Whether we like it or not, every game comes with its own expectations. When you jump into any online lobby, you enter into a sort of social contract—everyone in the sessions agrees to play to the best of their abilities to win the battle, or race, or round of fantasy wizard chess. Push hard enough, though, and those expectations quickly come tumbling down. In Splatoon 2, all it takes is a good paintbrush, a few friends, and a willingness to break a few rules.

I’ve been playing a lot of Splatoon lately. Like, a whole lot. Practically nothing else. But in the last few months, diving into a Turf War looks more and more like this: flapping around spawn like beached fish, leaping into the air while hollering “booyah!” Lean into the chaos enough, and the other team might even get in on the action.

Maybe this is just a bunch of strangers coming together to goof off. There’s certainly no end to disgruntled players complaining about so-called “squidparties”.But I’d argue there’s something deeply radical about all this nonsense. By rejecting the game’s expectations, Splatoon 2’s squid kids have given me a little bit of connection in a world that can—both online and off—feel lonelier than ever.

Whether for political protest, artistic expression or just goofing around, breaking gameplay conventions is nothing new. In 2002, Anne-Marie Schleiner and Joan Leandre’s Velvet Strike used Counter-Strike as a means of anti-war protest in the aftermath of 9/11. Robin Klengel & Leonhard Müllner’s 2019 short film Operation Jane Walk, meanwhile, offers a pacifist tour of The Division’s New York City that explores the intersections of history, architecture and urbanism—and the places where Ubisoft’s combat needs shear through those threads.

For me, it’s always been about finding some lost sense of community. Oh, It’s not hard to find a Discord or a Subreddit for any given title. But hanging out in the game space itself? That’s something I’ve increasingly come to miss.

As games leant further into competition, those social spaces were increasingly left behind. In an Errant Signal video comparing the social climates of TF2 and Overwatch, Chris Franklin notes how the latter is far more concerned with putting you through a constant churn of new players rather than letting any single social interaction linger. Or, in his words: “TF2 is where you go to meet your friends, Overwatch is a thing you do with your friends.”

It’s easy to see why. Multiplayer spaces have become impermanent, intangible. Community servers phased out in favour of matchmade strangers duking it out for a few rounds. Once you’re done, it’s back into the matchmaking pool you go. You’re playing with and against real people, but the experience is all about you—your skill, your progression. Everyone else is background noise.

Pushing back has always meant breaking the game a little. In Dota 2, we turned frustration at both teams having their ranks gutted by poor drafts into cooperation, as the remaining players banded together to take down the map’s powerful monsters. In Overwatch, a friend and I would approach foes with weapons lowered and “Hello” emotes raised.

It’s not too long before the walls close back in. Overwatch will slap you with an AFK timer should it so much as sniff any sub-optimal play coming from your end. And as much as that one round of Dota was a riot, its deadly-serious 90-minute skirmishes create staggering social pressure to be on your game from the get-go.

Whether through systems or community expectations, these spaces increasingly demand conformity.

Splatoon 2 shouldn’t be any different, really. Short rounds and small lobbies mean you’re rolling through game after game of seemingly throwaway players. It’s not even that this version of Splatoon is bad, either—in the six months I’ve owned a Switch, it’s eaten more hours than everything I own on the console combined. Thrice.

The game’s wall-painting, shape-shifting play is a masterclass in map control and momentum. Its style and sounds evoke Jet Set Radio with a seafood twist. But something about Nintendo’s ink ‘em up elevates it into a playful refuge against more throwaway online spaces.

Maybe it’s the game’s deeply playful attitude. Even compared to the equally colourful Overwatch, Splatoon is aggressively positive—utterly lacking the masculine language of power and competition. As Nintendo’s first online shooter, it isn’t trying to service 20 years of hardcore FPS players. It’s trying to be a good time.

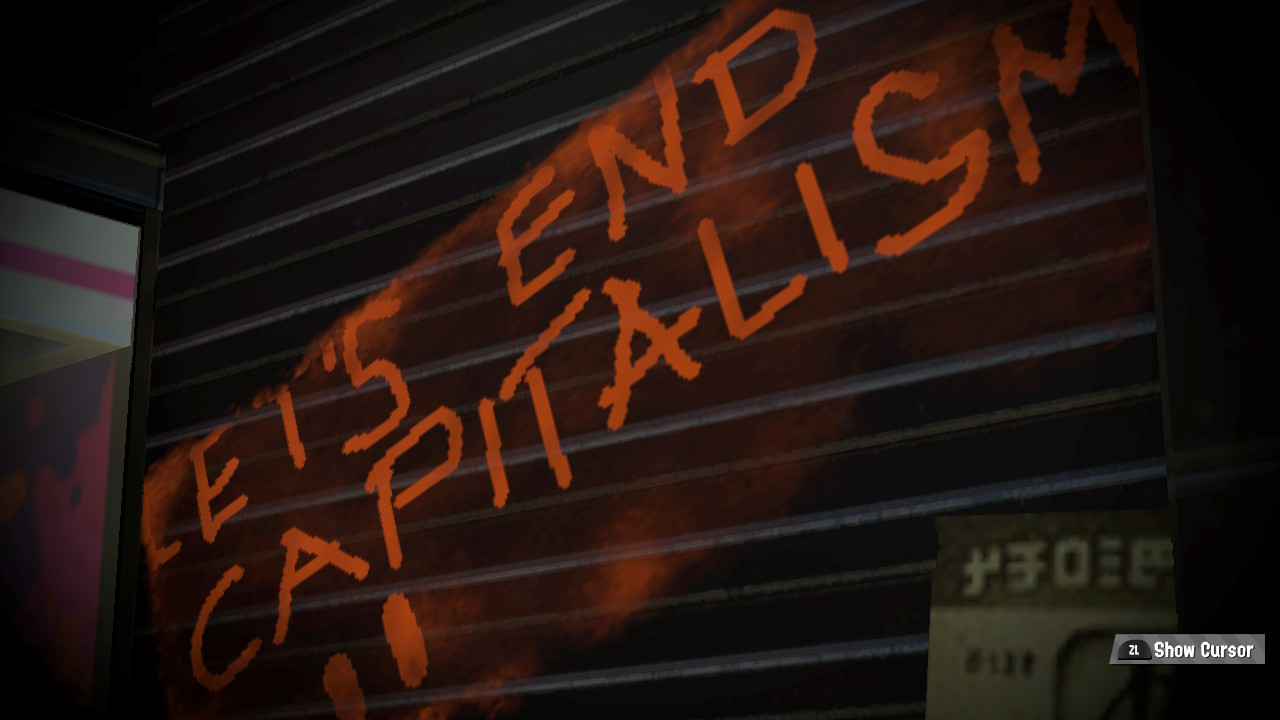

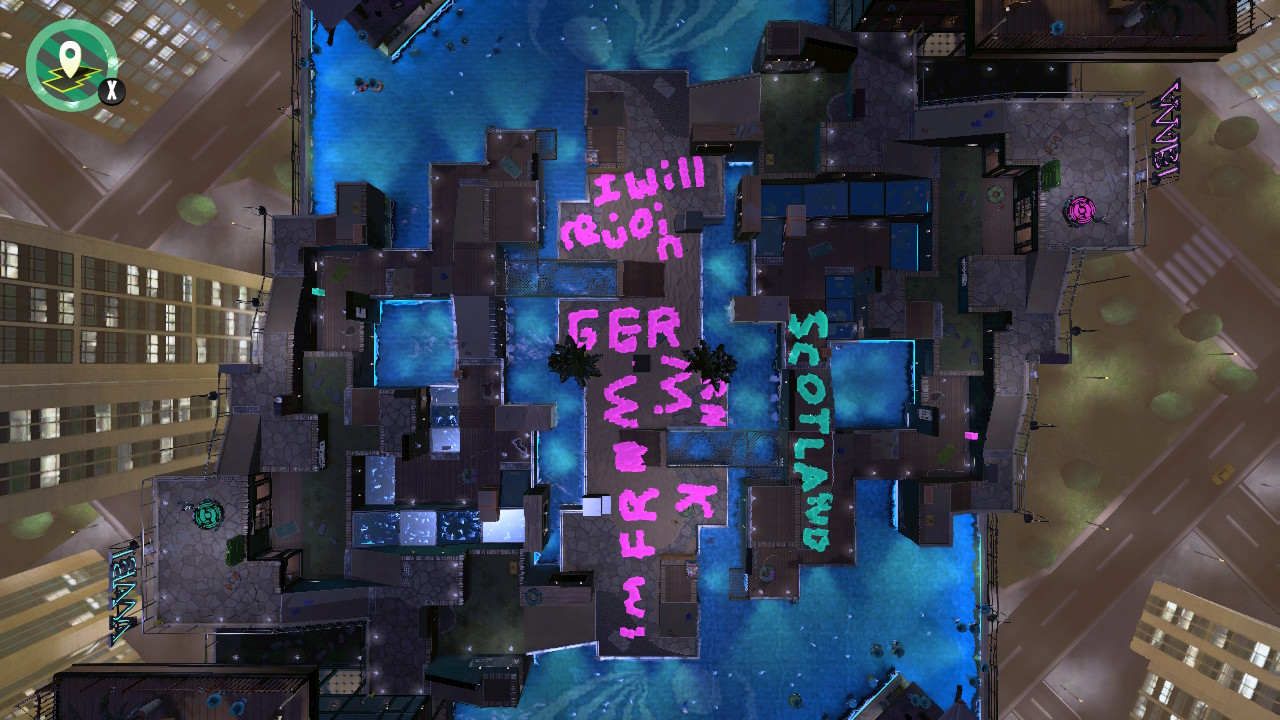

Splatoon is full of cephalopod zoomers—young, queer, and relentlessly online. This is best seen strolling through The Square, a Tokyo-styled analogue to Destiny’s Tower where likenesses of other players hang out and display simply drawn “posts” above their heads or scrawled graffiti-style on walls.

Watching post trends fall in and out of fashion is a personal obsession. Watching “Ok Boomer” ebb and flow in popularity, as a week of “Trans Rights!” gives way to genuine advice on staying safe during the Covid-19 outbreak.

Even Switch Online’s bare-bones social features can’t keep us from hanging out. Together, we’ve created our own language to communicate friendship. In Splatoon 2, you don’t say hi—you animorph twice in mid-air, and I think that’s beautiful. Sliding across the map in a slow, harmless squid form conveys passivity, while holding a throwable almost looks like you’re going in for a high-five if you squint hard enough.

It’s almost beside the point that Splatoon’s core mechanic is painting on the ground. Chargers become ballpoint-pens, ideal for inking out short messages. Broad-tipped Octobrushes can lay down a love heart in a single stroke. I’ve seen some squids show a staggering efficiency in inking their Snapchat or Instagram handles within the tight confines of Splatoon’s limited map geometry—the only reliable way of taking that relationship beyond the game.

They’re creative expressions in themselves, right at home in a game where dressing up slick and drawing killer posts is just as important as your aim. A community that’s willing to take Nintendo’s limited toolset and run wild with it.

Some of these familiar strangers have made their way to my Animal Crossing: New Horizons home. Here, we can finally talk freely and get to know one another, in a space that’s only ever been concerned with good times with good friends. But they’re times I wouldn’t have to begin with, if we hadn’t all been bringing that attitude to Splatoon’s battlefields ahead of time.

It’s that simple willingness to put down our weapons and just enjoy each other’s company that keeps me coming back. I’d largely come to peace with the way things had gone—for all my mourning regarding dedicated spaces they came with some serious baggage of their own, wracked with infighting, gossip and strange, intangible hierarchies. For a long time, I reckoned that my need for regular online spaces was well behind me.

But against the backdrop of a global pandemic, these impromptu parties have become essential. As I write, my country has finally (belatedly) entered lockdown. With even my sparse social life put on hold for the foreseeable, I don’t want to spend my time online in fierce competition. I just want the playground to be open again.

from VICE https://ift.tt/39sIAE0

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment