This spring, VICE partnered with Fotografiska New York to present New Visions, an exhibition showcasing 14 emerging photographers from around the world who are changing the way we see. To highlight the work beyond the museum, we asked 14 of our favorite, fresh voices in culture to respond to the photos in writing. Here, writer and curator Kimberly Drew engages photographer Texas Isaiah about his work. Read more from the New Visions series here, and learn how to visit the show at Fotografiska New York here.

Texas Isaiah first asked me to sit for him in 2014, almost a year after we had first met. When I arrived at his Crown Heights apartment to shoot for his series Blackness, I was anxious and unsure of what to expect. I wore a short black dress that I had “borrowed” from my aunt because it made me feel like an adult. As I waited for Texas Isaiah to reach the door, I tried to relax my body in anticipation of our shoot. I wanted to be professional and poised. I’d seen his other images where his subjects seemed so fully realized—imbued with joy, pointed curiosity, and ease. I wanted my portrait to have that energy, too.

Moments later, as I sat in front of Texas Isaiah’s lens, I quickly learned that this wouldn’t be like other photoshoots. I couldn’t force the levity that I saw in his photos. Instead, we chatted and took our time. He offered me water and tea. It seemed like the whole afternoon was ours for the taking. The images would come. By the end of our hour-long session, it came naturally, and I walked away with much more than a portrait. It was in that moment of vulnerability that I first got to be a recipient of Texas Isaiah’s care as an artist.

Today, as the coronavirus hits the arts in unprecedented ways, we find ourselves in a communal panic. How will future audiences interact with artworks? Will museums weather this crisis? Curators, educators, and artists alike are scrambling to find some sense of normalcy as things shift. In this moment of tenderness, it’s vital that we think about how to extend kindness and compassion as we witness and hold space for each other. It’s urgent that we find new strategies for connecting within our industry and with the world around us.

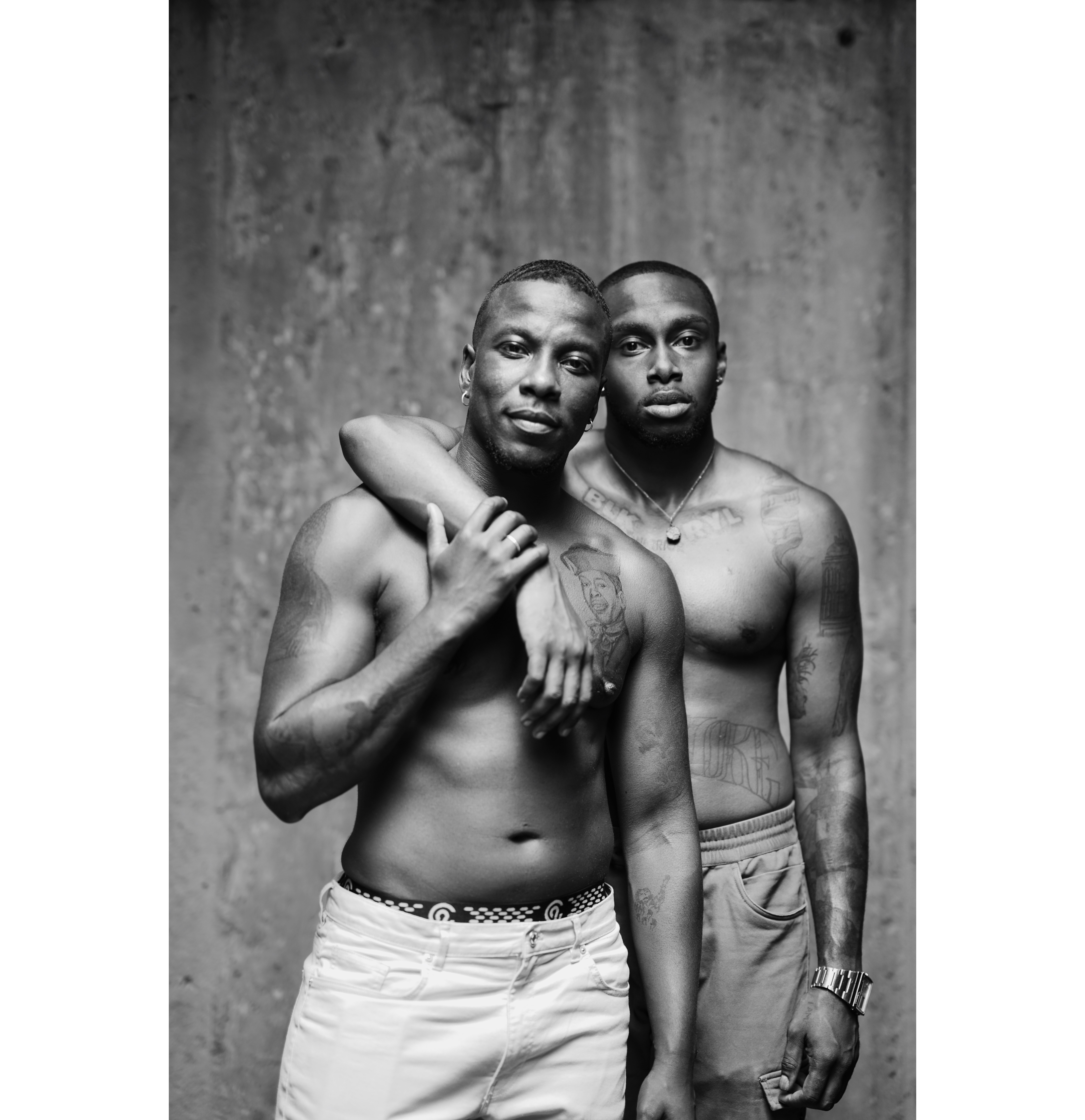

Texas Isaiah’s practice, built on a foundation of care-taking and mutual respect, is a helpful blueprint for what a more thoughtful, more compassionate art world could look like. In his projects Blackness, Every Image is an Offering, and Flowers at Your Feet, he aims to complicate traditional modes of representation by emboldening his sitters and resisting set expectations. Recently, I spoke to the artist to discuss these projects, his thoughts on portraiture, and his hopes for the future.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

KIMBERLY DREW: How are you, where are you, and how are you holding up in this moment of extreme uncertainty?

TEXAS ISAIAH: I am doing a little better now that I've created a routine for myself. I am now in Los Angeles between Hollywood and Mid-City. I often prioritize rest and care for myself, so the adjustment wasn't as significant, but my worry and frustrations have been centered around my health and the wellbeing of others. So, I'm grateful that I'm finding ways to keep myself occupied that exist outside of this sense of productivity surrounding my work. I've been doing puzzles. I've purchased coloring books and crayons and things that I feel like my inner child needs during this moment.

Could you talk to me about why you became an image maker? I wonder if you could talk a bit about why photography is important as an act.

I became an image maker by chance. I'm the first known artist in my family. I was in the middle of figuring out what contributions I wanted to put into the world, and I stumbled onto image making, and through the ups and downs, I fell in love. I feel like that had a lot to do with the movement I was participating in as an artist. When I say that, my first experience outside of an academic space involving photography was music. I was a part of a band. I toured. I was a tour photographer and then I went on to nightlife and documented young, Black people curating events in Soho and Brooklyn and all over Manhattan. Then went into live performance photography and then went into portraiture.

I'm very interested in filmmaking and creative direction and I feel like I would venture more into those interests. However, I still feel like I have more ground to cover when it comes to producing still images. I think that documentation plays a massive role in archiving our day to day lives.

For Every Image is an Offering, which you recently launched with VSCO, Jess Arendt poses the question, "What if representation isn't about a finished product, but process?" Could you talk a little bit about your process as a visual narrator? How has it changed over time? Does it change in the moment while you’re creating?

Yes, it does change in the moment that I am creating an image with another individual, and I often leave space for that to happen. I don't have expectations that this session is going to go well. I just come into it knowing that whatever happens, happens, and if it doesn't go as well as we both would have liked it to, we can always return. So it's also allowing an individual and I to meet up again in the future and figure out, "Okay, how can we make this right and also how can we keep this process going?"

The first question I ask a sitter, especially if it's the first time we were working together, is whether or not they have a relationship with image making and if they feel anxious about being photographed. I typically allow a sitter to choose a location, and if they're unable to, we select a space together.

I feel like my process took a turn in 2013 as I was producing my first solo project, Blackness. Blackness is a portrait series that documents and celebrates the diversity of the African diaspora across spectrums of gender, sexuality, and ethnic heritage. During the time of developing a project, I had 12 people pass away, and I was in the middle of processing that loss. It was also the beginning of the first wave of the “trans tipping point,” and I was questioning my participation in those discussions. I think it taught me the importance of taking my time with the production of my work, and I also needed care in relation to the grief that I was feeling, but I wasn't specific on what receiving it would look like. So, my intuition was to pour comfort into my practice. I was creating a majority of my work in my home space. So, my interest in domestic environments and intentionality, mobility, and consent emerged during this time.

The portrait you took of me in 2015 is one of the most important photographs I have ever had taken of me. It taught me so much about care and consent in profound ways. In an article for Artforum, our dear friend Tiona wrote, "Texas Isaiah feels you as much as he sees you." There are so many ways in which portraiture as a medium has been historically extractive. I wonder how you manage to keep feelings as a priority in your work.

I feel that my ability to manage emotions and feelings in my work comes from being a sensitive and attentive man. It's how I live my life, so of course it will show up in my work and my interactions. It is something that I feel the pressure to turn off, but I know that the world needs more of it, so although some shame and guilt may arise, it's an essential part of creating my work and being a better person. Sometimes I feel like I don't have the space to discuss how exhausted I typically feel because I am masculine.

So I do feel like sometimes I am overcompensating, but also a part of me is just, this is how I am. My mother has been very nurturing to me and so has my father in very particular ways. And so it certainly dives into the spirituality that I hold within my work and within my private, personal life.

We recently celebrated Trans Day of Visibility, a day that carries a lot of weight for transgender and gender-expansive folks. I wonder if you could talk about the role that you feel you play in telling the stories and making visible transgender and gender-expansive people, and your hopes, if any, for the future of visibility.

I think, in the beginning of my own journey, I definitely witnessed a lack of images of Black trans and gender-expansive people. Currently, there are more images in mainstream media, however, I find that the majority of images are being taken by white, cis-heterosexual men. I feel like it is my duty to share these stories of trans and gender expansive people and also put them to the forefront of the work. So I'm not telling their story, I'm acting as a conduit, as a vessel for them to tell their own stories, because they haven't been [able to] for a very long time. Because these folks have their own autonomy, and I don't want to take that away when I am discussing the work that I am creating with them.

I think one of the things that does frustrate me is the lack of intention that we have when we're curating language around what Black image making can look like. I do see a lot of people speaking about maybe their own work or a particular kind of work and coining it as, like, work for all Black people. I don't say that because I know that there are a lot of voices missing from my work. There is more that I can do. I can't satisfy every Black person in the world. But I can try my best to connect with different individuals for them to tell their stories.

Visibility is very complicated, because I feel like people have often been left out of the conversation when we do discuss representation. And so my hope for a future of visibility is for not only individuals being a part of images and moving images, but for them to take care of themselves, for them to have access to basic resources like health care, financial access to eat every day, and pay their rent on time, to support themselves, and their endeavors, whatever that would look like. That's what I would love for the future of visibility to focus on.

On the note of visibility and finding new language, could you talk about Flowers at Your Feet and who do you hope might be the audience for the series?

The idea of Flowers came about in 2017 and came into fruition within the last year. I was living in a communal household called The Altar. It was where 22 year old Ki’tay Davidson had passed away. During my two years of living in that space, I was spiritually responding to him through my work. I had not heard of him prior to [moving into The Altar] and I was beginning to meet people who knew him, people here in California. And then also, when I would travel, people would come up to me and ask me if I was living in the Altar House because they knew Ki’tay, and so I felt very connected to him in that way.

It was also around the time that I started building my altars. Flowers came out of the urgency of wanting more voices involved in the exchanges surrounding masculinity and manhood. I became more frustrated because I had witnessed, and still continue to witness, a lot of exchanges and [was] not seeing any presence of trans masculine and non-binary masculine individuals [in them]. And so at first, I had proposed a project to Art Matters, and it looked very different during that time. And [later] when I was experiencing post-surgical complications, I was able to settle down and [ask myself], “What do I want to see more of? And, how can I involve myself in this work as well, instead of just being behind the camera and being a ghost?”

Because, I also am scared of being photographed. I am scared of being witnessed and seen, although that is something that I prioritize in my work. It's a way for me to overcome those insecurities and the desire to be invisible. I started shooting it in August of last year, and it’s a project that is still... there's no end to it. I like my projects to be very open, so in terms of who I hope to see Flowers, I want everyone to see Flowers. Yes, it does prioritize trans masculine and non-binary masculine individuals, but I don't want people to box the work in. The reason why it took me such a long time to produce this work is because I automatically know where people are going to place this work.

It may be something that is celebrated during one month and then people forget about it. And I don't want that for myself and for these individuals who have showed up for their own images. And so I hope everyone will see it. I hope everyone will learn from it, because at the end of the day, the reason why I'm creating this project and thinking about producing events and workshops and hiring some these individuals who are being photographed for this project is because I want to be a part of a conversation that creates a better world for people who have experienced the violences that come with patriarchy. I want the world to be better for women and femme folks, and I think that we can move a little bit more forward than we have by inviting more men of different experiences to the table.

There's something that you said in your last answer that stuck with me: We’ve talked a lot about your work over the years, but I had no idea you were afraid of being photographed.

I think it was something that came about during the time that I started Blackness. I found myself taking self portraits for that project and developing a series that was more around my medical transition. It was a project that I stopped because I felt like it was not going into a productive direction. But, what's very interesting about those black and white images I created was that I was presenting myself as a silhouette, as a spirit. I think part of that was to redirect a conversation around images of trans bodies during that time, but it was also a way for me to hide. Hide and also feel comfort by being in the shadows. I think, like everyone else, I look in the mirror and there are always things that I can find to be judgmental about. And, I think it has increased even more, because within my personal experience, I do feel some pressure to be more cis-assumed—and knowing that I don't have control over that because, like everyone else, I want to feel desired and I want to feel loved, and I want to feel beautiful, and I want people to tell me that I'm beautiful.

I think when it comes to being photographed and how my images have played out, like I said, a part of it deals with me hiding, but it's also a part of it when the work does go out into the public and I do think about the audience. I don't want the audience to look at images of me and try to box me in. I think a part of me staying away from the camera is to interrogate that a little bit and to also just play with people. I feel like I'm a little playful and I like for people to think more about the images that they're witnessing.

And so I think moving forward, especially with Flowers, there are going to be more images of me at the forefront, looking at the camera and engaging with the audiences. And I just felt like it just took me a little bit more time to not only feel comfortable with myself, but to also figure out what I need from photography. And I feel like if I didn't take the time to ask myself those questions, I wouldn't be able to engage with individuals on that same note. It's like I can't tell people the work that they need to do without doing that work myself.

Okay, last question, and this is more just a fun one. If you could give a prompt to photographers or visual narrators who are making work during quarantine, what would you challenge them to do?

I would challenge them to turn the camera onto themselves. I would love to see more self portrait projects, if photographers are not already doing that. I feel like... I can't... I know people have roommates and they have significant others, but some people may just be going through this by themselves, and I think it would be very interesting to see images of that person on a day to day basis, not even for the public, but just for themselves.

from VICE https://ift.tt/3cTA8Qc

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment