It was easy for Jana Wolf Necklace to get painkillers on the Standing Rock Sioux reservation. She developed an opioid addiction while working at her dad’s bar in Fort Yates, the main town on the North Dakota side of the tribe’s land. Eventually, she started trading alcohol to customers for pills they obtained from the reservation’s federally-run Indian Health Services pharmacy.

“There was all kinds — whatever you wanted was around here, and a lot of it,” Wolf Necklace, 43, recalled. “People would come and they would have big bottles. I would keep track of who got what, when they were gonna get their refills.”

The pills flowed freely for at least a decade starting in the early 2000s, according to Wolf Necklace and several other members of the tribe who spoke with VICE News for our podcast “Painkiller: America’s Fentanyl Crisis.” They said it was normal for tribe members to visit the pharmacy to get prescriptions for powerful opioid painkillers, then swap those pills for alcohol, illicit drugs such as methamphetamine, or cash.

“People really weren't even looking at it like it was a bad thing that they were selling their pills,” said Wolf Necklace. “They were talking about actually how fast they could get rid of them, like within minutes and they would have this extra income.”

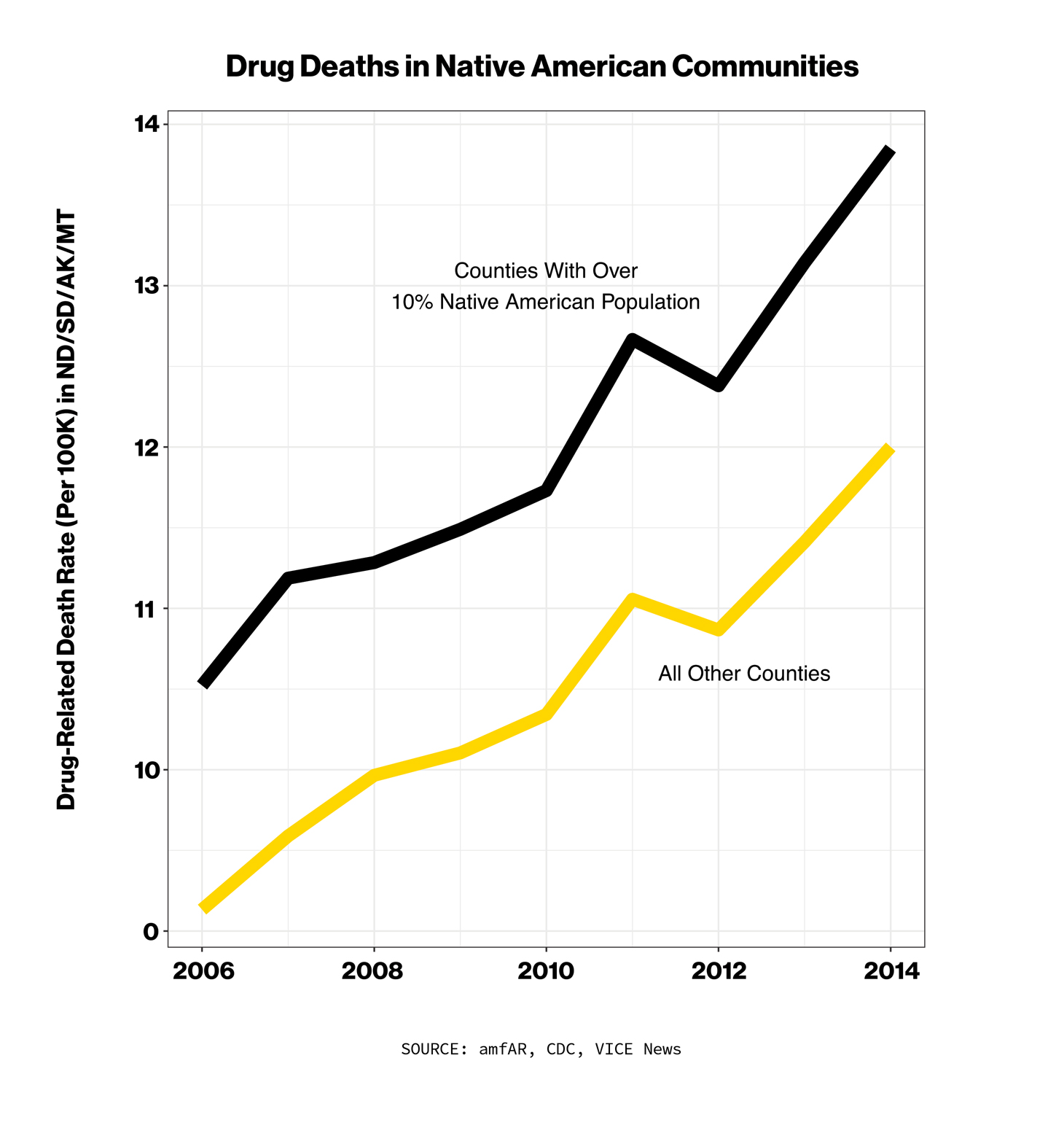

Wolf Necklace eventually found sobriety and now works as a paraprofessional at the local elementary school and as a peer support specialist for the tribe, counseling others struggling with addiction. Like hundreds of other Native American tribes around the country, the Standing Rock Sioux have been devastated by the opioid epidemic over the past two decades. The rate of overdose deaths among Native Americans increased 519% from 1999 to 2015 — more than any other group, according to the CDC, and it remains well above the national average.

The Standing Rock Sioux and other tribes are now fighting back against the drug companies accused of supplying a glut of pills to the reservation.

In 2018, the Standing Rock Sioux filed a class-action lawsuit against more than a dozen companies, including The McKesson Corporation and three other major drug distributors, alleging that they “intentionally flooded the market with opioids and pocketed billions of dollars in the process.” At least 130 other tribes have filed similar claims, along with over 2,000 cities, counties, states, and other entities. All of the cases have been lumped together and are being heard by one federal judge in Ohio. Billions of dollars in settlement money are at stake.

The lawsuits against opioid manufacturers and distributors have revealed the shocking volume of opioids sent to American communities — over 100 billion pills in just one decade, according to a count by the plaintiffs in one lawsuit. Years worth of DEA data on pill shipments is now publicly available, but Native American reservations have been a black hole for such information due to efforts by drug companies to keep the material protected during ongoing litigation. A Washington Post database shows Sioux County, North Dakota, which contains part of the Standing Rock reservation, receiving zero pills per person from 2006 to 2014. The actual number, according to records obtained by VICE News, was 32 pills per person each year.

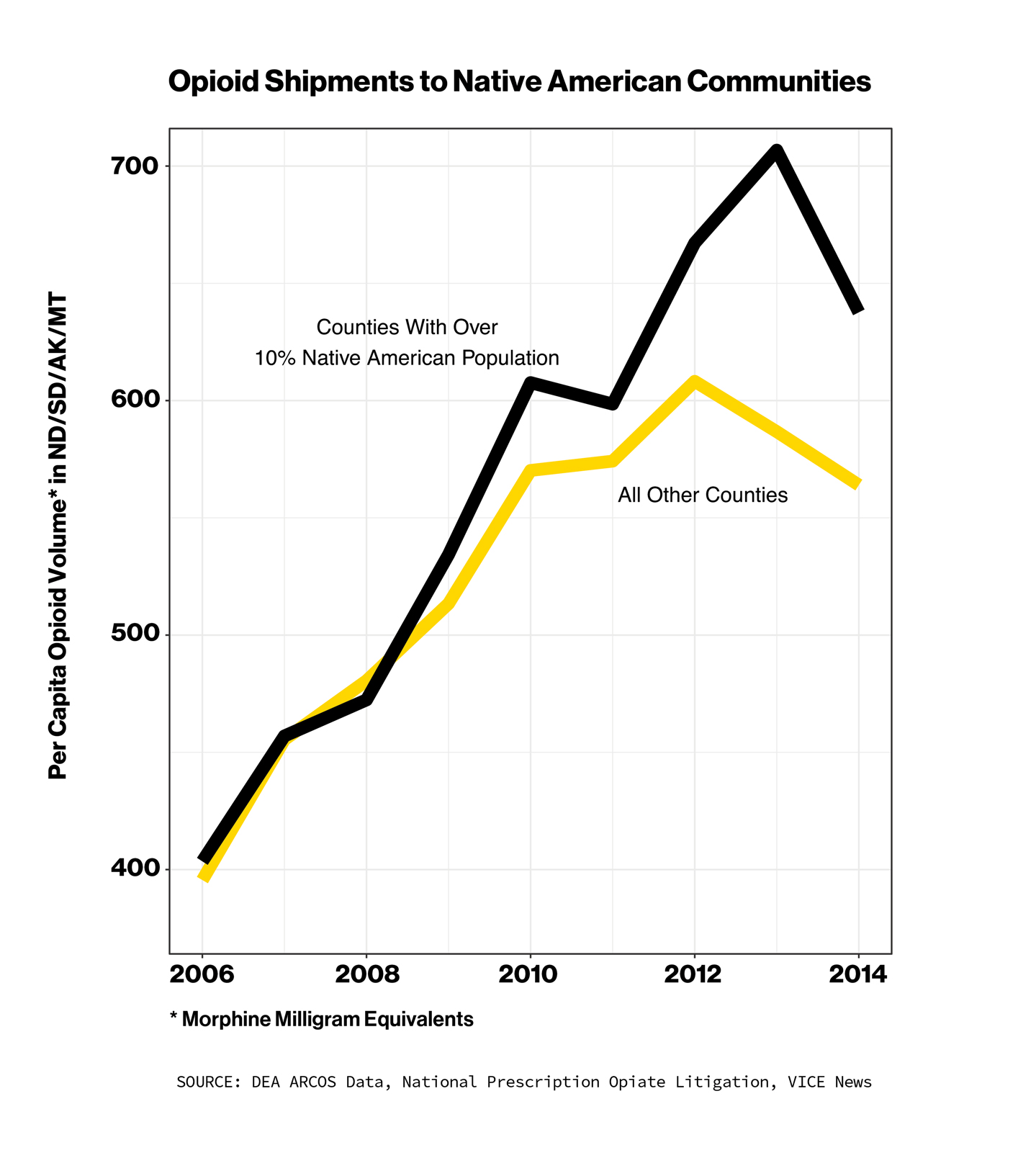

The records show opioid shipments to Standing Rock and other reservations skyrocketed in that period. During those years, the supply of pills per capita doubled at Standing Rock, compared to the national average increase of 30%. One pharmacy just west of the reservation in North Dakota only served a county of around 2,000 people but got shipped enough opioids to rank in the top 15% of pharmacies nationwide based on volume of pills received.

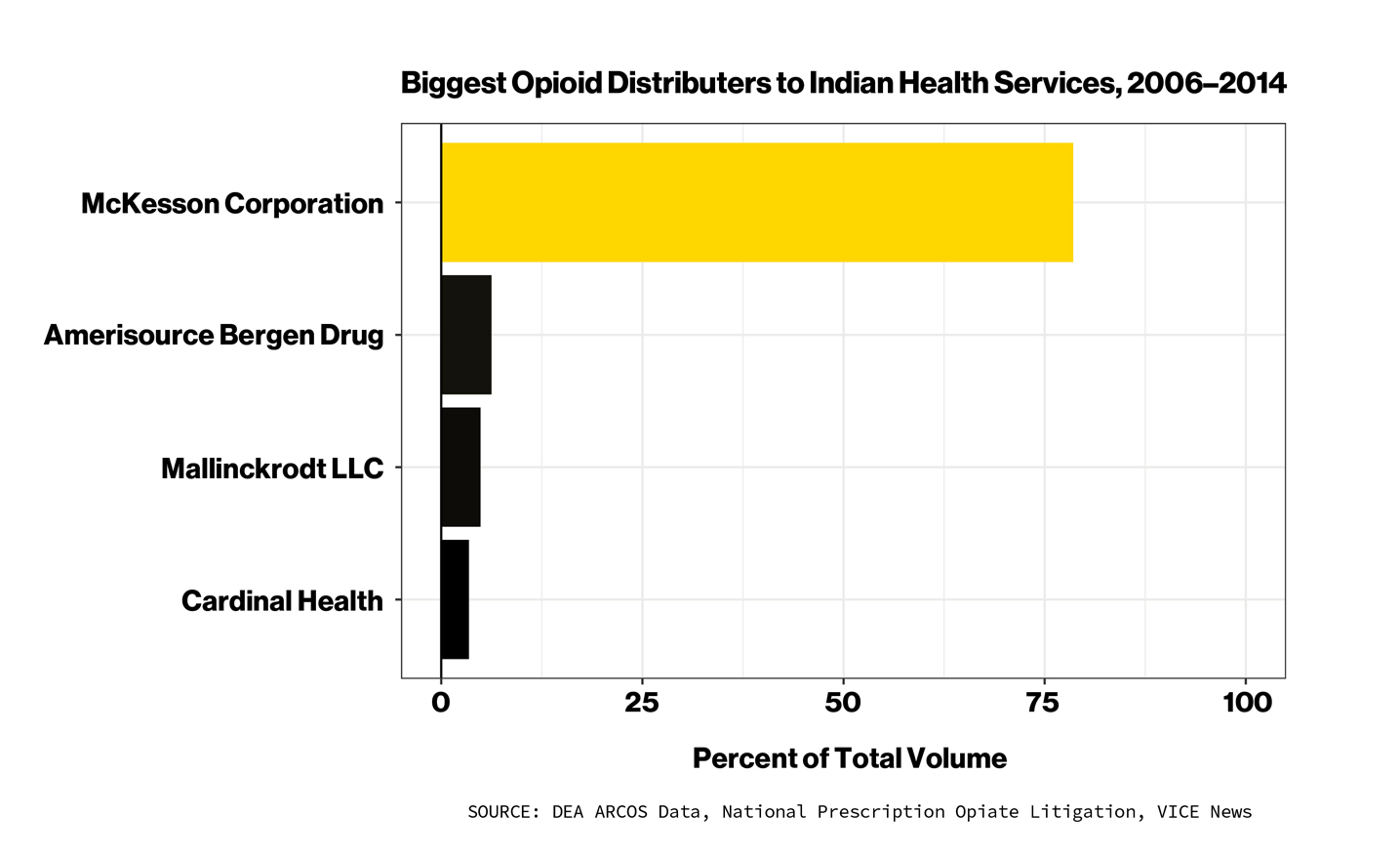

The dataset, sourced from a non-public DEA database that tracks the national distribution of controlled substances, shows that The McKesson Corporation was responsible for supplying the majority of the pills to Standing Rock and other Native American communities. Nationwide, McKesson handled nearly 80% of the opioids shipped to Indian Health Services facilities from 2006-2014 — 10 times more than any other company.

McKesson is a Texas-based health care industry giant that provides a range of services, but its primary business is distributing pain pills and other medications, ensuring the products get from manufacturers to local pharmacies. It’s the biggest of the so-called “Big Three” distributors, along with Cardinal Health and AmerisourceBergen, which collectively account for 90% of all drug distribution business in the U.S.

The distributors are essentially middlemen in the U.S. drug supply chain, but they play an important role. According to Rod Rosenstein, the former deputy attorney general, the DEA uses “a self-reporting model” that relies on McKesson and other distributors to blow the whistle on pharmacies that place suspiciously large orders. But the companies get a cut from each shipment, creating a financial incentive to look the other way. As Rosenstein noted, the distributors have largely escaped punishment for supplying pill mills.

“Clearly, DEA needs to do a better job of overseeing that because no self-regulating system is going to be effective in the absence of enforcement,” Rosenstein said last year in an interview with VICE News. “There has to be some consequence if you don't follow the rules.”

In 2017, McKesson paid a $150 million civil penalty to settle allegations that it failed to report suspicious orders of opioid pills and other medications. That followed a $13.25 million fine for similar issues in 2008, including $544,000 for one case where 824,000 “units” of fentanyl, oxycodone, and other potent painkillers were shipped to a clinic on the Blackfeet reservation in rural Montana. In both instances, McKesson denied wrongdoing when paying the fines. The payouts were relative pittances for the company , which generates more total annual revenue — $214 billion in 2019 — than household names like AT&T, Chevron, and Ford.

McKesson has a “prime vendor” contract to be the main supplier of opioids and other medications to Indian Health Services. In a statement to VICE News, a McKesson spokesperson said the company didn’t have the “discretion to reject orders or second-guess the medical needs of federal facilities.” In a recent, ongoing case involving the Cherokee Nation, a federal judge agreed, ruling that McKesson “could not unilaterally choose to not fill a government order.”

Dr. Donald Warne, a professor and associate dean at University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences who is serving as an expert witness on behalf of one Native American tribe suing McKesson and other opioid distributors, said the large volume of opioids sent to reservations “were really not to treat pain but to promote addiction and make money.”

“It's indefensible to say that it was just fulfilling a federal contract to distribute that many opioid pills to a community that's resulting in overdose and death,” Warne said. “I don't accept that as a defense, and I don't think the legal system will either.”

McKesson has deflected blame to doctors for overprescribing opioids, and to pharmacies for failing to control the supply of pills at the retail level. In the case of Indian Health Services, a federal watchdog issued a scathing report last year that found government-run pharmacies were not following safeguards to prevent patients from filling prescriptions from multiple doctors. In the hospital at Standing Rock, inspectors found the opioid supply stored in an unlocked area. In a written response to the report, IHS said it had since taken steps to improve control of the prescription opioid supply on reservations.

One former pharmaceutical executive has said under oath that drug distributors ignored data that clearly showed suspicious orders. That allegation comes from Michael Babich, the former CEO of Insys, a company that sells the powerful opioid fentanyl in spray form. Babich was sentenced in January to 30 months in federal prison for racketeering after investigators found Insys bribed doctors for prescribing fentanyl.

In a deposition obtained by VICE News, Babich said the major distributors — including McKesson — never raised any alarms about large opioid shipments, even though they had access to real-time data that should have made the questionable orders easy to spot.

Babich said Insys also knew they were supplying pill mills with the company’s fentanyl spray for severe pain treatment. He called the pill-mill doctors “whales” — their biggest clients. He said real-time data allowed his company to see when patients were not refilling their fentanyl prescriptions after starting a trial on a low dose. The company, he explained, would then encourage doctors to start with larger doses that would essentially get people hooked.

“We were able to see that we were suffering a large number of patients that were getting the drug initially and then not coming back for a refill,” Babich said. “And so we were able to then glean the fact that doctors are starting too low of a dose and not getting the patient up to a dose that was effective for them.”

The larger doses, Babich explained, meant more money for both his company and the distributors like McKesson, which charge a percentage for the overall value of each order. Shipping more total milligrams of opioids meant more profits for everyone involved. The distributors, Babich claimed, never raised any concerns about the high volume of fentanyl prescriptions that Insys’ “whales” were writing. McKesson did not respond to a request for comment about Babich’s allegations.

Last October, McKesson and the two other major drug distributors agreed to pay a $215 million settlement with two Ohio counties involved in the same litigation as the Standing Rock tribe and other entities. The “bellwether” cases were handled first as a sort of test run for the courts. McKessson admitted no wrongdoing, and the company’s website states that it is “committed to maintaining — and continuously enhancing — strong programs designed to detect and prevent opioid diversion within the pharmaceutical supply chain.”

The Standing Rock tribe is hoping for a similarly large payout, but it’s unclear when — or even if — that money will come as the cases drag out in court. Meanwhile, opioid addiction is still a major concern on the reservation. The lawsuit says the tribe has seen “child welfare and foster care costs associated with opioid-addicted parents skyrocket,” and “almost every tribal member has been affected.”

Tim Purdon, a former U.S. Attorney in North Dakota who represents the Standing Rock tribe in their litigation, suspects most Americans have no idea how the opioid crisis has devastated Native American families.

“They don't understand the isolation, poverty, and hopelessness that many people can face on reservations in the Great Plains and in the Southwest,” Purdon said. “The lack of access to health care, the lack of access to quality education, the lack of job opportunities. They are forgotten. And it's tragic because their story is America's story.”

The opioid data referenced in this story is available for download here (2006-2010) and here (2011-2014). These files are approximately 1.5 GB each. If you have tips, questions, or would like more information about the data, please contact keegan.hamilton@vice.com.

Jesse Alejandro Cottrell contributed reporting. Collage by Hunter French / Images via Getty.

from VICE https://ift.tt/33b6fJI

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment