It’s time to wake up. On Global Climate Day of Action, VICE Media Group is solely telling stories about our current climate crisis. Click here to meet young climate leaders from around the globe and learn how you can take action.

In Paulatuk, a remote Arctic hamlet in Canada, Inuit Elders remember immense icebergs that once floated along this stretch of the Northwest Passage, the iconic Arctic waterway that links the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

“You never see those anymore,” said one Paulatuk resident at a workshop, part of a series that aimed to document Inuit perspectives on the future of the Northwest Passage. The workshops, held in 2015 and 2016, were organized by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, a nonprofit that protects Inuit rights in Canada.

“The whole aspect of our traditional lifestyle is changing because of the Northwest Passage,” said another workshop participant, this one held in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of Canada, which sits at the western end of the passage. “Open seas, late freezing, early thaw, longer free water season, or free-ice season… It’s going to change everything.”

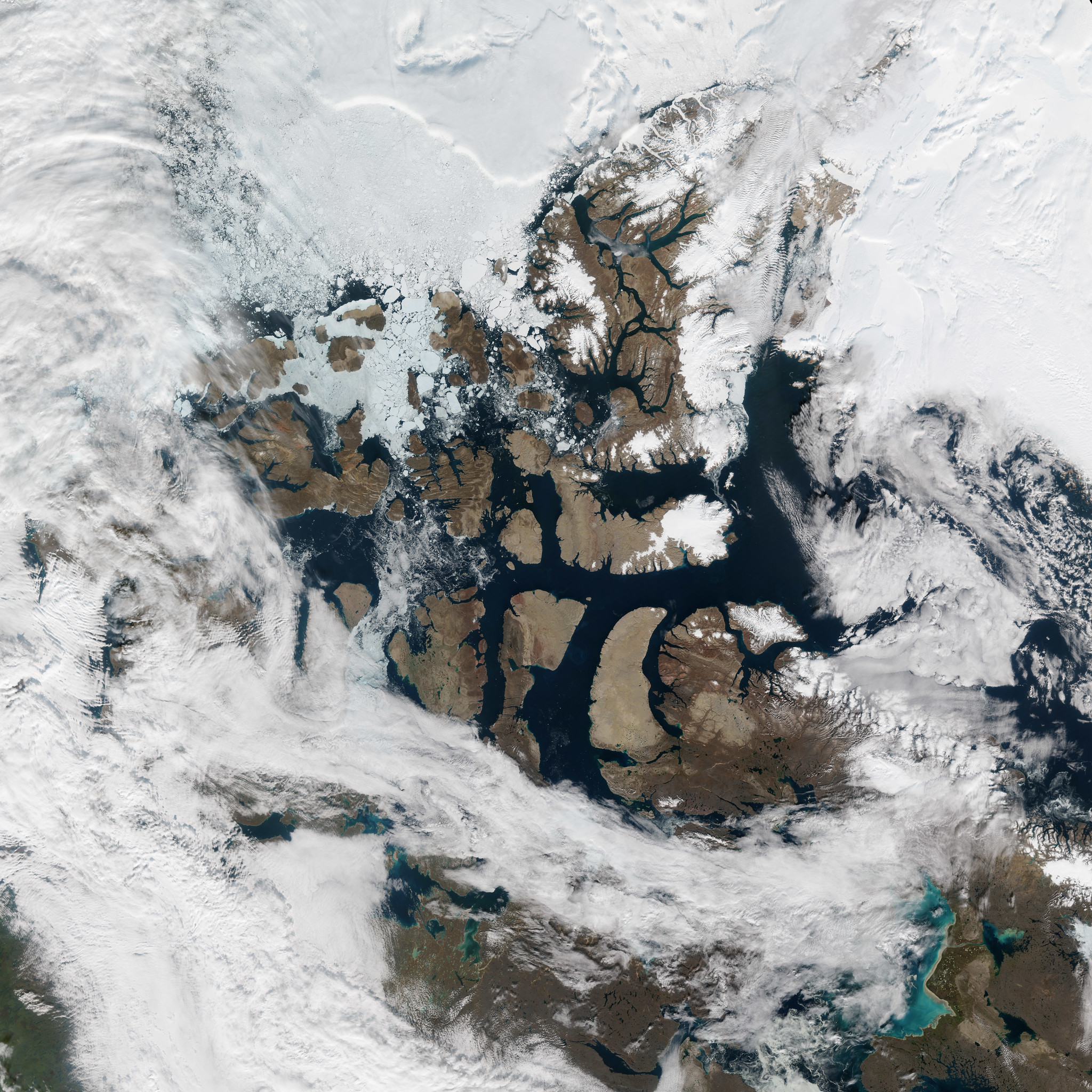

Over the past two centuries, the Northwest Passage, which spans roughly 1,450 kilometers, has earned a reputation to outsiders as intractable and haunted due to the capricious interplay of its ice, snow, and sea. The marine ice pack has proved deadly to many who tried to chart the Northwest Passage—most infamously the doomed Franklin expedition—making it an encumbrance to commerce and colonization.

Now, the passage is becoming busier as warmer temperatures reduce the sea ice, enabling more ships to traverse it. The Arctic, as a whole, is an emerging center of commercial activity and a geopolitical stronghold that is already contested between governments. A wide range of corporate, federal, and military interests are mobilizing to capitalize on the Arctic’s growing accessibility to vessel traffic, heralded by the projected loss of ice cover.

Indigenous peoples of the north are finding themselves at the center of a geopolitical climate change bomb that they did not cause. Attuned to the complex patterns of sea ice for millennia, they are now experiencing dramatic shifts to the natural landscape and the larger marine food web they rely on.

As the people with the most intimate knowledge of these coasts and seascapes, the rights and wishes of Inuit must be the top priority in discussions of the Arctic’s future.

“We know what the law of the sea is,” said Dalee Sambo Dorough, chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, an NGO that represents approximately 180,000 Inuit across four countries.

“Every international legal instrument should have our views and perspectives at the forefront,” she told VICE News from Anchorage, Alaska. “Everything that happens throughout the entire Arctic Ocean and its coastal seas is interconnected, and we know this.”

Arctic communities have experienced the undeniable effects of the climate crisis for decades. The Arctic is warming at nearly twice the rate of the rest of the world on average—and even three times higher in some communities—causing waterways like the Northwest Passage to lose more ice every year.

Average Arctic temperatures are higher than they have been for tens of thousands of years, according to a 2014 study. This trend was most recently emblematized by a record Arctic temperature of 38 C (100.4 F) in Siberia this June, amid devastating wildfires.

“When climate change becomes more progressive (like we have seen over the years), it’s first noticeable in the Arctic, whether that is the Arctic waters, or the land, but Inuit experience this firsthand before anybody else in the world,” Crystal Martin-Lapenskie, president of the National Inuit Youth Council, told VICE News.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) aims to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels, an increase that is all but inevitable at this point. The next best limit is a 2 C rise, which we may hit by 2100 without major reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

“For Inuit, this difference is profound,” said Natan Obed, president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, in a 2019 Macleans op-ed. “The difference between a 1.5 C world and a 2 C world is a sea-ice-free summer every 100 years rather than at least once in 10 years.”

Such rapid changes have profound implications for Inuit lives and livelihoods. The thaw of permafrost, a layer of soil that remains frozen all year, is causing damage to people’s homes that may eventually affect millions of Arctic residents. Coastal erosion and extreme weather events have already forced many Inuit communities to move from their traditional lands to new locations.

Subsistence hunting and fishing sustain many Inuit communities, both as food and income, but warmer temperatures are already disrupting Arctic food webs.

In the Alaskan city of Kotzebue (also known as Qikiqtaġruk), the diminishing presence of thick sea ice has interrupted the marine ecosystem, putting the community’s traditional seal hunts and subsistence diet at risk.

“Last year there were so many people who, because the ice left so fast, they just could not get anything,” Kotzebue resident Lance Kramer told VICE News in July. “We had to go miles and miles to find ice and hunt seals there. And even then, we didn’t get what we needed.”

“Never before has that happened in my lifetime or any of our Elders’ lifetimes,” Kramer said.

Some studies predict that, within decades, it will be common for there to be virtually no summer sea ice covering the Arctic Ocean.

Though some inland communities rely more on land animals such as caribou, most Inuit traditions, livelihoods, and diets are deeply interwoven with marine mammals. Narwhal, beluga whales, bowhead whales, ringed seals, and walrus are not only a source of food, clothes, and tools, but an integral part of Inuit ritual life.

“Traditional activities that are synced up with migratory opportunities become out of sync,” said Alex Whiting, who is not Indigenous but has lived in the Arctic for decades and serves as director of Kotzebue’s environmental program.

“There’s a natural rhythm and pattern to not only fish, wildlife, and bird movements having to do with the winter and summer season, but also a whole slew of traditional gatherings and harvesting activities that are synced up, too,” he told VICE News.

“We are thinking about our new accessibility that translates to increased traffic, increased chances of accidents, and oil spills.”

As the Northwest Passage and other Arctic waterways become more accessible to vessels, increased shipping activity will place even more pressure on these vulnerable ecosystems, and the communities interlinked with them.

“Vessels pose multiple potential risks to Arctic marine mammals” such as ship strikes and noise pollution, Donna Hauser, a marine ecologist at the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska, told VICE News.

Arctic marine mammals are “sentinel species,” Hauser noted, which means they are likely to be the first animals to suffer measurable effects of environmental stressors like climate change. This makes them a kind of harbinger of what’s to come for a region’s overall biodiversity.

An uptick in shipping also presents the possibility of major oil spills or other industrial accidents. This is sadly not a hypothetical for Arctic communities; the Exxon Valdez disaster of 1989 still looms large for Indigenous communities upended by it.

“We are no longer thinking of the Northwest Passage as the route that takes us beyond our communities,” said Nancy Karetak-Lindell, a former Member of Parliament for the Canadian territory of Nunavut.

“We are thinking about our new accessibility that translates to increased traffic, increased chances of accidents, and oil spills.”

In the face of these enormous challenges, Inuit communities are developing creative approaches to mitigate the risks of climate change. The establishment of Tallurutiup Imanga National Marine Conservation Area, which covers 108,000 square kilometers at the eastern entry of the Northwest Passage, is one example.

The area “plays a pivotal role in ensuring that food and resources are protected for those who rely on this,” Martin-Lapenskie said.

Further east, the Inuit-led Pikialasorsuaq Commission aims to conserve the biodiversity of a large stretch of open water between Greenland and Canada.

Besides anticipating the negative effects of shipping in the Northwest Passage, Inuit communities also want to ensure that they can share in the benefits of the increased commercial activity, including tourism.

In another Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami workshop, participants were often enthusiastic about welcoming tourists to their communities, but they also expressed concern that visitors would not reciprocate respect for their culture—by disrupting burial sites, taking artifacts, or trafficking drugs.

“They wanna see all those old, cool sites that our ancestors lived in,” said a workshop participant from Cambridge Bay, Nunavut. “But are they disturbing anything? Are they touching anything? We don’t know.”

Workshop participants from many communities also “worried that people might return home with strong opinions on Inuit culture, and on what people should or should not be doing, particularly regarding issues such as the seal hunt.”

These concerns foreshadow the urgent need to ensure that Inuit interests and Indigenous knowledge remain central to any development of their traditional lands.

“Indigenous knowledge, as some may be aware, is having experienced firsthand what you see, hear, and do over the course of generations by way of survival,” said Martin-Lapenskie. “Inuit have been very open about the different changes in environment, from land to ice thickness, to waterways—these all have changed over many generations and shared through storytelling.”

“We have a right to a seat at the table.”

Martin-Lapenskie is part of a new generation of activists making huge strides in the international movement for climate justice. She joined other Inuit youth leaders in emphasizing the need for food security, infrastructure, and transportation for Arctic communities at last year’s UN Climate Change Conference in Madrid. Their message is also gaining traction through social media, despite spotty broadband connectivity in many Arctic communities.

These approaches have helped boost the signal of the climate crisis in the Arctic. But there is still more work to be done to ensure that escalating activity in the Northwest Passage doesn’t continue to marginalize the region’s Indigenous peoples.

“This discussion about the Northwest Passage, more often than not, is being thought of in the context of commodities, and the removal of commodities from the Arctic for the rest of the world’s enjoyment and use,” Dorough said. “To some extent, the fact that there are people within the region—Inuit—who inhabit the region, doesn’t even cross the radar screen for those who are calculating shipping times and how much fuel they are going to save per day.”

These short-term interests, weighed against the deep cultural history and natural resources of the region, bring back to mind the ill-fated Franklin expedition. Sir John Franklin, along with Terror commander Sir Francis Crozier, were not strangers to the Arctic; they had racked up years of previous experience in the region.

But the Arctic was not their homeland, a reality that is still reflected in the name “the Northwest Passage,” which is Eurocentric both in its navigational orientation and its implication that the waterway is simply a place to pass through.

For more than a century, the most important clues about the last gasps of the expedition were provided by Inuit who interacted with survivors and found remains of the dead. This Indigenous knowledge not only fell on deaf ears back in England, but was viciously rejected in a smear campaign.

This marginalization of Inuit knowledge still stings today, according to young people who attended an Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami workshop in Iqaluit. Some mentioned how Franklin was known as “the finder of the Northwest Passage,” even though “Inuit knew about it” all along. Others talked about how Elders had passed down orally the location of the doomed ships: “They always knew it was there, but I think they’ve been waiting to be asked.”

Since Franklin’s time, the Northwest Passage has been navigated by many nations. The sea ice in the region still imposes dangers to its visitors, but the larger threat is clearly the change imposed on these waterways by the actions of the rest of the world. Few may have visited the Arctic in person, but our collective behavioral fingerprints are all over it.

The thawing of the Northwest Passage is attracting the attention of many international stakeholders. But Inuit are not mere “stakeholders,” Dorough emphasized. They are rights-holders who must keep a long view of the future, especially as others look only to the next financial quarter.

Inuit “have a responsibility to safeguard those resources, to safeguard those lands and territories, not only for here and now, but for centuries to come,” she said. “That’s a huge responsibility, and by virtue of that alone, we have a right to a seat at the table.”

Follow Becky Ferreira on Twitter.

Have a story for Tipping Point? Email TippingPoint@vice.com

from VICE US https://ift.tt/3621zqV

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment