For five years, Tariq has been a full-time Uber and Lyft driver in New York City. Each year, Tariq has watched his wages slump and his expenses climb. He’s added more hours and days to what was once a 40-hour, five-day work week. Even in the worst moments, though, he never found himself sleeping in his car like some of his driver friends regularly did. Until the “lockout.”

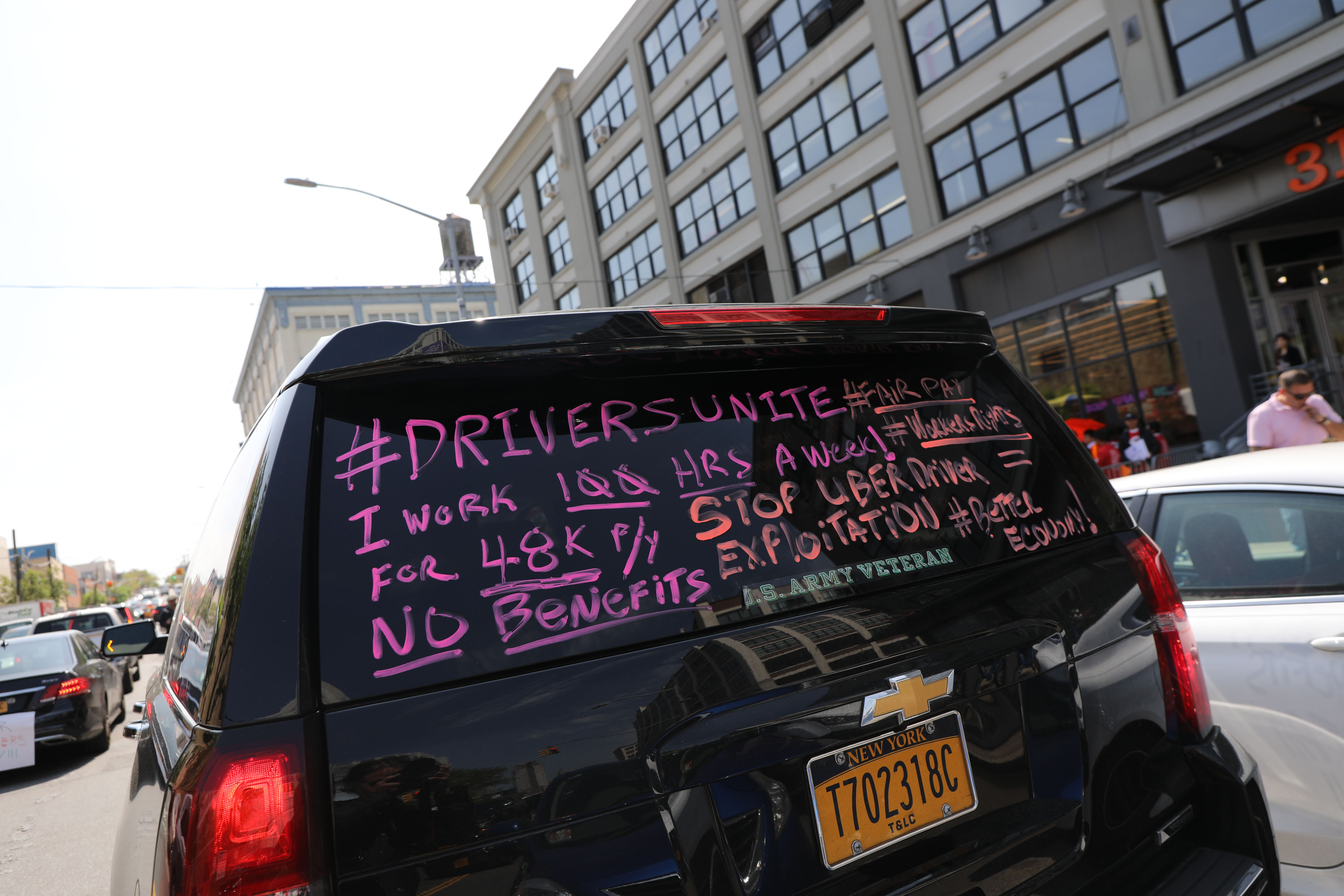

Over the last few years, Tariq joined two groups that represent rideshare drivers: the New York Taxi Workers Alliance and the Independent Drivers Guild. Both labor groups promised to leverage their large memberships into direct action that would pressure City Hall into finally improving working conditions for ride-hail drivers like him. Their activism led to the introduction of a series of landmark regulations from the New York City Council and Taxi & Limousine Commission (TLC) in August 2018: a cap on the number of ride-hail vehicles, along with a pay floor that promised to drastically improve driver pay.

Almost immediately, ride-hail apps tried and failed to challenge these regulations in court. Over the past nine months, however, they have successfully undercut these rules with a new tiered quota system for drivers. In an attempt to avoid having drivers collecting wages while being underutilized by riders, Uber and Lyft have restricted the number of drivers who can log on at any given time, with preference given to drivers who drive the most.

Ever since these changes were first introduced, Tariq has been sleeping in his car to meet the quotas. It’s not that he’s homeless. Because he has fallen below the top tier of drivers, he tries to be in his car constantly, even if he’s not being paid, so that if he’s suddenly allowed to log on, he can take advantage and have a better chance of moving up the tier system.

“No matter how hard I work, it’s never enough. Every day is about how to get online so I can hit the quota and not be locked out,” Tariq told Motherboard. “Where do I spend hours parked in the day? Where do I spend hours parked at night? When do I use the bathroom? When do I eat? If I hit the quota, I can relax. I can drive whenever I want. If I don’t hit the quota, I get locked out.”

He’s fallen behind on his rent, car insurance, and vehicle payments, putting him dangerously close to having the vehicle remotely deactivated then repossessed.

“I don’t want to sleep in my car, I don’t want to spend most days away from home. But I have to,” Tariq said. “If I don’t hit the quota, I don’t get the right to log on and drive whenever I want. If I can’t drive whenever I want, then I get off-peak hours which means no customers. Which means no money. Which means I spend more hours in my car trying to hit the quota and make a living.”

These changes, called the “lockout” by drivers, have fundamentally changed what ridesharing is. Uber and Lyft have long said that drivers have the flexibility to choose their own hours—this is, in fact, core to their argument that drivers are not “employees” but are instead independent contractors. But new Uber and Lyft policies in New York City not only mean drivers can’t make their own hours, and an increasing number of drivers are driving a minimum of 60 hours a week to avoid having their hours cut on the app.

In conversations with more than a dozen drivers, I learned of a multi-faceted crisis: a failure of the TLC to enforce its own ride-hail app regulations, an unsustainable rat race among drivers to meet the increasingly demanding quotas of Uber and Lyft, poor working conditions in which drivers who supposedly make their own hours have less agency than workers at traditional workplaces, growing financial insecurity, and a rapid decay in the physical and mental health of drivers caught in between exploitative gig platforms and ill-equipped bureaucracies.

All of this, of course, is exacerbated by the ongoing coronavirus crisis, which puts drivers on the front lines of a city that is “social distancing” and avoiding public transit.

Motherboard has granted anonymity to rideshare drivers who spoke to us for this story, because many of them expressed fear of retribution from Uber and Lyft. Names of drivers have been omitted or changed.

Even drivers who say they like the lockout have a pretty bleak view of what’s happening: “Whether we hate it or love it, this is capitalism in action: strong drivers over weak ones, the wheat from the chaff,” one driver said.

*

Ride-hailing apps have had a simple strategy in New York City: growth at all costs. By 2019 there were well over 120,000 for-hire vehicles (FHVs) on the road—fewer than 40,000 FHVs existed before Uber’s first NYC experiment with ride-hailing in 2010. As of January, Uber and Lyft make up roughly 97 percent of the city’s daily trips—a far cry from January 2015 (the start of TLC’s data collection), when Uber provided 60,000 daily trips compared to NYC yellow cabs’ 450,000 daily trips.

In a 2019 press conference celebrating victory over the ride-hail companies after new regulations were imposed, Bhavari Desai—executive director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance (NYTWA) labor group—spoke plainly about why she and City Hall were opposed to Uber and Lyft: "Uber and Lyft and their cohorts created a race to the bottom, filling our streets with so many vehicles that no driver could get enough fares to make a living."

Exponential growth, whether in a petri dish or the United States' largest city, is not sustainable. For years, studies have reported the same set of outcomes when ride-hail apps are mass adopted: worse traffic conditions, increases in urban pollution, mass migrations from public and private transit, all paired with bleak unit economics that constantly cut wages while hiking fares. Uber’s commitment to growth manifested differently in its various markets across the world, but in New York City the strategy meant a vicious battle with the city itself. When Mayor Bill de Blasio tried to introduce a vehicle cap in 2015, Uber hired an army of lobbyists and consultants, launched “DeBlasio’s Uber” featuring 25 minute wait times, and “convinced” the Mayor a study would be best.

For the next three years, the city adopted a relatively laissez-faire approach to ride-hail apps even as it became clear these apps were wreaking havoc on the city and its communities. It took a wave of driver suicides, in-depth coverage of New York City’s taxi medallion bubble, protests and campaigns led by labor groups like the Independent Drivers Guild and NYTWA, and a June 2018 study of proposed pay rules by economists James A. Parrot and Michael Reich to push the TLC to consider action. It’s worth mentioning that the 2018 edition of the TLC's report to the City Council was the first to specifically mention Uber or Lyft—three years after the city’s first effort to regulate the company.

In 2018, City Hall overwhelmingly passed two regulations. The first regulation was a one-year vehicle cap aimed at not only easing endemic congestion, but blocking the flood of FHVs spilling into the streets. The second regulation was permanent pay floor regulation meant to raise the sub-minimum wages which were driving some drivers into despair.

This pay floor used a company’s “utilization rate” as part of a dynamic formula that set payment minimums. The TLC defines a utilization rate as “the share of time drivers spend with passengers.” The thinking here was that, without government regulation, an explosion of unutilized cars would lead to increased congestion and would continue to push wages down as more drivers would be driving without passengers (and thus without fares).

The Parrot-Reich study found that 96 percent of all high-volume FHV drivers made less than $17.22 hourly ($15 after expenses). They proposed to fix that by calculating each company’s utilization rate, then plugging it into a per-minute and per-mile minimum trip payment formula.

Each company’s specific utilization rates were abysmal: In 2017, Uber and Lyft had a 58 percent utilization rate, while it was 50 percent for Juno, and 70 percent for Via. The incentive, then, was to use utilization rate in the pay floor formula to stop perpetual growth and have drivers spend less time on the road empty, hopefully reducing congestion as well. The lower the utilization rate, the higher the per-trip pay floor. Without these rules and incentives, Parrot told Motherboard, drivers would “continue to subsidize the company as they buy vehicles, maintain them, and drive for sub-minimum pay."

“Before the vehicle cap, the companies were just signing up drivers right and left. That was clearly unsustainable and needed to change. So the [New York City Council] supported a cap on vehicles—the cap didn't come from the Taxi and Limousine Commission, it wasn't their regulation," Parrott said. "The TLC maintained its position that they didn't have the authority—clear-cut authority—to act on their own. So they proceeded to get a handle on the volume of cars to regulate the pay and encourage regulation of vehicles by the companies. It was a set of policies that weren't coordinated from the beginning."

After the vehicle cap and pay floor were passed in 2018, a one-year study of the effects of the vehicle cap and the pay floor’s utilization rate on congestion was carried out and completed by summer 2019. The study’s conclusions made the case for the TLC to propose not only indefinitely extending the cap but adding a “cruising cap” to limit how much time app-based FHVs could drive without passengers in Manhattan south of 96th Street. Within six months, app companies would need to reduce their cars’ time spent idling from 41 percent to 36 percent, then down further to 31 percent within another six months.

Altogether, the regulations promised to radically change the lives of most app drivers by increasing their income, reducing the time they spent empty, and improving working conditions. Already, Uber and Lyft had stopped accepting new drivers because the vehicle cap and pay floor made the companies, not the public, bear the brunt of the cost of perpetual growth. Lyft had tried and failed to block the vehicle cap and pay floor in court, and the cruising cap would surely draw fire from both, but the mood was high when Mayor de Blasio signed laws that made the vehicle caps and pay scheme permanent in June.

“With this new policy, New York City is holding companies accountable for the underutilization of drivers and oversupply of vehicles that have choked the city’s streets,” said Acting TLC Commissioner Bill Heinzen at the time. “This innovative approach represents a major win for our hardworking drivers and the city as a whole. It shows how cities nationwide can take back control of their streets.”

“A cap on new For Hire Vehicles was the first step in stabilizing incomes for drivers in poverty, debt and despair across the industry. And with the minimum payment rates that followed, Uber and Lyft drivers are finally able to see gains,” added Desai, executive director of the NYTWA. “Uber and Lyft and their cohorts created a race to the bottom, filling our streets with so many vehicles that no driver could get enough fares to make a living."

In all the fanfare, however, regulators overlooked the fact that Uber and Lyft became big precisely because they ignored regulations. By the end of the year, both Uber and Lyft were able to kill the cruising cap through the courts. To fight the new pay rules that used low utilization rates to increase driver pay, however, the apps would have to get more creative.

*

It took Lyft two weeks to undo years of work that made the vehicle cap and pay floor possible. On June 27 of last year, Lyft told its drivers it was introducing a “priority to drive” system: “the number of drivers who can be on the road at any given time will be determined by passenger demand—and spots may be limited. This means if there’s low demand, you may have to drive to busier areas or wait to go online and drive once demand picks back up.”

To achieve and preserve priority to drive, drivers needed an acceptance rate above 90 percent and to complete 100 rides in 30 days. Drivers without priority would only be allowed to drive when there was enough demand. (An exception would be made, however, for drivers who rented a vehicle from Lyft through its Express Drive program, which drivers have long bemoaned for its resulting high costs and low pay.) According to TLC data, the average number of ride-hailing trips per Lyft vehicle in June 2019 was 96. In October, Lyft raised its priority to drive minimum to 180 rides every 30 days. At the time, the average number of trips for Lyft vehicles that month was 113.

In a statement to Motherboard, a Lyft spokeswoman said: “We have said that the TLC’s rules are misguided. To comply with them, we had to make changes to the app, and are working hard to support drivers through these changes.”

In September, Uber announced it would be introducing its own version of priority driving: a “Planner” that would allow drivers to schedule trips for the next week depending on what tier of its quota system a driver achieved last month. In one early communication, Uber pinned the blame on the TLC: “We know that all the changes to the city's regulations since 2018 have been frustrating to drivers, and we're doing our very best to support you as we work to respond to the TLC's rules."

The first tier of drivers would be allowed to go online anytime, but only if they completed 1,000 trips in three months or 250 UberBlack/SUV (luxury) trips. The second tier of drivers, who completed 700 trips or 200 UberBlack/SUV trips in three months, were allowed to reserve shifts in the Planner at 10 AM every Wednesday. Drivers who completed at least 400 trips or 150 UberBlack/SUV trips were slotted into the third tier, allowed to reserve Planner shifts on Thursday at 10 AM each week. Every group was expected to maintain a 4.8 or higher rating; the fourth and final tier comprised drivers who either did not have a 4.8 rating or did not hit the third tier's quota. They would be allowed to reserve shifts after Friday at 10 AM. TLC data indicates the average number of monthly ride-hail trips per Uber vehicle at the time was 191.

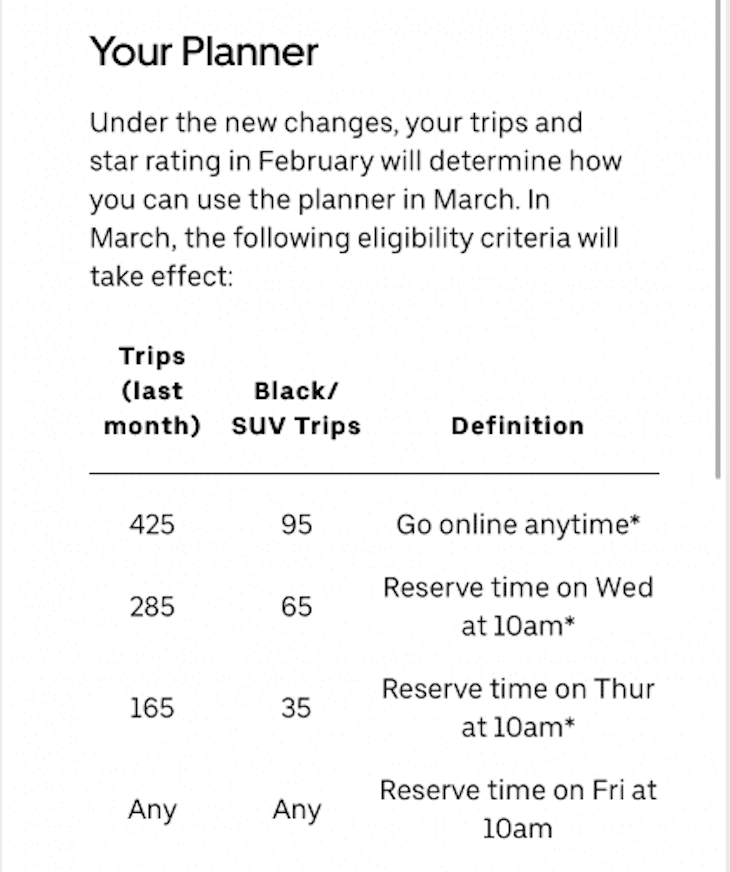

In February, Uber sent drivers details for its new quota starting in March, which are much higher than the previous quotas: 425 trips or 95 UberBlack/SUV to go online anytime; 285 trips or 65 Black/SUV trips to reserve on Wednesday at 10 AM; 165 trips or 35 UberBlack/SUV trips to reserve on Thursday at 10 AM. Again, each tier would require at least a 4.8 driver rating and anyone below the lowest quota tier or a 4.8 driver rating could only make reservations on Friday at 10 AM. By the end of 2019, TLC data reported that the average number of trips per Uber vehicle barely inched to 214.

To go online anytime, drivers have to complete an average of just over 14 rides per day, assuming a 30-day month and that they drive every single day. That means drivers in the top tier work a lot and need to continue working a lot. But they aren’t the ones who have been screwed the worst by this system.

For any driver who is not already in the first tier, it requires a herculean effort to move into it, and it can require a lot of unpaid time sitting in the car. Drivers are given a number of reservation slots—each one allows a driver to log on for one hour. The number of reservation slots drivers are allowed to has fluctuated from 23 to 17 to 14 to 11, and now seven for some. As each tier is allowed to register, there are also substantially fewer slots to reserve; there are weeks when Thursday reservations see either only off-peak times, low-demand times, or no slots at all. If drivers want to make up the difference, they are forced to sit in their car on the app constantly and hope that there will be a shortage of drivers somewhere, sometime, in the city that will unlock their access to the app. For most drivers, this means 60 to 70 hour weeks, every week, to hit a higher tier.

Essentially, many drivers are living in their cars, hoping they’ll be allowed to log in often enough to be able to move up the tier system.

"Uber can control when I work, where I work, how much I get paid. I’m tired, I’m sick, my body hurts and I can’t live like this anymore."

"In the past, I would only drive five or six hours on weeknights, then maybe 10 to 12 hours on weekend nights for extra money. But now, I'm mostly driving 12 hours every day and I'm only taking one day off,” one Uber driver who has been working in the city for two years told Motherboard. “I am scheduling shifts, I am forced to constantly go where Uber needs drivers, I don’t get to control what I do. Not only that, but now I drive 30 to 40 percent more now—and I'm not breaking even by any means. Before the lockout, on average I was making $1,500 each week after vehicle expenses if you include insurance, vehicle rentals, gas, cleaning, all that. Now it's $500 in a good week. I can’t live on that, but I’m trapped paying off this car that I got to drive Uber in the first place!”

After repeated requests for comment, Uber declined to answer detailed questions from Motherboard. Instead, it sent the following statement: "As a result of regulations passed by the TLC and actions taken by one of our competitors, we began limiting access to the driver app in areas and times of low rider demand."

Uber and Lyft’s new policies fly in the face of what they have always insisted is the core of their business model and worker classification: flexibility. At the same time, the New York City experience suggests that there has always existed a core tension between the viability of Uber’s business model and the autonomy (and livelihood) of its drivers.

“Obviously you can’t continue to grow 50 percent a year, indefinitely, forever and ever. When the pay standard was approved in 2019, the market had stabilized. In other places, it's not clear that the growth is continuing in an unsustainable fashion,” said Parrot. “There was this early period where the companies were trying to portray the industry as something where drivers can drive whenever they can please, but that was obviously a myth.”

For years, Uber has always maintained that profitability is just around the corner. At times, it has been necessary to invoke the specter of autonomous vehicles as proof of its inevitable profitability. Its loudest critics, however, have always maintained that not only is Uber a fundamentally unprofitable company but that it operates on bleak unit economics which can only ever improve its margins by cutting driver compensation or hiking fares. This tension between flexibility and profitability becomes clearest, then, when cities like New York block Uber from cutting driver compensation.

“In less regulated markets, Uber's rhetorical claims that drivers are free to log in and logout or free to work at their own discretion are directly contradicted in a city like New York,” said Alex Rosenblat, research lead for Data & Society and author of Uberland: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Rules of Work. “The lockouts make it more explicit that Uber is controlling scheduling. Technically, drivers still have the option to secure shifts in advance, but of course if they can't make those shifts or they try and log in outside of those shifts, then their chances [of getting work] are spontaneous."

Rosenblat’s ethnographic research of ride-hail drivers over the past few years has focused on “algorithmic management,” or the ways in which the Uber/Lyft model of work actually resembles, and in many cases goes further than, traditional dynamics of employment: "I would argue that they're currently controlling labor in lots of ways. By choosing how many drivers to onboard into a given market. By setting the rate that drivers earn—by perennially changing them and often cutting them. By changing the requirements for vehicles. By monitoring their behavior at work, from how quickly they're accelerating to how harshly they're braking, to threatening drivers if they don't perform according to the behavioral standards that were set. That's the basic tenet of the algorithmic management argument.”

*

In conversations Motherboard had with Uber and Lyft drivers around New York City, there was near-unanimous hatred for the lockout.

“If you don’t already have priority, forget it. It’s not worth it. And by the time I can reserve shifts on the Planner, the busiest slots are already gone. The shifts given by Uber aren’t enough to hit 425 trips in a month, let alone enough to pay my bills!,” one Lyft and Uber driver said while getting ready to sleep in the back of his car. “This is the only way. My entire life revolves around this stupid app if I want to eat, to sleep, to do anything. This isn’t living.”

Feelings ranged from accusatory, with drivers blaming not only Uber and Lyft but New York City regulatory authorities for taking too long to do something the apps broke within a few months, to dejected, as drivers either accepted living in their cars to “earn” the right to drive whenever they wanted or made plans to exit the gig economy industry and find another line of work.

Another driver who’d spent the last three months sleeping in his car in order to take advantage of any demand spikes, was irate when Motherboard met him, specifically because of Uber’s sudden increase in the quotas. “My plan was to work like a slave every day for half a year, maybe more, until I could save enough money to never do this shit again,” he said. “OK, Uber can control when I work, where I work, how much I get paid, alright fine, six months. But I’m tired, I’m sick, my body hurts and I can’t live like this anymore.”

"I would like people to think about the lives of the drivers. Ask what happens to a person when they cannot sleep, cannot eat, cannot shit on their own time. Whether Uber or Lyft or Via or whatever stupid app is worth it."

One driver, Rafael, fancied himself as a sort of “crisis entrepreneur” and explained that “Uber and Lyft are doing this because they fucked up by hiring too many drivers, but they’ll fuck [up] again and cause too many drivers to leave, meaning people like me will be there to eat when there’s too much demand and not enough supply.”

“Supply” is exactly what Uber’s co-founder and former CEO Travis Kalanick called drivers internally years before Uber began scheduling drive shifts in a Planner to minimize labor costs. When that fact was pointed out to Rafael, he responded, “There’s no harm in having clear eyes about how they see us. The real harm comes from people acting out some fantasy of ‘being their own boss’ when the apps control nearly everything.”

While a consistent theme among drivers was the recognition that their labor—and how, when, or where it was used—was not exactly theirs to control, what varied widely was how drivers then rationalized that reality.

"I think no one wants to go to work every day feeling disempowered, right, and I think people often come up with other narratives or other ways to describe their circumstances—usually positively," said Rosenblat. "I think what we are also describing is a very masculine way of approaching work, where you're going to sort of 'take it on the chin' and you're going to self-sweat because you've got a family to support."

Work on these platforms is always thought of in terms of these entrepreneurial narratives that tend to obscure core tensions between flexibility and profitability, or between autonomy and algorithmic management.

"Whether or not you can handle the work is very different as a question than whether you should be deprived of workplace protections, or whether your employer should be providing extra levels of protection,” Rosenblat said.

*

As Veena Dubal, a law professor at UC Hastings, observes in her case study of the California taxi industry, Drive to Precarity, these conditions are a feature, not bug, of the ride-hailing industry everywhere. When comparing modern conditions to those of pre-union San Francisco taxi workers who struck in 1919, she writes they too "had no set income, paid for their own gasoline, and drove with no regulatory limit on competition. As an additional regression, the [ride-hail] drivers also had to drive their own cars, bear the costs of wear and tear, purchase gas and insurance, and pay for vehicle upkeep."

The Uber model is a return to the norm, not a deviation from it. And with little to no focus on worker classification in New York City, other forces become the target of drivers’ rage and frustration. Drivers take for granted that the “greedy apps,” as some called them, are architects of their misery, but are also quick to blame other drivers, the TLC, the political establishment, and the media. Drivers often expressed frustration that despite the deluge of reporting on poor working conditions, multiple studies empirically proving subminimum wages, a wave of suicides among app-based drivers and traditional taxi drivers, all the exposés on the fundamental exploitation that underwrites the UberLyft business model, and fierce rhetoric from politicians along with rounds of uncoordinated regulations, things have only gotten worse.

“I think the scheduling of drivers is going to be a permanent feature. Otherwise, it’s just that the companies would be leaving it to chance that the supply of drivers is going to match the demand for trips,” Parrot told Motherboard. “There’s a cost to the companies in missing the mark: if they don't have enough drivers, they can’t service demand that exists and lose market share to other companies; if they have too many drivers scheduled at any given time, then they have makeup pay to satisfy the pay standard.”

“There are too many drivers on the road. That, plus not enough demand, plus new minimum wage laws, plus the crooks at the TLC too scared to cap the number of drivers, and what do you get?” one Uber driver who has worked in New York for five years told Motherboard just before he quit driving for the company. “The apps are doing the dirty work for the city. Uber and Lyft get to save their business, the TLC gets to save face, a few thousand drivers get to starve and a few more get to kill themselves—who cares? That's why they haven't enforced the rules for almost a year now!”

The TLC declined to comment on the record for this story.

Drivers have little hope for a fix to this issue. If anything, evidence suggests this development may be permanent, as Parrot suggested earlier.

*

Since Uber and Lyft stopped accepting new driver applications in April 2019, both apps have each lost over 8,000 drivers. Tariq is now one of them. After years of eking by and after months of sleeping in his car, he can’t take it anymore.

"I can’t lie and say I hated every moment. I like driving, I like talking to people, I like the silence you get sometimes. For me, it was a perfect job on paper. On paper,” Tariq told Motherboard. “But the reality was horrible for me. So, I would like people to think about the lives of the drivers. Ask what happens to a person when they cannot sleep, cannot eat, cannot shit on their own time. Whether Uber or Lyft or Via or whatever stupid app is worth it. You get somewhere quicker, but me? I sleep in the car. I see the Planner in my dreams like I’m some robot. I want to see my daughter and my wife in my dreams. I want to see my country and my home. Yes I’m a driver, but I’m a person too!”

from VICE https://ift.tt/2UlctQV

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment