On Tuesday afternoon, Jake Berman got an email from Etsy informing him that one of his listings had been removed from its website for copyright infringement. Berman makes his own versions of transit maps, which he meticulously designs over hundreds of hours of work.

But his New York City subway map, according to Metropolitan Transportation Authority lawyers who filed a takedown request under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, was a violation of the MTA's copyright for its own subway map. Berman, they contended, could not sell his version.

When he got the notice, Berman felt “a little bit of disgust and a little bit of disbelief,” he told Motherboard in an interview, because “it requires a certain amount of audacity on the part of their lawyers to say that something that somebody else created is actually the MTA's property.”

Indeed, experts are puzzled by the MTA’s copyright claim. For one, Berman’s map is clearly not a copy of the MTA’s subway map. But even if it was, it’s curious the MTA, which has an operating budget of $16.6 billion for this year alone, would concern itself with the piddling revenues lost from one subway map sold on Etsy.

“The basic question [for the MTA]” offered Thomas Kjellberg, an intellectual property attorney with the law firm Cowan, Liebowitz, and Latman, “you guys really give a shit?”

In a statement, MTA spokesperson Shams Tarek said the agency reviews potential copyright infringement issues on a case-by-case basis. He added Berman’s map has “been copied from our intellectual property which we have an obligation to protect on behalf of the people of New York.”

Arguing over the intellectual property of maps is as old as America itself. For almost as long as this country has existed, maps have been copyrighted by their makers. The Copyright Act of 1790 covered “any map, chart, book or books already printed within these United States…” before adding a whole bunch of conditions.

What is not protected work under copyright law, Kjellberg said, are facts. For example, the MTA cannot copyright the fact that there is a transit station at Union Square and that the 4,5,6,N,Q,R,W and L lines stop there. Nor can it copyright the general location of a stop when plotted on a map, the direction in which it runs, geographic entities like the island of Manhattan, or the names of streets.

What they can copyright is what Kjellberg termed as “the expression of facts.” In other words, do they look the same? Does one incorporate the design elements of the other? Or are there “substantial differences?”

Berman created this particular version of the subway map after—what else?—a frustrating experience with the subway. He had just moved to New York and was waiting on the platform on a weekend for the B train for half an hour. This was how Berman learned the B only runs on weekdays. So he decided to make a subway map of his own, one that, among other things, clearly marked which trains do not run on late nights or weekends.

After more than 300 hours of work and 15 or 20 different iterations, Berman finished the map and shared it online for others who might find it useful. But he didn’t sell it until about a year and a half ago, when he noticed, in what is now almost too ironic, that someone else had copied-and-pasted his map and was selling it on Etsy.

“I said if this guy is making money selling my map,” Berman recalled, “then so should I.”

The map didn’t generate much revenue for him, but it made enough to buy friends beers every once in a while and give him a tangible sense of accomplishment. His map is now the first displayed on the New York City Subway Map Wikipedia page, right next to the official map. Berman said it felt good to create something people liked.

The MTA didn’t see it that way.

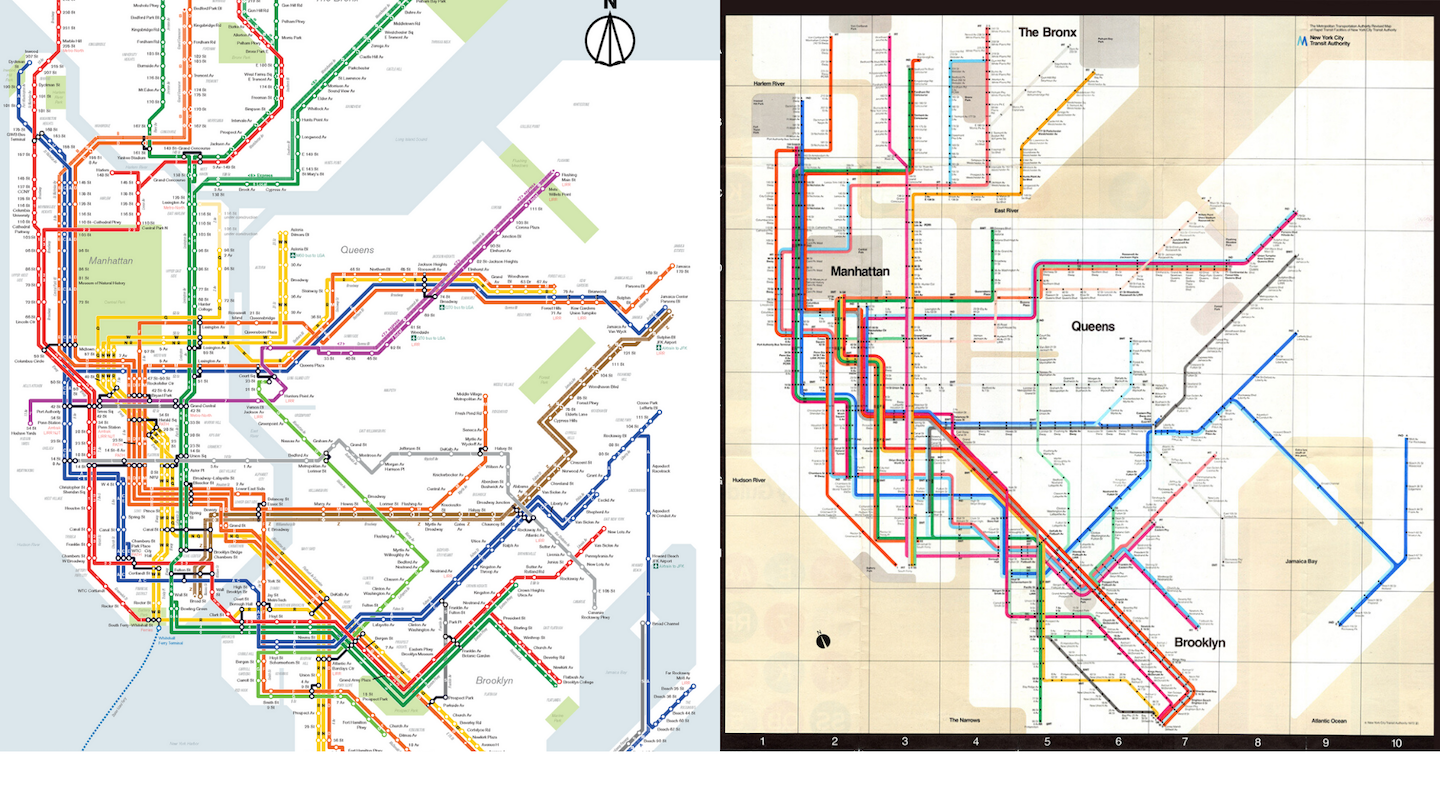

Lester Freundlich, an attorney for the MTA, told Berman in an email Wednesday that his subway map was “clearly a derivative work of MTA’s current version of the Vignelli subway map.”

The Vignelli map is not the one you see plastered in stations and on trains. It was created in 1972, but was quickly replaced because riders hated it so much. Only seven years later, the MTA moved on to a completely different map, a variation of which is still used today. The Vignelli map was largely annexed to transit map history until 2011, when the MTA brought it back from the dead.

The MTA uses the Vignelli map for The Weekender, a quasi-neglected digital interactive map that helps riders navigate weekend service changes (other than the weekly service changes, the app has barely been updated since the day it was launched and has a 1.4 rating in the App Store). In other words, the MTA resurrected the Vignelli for the very same reason Berman created his map.

“Yes, there are minor differences between your map and the MTA map,” Freundlich wrote in his email. “But given your access to the MTA map on the MTA website, and the substantial similarities of your map to the MTA map, the only rational conclusion is that your map is based on the MTA Vignelli map.”

But there is a potentially critical flaw in that logic. The MTA created The Weekender in 2011, two years after Berman created his map, which he uploaded to Wikipedia in 2009.

Even so, Berman thinks his map stands alone on its merits. “Even assuming that I had a time machine,” he wrote via email, “they're not the same thing.”

To prove his case, Berman listed eight differences between his map and Vignelli’s. For example, they display lines running along the same route differently. Berman uses different symbols for trains that only stop on nights and weekends. Vignelli uses “gentle curves” whereas Berman uses “hard angles.” Berman shows streets and labels neighborhoods. They use different colors and shapes for geographic landmarks. He went on, and added that he could have continued to go on for much longer.

“In general, the only major similarities are that both are subway maps and both use 45-degree angles in our diagrams, which has been standard transit map practice since 1933,” Berman asserted. “It’s certainly not copyrightable.”

For his part, Kjellberg looked back and forth at the two maps while on the phone before concluding Berman would have “a pretty good argument that he doesn’t infringe on copyright because there are some very substantial differences,” but added it’s “not a slam dunk.”

The MTA only sent a takedown notice to Etsy, neglecting to contact Berman directly about the shop he runs where the map is also available. The map is still on sale there for $50. The MTA declined to comment on why it only issued a takedown notice for Etsy.

Other than Berman’s map, there are currently 271 other results on Etsy for New York City subway maps, not to mention the scores of other independent mapmakers who sell their own versions on personal websites.

As for what happens now, Berman responded to the MTA’s takedown notice with a counter notice of his own, as permitted under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Kjellberg explained the MTA has 10 business days to sue in federal court, or else Etsy is legally obligated to put the map back up for sale.

For all the takedown notices the MTA sends out, it very rarely sues. Out of curiosity, Kjellberg performed a search in a Bloomberg database of federal lawsuits where the MTA is a plaintiff to see if they get litigious when it comes to copyright claims. He said the MTA has never sued anyone for copyright infringement as far back as the database went, which included cases since 1992. That doesn’t quite comport with what the MTA told the New York Times in 2013, when it said it has gone to court in a copyright case “only once...to challenge a deli called F Line Bagels in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, in 2005. The sign out front now reads just Line Bagels.”

That article also claimed the MTA received $500,000 a year in licensing revenue, a whopping .003 percent of the agency’s 2013 revenue. In fact, two Long Island Railroad foreman—an agency within the MTA—made more than that in overtime pay.

The MTA may have thought it could scare off one independent artist from selling a subway map on a popular platform, but it may have miscalculated. In yet another ironic twist, the MTA picked the wrong artist. He has a day job.

“I'm an attorney by trade,” he said. “So this is something I know something about.”

from VICE https://ift.tt/35zJGf1

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment