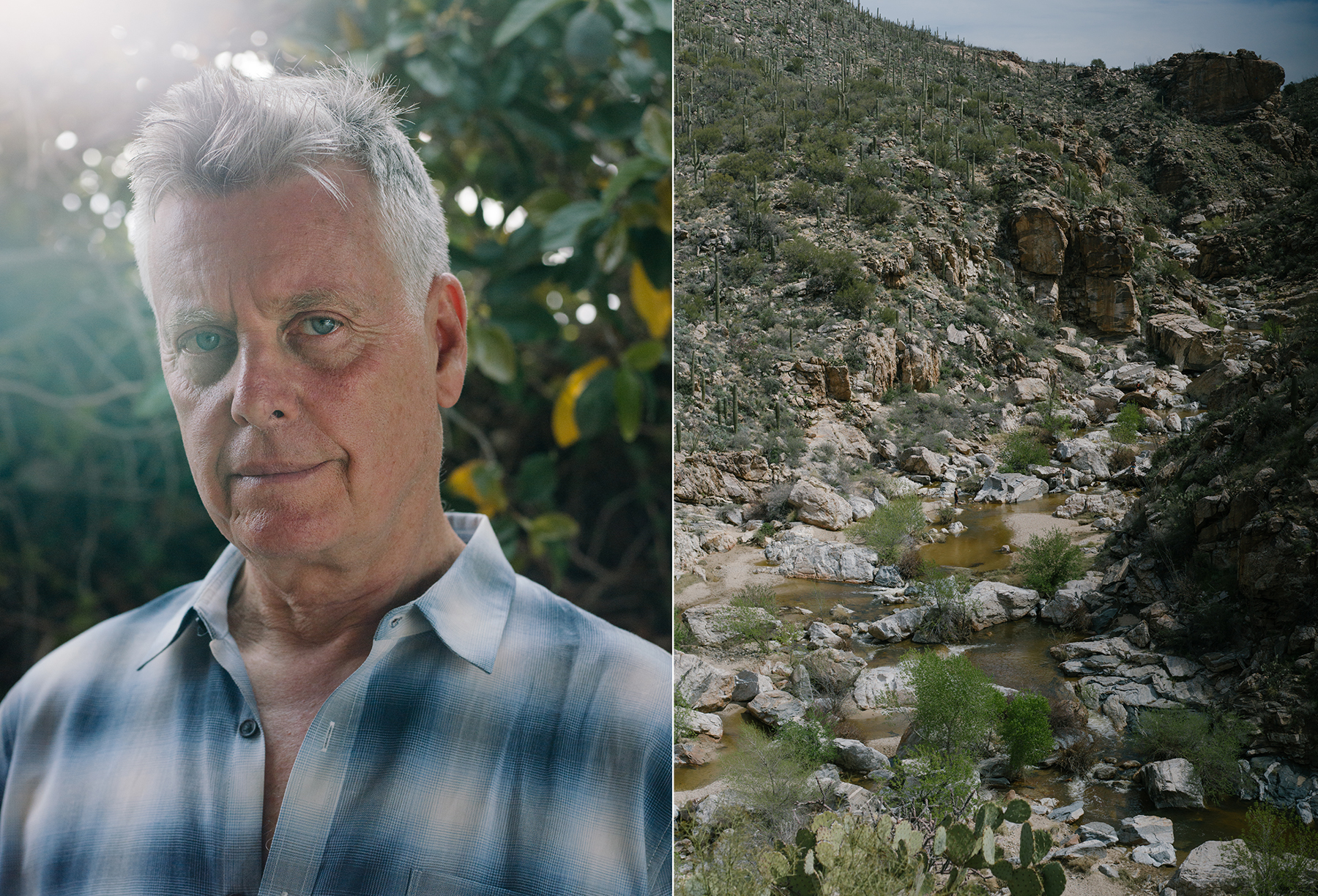

TUCSON, ARIZONA—Water flows downhill in the desert, making little white froths of spittle on the river’s surface. Over a tongue of smooth stone, it spills as orange as amber beads, and foregrounds a mountain of chameleon green saguaros bright from the winter rains. It’s here that artist and designer Chris Rush is being photographed, in advance of his first book, the heartbreaking and psychedelic memoir, The Light Years. He is 62.

Up a two days trek on foot is Helen’s Dome, which I keep looking at, like a granite fortress below a sky of aquarium blue. Chris Rush used to live up around the dome and on nearby Mica Mountain, I think, as if trying convince myself the events of his memoir are even possible. As a teenager in the early 1970s, in a tent after running away from his nouveau riche home in New Jersey to escape his father's violent, homophobic rage, and after consuming what sounds like a half a gram of LSD, Rush stayed on the mountaintop for almost two years, alone.

Standing in wet pant legs in the river, he is not like anyone I’ve met. Rush is tall and blond and barefoot, more movie star than author. He is a mix of studio artist, intellectual, spiritual guru agnostic, New Jersey Catholic queen, and the grown-up version of the experimental child he exists as in the years covered by his coming-to-enlightenment memoir. The book makes him seem otherworldly, but in it and in person, what’s more striking is that he seems to have no fear. He holds complete faith in his ability to survive, his protection by spiritual and otherworldly entities he seems to know personally; he actually seems like he may be one of the aliens whose existence he began pondering as a child. But instead of remaining an outsider, he has come out the other side hyper sane, even enlightened.

Growing up in a wealthy and glamorous New Jersey family with a father who built grand edifices for the diocese, Rush was far too smart, elegant, and sensitive for his own good, and by prepubescence had become a profound acidhead and addict too high on spiritual ideals to understand he was out of control. To add to all that, he was also a gender-defying love child who wore a pink Pucci cape at the age of ten with pride, until his father caught him. As he humorously paints it in the early pages of The Light Years:

He stopped his new Thunderbird and put down the electric window. “No fucking way! Get it off.”

“Dad, I’m Pope John—the Twenty-Third!’”

“You heard me. Get it off. Now.”

The Pucci was banned. Dad wouldn’t explain, but later, during an argument with my mother, I heard him use a new phrase.

“The boy is a goddamn queer, Norma—it’s obvious.”

“Charlie don’t say that, he just needs a challenge.”

Rush continues: “Lying on my bed, I thought: What’s a goddam queer?”

Sent away for his sexuality and gender-fluidity, Rush was unceremoniously kicked out of several boarding schools. At the first, which was also a Catholic seminary, he ordained himself as the resident acid dealer instead of the priest he’d piously thought he’d become. His older sister, Donna, turned him onto LSD at the age of 12, and introduced him to the cult-leader-esque Valentine, a sensuously beautiful psychedelic drug dealer who speaks of “Christ,” “Love,” and sacramental drugs. Rush started selling psychedelics as an underclassman after being fronted a thousand capsules of “the pink LSD” by Valentine, which he also takes almost daily and fearlessly, thinking of them as a sort of “brain vitamin.”

With Rush’s father’s near-attempts to destroy him; his later being kidnapped at gunpoint by two homophobic would-be murderers and jumping out of the bed of their truck at 70 miles per hour; and his journey across and around the country to end up a naturalist-slash-survivalist living on the mountain above us, not to mention the profound spiritual war of his family at the center of the narrative, the first feeling to hit a reader of this book is shock that its narrator is still alive.

I’m not too into psychedelics, and the drugalogs that come from them, particularly from the highly covered freewheeling 1970s. But Rush uses these effects as mere lighting, through which the story of the memoir, its spiritual searching, its familial trauma, its sensitive and sexy storytelling and gender experimentation, all take center stage. The memoir landscape is rife with addiction stories, often focused heavily on the substances abused, but it would be amiss to presuppose this as yet another. It’s not about drugs; instead, it’s the story of a boy with such sensitivity, sensuality, and insight into his family, yet also too young and too captured by the idealism of the 60s to see the horrors awaiting him at every turn, or the coming landslide of the next decade. Had he been a little older, or less brave in his sexuality, or less influenced by the familial disease of alcoholism, he may not have dove so headlong into the crashing waves of danger. And if such were true, we would be bereft the lucid miracle of this literary masterpiece.

I wanted to talk to him about how he managed to come through the tsunami of the wildest memoir I’ve read, not only alive, but seemingly improved. How did he write a first book in such dazzling, sparkling prose—so incredibly deft in execution, so precise and artistic in naturalistic descriptions—and so loving in human portraiture? How did he get brought from the desert, to share with us this light?

“It’s actually a love letter to my mother in a very fundamental way,” Rush says of the book, at dinner the night before we would head to that desert. “Because she was in an impossible situation. She was married to my enemy. The person I love more than anyone in the world is married to my enemy. Well, what the fuck do you do with that? The punk solution is kill her, kill him. But in truth, you don’t do that. You take care of them when they get old.”

Does he have something the rest of us don’t—forgiveness, compassion?—or rather, possibly, is he something the rest of us aren’t? “I think what happened is this: Because I waited 40, 45 years to write this material, the hotness of my emotion had cooled down a little,” Rush says, suggesting the former.

And then, with a few more words, opinion swings to the latter: “But then something really magical happened. Now, I’ve never written anything else in my life, some love letters, some grant proposals, some bad poetry. But in writing I made just the most extraordinary discovery, that I fell in love with my characters. And the more villainous they were, the more I loved them, the more I wanted to know more about who they were and what I could remember and what did it mean. It was fascinating. And I understand now why we need Cruella de Vil, why we need the worst of Dickens. It just brought the story to life. I suddenly remembered so much through the agency of the people who hurt me and confused me. But I no longer had the hurt. So I was able to go in and really appreciate who they were.”

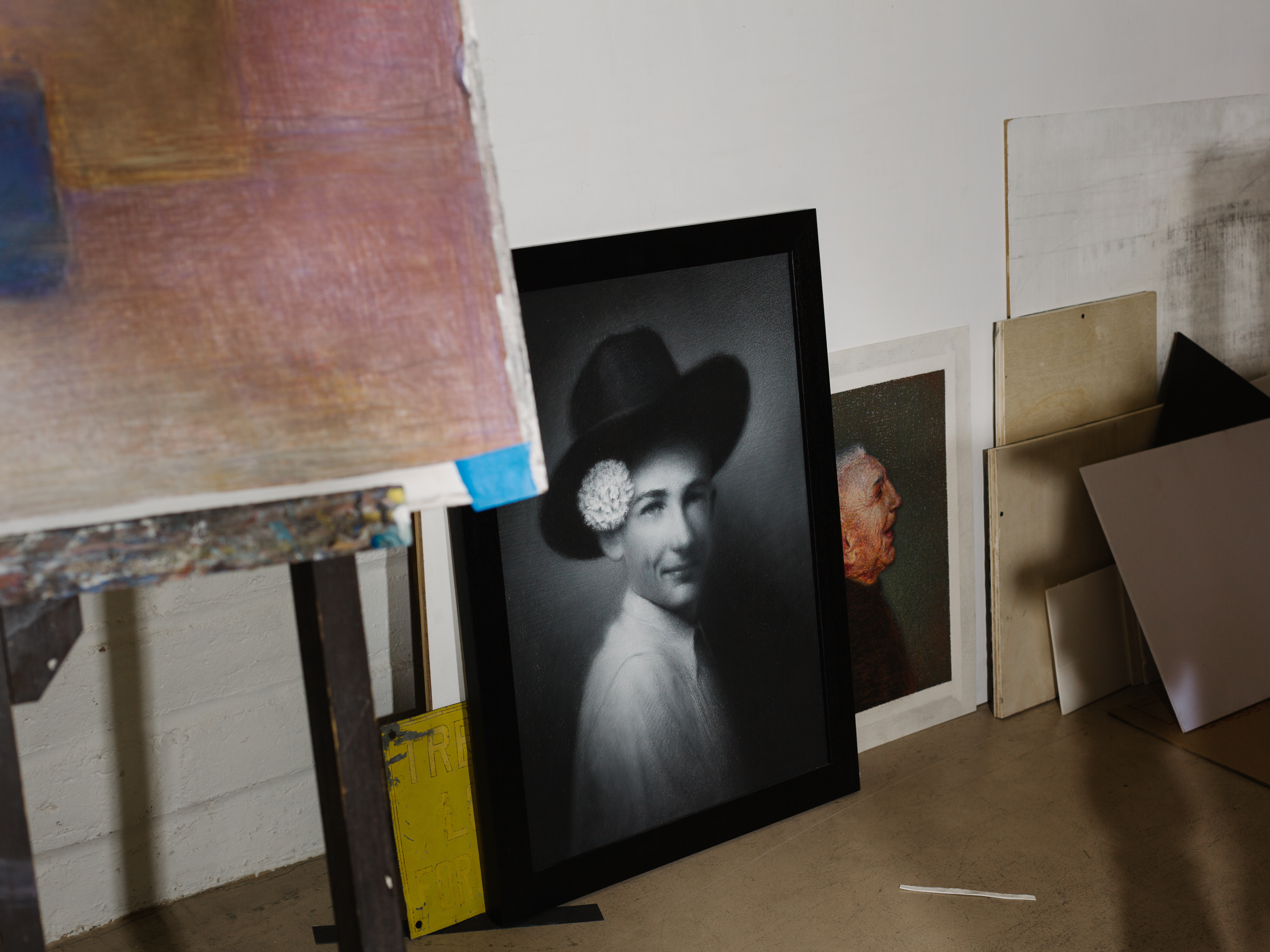

I met Rush for the first time the night before the photo shoot, at Penca, in downtown Tucson. The chic Central Mexican restaurant was filled with the din of well-to-do patrons, among whom Rush, still a local, is a known entity. His intricate and photorealistic charcoal paintings hang on its walls, mostly portraits of family members. In memory, there’s a five-foot painting of an elfish boy wearing a white shroud with a flying saucer-shaped mushroom on his head on one wall, a haunting photorealist portrait of Rush’s father on another. On a different wall, I see a distorted, bandaged head from some anthropologist’s nightmare, and a beautiful black androgynous model with a pink headpiece of silk or brains, wearing a blue-beaded necklace.

"There is one line in the book that is very close to how I see life. My friend Sean, he’s mocking my beliefs, and I say, I would rather believe in too much than too little. And that is how I look at life.”

“The discovery that I made when I was in the mountains; I thought I was weak and it turned out I was strong,” he says, sitting at the table, smiling and pursing his lips playfully. “Well, this was the thing they had withheld from me, is I didn’t know that was my birthright. I didn’t know that I was actually a really tough person. My favorite word in reviews of this book is ‘bad ass.’ Because once I realized I was bad ass and could do fucking anything, life changed. But it took me a long time, because I had taken on everybody’s bullshit that because I was a fag, I was a fairy. And I was fairylike in any number of ways, but I was actually tough as nails.”

Rush is consistently placid about what he has gone through. “One of the reasons I am tough and have made it this far is not simply that I had struggles, but that I was allowed to benefit from them. A lot of it kind of sucked, but the fact is, you know, it’s not safe to throw a child in the swimming pool and say ‘learn to swim.’ It’s not safe, but sometimes it works. I wouldn’t advise doing it. But I’m an experimental baby. I’m at the confluence of the Eisenhower years and Timothy Leary.”

And in keeping with his elegance, he also doesn’t expect others to share the beliefs he holds, doesn’t evangelize. “The approach I’ve taken in the book across the board is relatively agnostic, in regard to God, the Devil, UFOs. You’re not required to join me in what I believed as a child. There is one line in the book that is very close to how I see life. My friend Sean, he’s mocking my beliefs, and I say, I would rather believe in too much than too little. And that is how I look at life.”

For Rush, drugs and God were never to be feared, even at the darkest point, while living at home and selling heroin out of his parent’s basement. “I worked so hard to believe I existed, that I was a solid being, and the needle always undid me—the ease of its entry, like a hand passing through a ghost,” he writes in The Light Years. “But the high was irresistible—the dark bliss, the low note, the sleep cure. In heroin, I found absolution—all my sins were erased. Suddenly a warm ocean was rolling out to meet me.”

The drug traffickers from the memoir still exist, and Rush told me about where each of them is now. Some are dead, like the man in the memoir who pointed a loaded gun at Chris’s head 40 years ago, spun the cylinder, and pulled the trigger over and over, and attempted to kill him for his sexuality. Somehow, in keeping with the persistent and uncanny spirits in the memoir and Rush’s life, the bullet was always missing in the chamber.

“Why do men in the memoir and in life want to kill people like you and the other ‘soft boys’?” I asked, using his term for himself and the young queer men he had various relationships with over the years.

“Because they see something of themselves that they don’t like,” he says simply.

Standing in the river, the author follows instructions for poses. “Lift your chin higher”; “Turn your face into the sun to avoid the raccoon eyes”; “Spread your arms with your palms upturned.”

Rush laughs.

“Oh, you want the transfiguration pose,” he says, his slightly nasal New Jersey voice full of humor. He is beautiful while being photographed; he hasn’t lost the glamour of his pink Pucci days. As he poses, eyes closed, he looks a little like Joan Crawford—but his beauty is more like Udo Kier’s from My Own Private Idaho. I see Christopher Walken appear in his glinting blue eyes, Tim Robbins in his stature and gait, and Robert Kennedy in the face. I think he's a shapeshifter.

I wonder if he is one of the people from other planets he went looking for as a teen. In the memoir, after he stopped searching full time for Jesus on entheogens, Rush describes going to Los Angeles to see the infamous UFOologist Gabriel Green. In Green’s library of occult manuscripts, Rush writes that he studied mystery schools, aliens, and occultism. He was the subject of taped past life regressions under Green’s leadership, then became Green’s model in photo shoots. At this point, he was only 17.

Rush is characteristically uncritical of the situation. “My visit with Gabriel Green was really on the up and up. I don’t think he was a liar. There was a very genuine transaction between us. I would say he was probably flirting with me; I think he was just so excited to have someone young and curious in the house. It’s very hard to say. He had kind of a high squeaky voice [at this point, Rush mimics Green’s voice]. It was a little peculiar. He was very fastidious, he read the paper slowly, he read everything, he was a great cook. He took me to an ashram, and everyone loved him. ‘Oh, Gabriel’s here.’ I loved it because there was a ton of free food."

Later, he is more analytical. "What did I learn in that library? I learned a set of questions."

At dinner, I asked Rush what he’s the most nervous about in terms of the book’s release, when all of his complicated past will be out in the world. He explained he loathes one question people ask him: How do you remember everything when you were on drugs so much of the time? “It’s like people saying, if you remember Woodstock you weren’t really there, which is the most idiotic thing I’ve ever heard.”

But asked how he accessed the memories, he will answer, explaining that he relied on his “very good memory” but also extensive interviews with his family and friends, after he’d written down his story first (“I had to understand my own point of view before I could go out and talk to whoever was still alive”). “I nodded to novelistic techniques in trying to tell a story that has a rationale, has a meaning, has a center. And there was a real struggle to try and find that thread in my own memory and that’s one reason that it took ten years.”

Rush explains the technique of “the palace of memory” to me, a term I’ve not heard before. He advances that memory is holographic, explains that in the distant past people needed to memorize entire books, and there were strategies to do it. A person would place different parts of a book in different rooms of a palace in their minds, then walk through it and retrieve these memories. “In a way it was giving memory, a substance, a form, and dimension. And I realized, Oh, that’s the way the mind really works.”

His mother, in spite of the “classic enabling” and constant blind eye she presents in the memoir, also kept records and letters; these were key to how his book unfolded.

“They’re the only documents I have that are my state of mind at that time,” he explains. “And also what was really important to me was my language at the time. Early on I made a decision that I think was fateful: I decided I didn’t want to write it from the adult point of view. I wanted to stay as close as I could, not 100 percent, but I wanted to be in the kid’s mind. To think of things the way he did, because otherwise it was going to be me justifying and explaining, and telling you what really happened, and I thought, No, that’s not authentic to the rush of the story.”

For a moment under the direct sun, Rush seems to have a mohawk on his prognathous and outright heroically shaped head, like a Szukalski sculpture. Here is the side of him that went punk in New York City after the memoir’s timeframe ends, quite suddenly. Nine years after living up on the mountaintop, and three or four years after overdosing from eating a jawbreaker of nearly pure cocaine during his heroin addict years—burning out his kidneys and almost dying in a heart stopping series of scenes—Rush moved to New York.

Rush tells me he is writing his next book about this time, which was seemingly less fraught than his early years. “I went to FIT and came under the tutelage of Omar Torres, who was then-house designer for Bulgari, and probably the greatest jewelry designer of the late 20th century. He saw my portfolio, said very little, handed me a card and said, 'Call this number in ten days.' I did.

“Long story short, I became house designer of a very secretive, French firm that worked as a hired gun for the five big houses and built fabulous jewels. At age 26 I got to work with really marvelous materials on marvelous projects. Over the two years I worked there, before I founded my own company, it became obvious that Omar was grooming me for one of the big slots. And it was fascinating, but I was… too young… too rock 'n' roll… too horny... It was vulgar for me to be designing jewels for the ultra rich while my friends in the ghetto were dying of AIDS. I just couldn’t focus. Soon after I became a painter.”

We’d spent the hour before the shoot inside a cave. In it, I want to know more about everything: about another big and otherworldly reveal, that his mother slept with his father’s brother. How his parents' marriage survived in spite of his father catching them in the act. His parents' lost fortune. How he interprets the meaning of both of his dad’s brothers dying from crashes involving different dump trucks in incidents occurring nine years apart. As any captivating, crawling true story prompts you to want more, I'm hungry for it.

In response to my queries, Rush ventures, “As the polish poet Szymborska said, the most interesting and exciting answer is ‘I don’t know’… I’m not looking for the final conclusion. The profound discovery for me was the questions.”

I ask Rush how he wants to be perceived in the press, if he’d like to be seen as a person who believes he’s in touch with mystery schools, extraterrestrials, and higher forms of consciousness.

“A little tiny bit,” he says, very seriously. “But the problem is—and I think I’m probably a little oversensitive to it because I’ve read the New York Times too much—there’s a deep stripe of intellectual skepticism among the great writers. There is a lot of skepticism in the modern plan right now. And I’m not a skeptic. However, I don’t want to cross over into kook. Can we, like, skip the kook part? Because I am not a skeptic, and I’m not sure about anything. I’ve never needed to be sure. I’m an artist. I have inclinations; I have notions; I have intuitions. That’s plenty. And so it’s tricky. I certainly have interests and experiences. But I have no agenda. I have no mission. I have no statement on all of it, really."

Rush refers to painting and writing as “advanced technologies.” For 30 years now he has been working in these technologies, while partnered to author Victor Lodato, who was a major figure in helping Rush with revision, feedback, and the terrain of selling the memoir.

At dinner, Rush wouldn't tell me specifics about his adult connection to aliens, mystery schools, or other realms of consciousness that he acknowledges he can slip between often, but he kept intimating that I knew. In the desert, I watched the intensity in his eyes, the same intensity I’d imagined were in his father's eyes while reading The Light Years. In fact, I felt I'd seen his father in real life, probably because I was sitting last night across from his photo-real charcoal portrait.

His father was beyond handsome, kind of terrifying in a Gothic, almost vampiric sense, with a criminality in the eyes. He was a Korean War vet, and I’ve seen one of his dog tags hanging in Rush's painting studio across town on a white wall over a nail. The wall also holds a chipped painted frame around a black-and-white photo of two young men standing naked on a carpeted floor before a scrim of what looks like black paper. The men are dancing, or wrestling, their asses pale from swimsuits, their left hands raised and joined, right arms wrapped around the other’s.

Charles George Rush was the child of immigrants, an Irish Catholic in a sibling-hood of alcoholics, with an unbelievable story between he and his brothers, which we finally learn about three quarters through The Light Years.

When I first meet the younger Rush at dinner, I say, “I love your father,” risking a very serious faux pas. I wait to see how he will respond. I’m not sure how Rush feels about him, as the man nearly killed him in so many ways.

In the memoir, his father Charlie regularly calls his son “cunt,” a “queer,” and a “fag,” tells him to close his legs, and attacks him physically, punching Rush in the mouth. “Don’t be silly, they adore you,” a character says to Rush at one point, speaking of Rush’s parents. “My dad pointed a gun at me. And a knife,” Rush responds.

His father is also the reason Rush is sent away time and time again, during which he becomes the drug test subject, indoctrinated by dealers, and, of course, is nearly killed repeatedly. He is not exactly the hero of the memoir, but there are moments so pure and full of the force of life, and others where Rush and his father’s fates are so inextricably bound, their relationship almost brotherly and twinned in addictions, that I find myself loving him.

Dad was more of a mystery—a dark planet, exerting only vague astrological influence on his offspring. He walked with a limp, a steel brace on one leg from the car crash of ’64. He was still strong, though, and steady. He could be quite charming, always ready to amuse guests with a story or a joke. But to a child, to a son, he had nothing to say. He seemed unsure around kids, uncomfortable, even guilty. I knew something bad had happened to him, something that couldn’t be talked about.

There was always silence in his wake.

Every Sunday, our family went to church, but Dad went during the week, as well. He went to confession often and took Communion every day. I was intrigued by the idea of his soul—and even more intrigued by the idea of his sin. What could it be?

Reading over the passages of his father’s abuse, I wondered how I could tell Rush I loved his father. But that is the remarkable miracle of the old “technology” of writing. Over a long enough spectrum of experience, and with the eyes of a good enough artist, even the sins of hatred and violence can be absolved by the miracle of human love and familial forgiveness. And after I do tell Rush I love his father, his demeanor softens, he smiles, laughs maybe. “I love him, too,” he says. “You’re the first person who has said that, and I’m really thrilled to hear it.”

Rush says that he hit a wall when researching his father. “He confided in no one. By the time I started to write he’d been dead a number of years. He left no emotional trace other than confusion. And so I really didn’t know why he did a lot of the things he did. And no one could tell me. I talked to everyone who knew him. I learned very little. I realized that uncertainty is a tremendous force in literature that it can’t be in painting. I’m a painter. It’s very hard to paint the invisible. But that’s exactly what literature does well.”

Rush tells me about the man in the last scene of the book, before the epilogue, who cyphers for who he himself really is. It is 40 years ago, and Rush is sitting in a hot springs in the Tucson mountains we’d find ourselves in the next day, with a strange naked old man missing one eye, the hole going right through his skull.

Rush says that that man might have been the Devil, a character in the memoir who at one point takes the form of a panther that he encounters on the mountain, the animal inadvertently saving his life. I don’t know if that’s true that the old man was the Devil. But I do think that love is really what we are here for: When someone writes and recreates for us the entire kaleidoscope of their family drama, lovingly recasting the specter of the dead and the now aged as they once were, that is love. That is a highly advanced technology indeed.

After the shoot, back at Rush’s art studio, I say my goodbye to him and go to the Arizona Inn, where the culmination of the book’s most violent episode takes place. When Rush was 15, a shitty rich kid from his second boarding school wanted to get kilos of marijuana from the Christian dealers in Tucson, and took him on a diabolical road trip to get them, finally completely dumping him in the middle of nowhere.

Rush had to hitchhike to find his sister, which is when he was kidnapped at gunpoint; rather than be raped and or killed, he jumped out of the back of their pickup truck at 70 miles per hour. The leap and impact pulled the skin off much of his body, and left him unconscious until he awoke in a hospital bed. He tells me his mother took him to this hotel afterward to recuperate.

The inn is big for Tucson and pink, somewhat of a miniature distant cousin of the Beverly Hills Hotel. It was built 20 years later, in the 30s and the furniture remains from that era; inside, there are gilded mirrors, giant floor-to-ceiling bookshelves behind wavy glass, old couches and very old carpets, the kind of antique botanical prints you’d expect. I feel stifled imagining coming down from so much time on LSD and after living with Bible-drag trippers out in sci-fi stash houses in the white hot desert, among saguaro and ocotillo, to end up with my mother looking like Betty Draper, in a hotel full of the Victorian-influenced furnishings of the rich. Also, I admit to myself, I feel let down alone without Rush.

But he seems to have a more forgiving eye. I wonder if after the harsh assaults, the molestations and anger, alienation and abandonment, and the grueling expansion of drugs, being mothered in a nice hotel wasn’t heavenly.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Luke Goebel is an author who lives in Palm Springs and Los Angeles.

All photographs by Daniel Tepper. You can follow his work here.

from VICE https://ift.tt/2uDHuTS

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment