The Great Barrier Reef, the largest living structure on the planet, appears to be on the brink of yet another devastating mass bleaching event driven by prolonged exposure to extreme heat.

Between 2016 and 2017, half of all corals on the Great Barrier Reef died due to stress and starvation caused by back-to-back heat waves that were amplified by climate change. Only the southern third of the reef was spared significant losses during the disaster, which permanently degraded the ecosystem’s northern reaches.

Unfortunately, recent weather forecasts suggest that southern sanctuary—along with the rest of the Great Barrier Reef—may be in for another bout of heat-induced bleaching. While current models suggest the carnage won’t be quite as intense as it was three years ago, coral suffering is likely to be more widespread.

“We’re looking at an event that’s going to be far north all the way to the south,” said Mark Eakin, the coordinator for NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch Program. “You’re looking at a bigger, more widespread event.”

For the past few weeks, the Great Barrier Reef has been running a fever, with temperatures along the 1,400 mile-long ecosystem hovering a degree Celsius or more above normal. At these temperatures, corals become stressed and start to bleach, jettisoning the colorful algae that provide them their food and turning a bloodless white. If the water remains warm for too long, the algae won’t return, and the corals will starve.

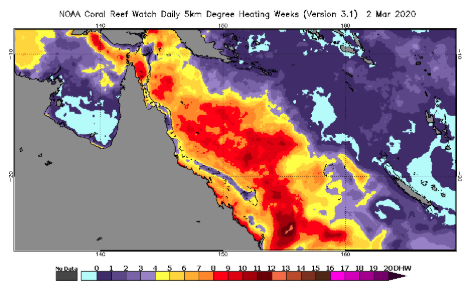

Experts worry the Great Barrier Reef is now uncomfortably close to that tipping point. Vast swaths of the ecosystem have reached eight “degree heating weeks,” a metric scientists use to describe how long corals have been in the slow cooker. In layman’s terms, it’s “where we expect to see widespread bleaching and significant mortality,” Eakin said.

Already, Eakin said, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and others are confirming bleaching up and down the reef.

“NOAA’s latest bleaching forecasts are devastating,” Terry Hughes, director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University, wrote in an email. He warned that the event is still building: “It’s likely to peak near the end of March if temperatures stay high,” he said. At the end of the month, Hughes will be conducting aerial surveys of the reef to determine the extent of the damage.

Following the last mass bleaching-induced dieoff, research led by Hughes determined that nearly a third of the 3,800 individual reefs comprising the Great Barrier Reef were transformed into a “highly altered, degraded system.” The worst deterioration occurred in the north, which lost a large proportion of the branching and table-shaped corals that create the 3D structures that reef-dwelling fish depend on for habitat.

Given the latest forecasts, scientists worry the south could fall into similar ecological disrepair. “The south didn’t bleach in 2016 or 2017, and the corals there are physiologically naïve and very vulnerable,” Hughes said.

At the same time, as coral reef scientist Kim Cobb of the Georgia Institute of Technology pointed out, another year of severe bleaching on northern reefs that are still limping along from the last event could further hamper their ability to recover. “Seeing [these events] happen in such close succession is alarming, frankly,” she said.

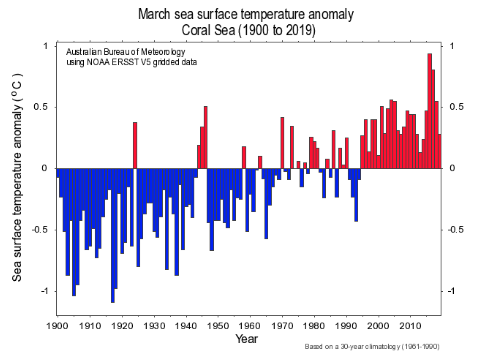

Climate change is playing a key role in these recurring heat shocks. Since the mid-1990s, March temperatures in the Coral Sea where the Great Barrier Reef is located have been running warmer than average, making it easier for a heat wave to push corals over the brink. A rapid attribution analysis conducted as the mass bleaching event was unfolding in April 2016 concluded that global warming dramatically increased the likelihood of the hot weather spell that preceded it.

Worldwide, the situation doesn’t look much better. A 2016 study examined global satellite temperature data and found that 97 percent of coral reefs have experienced warming since 1985, with 60 percent “warming significantly.” A paper published in 2018 found that globally, the frequency of coral bleaching events has quintupled since the 1980s, leaving reefs less time to muster a recovery in between.

For these jewel-toned underwater jungles, heat death is fast becoming an occupational hazard of life on Earth.

“It’s a sobering reality we’re in,” Cobb said. “We’re looking at a wholesale reorganization of global reef ecosystems, right under our eyes.”

“We never imagined that three mass bleaching events could occur within a 5-year period as early as 2016-2020,” Hughes added. “Climate change is here and now—not some distant threat at the end of the century.”

from VICE https://ift.tt/3cvjW8t

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment