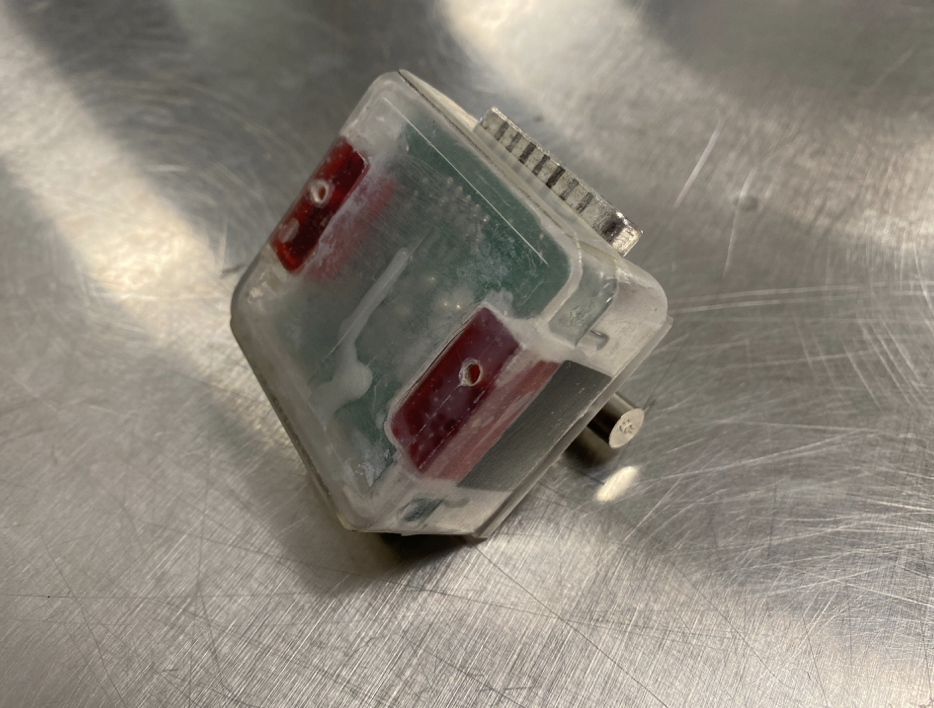

The dongle is handmade, little more than a circuit board encased in plastic with two connectors. One side goes to a ventilator’s patient monitor, another goes to the breath delivery unit. A third cable connects to a computer.

“It’s a little box that goes in between the monitor and the breath delivery unit,” William, a ventilator refurbisher told me. “It’s made custom. The case is an old clock case.”

This little dongle—shipped to him by a hacker in Poland—has helped William repair at least 70 broken Puritan Bennett 840 ventilators that he’s bought on eBay and from other secondhand websites. He has sold these refurbished ventilators to hospitals and governments throughout the United States, to help them handle an influx of COVID-19 patients. Motherboard agreed to speak to William anonymously because he was not authorized by his company to talk to the media, but Motherboard verified the specifics of his story with photos and other biomedical technicians.

William is essentially Frankensteining together two broken machines to make one functioning machine. Some of the most common repairs he does on the PB840, made by a company called Medtronic, is replacing broken monitors with new ones. The issue is that, like so many other electronics, medical equipment, including ventilators, increasingly has software that prevents “unauthorized” people from repairing or refurbishing broken devices, and Medtronic will not help him fix them.

In the case of the PB840, a ventilator popularized about 20 years ago and in use ever since, a functional monitor swapped from a machine with a broken breathing unit to one with a broken monitor but a functioning breathing unit won’t work if the software isn’t synced. And so William uses the homemade dongle and Medtronic software shared with him by the Polish hacker to sync everything and repair the ventilator. Medtronic makes a similar dongle, but doesn’t sell it to the general public or independent repair professionals. It’s only available to people authorized by the company to do repairs.

“This is a copy of a proprietary tool,” William said. “It doesn’t take rocket science to put these things back together. The weak point of these companies’ supply chains is other countries, so through our friends in other countries we’re able to get this stuff.”

The Polish hacker told Motherboard that technicians will take a manufacturer’s repair class in the United States, get the required software, then share it widely through Europe. “It’s officially prohibited to share the software,” they said, speaking of the PB840 software. “But if you know someone, you can just copy it and they cannot track it.”

This grey-market, international supply chain is essentially identical to one used by farmers to repair John Deere tractors without the company’s authorization and has emerged because of the same need to fix a device without a manufacturer's permission. In 2017, Motherboard reported on farmers who are pirating John Deere’s Service Advisor software that’s been cracked by Ukrainians and distributed on torrent sites and forums. They use specialized, aftermarket dongles like the one William described to push the software from a laptop to the tractor itself.

This trade isn’t uncommon among refurbishers and trained repair professionals who work on ventilators and other medical equipment in hospitals. Ryan Zamudio, a military veteran who owns Veritas Biomedical, a company that repairs ventilators in rural California, said that while he and his staff are authorized to work on some manufacturers’ ventilators, he has to turn to internet forums, word-of-mouth trading, or hope he gets a friendly person on the phone at a manufacturer to get software or a repair manual in order to be able to work on others.

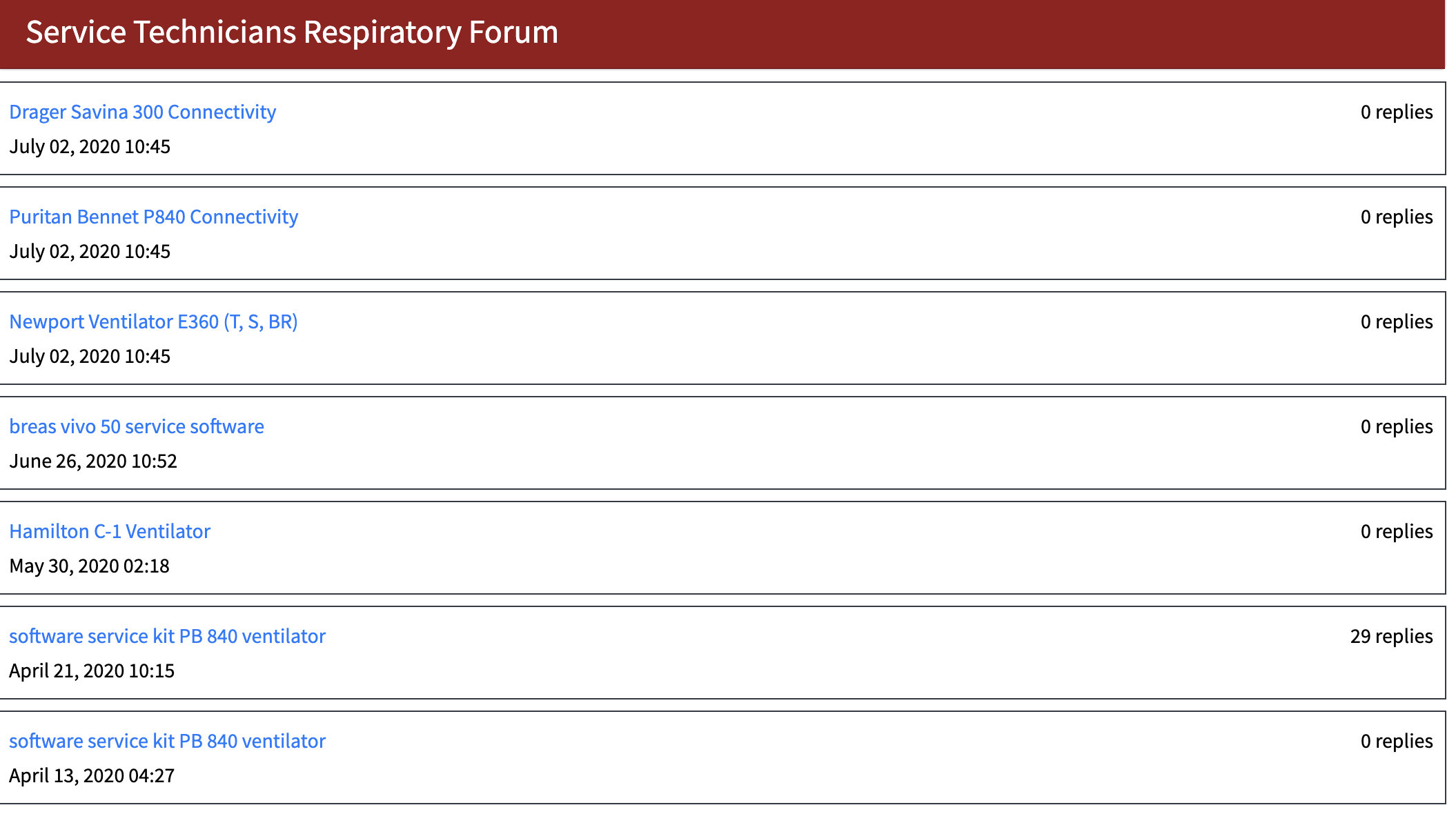

“Service technicians are a community of their own. Sometimes you’ll call someone who works for a manufacturer and they sort of know what you’re facing, so they’ll send you a manual or a link to download the software. They’ll say ‘officially this never happened, and you didn’t get this from me,'” he said. Biomedical technicians also trade software among friends they meet through biomedical society trade groups and forums such as TechNation, 24x7 Magazine and DOTMed. In recent weeks, iFixit has also compiled a huge compendium of repair manuals for ventilators.

While software can be copied and traded and hardware dongles can be used on older devices like the PB840, newer medical devices have more advanced anti-repair technologies built into them. Newer ventilators connect to proprietary servers owned by manufacturers to verify that the person accessing it is authorized by the company to do so.

“You pay between $10,000 and $15,000 to gain access for one year,” the hacker said. “They’re called ‘smart’ machines, but it’s not smart for me, it’s smart for the manufacturer because you spend this enormous amount of money [to repair them].”

*

Faced with a global pandemic, hospitals, biomedical technicians, right to repair activists, and refurbishers like William say that medical device manufacturers are profiteering by putting up artificial barriers to repair that drive up the cost of medical care in the United States and puts patient lives in danger. They describe difficulty getting parts and software, delays in getting service from "authorized" technicians, and a general sense of frustration as few manufacturers appear ready to loosen their repair restrictions during the COVID-19 crisis.

For the past decade, medical device manufacturers have refused to sell replacement parts and software to hospitals and repair professionals unless they pay thousands of dollars annually to become “authorized” to work on machines. The medical device industry has lobbied against legislation that would make it easier to repair their machines, refused to release repair manuals, and used copyright law to threaten those who have made repair manuals available to the public.

The technicians who are unable to gain access to repair parts, manuals, and software are not random people who are deciding on a whim to try to fix complex medical equipment that is going to be used on sick patients. Hospitals and trained professionals are regularly unable to fix the equipment that they own unless they pay for expensive service contracts or annual trainings from manufacturers.

While hospitals deal with a resurgent coronavirus that is overtaxing intensive care units across the country, their biomedical technicians are wasting time on the phone and in Kafkaesque email exchanges with medical device manufacturers, pleading for spare parts, passwords to unlock diagnostic modes, or ventilator repair manuals.

"For a lot of vendors, you have to get recertified every other year to keep working on their equipment. I had a biomedical technician who lost their certification during the middle of the pandemic [because it lapsed]," a source who manages biomedical technicians at 14 different hospitals in a state hit hard by COVID-19 said. "We called the manufacturer and they would not give us the information to service their ventilators. Eventually we get on a call and say 'this is ludicrous, this person has been working on these ventilators for 12 years. Release the service key so I can get patients back on ventilators.'" Motherboard granted the source anonymity because they were not authorized by their company to speak to the press.

A report released Wednesday by the U.S. PIRG Education Fund, a consumers rights group pushing for right to repair legislation that would make restrictive repair practices illegal, found that, of 222 biomedical professionals they surveyed, 92 percent had been denied access to repair information by manufacturers. Many others said that they have broken ventilators in their hospital that they are unable to fix because they “lack access to parts and service information.”

Manufacturers have argued time and time again that they would be liable if one of their machines, repaired by an unauthorized third party, malfunctioned and hurt a patient. In a statement, Medtronic said that the PB840 and machines like it “contain more than 1,500 components and significant complex software code. They rely on a skilled and specialized workforce that adheres to stringent regulatory and safety guidelines for service. Simply providing tools and service manuals is insufficient to understanding how they work and ensuring they are properly repaired. Proper training is also essential to the performance of servicing activities. Training is an extensive and ongoing process and given the complexity of many medical devices, a high level of training is necessary and needs constant updating to reflect knowledge of the latest technology advancements … Ventilator manufacturing is a complex process that relies on a skilled and specialized workforce, an interconnected global supply chain, and a rigorous regulatory regime to ensure patient safety.”

However, hospitals say that they are the ones who will be held liable if their machines malfunction on a patient, and say that their biomedical technicians are more than capable of repairing ventilators. The source who managed biomedical technicians at 14 hospitals said that “we own the risk if equipment fails and someone sues. Never have I heard of an example where the maker of the equipment is named in a lawsuit.”

In a 2018 report, the FDA said that third-party repair professionals “provide high quality, safe, and effective servicing of medical devices.” Quite simply, there are not enough manufacturer-authorized technicians to service equipment during a global pandemic.

"We called a manufacturer to fix a vent and they were 2-3 weeks behind, and that’s before we had COVID-19. With COVID-19 out there, they’re so overwhelmed."

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the biomedical technician manager said that some manufacturers’ authorized repair professionals have refused to come to hospitals to do preventative maintenance on medical equipment and non-urgent repairs; two emails viewed by Motherboard confirmed that Varian Medical Systems, which makes radiation oncology equipment and Arkray, which makes diabetes care devices, would not do certain preventative maintenance or lower-priority repairs on their machines in March, during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I have vendors that only have three technicians for the U.S.,” they said. “I could have someone in house fix something in an incredibly quick turnaround time,” if they had access to parts and manuals. But with some companies, “now they’re flying all over the country and we might have something scheduled for two weeks from now, and you just hope to god there’s not something more urgent that comes up. It’s truly dependent on the vendor. Some have really robust service personnel, others, you never know.”

Bill Bassuk, owner of CER Technology, which repairs medical equipment in Texas and CEO of the College of Biomedical Equipment Technology, which trains students on how to repair medical equipment, said that some manufacturers haven’t been able to keep up with the number of service calls that they’re getting during the pandemic.

“They cannot keep up,” he said. “We called a manufacturer to fix a vent and they were 2-3 weeks behind, and that’s before we had COVID-19. With COVID-19 out there, they’re so overwhelmed.”

J. Scot Mackeil, a senior biomedical electronics technologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, who was named “biomedical technician of the year” by a medical device manufacturers trade group in 2018, said that his hospital regularly can’t get the parts or documentation needed to fix devices they nominally own. Mackeil has spent time over the last few months vetting emergency stockpiles of ventilators for FEMA.

“It’s a common occurrence for anyone working in my profession to call up a manufacturer and say ‘Hey, I have this device that was presented to me by a caregiver who thinks it’s broken and I have to check it, screen it. Can you provide me with manuals and parts to do so?’ and the company says ’No, we won’t let you work on the equipment,’” Mackeil said. “Well if the hospital bought and paid for it, how is this ‘your’ equipment?”

Mackeil and groups like iFixit and US PIRG say the solution is right to repair legislation. Bills have been proposed in more than 20 states that would require manufacturers to release repair information and sell repair parts to the public. It would also prevent them from putting artificial software locks on their hardware that prevents repairs. Medical device manufacturers and their trade groups—as well as companies like Apple and John Deere—have lobbied hard against this legislation nationwide.

“There is a strong financial incentive for manufacturers to restrict repair. They want to get hospitals to buy repair service contracts from the manufacturer,” Nathan Proctor, US PIRG's Right to Repair Campaign Director said in his group's report. “Manufacturers typically charge much more for repairs than if the hospitals hire a third party or train their own technicians—but more costs aren’t the only price of proprietary repair. Delays in getting equipment running put patients at risk.”

In the meantime, biomedical technicians will continue to try to make-do with what they can. “If someone has a ventilator and the technology to [update the software], more power to them,” Mackeil said. “Some might say you’re violating copyright, but if you own the machine, who’s to say they couldn’t or they shouldn’t?”

“Any good biomed is someone who uses all resources to get the job done,” Zamudio said, “while still complying with regulations and making sure people are safe.”

from VICE https://ift.tt/2ZdcYjZ

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment