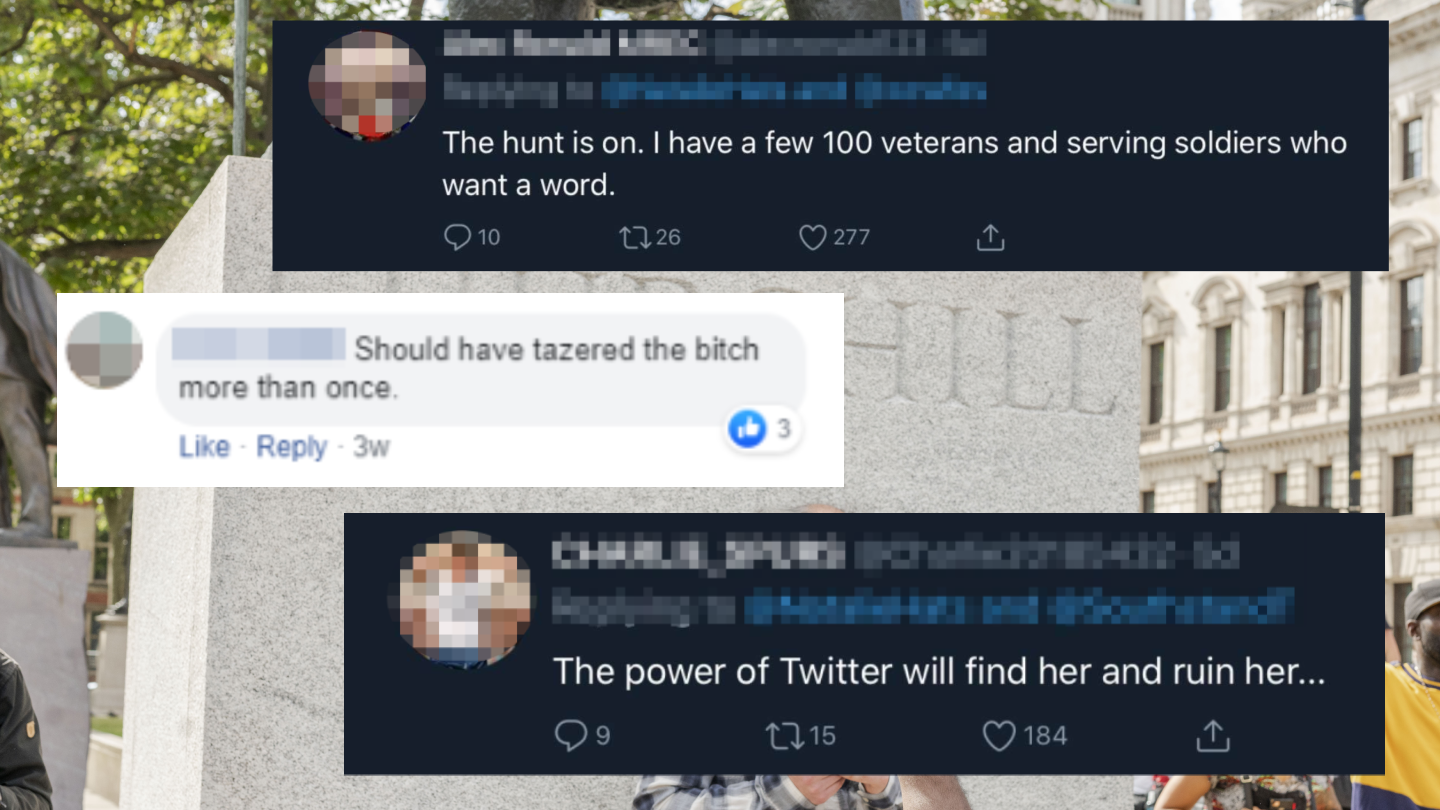

Helen* won’t be wearing earrings on her next protest. She’ll be tying her hair up and keeping her mask on – partly because of coronavirus, and partly because her face has been shared thousands of times online by white supremacist accounts. “This rat defaced the Winston Churchill statue in London,” reads one tweet above a photo of Helen. “Shop the bitch.”

Twenty-one-year-old Helen is one of many people who have attended Black Lives Matter protests and been targeted online with defamatory posts and harassment as a result. On 3rd June, Helen was seated in front of John Boyega as he spoke to the crowd in London’s Hyde Park. “He was keeping his tears back and just talking about the future and how beautiful this country could be,” she recalls. “Days after the march a friend sent me a link on Twitter saying, ‘somebody posted this thing calling you a little shit and saying you spray-painted the Churchill statue.'"

In the eyes of “antifa watch” Facebook groups and those who post enthusiastically about Spitfires, Helen became suspect number one for a vandalism incident on 6th June when she was sat at home in Brighton.

“The comments were like, ‘so we need to find where she lives and we need her arrested,’ and then other people were saying ‘arrested is not good enough. We need her dead’ and someone said, ‘Well, I can help with that. I have 100 veterans on my side. Let's see what she has to say to them,’” she says. “It was really dark and horrible.”

Some Facebook posts about Helen have been shared over 90,000 times and include a photo taken on June 3rd when Helen approached Churchill’s statue with homemade signs. “Winston Churchill set up concentration camps in Kenya and was responsible for the Bengal famine,” says Helen. “So we had like little cardboard signs that we were going to put around him. I mean, that is not vandalism and is simply educating people on his history.” According to Helen, she never even got to place the signs – a police officer was too concerned for her safety.

I first contacted Helen when I saw her defending herself when someone online accused her of criminal damage. I sent her tips from a cybersecurity expert; the Crash Override Network, an advocacy group and resource centre for people experiencing online abuse, and the in-depth advice from the anti-harassment non-profit HeartMob.

To understand what else can be done in Helen’s situation, I spoke with leading barrister Paula Rhone-Adrien. “Firstly, the person affected should immediately contact the social media platform and make it clear that they will be held partly responsible for permitting the continuation of the defamatory material,” she explains. “Alerting the relevant platform to the fact that they could be caught up within any legal melee is enough to send up red flag alerts and should move them into action.

“The victim could also contact the police and inform them that they are suffering intimidation, harassment or even being pestered by the online abuse and that the person and any other person responsible for sending the offensive image could face criminal prosecution. Alternatively, the victim could seek a civil injunction prohibiting the further dissemination of the defamatory comments and damages against any person who continues to do so if they fail to heed the warning.”

Rightwing media personality Katie Hopkins learned this the hard way when her tweets implied that food writer Jack Monroe approved of vandalizing a war memorial during a protest. Losing the subsequent libel case saddled Hopkins with legal costs beyond £300,000.

Unlike Monroe, Helen hasn’t been named in any posts, but Keystone Law consultant solicitor Gerard Cukier points out that “if someone's face is shown, even if their name is not given, and they can be easily recognised, then claims in defamation or harassment can be pursued”.

Some posts about Helen have been deleted since VICE News flagged them with Twitter and Facebook. Twitter told us: “Abuse and harassment have no place on our service and we have policies in place – that apply to everyone, everywhere – that address abuse and harassment, violent threats, hateful conduct, coordinated activity and other forms of platform manipulation. If we identify accounts that violate any of these rules, we’ll take swift enforcement action.”

Facebook confirms that it took down a post relating to Helen: “We don’t tolerate abuse, bullying or harassment on our platforms and we encourage those affected by this behaviour to report it so we can take action.”

Helen has contacted the police about the death threats, but other Facebook posts are still up. Not every activist may feel comfortable with getting in touch with the cops, but similar cases show potential for wider change.

When 23-year-old Momo* was falsely accused of burning a Union Jack flag on a Black Lives Matter protest, the harassment came from publicly elected officials, too. Rushmoor Borough Council has confirmed that a number of complaints were received after Conservative councillor Jacqui Vosper tweeted her own accusation against Momo before deleting her account.

Vosper is one of several Tory councillors recently investigated or suspended, including Colin McGavigan, who compared taking the knee to Nazi salutes, and Robin Vickery who shared a post calling for Black and Asian people to be deported.

Outcomes like this are dependent on a council’s rules and whether a councillor’s political party steps in. When a complaint is raised, councils encourage the public to explain how a councillor has violated its code of conduct – a set of rules required by all councils that set the standards expected from councillors. But each council has its own steps for handling a violation, and while all codes of conduct have to stick to some key principles, there’s a real pecking order when it comes to any mention of social media and harassment.

Vickery’s former employers Suffolk County Council, for instance, has a Code of Conduct that covers bullying and the Equality Act, but there is no mention of either in the code for Rushmoor Borough Council, where Vosper works.

In 2019, the Local Government Association (LGA) found “considerable variation in the length, quality and clarity of codes of conduct” that “fail to address adequately important areas of behaviour such as social media use and bullying and harassment”. It is now carrying out a consultation on a new model code of conduct with a heavy emphasis on online communication.

Rushmoor Borough Council told VICE News that it will engage with councillors on this consultation before it can “adopt a modern code that reflects current issues”, and says that its councillors have agreed to an all-party review of the council’s processes, policies and organisational attitudes toward racism. A source familiar with the matter told VICE News that Vosper offered a personal apology to Momo.

Whether it’s an elected official or your cousin on Facebook, everyone needs to look at how susceptible they are to sharing fake news and the prejudices that encourage that behaviour.

Helen says she’s seen the worst and best of people online. After her image went viral, the 8,000-strong Facebook group Brighton Girl helped report a post with more than 100,000 shares. “I literally had like 200 comments of all these girls saying, ‘don't worry about it, we're blocking him now and we're reporting it to whoever he works for,’” says Helen. “I think that really helped to take it down.

“On the one side, you have such horrible things online and on the other side you have these beautiful girls coming together who had my back. So it gave me so much hope for the future and just reminded me there's so many good people out there as well.”

* Name has been changed

from VICE https://ift.tt/3h8GihF

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment