“Someone please get the guys who made cartridge games a cigarette and a blindfold” proclaimed a magazine ad, emblazoned with one of Final Fantasy VII’s impressive panoramas. The better future was not only arriving, it was executing the past. As Cloud leapt off a train in FF7’s opening cutscene, he was leaping into the future of gaming. In this moment, it seamlessly transitioned from video to play. The line between interactivity and film was blurred into non-existence.

FF7’s ambition to blockbuster status was emblazoned on the frayed film strip on its game over screen and its lavish, indulgent cutscenes—and none of it works anymore. You can see the frame rate hitch as it switches from a video file to the game proper. Cloud’s chunky arms probably never felt like a revolution, but now they are downright silly. His facial expressions are blurred, never given the immediacy or intimacy that film can provide. Though the cutscenes are somewhat “cinematic,” in the video game, Uncharted sense, the rest of the game’s storytelling is old school. Text boxes are the only means of dialog. FF7’s cinematic vision feels hampered by the aspect ratios and animation fidelity of 1997. It shows its age.

However, even in 2020, the original Final Fantasy VII feels purposeful and vital. With all the hype of its context stripped away, craft remains. The insistence on fixed backgrounds, undoubtedly done to enable greater levels of fidelity and detail, results in something uniquely fractured and cinematic.

The game proper, and thus most of the explicit narrative, plays on pre-rendered backgrounds. For the unfamiliar, a pre-rendered background is like a photograph upon which the digital actors play. In contrast, fights are on small scale grids, where recognizably human figures wage war on tiny battlefields. There are cutscenes where extended sections are text alone. Submarine piloting, snowboarding, Chocobo riding, and motorcycle mini-games all interrupt regular play. FF7’s perspective shifts constantly. While one might expect those shifts in a minigame, the game still cuts constantly. Not only from battle to exploration, or from the world map to a town, but from individual parts of a location. The player has no control over what they see, rather the game always controls the camera. It represents a space that we move through, but whose perspective we cannot shift. FF7’s interactive cinematography feels both fractured and connected. It forces the players, and the characters, to see themselves at multiple angles.

The camera places its characters inside of massive environments, both manufactured and natural. In the first five minutes after Cloud steps off the train, the camera tilts up. A reactor, stamped with a corporate marker, dwarfs his polygonal frame. While the player controls Cloud and crew, the massive power plants, decaying villages, and crystal oceans are the game’s principle characters. From the first of its frames to its last cutscene, FF7 grounds its environmentalism in the overwhelming scale of the natural and artificial world.

In both visual and narrative terms, the player finds themselves caught between massive forces, only a small spark in the face of incredible power. Cloud and the eco-terrorist cell Avalanche operate out of a bar in the slums of Midgar. Their foe, Shinra Corp., acts as the de-facto government and corporate monopoly. Their journey to end Shinra’s rule escalates to a quest to stop imminent climate collapse. As these characters move through the world, we see how their individual traumas are tied up with the planet’s life and why they choose to fight for the environment. Through constant exploration, the planet’s body reveals its connection to mankind. At the game’s climax, it even has a heart. The planet’s loss is our own.

FF7 lets its characters be small in a way that is rare in 3D video games. Often huge factories, gigantic cliff sides, and massive caverns swallow Cloud. As he and the rest of Avalanche move through the reactor they will destroy, the machinery continues to tower over them. In one scene, the camera overlooks a platform in a center of the complex. It frames a vast and unknowable machine. Impossible to reach scaffolds and staircases haunt the edges of the screen. As Cloud descends, platforms, pipes, and machinery obscure him. Even in the more intimate scenes, such as when Cloud and his boss Barret argue in an elevator, the wires and lights of industry encroach on their space. It is imagery as literal and pointed as Charlie Chaplin crushed between gears. Shinra is a machine that consumes everything. Cloud cannot escape his environment, nor can he be an avatar for the player’s whims, not as long as his perspective cannot shift the environment’s. Even as Avalanche blows up the reactor, they must run into the city, where they are as small as any other citizen and even more endangered.

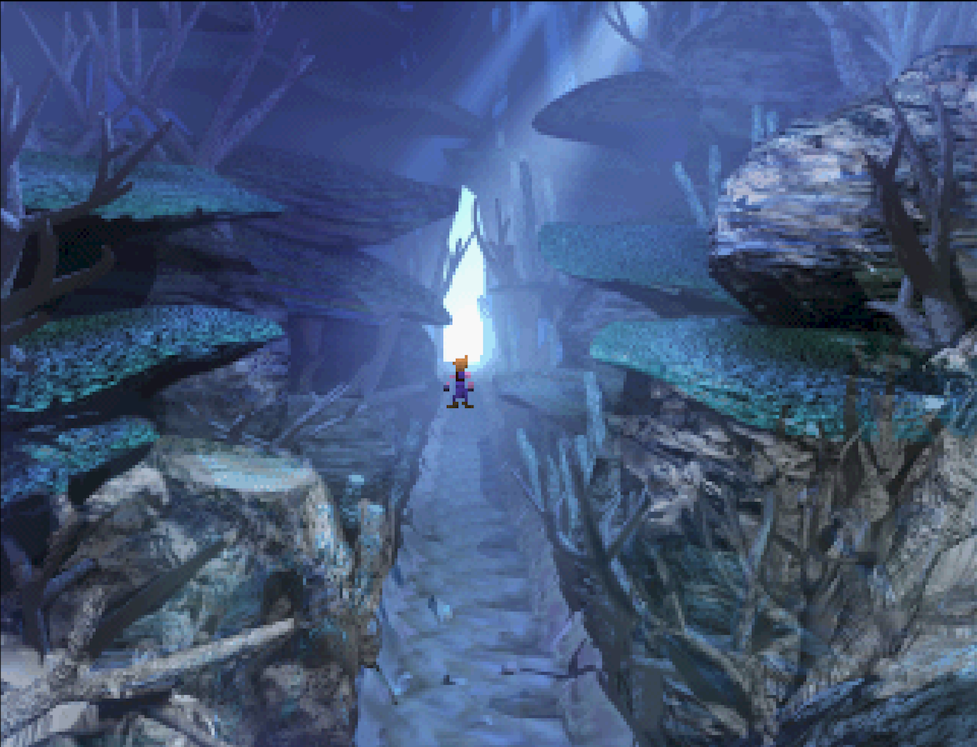

However, as Shinra’s grip on power becomes shakier, the forces of the earth wake up. Nature’s threat, and the necessity of co-existence, layer themselves in most of FF7’s frames. As Cloud’s party walks through ancient villages, they find a harmonious bond with nature not seen in Midgar. They explore abandoned houses inside giant seashells, rocky homes layered into cliffs, and cities expanding around coral. The world untouched by corporate greed is dead, but lingers, reflecting nature’s ability to transform beyond mankind’s simple imaginations. As Cloud enters the core of a long vanished culture’s city, the blue coral color of ancient oceans envelopes him. Cloud is just as small here as he was among Shinra’s machinery. The powers of earth are old and strange. They will outlive our frail bodies. Even the valleys and cliff-sides where Shinra reactors stake their claim are framed by nature’s might. Though one reactor’s smokey tower looms over an ant-like Cloud, who snakes his way along a mountain path, the cliffs and trees of the valley still preside over the scene. The promise of every open world is that you can go to that mountain; FF7 gives that mountain presence and power. One does not simply walk there.

In contrast, most modern games of FF7’s budget and scale are individualistic. Most cameras follow a single character and give the player full control to frame their environment. The shot might be wide or close. The player character might seem small or loom large. The exact nature of this perspective varies from first-person shooter to open world RPG, but all of them are singular. Often this is done in the name of consistency or immersion. The player identifies with a single character, decidedly not their companions or environment. God of War took it even one step further, touting the craft it took to never look away from its protagonist. The result is a gaming language best suited to expression of power. When Kratos’s body dominates every frame, the game’s world and its characters cannot help but shape themselves around him. This perspective represents a singular, seamless, empowerment. The world is never outside the player’s reach.

FF7 is not seamless and, often, not empowering. It flips between styles and shots and tones. The controls change with each of its different modes, even between the screens of a location. Playing it requires consistent awareness and reconfiguration. Its world is interconnected, but not continuous or uninterrupted. Rather it is fractured, suggestive, and strange. We lose sight of ourselves in the coral reefs and power plants. They have hidden corners that neither cameras or players will ever reach. This holistic view reflects a wild world, both threatened and threatening. It is a vivid, multi-framed portrait of a dying planet. In cinematics and cutscenes, its character can gain power in the frame. For example, one of FF7’s final moments is an outstretched hand. However, the game never lets that perspective be singular, always returning to the world outside.

Since it came out, it seems we’ve learned the wrong lessons from FF7. Since the Resident Evil 4 made the jump to seamless camerawork, the rest of the industry, including Final Fantasies since, have made that same jump. Games with the scale and budget of FF7, also with fixed camera angles and fractured storytelling, are rarer than ever this generation. Thus the remake must reckon with the tensions between modern trends and its source material.

At the game’s beginning, there are many callbacks to the original. Cloud stands before the reactor, argues with Barret in the elevator, and climbs down into the same underbelly. But in this version, Cloud’s figure looms almost as large as the reactor, the elevator is well lit and flatly designed, and the environments easily readable. They are meant to be traversed, meant to be fought through. So, the environment loses its looming threat and omnipresence. The cold sheen of modern gaming replaces the fractured visual language of the original.

The remake completely leaves behind smallness and scale, opting instead for the continuous identification of almost every open world RPG. When Cloud swings off the train, he is not an individual throwing himself against Shinra’s might, but another badass avatar. Final Fantasy VII Remake’s individualist perspective shows how vital the original’s fractured cinematography was, and how little of its dying planet the modern game industry can perceive.

from VICE https://ift.tt/3aXWI9F

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment