Joe Manchin III, the Democratic senator from West Virginia, isn’t in an enviable position. In 2016, President Trump won by a 42-point margin in his state, which currently has a Republican governor, a Republican senator, a Republican-controlled legislature, and a fully Republican delegation to the House of Representatives. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Senator Munchin skews conservative, voting in line with President Trump’s position about half of the time, which has included opposing humanitarian aid at the U.S.-Mexican border, banning federal funds for abortions, and repealing guidelines to protect borrowers from predatory loans.

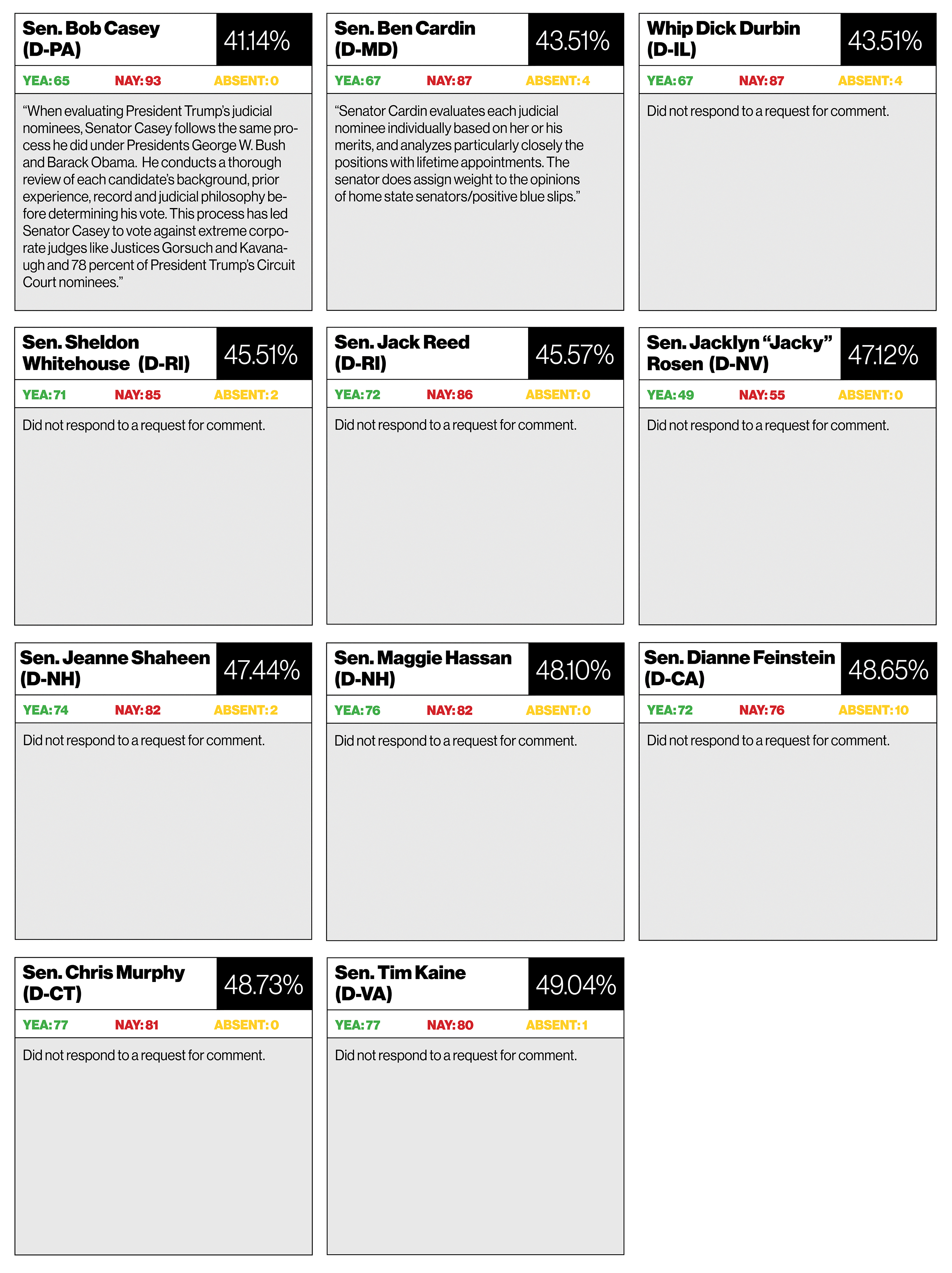

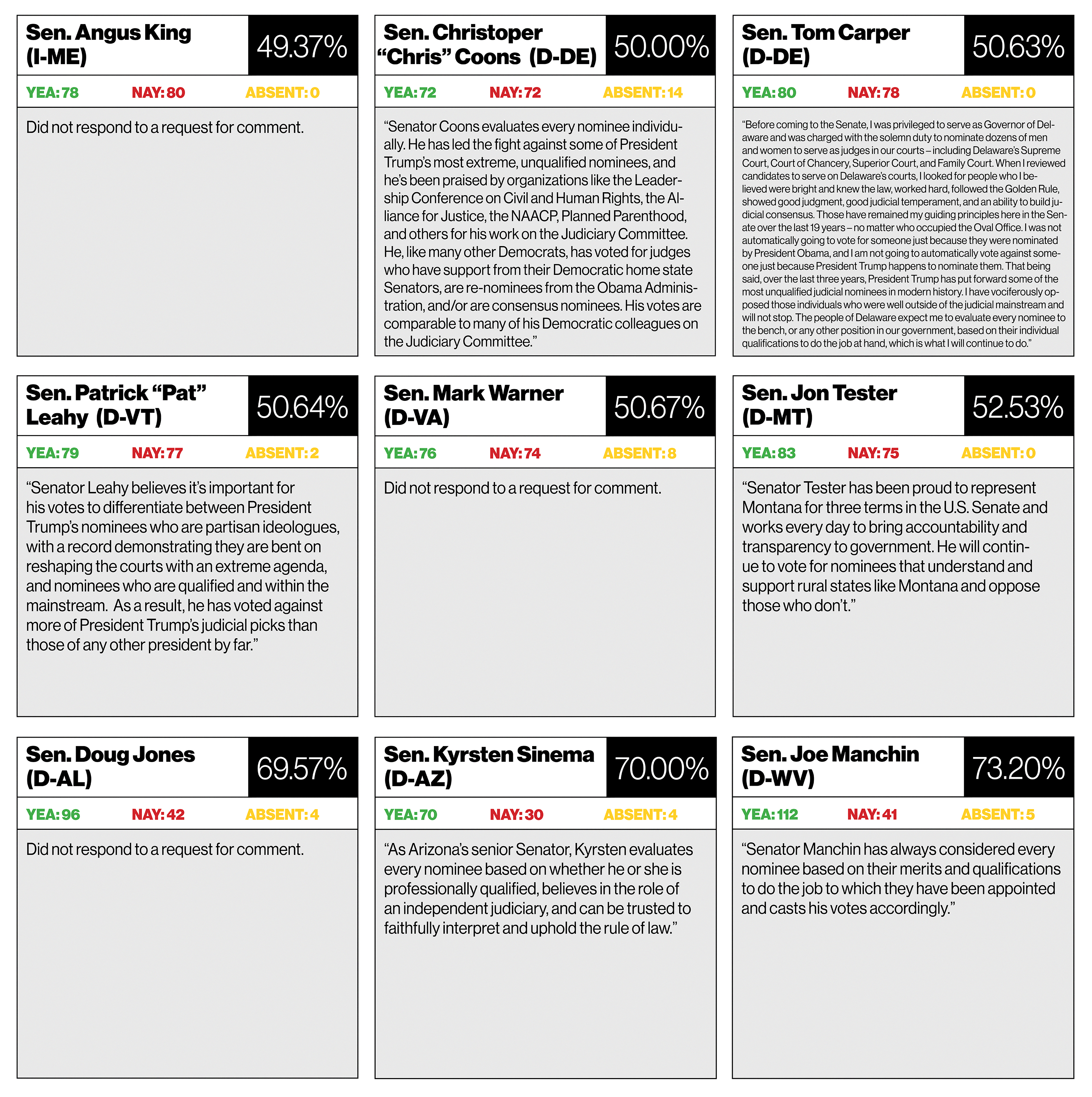

But when it comes to Trump’s judicial nominees, Senator Manchin is especially eager to align himself with the president, voting to confirm them 73 percent of the time. Compared to his Democratic colleagues, Manchin is an outlier, but he’s by no means an aberration. In fact, on average, Democrats vote to confirm Trump’s nominees roughly 39 percent of the time; even Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, who ran their races for president by arguing they were each the respective progressive futures of America, vote to confirm approximately one out of every ten of Trump’s nominees.

The data, provided by Quorum, a public affairs software company, and analyzed by VICE, omits voice votes, votes on whether to end debate on a nominee (called “invoking cloture”), and votes on the 14 justices who were nominated by President Obama (but not confirmed) and then re-nominated by President Trump. It includes all of Trump's district, circuit, and Supreme Court nominees, starting with the first—Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, nominated just 12 days after Trump’s inauguration—and continues to the present day, as the Senate is back from its recess and likely to restart the confirmation process this week.

On the Senate’s agenda is filling the 76 current vacancies on the District and Circuit Courts, which will add to President Trump’s robust and hotly discussed judicial legacy. Currently, 193 of his judges sit on the bench, accounting for a fifth of the federal judiciary. A majority of the circuit courts now have more jurists nominated by Republicans than Democrats.

Since the beginning of the Trump presidency, packing the courts has been the very open secret of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, whose personal motto is, “Leave no vacancy behind.” Toward that end, Republicans have sought a specific type of nominee. Besides being reliably conservative, predominantly men, and almost exclusively white and straight, they’re also quite young by the standards of the position.

Appointed for life, these nominees will likely serve for decades before retiring (in the 231-year history of the federal judiciary, only eight judges have been impeached and removed from office), and, especially at the circuit court level, their decisions will almost certainly not be overturned by the Supreme Court, which hears about 1 percent of the cases that are submitted for its review.

In the minority, some Democrats believe they have no way to slow this onslaught. Says Senator Brian Schatz of Hawaii: “If we want to stop these unqualified—and very youthful— ideologues from being given lifetime appointments to the federal bench, we just have to take the Senate.” But with the stakes so high and the ramifications so indelible, why have Democrats been so willing to confirm Trump’s nominees?

The Nominees

Several of these judges have made the news—most notably, Brett Kavanaugh, for the allegations of sexual assault against him, but also those who the American Bar Association rated as “not qualified.” No district or circuit court nominee from the past six presidents earned such a designation. So far, nine of Trump’s have, including Lawrence VanDyke, who the ABA’s report said was “arrogant, lazy, an ideologue, and lacking in knowledge of the day-today practice including procedural rules,” and Sarah Pitlyk, who “has never tried a case as lead or co-counsel. . . never examined a witness. . . [never] taken a deposition. . . argued any motion in a state or federal trial court. . . picked a jury. . .[or] participated at any stage of a criminal matter.”

These “not qualified” nominees account for less than one percent of Trump’s nominees, but it’s important to remember that these ratings assess only a candidate’s fitness for office, not the quality of their jurisprudence. “This a misconception that some people have,” says William Hubbard, the former president of the ABA, “that the ABA promotes or makes nominations or recommendations for these judgeships. We absolutely do not.” Instead, the group interviews the nominee’s peers, coworkers, and colleagues and condenses their sentiments into a single report.

As a result, even judges who weren’t deemed “not qualified” may have opinions far from the mainstream. For example, Neomi Rao received a majority “well qualified” ranking from the ABA, the highest designation. Then, she was confirmed to the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, and last October, she ruled that the House of Representatives had no right to see President Trump’s tax returns. “Investigations of impeachable offenses simply are not, and never have been, within Congress’s legislative power,” she wrote in her minority dissent.

Several legal scholars disagreed with Rao. “The dissent proposes a brand-new test for the President,” her two colleagues on the D.C. Circuit wrote in their majority opinion. “Congress must either initiate the grave and weighty process of impeachment or forgo any investigation in support of legislation.” Neal Katyal, the former Solicitor General, was more blunt in his commentary: “This is nuts+profoundly antidemocratic,” he wrote on Twitter.

The History

Judgeships weren’t always so polarizing. According to Andre Davis, an Obama appointee and a former justice on the Fourth Circuit, judicial confirmations were largely routine affairs until President Reagen nominated Robert Bork. “The progressives really went after him in ways that they had rarely gone after a nominee of a Republican president,” says Davis. “So it really became quite a spectacle.” One hundred and eight days after Reagan nominated Bork, the longest wait of any nominee in recent history, the Senate rejected him, with two Democrats voting in favor and six Republicans voting against.

Four years later, the Senate considered Clarence Thomas, who, at his confirmation hearing, was accused of sexual assault by Anita Hill. Though the Democrats controlled the Senate at the time, 11 members of the party voted to confirm Thomas, elevating him to the Supreme Court by the narrowest margin since 1881. But by the time Davis was nominated for the judiciary—in 1994 by Bill Clinton—the process had lost some of its partisan rancor.

“It was quite civil and civilized,” says Davis. “Clinton nominated a large number of African-Americans, such as myself, and a large number of women, and I think perhaps that may have had something to do with it—-the sense, generally speaking, that if he was nominating qualified people who were largely moderate, that [there would be] a relative quiet around nominations. Which is not to say that there weren’t some big fights, but I have to say I was treated very fairly by the Republicans.”

The Procedure

In terms of procedure, though, Davis’ nomination bears little resemblance to what has happened under Trump. In March of 2016, the final year of his presidency, Obama nominated Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court. Foreshadowing the tactics he would use later, Mitch McConnell argued that the Senate shouldn’t consider Garland because it was an election year, in accordance with an unwritten, inconsistently followed precedent called the “Thurmond Rule.”

“Strictly speaking, I don't think anybody before 2016 actually believed the Thurmond Rule applied as early as [March], and certainly not for a Supreme Court vacancy,” says Davis. Regardless, Garland wasn’t considered, Trump won the presidency, and his nominee Neil Gorsuch was confirmed to the Supreme Court. From there, the procedural changes kept rolling.

Traditionally, when making judicial nominations, the White House has asked for recommendations from the senators of the nominee’s home state. At the very least, if these senators didn’t support the nomination, it wouldn’t move forward. That courtesy, and many others, disappeared under Trump, as best told by Senator Maria Cantwell, who spoke on the Senate floor against the nomination of Eric Miller, a circuit court judge both she and her colleague from Washington opposed.

“Since 1936, only eight judges have been confirmed when one home state senator objected, and in every case, confirmed nominees have been supported by at least one senator from their nominee’s home state,” she said in February of last year. “[Miller’s] confirmation hearing was held during a recess last Congress, when the vast majority of senators were back in their states. In fact, only two members of the United States Senate were present at the hearing, and neither one of them were Democrats. Mr. Miller was questioned for less than five minutes, and when the Judiciary Committee Democrats requested another hearing, that request was rejected.”

According to Maggie Jo Buchanan, the director of legal process at the Center for American Progress, Eric Miller’s confirmation was “a sign of things to come.” She points to the extension of a rule change that was originally initiated by Democratic Senator Harry Reid, the former Majority Leader. In 2013, Reid invoked the so-called “nuclear option” by lowering the necessary vote threshold from 60 to 51 for nominees of all judgeships except the Supreme Court. In 2017, Senator McConnell eliminated that exception.

“Neither of Trump’s Supreme Court justices would have met the 60-vote threshold of the past, and they are the only one of their colleagues with that distinction on the Supreme Court right now,” says Buchanan. In fact, 40 percent of Trump’s judges have passed with fewer than 60 votes, though the president has shown no compunction about failed nominations. Of the last six presidents, the average confirmation success rate was 86 percent. In his first two years in office, Trump’s was 54 percent. Still, he’s outpaced every other president in terms of how quickly he’s filled court vacancies.

The Democratic Response

Comparisons between senators' records on Trump's nominees aren’t perfect. Sanders and Warren, along with three other senators who were campaigning for the presidential nomination (Kamala Harris, Amy Klobuchar, and Cory Booker), were absent for at least a third of the votes considered. In fact, Senator Booker has missed nearly half (77 of 158), while 15 of his colleagues have never missed even one. In addition, four Democrats (Doug Jones, Kyrsten Sinema, Tina Smith, and Jacky Rosen) began their terms after Trump took office, so they’ve considered fewer nominations. As a result, in determining how often they voted for a Trump nominee, VICE calculated each senators yes / no percentage for only the votes they were present for.

The more fundamental question, however, is this: Why are Democrats voting for any of these nominees, who will likely be the most indelible mark that Trump leaves on the country? Especially now, when partisanship is so severe that blue-state senators could easily campaign and fundraise on a platform of never once supporting the Trump judiciary, why does the party say “yea” nearly 40 percent of the time?

To find out, VICE also contacted the offices of every Democratic and Independent senator and asked for their criteria for evaluating judicial nominees. Of the 47, 20 responded, though even when pressed for specifics, many were vague, like this one: “Senator Manchin has always considered every nominee based on their merits and qualifications to do the job to which they have been appointed and casts his votes accordingly."

But others pointed out that the dynamics are more complicated than the yes / no votes suggest. Because Republicans can withdraw a nomination if they believe the judge doesn’t have enough support (which has happened 13 times during Trump’s term), her confirmation is practically inevitable once she reaches a full floor vote in the Senate (no Trump nominee has ever lost a vote at that stage). For that reason, Democrats have two options. First, they can derail the nomination earlier in the process. For example, after the cloture vote, the two senators from Oregon, both Democrats, successfully campaigned against a 9th Circuit nominee who “failed to disclose inflammatory writings that reveal archaic and alarming views about sexual assault, the rights of workers, people of color, and the LGBTQ community.”

Democrats can also recommend their own nominees. Even with Senator McConnell’s disregard for the blue-slip system, there has been space for bipartisan cooperation. For example, before joining the Senate, Tom Carper was the governor of Delaware, whose constitution used to require political balance among its judges. In that spirit, he and his co-senator from the state, Chris Coons, worked to have nominated two district court judges under Trump, both of whom were confirmed with voice votes.

So, while many of Trump’s nominees are conservative ideologues, not all are, an idea best summed up by Senator Chuck Schumer of New York: “I voted against the overwhelming majority of President Trump’s judicial nominees because they lack the necessary experience and hold radical ideologies that make them unfit for a lifetime judicial appointment. In the instances I voted in favor of President Trump’s nominees, many of whom were recommended by Democratic Senators, I did so after thoroughly reviewing their records and determining that they were fit for lifetime appointments to the bench.”

Without a majority and subject to procedural changes that minimize their influence, Democrats have limited options to resist Trump’s judicial agenda. They can target the least qualified, most extreme candidates and hope that public pressure will result in a withdrawn nomination. They can recommend justices who are moderate enough to win the favor of the president and Senator McConnell. And they can cross their fingers that at least some of the newly-seated justices have a change of heart.

Consider Hugo Black, a senator from Alabama who was nominated for the Supreme Court by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1937 and who had once been a member of the Ku Klux Klan. “As you can easily imagine, liberals, progressives, many constituencies went after him pretty ferociously,” says Davis, the Obama appointee. “But in the end, he became one of the most liberal justices on the Supreme Court.”

Though Black’s legacy is slightly more complicated (he both wrote the majority opinion authorizing the internment of Japanese citizens during World War II and supported desegregation in Brown v Board of Education), he offers a prescient lesson: that over the course of a lifetime appointment, a justice’s viewpoint may change. But if you want to hedge your bets, it’s best to control the Senate.

With help from Kris Kelkar on data analysis.

Follow Spenser Mestel on Twitter.

from VICE https://ift.tt/3faD5Oe

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment