At the end of March, the Wall Street Journal published an opinion article from a Stanford professor of psychiatry titled: "We All Need OCD Now." He wrote that one of his patients with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) didn’t need the push from a viral pandemic to practice good hand-washing habits, nor to be careful of contamination from surfaces and inanimate objects. “We can look to people like my patient for discipline and inspiration,” the psychiatrist wrote. “A little OCD, right now, wouldn’t be so bad.”

The article ticked off a lot of people who actually have OCD—myself included—whose anxieties are not a boon, but have interfered substantially with daily life, disrupting work, travel, and our personal lives.

Yet, I’ll admit that OCD can be tricky to talk about, often because it mirrors behaviors that aren’t problematic when done in different contexts. Obsessions and compulsions can also morph throughout a person’s life—being dominant and overwhelming at one period, and just a low background hum at others. Obsessions can be invisible thoughts instead of behaviors, and difficult to explain why they’re so troublesome and overwhelming.

A new illustrated book by New Yorker cartoonist Jason Adam Katzenstein, Everything is an Emergency: An OCD Story in Words and Pictures, out on June 30, is one of the best representations I’ve ever read of what it’s really like to have an OCD brain, with all this nuance captured.

It tells Katzenstein’s history with OCD, from his first odd, ambiguous childhood fear—a statue in his grandparent’s house—to his struggles a fear of germs and contamination, magical thinking about everyday household objects, relationship obsessions, and more. Unlike an "I’m so OCD" joke, when someone co-opts the diagnosis to justify a penchant for tidiness, Katzenstein’s book reveals the experience of being bombarded with intrusive thoughts day in and day out.

It also provides a glimmer of hope. Katzenstein describes how he finally did a challenging therapy called Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP),where a person with OCD exposes themselves to their worst fears, and it helps him. Along with his OCD story, he draws and narrates selling his first cartoon to The New Yorker, living in the big city (with all the grime and mess that comes with it), dating, and learning how to rely on friends and family for support with his mental health.

I had planned on talking to Katzenstein about the book before the pandemic hit, but we decided to move up the interview. While the Wall Street Journal incorrectly framed OCD compulsions as something net positive, there is something interesting about being a person living with OCD during this time period.

In some ways, our worst fears are coming true: People all around us are behaving and acting similarly to our compulsions and reflecting our anxieties back at us. There is a crushing sense of uncertainty about when the pandemic will end, and how we’ll all be affected—uncertainty and doubt are core to the anxieties that rule OCD. But for those of us in treatment, we’ve also developed a lot of coping mechanisms to deal with the very worries that are permeating daily life.

OCD is about feeling anxiety in the absence of real danger, and yet—there is a real danger. It's much more complicated than just: OCD people are faring worse or OCD people are faring better than people without it right now.

Katzenstein and I chatted about all this complexity, and how it feels for him and I—two people with OCD—during a pandemic.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Shayla Love: Why did you want to write about your experience with OCD?

Jason Adam Katzenstein: I didn't always like to talk about it. It felt quite scary and lonely. I was pretty ashamed when I was younger. I got my diagnosis when I was 15. The material that I found on OCD were testimonials that were really scary or very dry workbook-type things. There was nothing to temper a lot of that initial fear. I felt condemned to have this thing that never goes away. I didn't really understand that it can be better or worse, or that managing it can mitigate a lot of the pain associated with it. And so I wanted to make the book that I could have found then.

SL: You capture this really well in the book: compulsions and obsessions can change a lot and look and feel differently at various points in your life. They can come and go. For me, contamination and health anxieties have always been a dominant concern, and you write about your own contamination fears. At the beginning of the pandemic, I was worried that this would bring it all back. Did you feel the same way?

JAK: Yes and no. For me, it's not always like OCD is rational. It doesn’t respond proportionally to real crises. Since OCD is a game that my brain is playing, I didn’t know what to expect. Sometimes minor things feel huge and sometimes catastrophic things feel manageable. Do you know about flooding?

SL: I don’t think so.

JAK: Flooding is a tactic I learned from a therapist where, instead of doing a progressively more intense hierarchy of exposures [to things that make you anxious] you do something really intense that's also impossible to undo, a shock to the system. Let's say I was afraid of pasta, I would just cover my bed in pasta, then not wash the sheets.

I didn’t know what would happen with contamination stuff because this feels like a flood. But what I’ve found with OCD is if I need to manage a situation, I will. It’s almost when there’s less to do, when there is less work to attend to, sometimes that’s when my brain gets more creative coming up with what terrible catastrophes could be happening.

SL: My worry was that a viral pandemic fits with the concept of contamination I have in my mind, which is something invisible that can be everywhere. With contamination fears, it's not about just literal dirtiness: It's this pervasive, general conception of contamination. A pandemic feels vulnerable to that mindset.

That said, one of the reasons I was so frustrated with the Wall Street Journal article is that I realized that OCD is having that anxiety in the absence of danger. Whereas, here, there's a real danger going on. OCD has so much to do with doubt. We don't know how this is all going to end, but it’s certain that it's happening. Yes, there are a lot of potential OCD triggers from the pandemic, but I've found myself wondering if OCD has anything to do with it.

JAK: My most generous read on that Wall Street Journal article is that one thing that you and I are probably equipped with is having techniques to manage anxiety. I'm really editorializing beyond what the article said, but I was talking to a friend about this. I was like, 'Man, I've been in a good place for awhile, and I can't believe that this is happening.' He said, 'But imagine if you didn't have all these coping mechanisms, how you'd be doing right now,"—which is a great point.

What I've learned through exposure therapy—not to mention how much better my brain feels because of the Zoloft, [that] has very much come in handy—like, we should identify when a train of thought extends beyond the scope of what is known and to what is theoretical. It's good to know where that line is.

I've found that I've been the reassuring one [to friends] lately because even though I've had to learn these tactics for things that haven't actually been emergencies, it turns out that they also work during what is absolutely an emergency.

What you said about not feeling a big spiking in your OCD that makes sense too. Have you read articles about people talking about how their anxiety is being mitigated by the pitch being higher on everybody's anxiety?

SL: I was talking to somebody I work with about this, regarding depression. He was saying how everybody seems depressed and how weirdly, he actually feels better. I think it's because the gap between us and “normal” people has shrunk a lot.

JAK: There’s the first-order feelings of depression, anxiety, OCD. And then there’s the second order, like self-flagellation and judgment, feeling like [you're] the other. With contamination, it’s not just I can’t touch this. It’s: I can't touch this and everybody's gonna think I'm weird at the party. Those second-order feelings fall away when you feel like your reaction to the world is more in harmony with everybody else's.

That said, I would not wish this feeling upon anybody. I’ve had people, like my dad, say, 'Is this how you feel all the time?' And kind of, yea. But I don’t want him to feel that way—I don't want everybody else to walk around feeling as afraid of contamination as I've been.

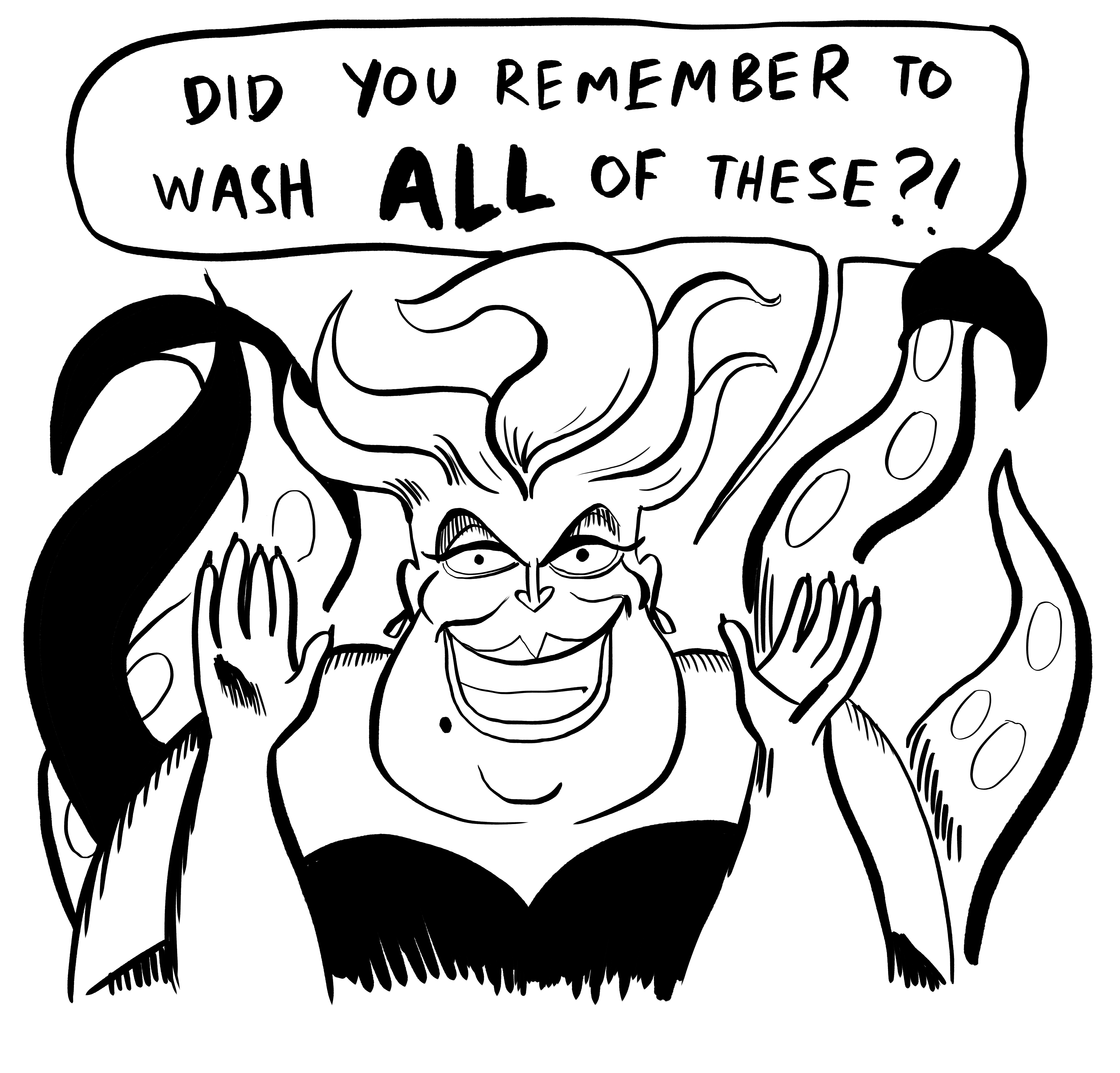

SL: You talk in your book about being told to name your OCD. A therapist told me once to choose a Disney villain and have my OCD thoughts come from them—to externalize that voice from your own. I kind of feel like that's what's happening here too. The pandemic is the villain and it's spouting these ideas, that you're not safe, everything you touch is dirty. But in a way separated out from me and my brain: There’s this external bad guy that's making everything unsafe and it's not coming from me.

JAK: I completely buy that. It's important for me to separate things from my own sense of self whenever possible. A lot of this book was trying to untangle which parts of this are me, and which parts are anxiety. Which Disney villain did you choose?

SL: I picked Ursula.

JAK: Oh man. Ursula's great. I don't think she's a villain.

SL: Maybe she’s not. I really like her voice. it was between her and Maleficent, but I went with Ursula.

JAK: I once made my OCD a monster named Marvin. The way I've regarded my OCD is constantly in flux and sometimes it's a separate entity, sometimes it's me in different clothes, sometimes it’s me but as a cartoon, and then sometimes it's a non-entity.

SL: While my contamination OCD hasn’t really spiked, at the beginning [of the pandemic] especially I was taking the social distancing rules really, really seriously. Feeling a lot of personal responsibility. If I walked down the street and there was somebody less than six feet away from me, I felt really bad.

JAK: That has absolutely been the theme that has been blowing up for me. I haven't gone outside too much, but I feel guilty about those early days before things were set in stone and things were still open. I felt guilty about being in my coffee shop, going over to a restaurant.

The other day, I got a package and I went downstairs and opened my door. I wasn't wearing a mask cause I wasn't leaving my apartment, but then thought, 'Oh no, we're standing less than six feet away from each other,' and the person who had delivered the package was wearing a mask. I ruminated on that for a while.

At the heart of both the guilt and responsibility spikes that I have—and the contamination ones—is an underlying fear that I am disgusting and nobody should want to be around me. And if people did make the mistake of being around me, they will suffer. I will hurt them, I'll put them in danger. In a moment where nobody wants to be around each other and the stakes really are that you can put people in harm's way by being close to them at all…it comes up.

SL: I’ve also imagined my parents or people that I know getting it and having to be put on ventilators and dying. The thought process goes: Why would somebody that I know not get it and die when other people have loved ones who do get it and die?

JAK: I hear you. Would you categorize that as an OCD thought pattern or do you think that's just rational?

SL: I think about this distinction a lot. I often used to ask my therapist if my behavior or thoughts were toeing the line of rational. Right now, when a lot of people are having these same thoughts, it’s hard to tell. I always hesitate to pathologize everything.

I know my brain is wired to be more anxious than others and I definitely have OCD. But worrying about whether or not your friend is going to get COVID-19 is a rational thought, I think? For me the OCD part comes in when I'm visualizing them on a ventilator for three hours a day. It's about quantity and interference.

JAK: Rational versus irrational is one rubric and sometimes not the most helpful because OCD always has a toehold in reality. The stakes with OCD can often be real. There is some rationality to the fears and then it's just that we have the tendency perhaps to be hyper-vigilant and vigilant beyond what is helpful to us.

Also, I think everyone I've ever spoken to who's dealing with OCD also questions whether their OCD thoughts are or are not OCD. One tactic I've learned is if you think it's OCD, it is OCD—which has been more helpful than I could have imagined.

SL: One of the tenets I try to live by is to challenge my anxiety in small ways every day, but it's hard to do that when you are just staying home. I feel really safe and comfortable in my home. So I feel pretty unchallenged and I’ve been thinking about the ramifications of that when this is over.

JAK: I hear you. There's the opportunity to get creative about exposures: I've written scripts in the past that simulated a dangerous situation. Or you can imagine it. Wash a piece of fruit, but then pretend that you didn't.

It’s just a difficult time for exposure therapy. Unfortunately, I think that means some of that work will be put on hold. But I don't think that means that that muscle will atrophy because I mean, who knows what happens after this. One thing I can imagine is that when there's a vaccine for COVID-19, god willing in a year or as quickly as possible, some of that danger might no longer exist. I could imagine going into a grocery store and no longer feeling any anxiety at all about touching anything or bumping into people because the stakes have suddenly gotten so much lower.

This could be kind of like training in high gravity. We could look at this as like an incubation-slash-training period, an extended exposure if we can get through this, then a lot of the contamination stuff that used to be worrisome might feel less so.

SL: You said that you want to separate out OCD from your sense of self. I have this conflicting mindset where part of me feels it's not everything that I am. But then I also have moments where I think: well, it does color the way I think and the way my brain works. You’ve said that people ask you: do you feel this way all the time? I would say even on really, really good days, I still feel this way. So, I have a conflicted sense of how big a part of my identity it is.

JAK: I'm just beginning to try to untangle that question because one refrain that I've gotten a lot in therapy is to say, ‘It's not me, it's my OCD.’ When I first heard that as a teenager, I felt a lot of pushback. I was like, but it is me.

At the Center for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, where I've been going for a few years, they really confront that head on. It feels a little woo woo, but we talk about our life's path. Like, what do I want, what are my goals, what are my values?

Then there are two terms I learned about: ego-syntonic versus ego-dystonic. Sometimes an OCD thought will be like, “Man, I really don't want to infect somebody else with a disease.” This could be an OCD thought, but it's ego-syntonic in that it's in line with my values, which are not to hurt other people. A dystonic thought would be: I am the worst person on earth. And I don't want to be the worst person on earth.

So I guess OCD is a huge part of who I am, but it also sometimes gets in the way of who I want to be. But then a part of who I am gets to be coping with that, if that makes sense. I think it’s going to be a lifelong question, something that’s always ambient.

Have you seen A Beautiful Mind? Terrifying movie. There's a part in that movie near the end where he seems like he's doing better and he gives a speech and then somebody afterwards asks: "Are the people still there?" And they're kind of in the distance waving. I think about that. I'm like, “Okay, yeah, on a good day, OCD is in the distance, waving.”

SL: Something that makes me less scared of those people in the distance always waving at you is talking to other people with OCD. I think that was like a big turning point for me. I went to one of the International OCD Foundation conferences and they have this thing called the “room brigade.” If you go to the conference but then you get stuck in your hotel room by anxious thoughts or compulsions, you can call the room brigade and a group of people will help you leave your room.

I've been thinking about that a lot with the pandemic, how we're all sort of in our rooms alone. But I think we have virtual versions of the Room Brigade connecting with other anxious people or ones that you love and still making sure that we all get out of our heads.

JAK: I love the room brigade.

SL: It’s such a perfect name, because it makes it sound so noble.

JAK: It is noble!

SL: Like white knights on horses coming to help you.

Any final thoughts for people with and without OCD who are finding this experience to be really stressful and really anxiety inducing?

JAK: It's probably good to be really clear-eyed about how this is a really scary time and a lot of people are going to be feeling very uncertain, and a lot of people will be vulnerable to the worst of this. To pretend that that's not true—it is not a good way to cope.

That said, after an honest appraisal of the situation at hand, I hope that nobody feels guilty for taking care of themselves right now. I hope nobody feels like they have to be productive. By that I mean that I think that the expectations on people to work above and beyond what should be humanely expected of them at any point is unconscionable.

Now, I'm rambling… I guess get enough sleep, eat meals on a schedule, exercise, take deep breaths, talk to the people you love. We really are all in this together. Are these platitudes? I don't know.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Shayla Love on Twitter.

from VICE https://ift.tt/2VNq5Xm

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment