For years, a California man systematically harassed and terrorized young girls using chat apps, email, and Facebook. He extorted them for their nude pictures and videos, and threatened to kill and rape them. He also sent graphic and specific threats to carry out mass shootings and bombings at the girls' schools if they didn't send him sexually explicit photos and videos.

Buster Hernandez, who was known as “Brian Kil” online, was such a persistent threat and was so adept at hiding his real identity that Facebook took the unprecedented step of helping the FBI hack him to gather evidence that led to his arrest and conviction, Motherboard has learned. Facebook worked with a third-party company to develop the exploit and did not directly hand the exploit to the FBI; it is unclear whether the FBI even knew that Facebook was involved in developing the exploit. According to sources within the company, this is the first and only time Facebook has ever helped law enforcement hack a target.

This previously unreported case of collaboration between a Silicon Valley tech giant and the FBI highlights the technical capabilities of Facebook, a third-party hacking firm it worked with, and law enforcement, and raises difficult ethical questions about when—if ever—it is appropriate for private companies to assist in the hacking of their users. The FBI and Facebook used a so-called zero-day exploit in the privacy-focused operating system Tails, which automatically routes all of a user's internet traffic through the Tor anonymity network, to unmask Hernandez's real IP address, which ultimately led to his arrest.

A Facebook spokesperson confirmed to Motherboard that it worked with "security experts" to help the FBI hack Hernandez.

“The only acceptable outcome to us was Buster Hernandez facing accountability for his abuse of young girls,” a Facebook spokesperson said. “This was a unique case, because he was using such sophisticated methods to hide his identity, that we took the extraordinary steps of working with security experts to help the FBI bring him to justice.”

“Since there were no other privacy risks, and the human impact was so large, I don’t feel like we had another choice.”

Former employees at Facebook who are familiar with the situation told Motherboard that Hernandez's actions were so extreme that the company believed it had been backed into a corner and had to act.

“In this case, there was absolutely no risk to users other than this one person for which there was much more than probable cause. We never would have made a change that affected anybody else, like an encryption backdoor,” said a former Facebook employee with knowledge of the case. “Since there were no other privacy risks, and the human impact was so large, I don’t feel like we had another choice.”

According to several current and former Facebook employees that Motherboard spoke to, however, the decision was much more controversial within the company. Motherboard granted several sources in this story anonymity to allow them to discuss sensitive events protected by non-disclosure agreements.

The crimes Buster Hernandez committed were heinous. The FBI's indictment is a nauseating read. He messaged underage girls on Facebook and said something like “Hi, I have to ask you something. Kinda important. How many guys have you sent dirty pics to cause I have some of you?,” according to court records.

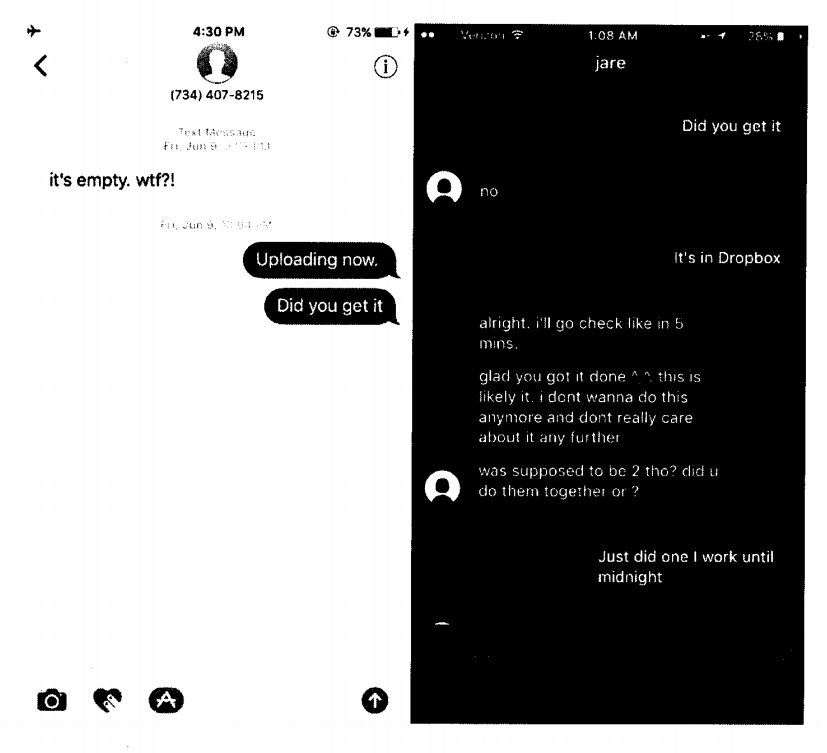

When a victim responded, he would then demand that she send sexually explicit videos and photos of herself, otherwise he would send the nude photos he already had to her friends and family (in reality, he didn’t have any nude photos). Then, and in some cases over the course of months or years, he would continue to terrorize his victims by threatening to make the photos and videos public. He would send victims long and graphic rape threats. He sent specific threats to attack and kill victims’ families, as well as shoot up or bomb their schools if they didn’t continue to send sexually explicit images and videos. In some cases, he told victims that if they killed themselves, he would post their nude photos on memorial pages for them.

He told victims he “wants to be the worst cyberterrorist who ever lived.”

“I want to leave a trail of death and fire [at your high school],” he wrote in 2015. “I will simply WALK RIGHT IN UNDETECTED TOMORROW … I will slaughter your entire class and save you for last. I will lean over you as you scream and cry and beg for mercy before I slit your fucking throat from ear to ear.”

Do you work or did you use to work at Facebook? Do you work for the FBI or develop hacking tools for law enforcement? We’d love to hear from you. You can contact Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai securely on Signal at +1 917 257 1382, OTR chat at lorenzofb@jabber.ccc.de, or email lorenzofb@vice.com

All along, he would claim he couldn’t be caught by the police: “You thought the police would find me by now, but they didn’t. they have no clue. The police are useless,” he wrote. “Everyone please pray for the FBI, they are never solving this case lmao … I’m above the law and always will be.”

Hernandez used the secure operating system Tails, which runs the anonymizing software Tor and is designed to encrypt and push all of a user's traffic through the network by default, hiding their real IP address from websites or services they use. Using this tool, he contacted and harassed dozens of victims on Facebook for years until 2017, according to court documents. The operating system is also widely used by journalists, activists, and dissidents who are under threat of being surveilled by police and governments. A spokesperson for Tails says it is “used daily by more than 30,000 activists, journalists, domestic-violence survivors, and privacy-concerned citizens.”

Hernandez was so notorious within Facebook that employees considered him the worst criminal to ever use the platform, two former employees told Motherboard. According to these sources, Facebook assigned a dedicated employee to track him for around two years and developed a new machine learning system designed to detect users creating new accounts and reaching out to kids in an attempt to exploit them. That system was able to detect Hernandez and tie different pseudonymous accounts and their respective victims to him, two former Facebook employees said.

Several FBI field offices were involved in the hunt, and the FBI made a first attempt to hack and deanonymize him, but failed, as the hacking tool they used was not tailored for Tails. Hernandez noticed the attempted hack and taunted the FBI about it, according to the two former employees.

“Everything we did was perfectly legal, but we’re not law enforcement.”

Facebook’s security team, then headed by Alex Stamos, realized they had to do more, and concluded that the FBI needed their help to unmask Brian Kil. Facebook hired a cybersecurity consulting firm to develop a hacking tool, which cost six figures. Our sources described the tool as a zero-day exploit, which refers to a vulnerability in software that is unknown to the software developers. The firm worked with a Facebook engineer and wrote a program that would attach an exploit taking advantage of a flaw in Tails’ video player to reveal the real IP address of the person viewing the video. Finally, Facebook gave it to an intermediary who handed the tool to the feds, according to three current and former employees who have knowledge of the events.

Facebook told Motherboard that it does not specialize in developing hacking exploits and did not want to set the expectation with law enforcement that this is something it would do regularly. Facebook says that it identified the approach that would be used but did not develop the specific exploit, and only pursued the hacking option after exhausting all other options.

The FBI then got a warrant and the help of a victim who sent a booby-trapped video to Hernandez, as Motherboard previously reported. In February of this year, the man pleaded guilty to 41 charges, including production of child pornography, coercion and enticement of a minor, and threats to kill, kidnap and injure. He is now awaiting sentencing, and will likely spend years in prison.

An FBI spokesperson declined to comment for this story, saying that it’s an “ongoing matter,” and referred Motherboard to the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of Indiana, which prosecuted Hernandez.

The United States Attorney’s Office in the Southern District of Indiana did not respond to multiple emails and calls for comment.

Facebook routinely investigates suspected criminals on its platform, from run-of-the-mill cybercriminals, to stalkers, extortionists, and people engaging in child exploitation. Several teams at Menlo Park and other company offices collect user reports and proactively hunt these criminals. These teams are composed of security specialists, some of whom used to work in the government, including the FBI and the New York Police Department, according to employees’ LinkedIn profiles.

These employees are so proud of this work that they used to have a meeting room where they’d hang pictures of people who ended up being arrested, as well as newspaper clippings of cases they investigated, according to current and former Facebook employees.

According to all the sources Motherboard spoke to, however, this was the first and only time Facebook got directly involved and helped the FBI go after a suspected criminal in this way, developing a tool specifically to de-anonymize targets. For some current and former Facebook employees who did not know of the case, as well as people with knowledge of it, that was a controversial decision.

“The precedent of a private company buying a zero-day to go after a criminal,” said a source who had knowledge of the investigation and development of the exploit. “That entire concept is fucked up [...] it’s sketchy as hell.”

Another source said that “everything we did was perfectly legal, but we’re not law enforcement.”

“I would be surprised if faced with the same set of circumstances it would happen again,” he added.

A former Facebook employee who has knowledge of the investigation, however, saw partnering with the cybersecurity firm and paying for the development of an exploit as justified, given that they were going after a serial harasser of children.

“I think they totally did the right thing here. They put a lot of effort into child safety,” said the former employee, who asked to remain anonymous as he was not authorized to speak about the case. “It's hard to think of another company spending the amount of time and resources to try to limit damage caused by one evil guy.”

“The precedent of a private company buying a zero-day to go after a criminal. That entire concept is fucked up.”

That the hack occurred on Tails, not Facebook, adds a particularly thorny ethical layer to the hack. While this particular hack was intended to be used against a specific, heinous criminal, handing zero-day exploits to law enforcement comes with the risk that it will be used in other, less serious cases. The security of these products can't be compromised for some without compromising all, and so zero-day hacking tools are often closely-held secrets and sold for high sums. If they got into the wrong hands, it could be disastrous.

A spokesperson for Tails said in an email that the project’s developers “didn't know about the story of Hernandez until now and we are not aware of which vulnerability was used to deanonymize him.” The spokesperson called this "new and possibly sensitive information," and said that the exploit was never explained to the Tails development team. Many security researchers—including those who work at big companies like Google—go through a process called "coordinated disclosure" in which the researchers will inform companies that they've found a vulnerability in their software, and will give them time to fix it before releasing the details to the public.

In this case, however, that wasn't done because the FBI intended to leverage the vulnerability against an actual target.

For years, top law enforcement officials and prominent lawmakers have rung the alarm about the so-called “going dark” problem, a scenario where criminals and terrorists take advantage of strong encryption to escape arrest and prosecution. With the rise of default encryption, law enforcement and governments are more commonly hacking their targets to obtain their communications and data.

A factor that convinced Facebook’s security team that this was appropriate, sources said, was that there was an upcoming release of Tails where the vulnerable code had been removed. Effectively, this put an expiration date on the exploit, according to two sources with knowledge of the tool.

As far as the Facebook team knew, Tails developers were not aware of the flaw, despite removing the affected code. One of the former Facebook employees who worked on this project said the plan was to eventually report the zero-day flaw to Tails, but they realized there was no need to because the code was naturally patched out.

Amie Stepanovich, the executive director of the Silicon Flatirons Center at the University of Colorado Law School, said that it’s important to remember that whoever these hacking tools are used against, they leverage vulnerabilities in software that may be used against innocent people.

“A vulnerability can be used against anyone. Tails may be used by criminals, but it’s also a tool for activists, journalists, or government officials, as well as other people to protect against bad actors,” Stepanovich, a well-known privacy and security expert, told Motherboard. “This is why it’s important to have transparent processes on the discovery and response to vulnerabilities, including a default preference for reporting them to an appropriate person, organization, or company.”

According to Senator Ron Wyden, who is a close watcher of law enforcement use of hacking, this case raises questions on how the FBI handled the hacking tool purchased by Facebook.

“Did the FBI re-use it in other cases? Did it share the vulnerability with other agencies? Did it submit the zero-day for review by the inter-agency Vulnerabilities Equity Process?” Wyden said in a statement, referring to the government process that is supposed to establish whether a zero-day vulnerability should be disclosed to the developers of the software where the vulnerability is found. “It’s clear there needs to be much more sunlight on how the government uses hacking tools, and whether the rules in place provide adequate guardrails.”

The engineers and security researchers who made the call at the time, however, said there was really no choice.

“We knew it was gonna be used for bad guys,” one of the sources with direct knowledge of the case told Motherboard. “There was a bad guy doing bad things, and we wanted to take care of it.”

Subscribe to our new cybersecurity podcast, CYBER.

from VICE https://ift.tt/3cTcV02

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment