that will save us,” he said.

In late December, Acker’s studio, Love Story Yoga, joined Yoga Vida in formally ending its relationship with ClassPass. By the time Acker left, the average rate he was receiving from a ClassPass visit was around $10.20. Acker felt strongly that many of the people coming through ClassPass would come anyway. “They were coming on ClassPass because it was just a cheaper pricing option,” he said. But for Acker, it was also about more than the numbers.

“All of it coalesced into them taking control of our business,” Acker said. “And there's no way in which they're going to run our business in our best interest.”

Last year, Burrows tired of ClassPass’s dominance over her studio too. “I just thought to myself, you know, this is just like a parasite and it's only going to get worse,” she said. Burrows had a third-party company run an analysis that helped her figure out that many of her ClassPass attendees only visited The Pad and one other—meaning she had more customer loyalty than ClassPass had led her to believe. (ClassPass denied this characterization of Burrows’ ClassPass client base.) “They spin this myth that they bring so many people to your studio. And that’s just not the whole story,” Burrows said. “These people have been coming to our studio for two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight years. They're not just going to all of a sudden stop coming.”

While on her way out, Burrows took one simple idea from ClassPass—she started charging a little less per class in exchange for a mini-membership.

Burrows said she’s already seeing her revenue stabilize and recover. After she made the decision to leave the platform, she heard from a lot of other studio owners too.

“Everybody said, ‘We are so fed up, it's no longer working for us. The contract makes no sense. It will kill our business,’" Burrows said.

And then, she said, they all asked her some form of the same question: How did you do it?

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Maxwell Strachan on Twitter .

from VICE https://ift.tt/2ufGjxy

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment