The city of Wuhan—the epicenter of COVID-19, a novel coronavirus sweeping the globe—has been under lockdown for over a month. The rest of China continues to observe voluntary (and sometimes involuntary) house arrest. A new normal has settled across the country.

Outside China, other countries are moving to enact quarantine measures, too. In the U.S., the largest cluster of cases is in New Rochelle, a 30 minute drive from central Manhattan. Governor Andrew Cuomo has called for a two week ban on large gatherings, closing schools and synagogues; nursing homes are barred from receiving visitors. The National Guard will come in and sanitize public buildings. Italy, which has the second highest number of cases outside China, has shut all museums, restaurants and bars. The World Health Organization has declared the virus a pandemic.

In Beijing, where I'm based, the streets are stilled as most people forgo the daily commute and work from home. Buses still run, but are eerily empty. Subway stations have more staff than riders. Restaurants, cafes and bars are shuttered, or only offer take-away. Plastic containers get passed through makeshift windows by gloved hands.

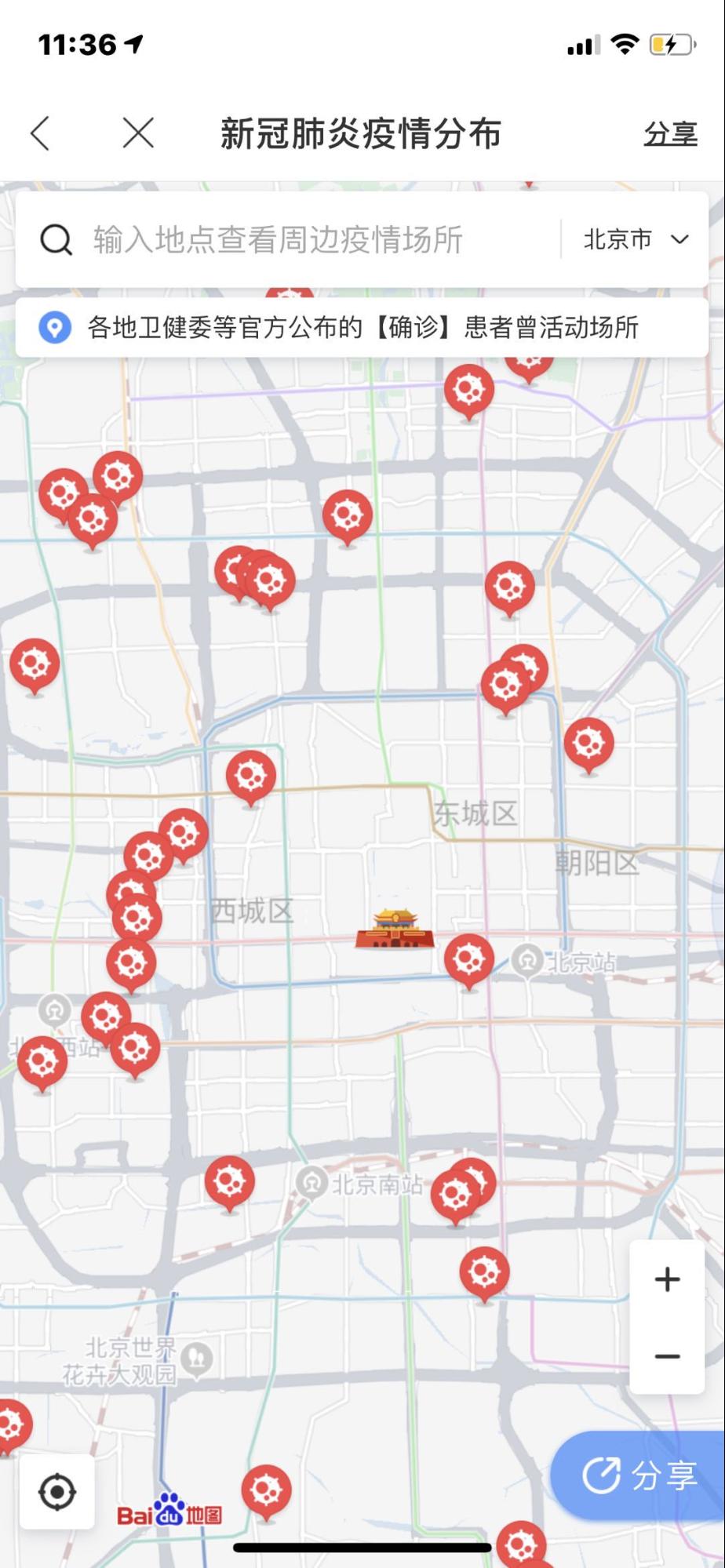

Each day there is a continual tide of reminders from family, friends, and apps to stay indoors. If you open Baidu maps, China’s most popular map app, there is an option to view the map with markers indicating which communities reported COVID-19 cases. This high tech capability is contrasted with a low-tech, cartoonish graphic of a virus. Another tab shows, in real time, the current number of infections, deaths, and recoveries.

The app also plays an audio message: “Don’t go out too much. Remember to wear a face mask. Wash hands with soap.” Shortly thereafter you receive an automated text message: “all cabs booked through Baidu maps have been disinfected, and you have an unused coupon waiting!” Then there’s a video of the sanitation efforts taken by Baidu map’s car hailing feature—over 1M cars across 40 cities are disinfected daily. With Chinese consumers suddenly homebound, businesses are trying to find ways to make people feel safe about using their services.

At home, in the high-rises, people are getting creative with their new lifestyles. Video streaming apps are in heavy rotation. And that’s in a country that already spends almost six hours a day on cell phone entertainment. Cheap smartphones, affordable data plans, and comprehensive internet coverage mean such entertainment is accessible, bountiful, and for those fighting cabin fever, a godsend. It’s one of the world’s most hyperconnected communities experiencing what may be humanity’s biggest quarantine yet.

The most popular content across China’s multiple video-streaming apps reveals how people are staying productive (or at least distracted) under sudden and prolonged house arrest. One of the biggest questions on people's minds is—how do I get a peach rump?

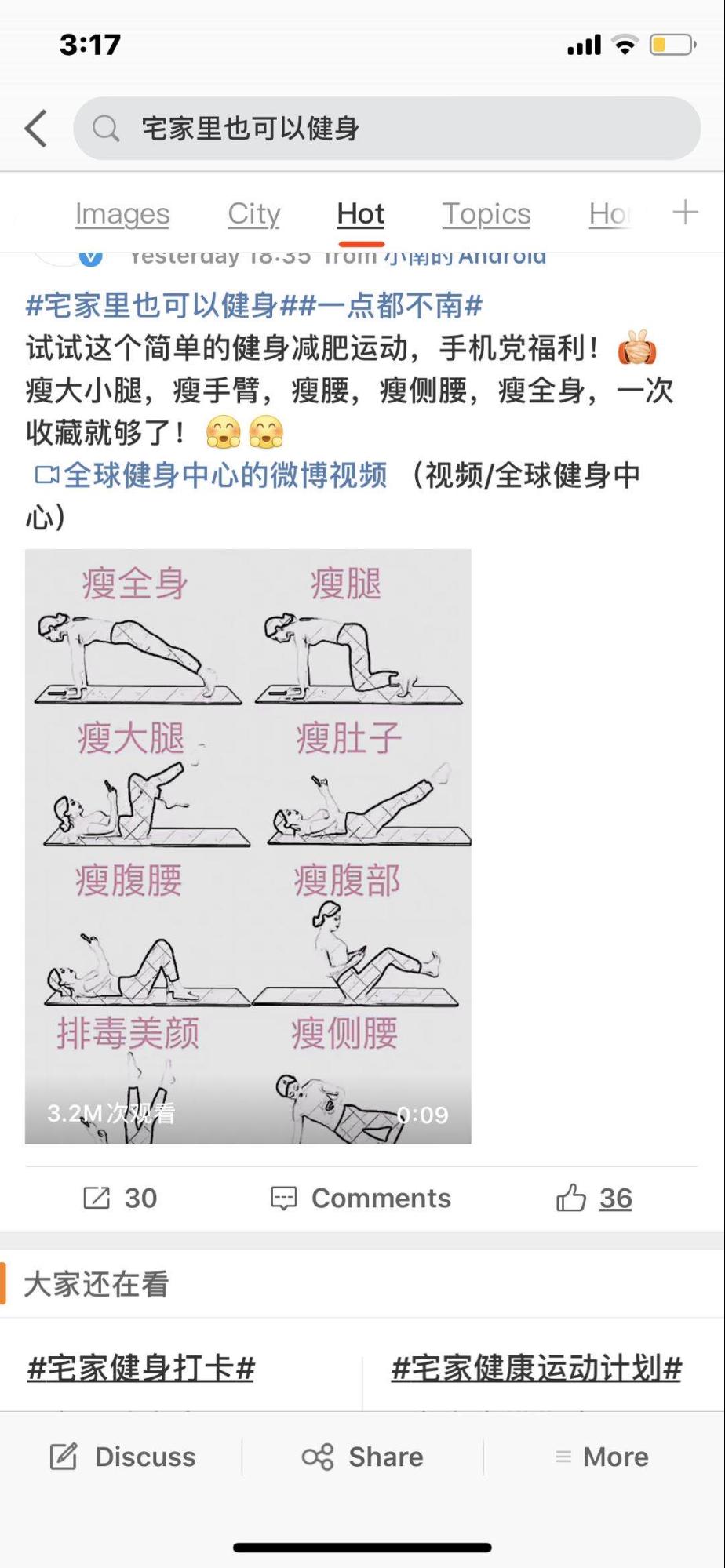

At home workout regimens are bubbling up in popularity. Currently, a recurring theme on Weibo (500M users) is about how to achieve a peach-shaped butt. One graphic, shared by over three million people, shows eight moves to achieve the effect. The movements are illustrated by a GIF showing all can be done while still looking at a cell phone—don’t miss a moment of entertainment! Other widely shared workout videos show vloggers repurposing domestic sundries in order to cobble together an at-home gym. Laundry detergent and bags of rice double as dumbbells.

Another popular hashtag is “home hairdresser.” Jerry-rigging haircuts has become a necessity as most salons remain closed. The few barbers that are open don’t see much business; people are hesitant to spend time in an enclosed space with strangers. Laminated signs promise “We have already disinfected today!”—but it doesn’t breed confidence. People would rather risk a hideous haircut. With no previous beauty school training, people turn to tools—mostly those from the kitchen. Perforated ladles are a recurring favorite, and the bowl cut is making a comeback.

Zhicong Lu, a PhD candidate in Computer Science at the University of Toronto has been studying Chinese video streaming apps in China. Lu told Motherboard that “video sharing apps can have a positive social impact on society. They allow people to stay entertained, or share information about the virus. Some videos encourage people by giving them ‘positive energy,’ like those showing how nurses and doctors are working to help the infected.”

On Douyin (TikTok in the U.S.), a video shared by more than 17 million users shows several nurses completing a hospital shift. As they remove paper hair masks, face shields, then goggles, one can see how this protective gear has left imprints and faint bruises across the women’s faces. Their hair is matted and cheeks flush. One woman complains about the smell, “geez, it stinks!”

With millions of users watching millions of videos, there’s a wide gamut of content. From the superficial to the inspiring, video streaming apps are allowing people to get in touch with the world outside their homes until the virus subsides.

Some users are finding ways to approximate human companionship. “Cloud drinking” and “cloud dining” become the top hashtags once night falls. Friends connect on a video streaming app and chat over their respective meals, beers or baijiu. Later they post videos of their digital camaraderie, highlighting jokes with canned laughter audio clips.

In a related video, one immensely lonely and creative guy rigged up various home appliances to rotate at regular intervals, and then suspended Coke cans from them. He sits in the middle of his living room, and makes toasts to his imaginary friends. After several rounds, he announces, “All right everyone, bottoms up!”

from VICE https://ift.tt/3d2HlhX

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment