The dread of the workplace looms large in pop culture, but also selectively. It reflects the fears not of people on whom the burdens of feeding and maintaining a modern society tend to fall, but of the people who enjoy just enough privileged to be spared those burdens. Charting the relationship between labor and capital through the lens of popular entertainment is therefore a mug's game. It's not a leading indicator, but a trailing one: pop culture doesn't fear what might happen, it fears that what is already happening to other people might happen to people who are supposed to matter.

The sci-fi horror classics Alien and Aliens are both concerned with how workers are viewed and treated by management. In a future where humanity is spread across the stars, untethered from Earth's history of cities, states, and other forms of government, they present a compelling metaphor for the decline of industrial labor and the victory of the multinational corporate syndicate as the world's true governing force. It's a world where humans are frozen in suspended animation for years, only to be reanimated and used, because that's what the corporation demands. The later films became less concerned with economic awareness and more invested in their mythology and the elevation of Sigourney Weaver's Ellen Ripley to heroic status, and have proven less resonant in the popular imagination. In this sense, with its focus squarely on the economic forces that have once again thrust people into the path of a merciless predator, Alien: Isolation is the only thematic sequel those first films have had. And here at the start of the Covid Depression, six years after it first came out, Alien: Isolation's moment has finally arrived.

At first, the game's attempts to update its setting put me off of it. Where the first movie is about and from the perspective of a blue-collar industrial workforce coming to grips with the fact it has been selected for annihilation, and the second movie is about a managerial class whose ambitions lie solely in advancement, Alien Isolation is about an outdated technology company failing in the wake of a market crash. It is, at first, almost transparently the work of people working in software trying to imagine themselves into the setting.

Much of the setting and early storytelling of Isolation revolves around the decline of the Seegson company and their dismal R&D outpost on Sevastopol Station, where the game takes place. Towards the end, however, it finally reveals that it is a story about what happens to the people who find their lives and livelihoods have become "distressed assets" up for auction.

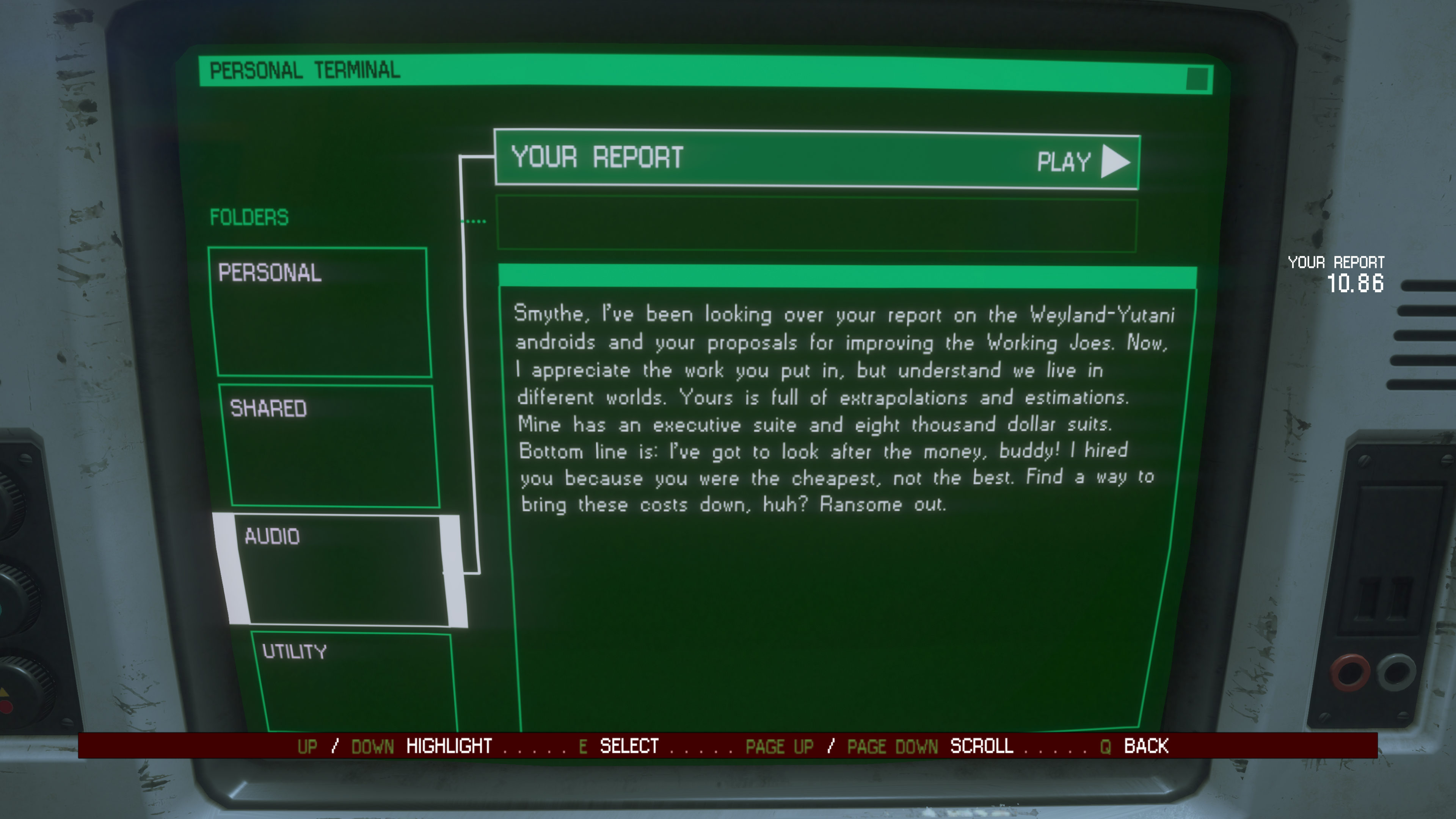

Isolation has two monsters and, in keeping with its almost too-reverent approach to its source, they are the same monsters from Ridley Scott's film. There is The Alien and there are The Androids. But the android is a hidden enemy in the first film. It is represented by a difficult new coworker whose fuck-ups are difficult to parse as either malice or incompetence until Ian Holm's Ash reveals himself by joining Ripley behind the wizard's curtain. By contrast, the androids in Isolation are patently repulsive, lurching automata. In a joke that genuinely improves as it is repeated, the hapless Seegson company has attempted to fix this obvious walking nightmare through branding. Their idea is that unlike the types of androids that can pass for human like Ash or your companion android in Isolation, Samuels, Seegson's androids are instantly recognizable. "You always know a working Joe" adorns every ad for the product, depicting elegant people looking impossibly relaxed and pleased to be waited on by the menacing golem lurking in the background of every scene. As you search through Sevastopol Station you find the dismal history of the R&D department whose lot in life was to try and salvage this failed product with minimal investment.

The Working Joes, then, become the instantiation of a particular dread associated with the software / services sectors of the economy. They are the road-not-taken in the competition to develop and dominate transformational technologies and products. The Working Joe is the PalmPilot to the seamless iPhone represented by Ash or Samuels. A similar idea, but trapped in a death-spiral of decreasing investment leading to decreasing performance leading to decreasing competitiveness until the plug is pulled entirely. The people working on the program at Sevastopol can see the problem, but are helpless to do anything to solve it (and anyone who is too noisy about pointing out the root causes gets punished).

It's unfortunate that the Working Joes eventually become contemptibly familiar. Early the game flirts with the contrast between the Joes' ineffectual solicitousness and their menacing single-mindedness. When you first meet them the question is not whether they will turn on you but when. This unpredictability is never revisited: for the rest of the game the Joes are clear enemies, and eventually they are fodder for the shotguns and explosives that are worthless against the Alien. The Joe becomes the vector through which Alien: Isolation flirts, largely unsuccessfully, with being a shooter.

That flirtation is symptomatic of Isolation's ultimate weaknesses. The plodding lethality of the Working Joes, and the clunky weaponry that Ripley can bring to bear against them, is at first an expression of Isolation's purposes. Just like in the original movie, your character is a tough survivor, but not a trained, well-equipped warrior. Weapons are mostly effective at buying time to escape. But Isolation is so very long, so much longer than it ought to be, and so the Joes become an enemy you not only have to fight, but fight in large numbers. The Alien also becomes an annoyance more than a foe, well before the game tosses a hive's worth of them at you. Isolation's early confidence as a focused homage to a lean sci-fi masterpiece eventually crumbles under pressure for Additional Content. While Isolation might be talking about economic pressures, it's also clearly a product shaped and undercut by them.

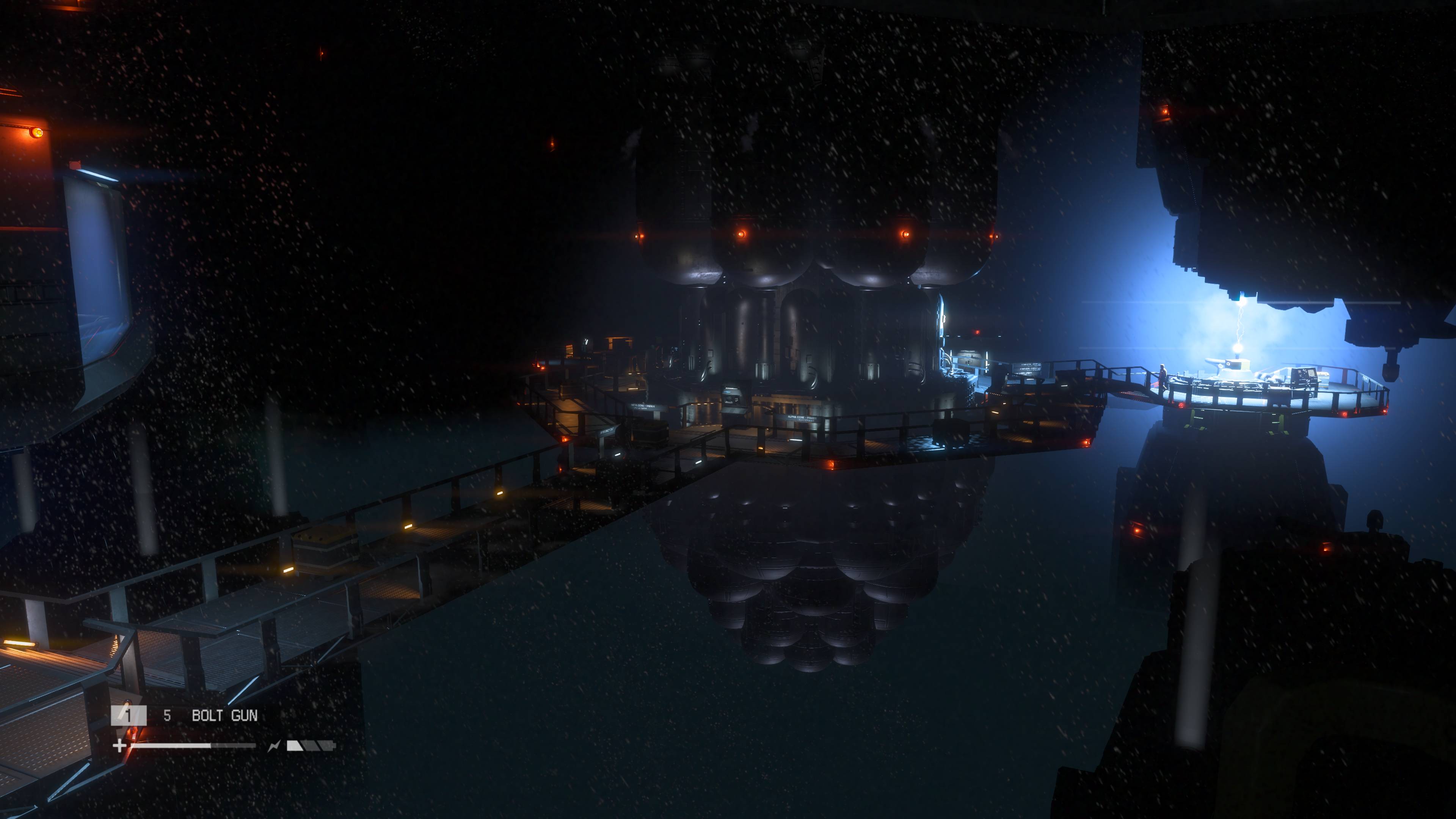

If the Joes are a product of comical corporate dysfunction, and their unsettling mediocrity an instantiation of its attendant complacency, the charnel house that Sevastopol has become is the dread horror of capital markets and the financialization of everything.

The history of Sevastopol is largely told through a series of reports filed by a journalist who was on the station as things went to hell. Her brief articles explain that Sevastopol was, from its very beginning, an doomed speculative venture on the eve of an economic collapse. Seegson bought it hoping to reverse its own fading fortunes, and now both station and company are rotting together.

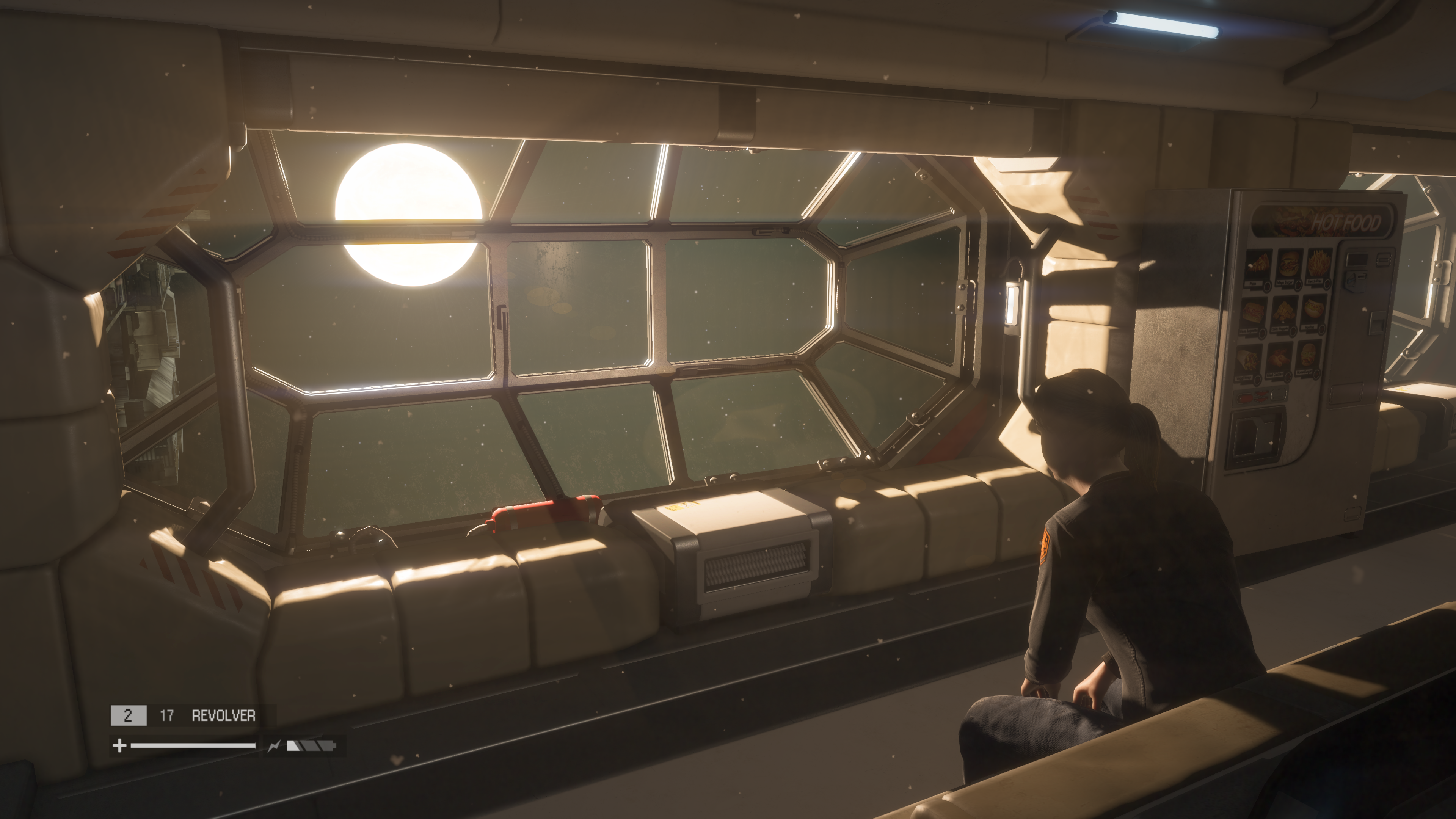

When Ripley comes to Sevastopol at the beginning of the game, the station is in the final stages of decommissioning: no supply ships arrive there nor does anyone still listen for its messages. Those remaining on the station were already living a life of rationed hardship, with nothing to look forward to except taking out resettlement loans from their own company. All of that was before an alien got loose and started slaughtering the station's inhabitants, who were so forgotten that nobody outside Sevastopol even noticed that the station had dropped off the grid.

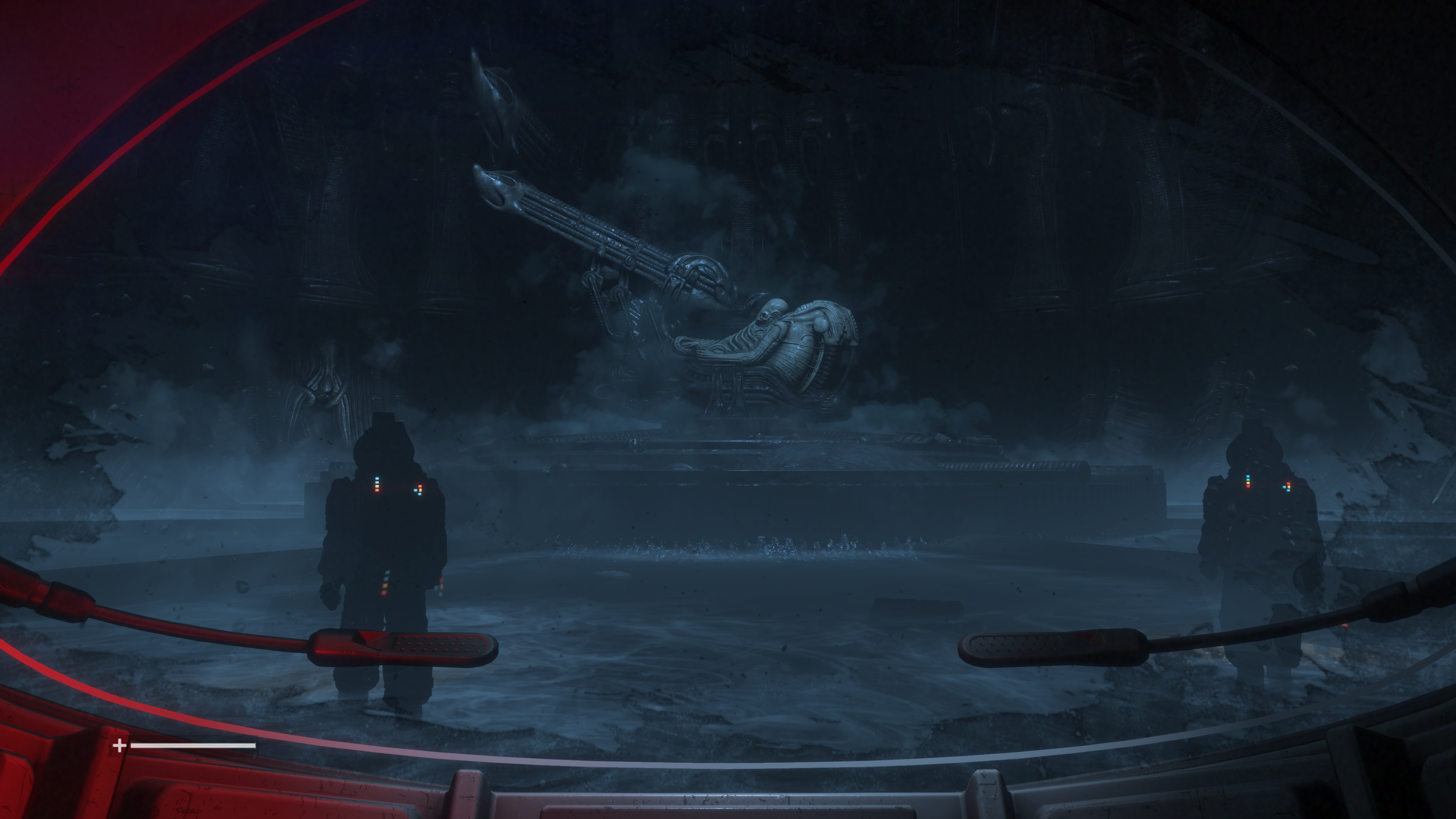

All of this is bad enough, but it's not why everyone on Sevastopol is going to die. Near the end of the game, Ripley learns that the Weyland-Yutani Corporation purchased the station the moment they suspected that it had become infested by the Alien. Weyland-Yutani never had any interest in the station. It just saw a useful incubator for the Alien.

It's not an original plot for Isolation, though originality is something the game pointedly eschews. It is instead a distillation of what the first two movies want to say: workers are viewed as little more than livestock by their corporate masters, and modern business is so thoroughly debased that it cannot perceive risk, value, or cost, merely growth opportunities.

For Isolation, the allegory is one of financial predation. The people of Sevastopol have no say in what happens to their company or its assets, despite the fact that those assets are their homes and livelihoods. Seegson's decline as a company has exposed everyone to a takeover by an investor who has no interest in managing what they have acquired, but instead in profitably destroying it. The Alien, in this case, is not a coveted corporate asset nor an expression of corporate hubris. It's a harbinger of private equity and monopoly.

It's a clever way to bring the Alien series' economic fears into the modern age without betraying its source. The high-paying industrial and trade jobs that Alien evoked with the crew of the Nostromo have grown scarce in the modern economy, and so characters like Parker and Brett, the scruffy engineers from the original film, with their confrontational assurance about their bonus pay now seem remarkable where they were once ordinary. Likewise the smarmy company man in Aliens is also a relic. There are fewer "company men" these days because so few companies give people careers and advancement. What's hard to relate to is not Carter Burke's greedy treachery in Aliens, it's his certainty that this is his big chance for advancement within Weyland-Yutani, and that advancement itself is something he'd need to earn. He's a ladder-climber, and the corporate world doesn't have ladders anymore. It has escalators that run between the top floors, and they carry the same few people upward no matter their successes or failures.

It's a mark of how the post-industrial fears of the Aliens films have given way to the more pervasive mistrust that defines late-capitalism. In the 70s and 80s the suspicion was that big business was corrupt and would place its interests over and above anyone's well-being… but it had business interests. Isolation is a product of a time when issues of ownership and interest are less clear, and when it increasingly feels like companies are being bought just so they can be creatively looted.

But Isolation might be at its most resonant right now, at a time when much of the world has been responding (with varying degrees of success or criminal incompetence) to a disease outbreak and widespread disruption to business, and it's clearer than ever that an unhealthy and distressed economy is a banquet table for those with access to capital and credit. It's a cliche to say this industry or that industry "hasn't adapted" and wasn't really healthy. But it's been hard to escape the thought over the past several years that the symptoms of ill-health are easily confused with those of poisoning. Maybe these businesses aren't getting better because the speculators who buy them on the cheap don't want them to get better.

The ultimate reveal of the two Alien films and Isolation is that the carnage was only a surprise to the people being sacrificed. To the people whose existence is only implied behind corporate logos and all-knowing supercomputers, it was all part of the plan. But the films portray a corporate logic of growth and invention, where the endgame is to create and own something powerful at any price. In Isolation we again find the reality of that universe has been adjusted to more closely resemble our own, where destruction of companies and their workers is the point.

from VICE https://ift.tt/2X3fmrI

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment