It’s been 50 years since those infamous hot nights in June 1969 when LGBTQ patrons at the Stonewall Inn fought back against a brutal police raid. What started out as a spontaneous attack on a New York City gay bar turned into a multi-night uprising in the streets of Greenwich Village.

Those nights have been widely credited as the birthplace of the modern-day LGBTQ rights movement. While there’s no denying Stonewall was a key turning point for the movement, it was not nearly the first notable confrontation between LGBTQ people and police.

In the early 1950s, there was a burgeoning movement of gay men, lesbians, and transgender peope fighting for their civil rights. Since then, historians have documented more than thirty LGBTQ demonstrations, sit-ins, protests, and riots that occurred in the U.S. in the years leading up to the 1969 Stonewall uprising.

Here are just five of those important protests worth remembering alongside Stonewall.

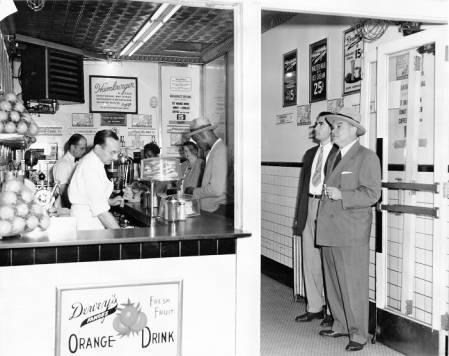

Cooper’s Do-Nuts Riot, Los Angeles, 1959

In May of 1959, LGBTQ customers rioted at a 24-hour cafe in Los Angeles called Cooper’s Do-Nuts after being harassed by a group of police officers. Because cross-dressing was illegal at the time, police could use the presence of drag queens or transgender people in an establishment as the basis for making an arrest or raid. And that’s exactly what they did.

That night, members of the Los Angeles Police Department attempted to arrest two drag queens, two sex workers, and a gay man cruising other patrons, according to most accounts. One of those arrested was novelist John Rechy, who wrote about the incident in his now-classic debut novel City of Night. In an interview with historian Lillian Faderman, Rechy recalled onlookers throwing coffee cups, doughnuts, and trash at the police until he and the other detainees were able to escape.

Having taken place ten years before Stonewall, this incident is considered one of the earliest known LGBTQ uprisings in the U.S.

Dewey's Restaurant Sit-in, Philadelphia, 1965

Influenced heavily by the Black civil rights movement and demonstrations like the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycotts and the 1960 Woolworth’s lunch counter sit-in, LGBTQ people became more defiant in their political activism during the 1960s.

"As the homophile movement of the 1950s grew stronger into the 60s and 70s,” says Marc Stein, professor of history at San Francisco State University, “LGBTQ people began to feel emboldened and discovered the courage they needed during a powerful period of social movements." One example is the earliest known LGBTQ sit-in, which took place on April 25, 1965 at Dewey’s lunch counter in Philadelphia. The eatery had become a hub for LGBTQ people in Philly, but that spring, staff began denying service to any customers who appeared to be gay or gender non-conforming. On April 25, approximately 150 people were denied service for that reason, according to Stein’s City Of Sisterly And Brotherly Loves: Lesbian And Gay Philadelphia, 1945–1972. But three teenagers decided that they wouldn’t leave.

The police were called and the three were arrested, in addition to Clark Polak, a gay-rights leader in Philidelphia who rushed to the scene to help the three protesters obtain a lawyer, and was subsiquently arrested by police. All four were found guilty of disorderly conduct.

A week later, on May 2, 1965, three more people conducted a second sit-in at Dewey’s to protest the arrests. When they refused to leave, the restaurant owners once again called the police. This time, however, the police conceded that they had no reason to force the protestors out. Dewey’s agreed to stop denying LGBTQ people service.

Compton's Cafeteria Riot, San Francisco, 1966

In August 1966, after management and police harassed a group of transgender women and drag queens at Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco—a late-night hangout for many local queers and sex workers at the time—the city’s LGBTQ community responded with two nights of resistance.

It was not the first time that customers of Compton’s had clashed with the police, but on this summer night, clientele had had enough. "The police treated trans people and street queens with impunity. They would often be forcefully strip-searched and charged with nuisance crimes and given very brutal treatment," says Susan Stryker, director of the 2015 documentary about the riot, Screaming Queens. "There had never been any effective resistance to police harassment until Compton's."

The protest began with peaceful picketing against Compton’s increasingly discriminatory service, but police were eventually called when things got rowdy. According to accounts of the night, when a police officer then tried to arrest one of the trans women present, she threw her coffee in his face. That’s when all hell broke loose. In Screaming Queens, Amanda St. Jaymes recalls dishes and furniture being thrown all over the diner. As the fighting spilled into the street, dozens of trans people, drag queens, and gay men fought back against the police and smashed the glass windows of the restaurant.

Although smaller in scale than the Stonewall riots, which occurred three years later, the Compton’s riot invigorated the local LGBTQ community in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco to begin organizing itself. In the months following the riot, the community began to build a network of medical and social support services for trans people, which led to the creation of the National Transexual Counseling Unit in the late 1960s.

Mattachine Society Sip-in, New York City, 1966

Another pivotal LGBTQ demonstration was the 1966 “Sip-in” at Julius’ Bar in New York City. At the time, it was common practice for bars to refuse service to gay, trans, and gender-nonconforming people. Although there was no law explicitely sanctioning the descrimination, bars had the right to refuse service to “disorderly” patrons, and at the time, being homosexual was enough for many people to consider you disorderly. On April 21, Dick Leitsch and two other members of the New York chapter of the Mattachine Society, one of the earliest gay rights organizations in the U.S., decided they would try to change that.

In an effort to bring scrutiny to the regulation, the group, along with four newspaper reporters, headed to Julius’ Bar in Manhattan, where a man had been arrested for “gay activity” a few days prior after being entrapped by a police officer. The bartender poured them drinks when they arrived. But, as Leitsch recalls on an episode of the podcast Making Gay History, when they identified themselves as homosexuals, the bartender placed a hand over one of the glasses and said, “I can’t serve you if you’re gay. You know that.” That moment was captured in a now-iconic photo by Village Voice photographer Fred McDarrah, which later ran in the newspaper.

“We are gay people and we just want to be served food and liquor, and we are orderly, and we intend to remain orderly,” the group responded. “Please serve us.”

“For Dick, entrapment was the single most important issue for the gay rights movement to tackle. If you can’t get together in public places without risk of arrest, you can’t live your life,” says host and historian Eric Marcus on Making Gay History. “If you were a gay man in New York City back then, wherever you went, you risked falling prey to an undercover police officer doing his very best to trick you into letting down your guard, and showing an interest in him. Back then, an arrest like that spelled personal, professional, and financial ruin for many.”

The demonstration ultimately lead to two lawsuits that struck down the New York State Liquor Authority’s practice of taking away liquor licenses based on bars having queer clientele— opening the door for gay bars to begin opening and thriving in the city—and an agreement by New York City Mayor John Lindsay to end entrapment practices by police in gay bars. While these practices weren’t totally wiped out by these victories, they did decrease.

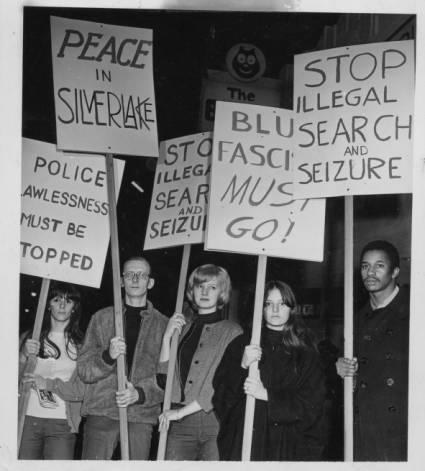

Black Cat Tavern Riot, Los Angeles, 1967

On New Year’s Eve 1966, the newly established Black Cat Tavern on Los Angeles’ Sunset Boulevard was filled with LGBTQ people ringing in the new year. That was until undercover police officers who had been waiting in the crowd began arresting patrons for exchanging midnight kisses. Police brutally beat several of the patrons and detained 16 people that night, two of whom escaped. As detailed in the Faderman’s Gay L. A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, And Lipstick Lesbians, the police chased the men down the street to a bar called, New Faces, on Sanborn Avenue. There, the officers assaulted the club’s owner and beat her two bartenders unconscious. One of the bartenders, Robert Haas, suffered a ruptured spleen from the attack. Once he recovered, he was charged with felony assault of a police officer. Six men were later changed and found guilty of lewd conduct that night at the Black Cat Tavern.

Six weeks after the raid, on February 11, 1967, 200 people gathered at the Black Cat to peacefully picket outside the bar in protest of police harassment and brutality.

The demonstration was organized by a group called P.R.I.D.E. (Personal Rights in Defense and Education), who became inspired to publish a newsletter called the Los Angeles Advocate. It eventually transformed into a nationally distributed magazine known today as the Advocate.

from VICE http://bit.ly/2LbTmG5

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment