The breakout success of Among Us is surprising when you recall that this multiplayer game of find-the-impostor from developer Innersloth was originally released to neither acclaim nor fanfare back in June 2018, and was barely able to scrape together enough simultaneous players to fill more than a couple of games over its first few months of life.

But it turns out that Among Us was just two years early. It was the game of 2020, it just needed reality to catch up to it.

Throughout the past spring and summer A_mong Us_ has been collecting players at an ever increasing rate, and it now boasts more than 85,000,000 mobile downloads and hundreds of thousands of people playing at a time during peak hours. The once-empty servers are so busy it can sometimes be hard to host a game. More importantly, though, it has insinuated itself into the culture of popular gaming, with high-profile streamers and YouTubers racking up millions of views off of their videos for the game.

But why? Why this game and why this moment?

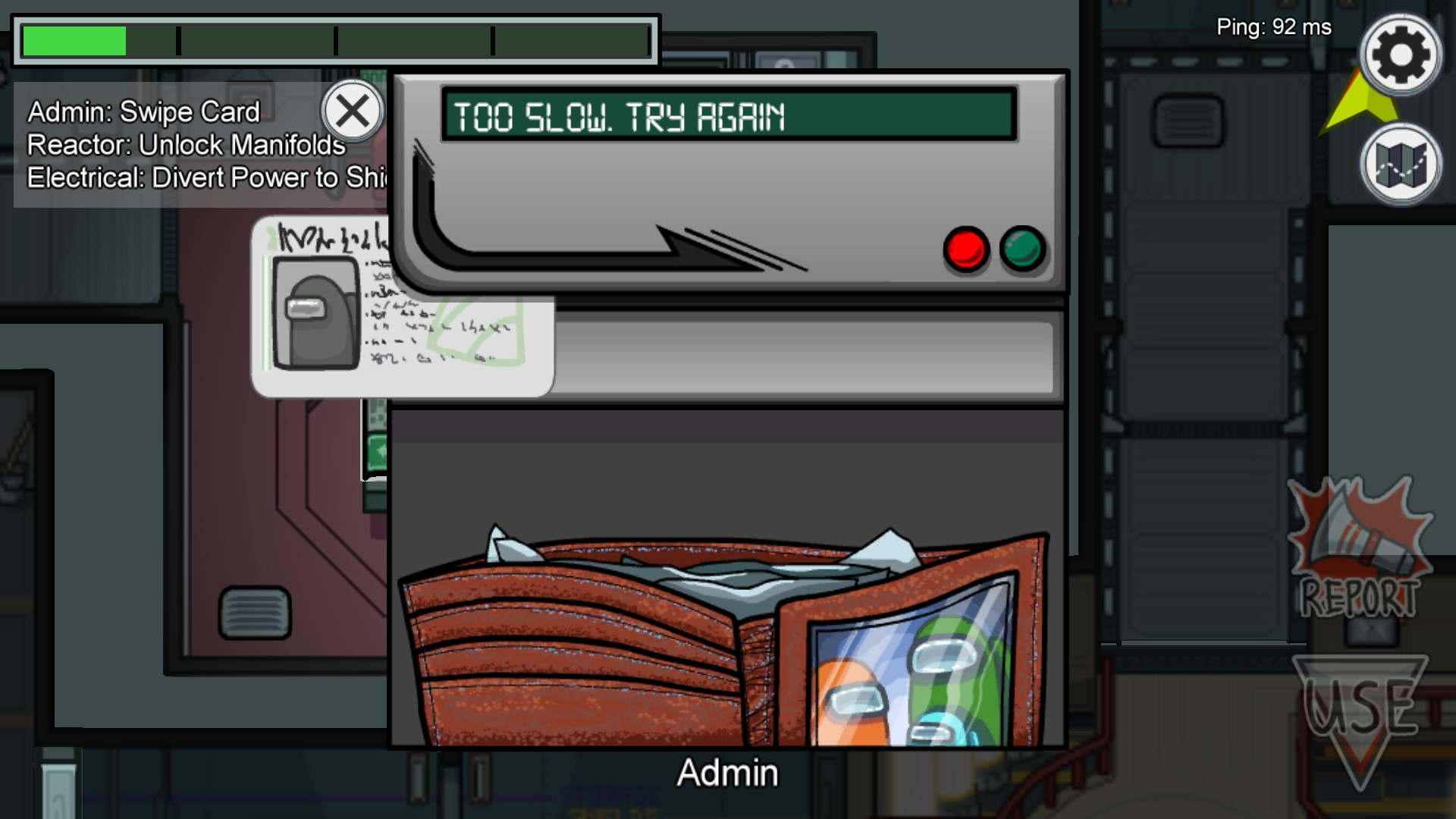

Among Us is simple. In it most players are working cooperatively and are, generally, ‘good’, at least in the sense that they are running around completing a task list designed to allow the whole group to survive and not plotting to murder everyone. Among the good players, however, will be impostors whose job is to kill off the crew before they can succeed in their tasks. At its heart, Among Us attempts to recreate a cinematic kind of tension you might expect in the Antarctic Outpost #31 of The Thing or aboard the Nostromo in Alien, only with a colorful palette and an almost maniacal sense of whimsy cast over the whole thing.

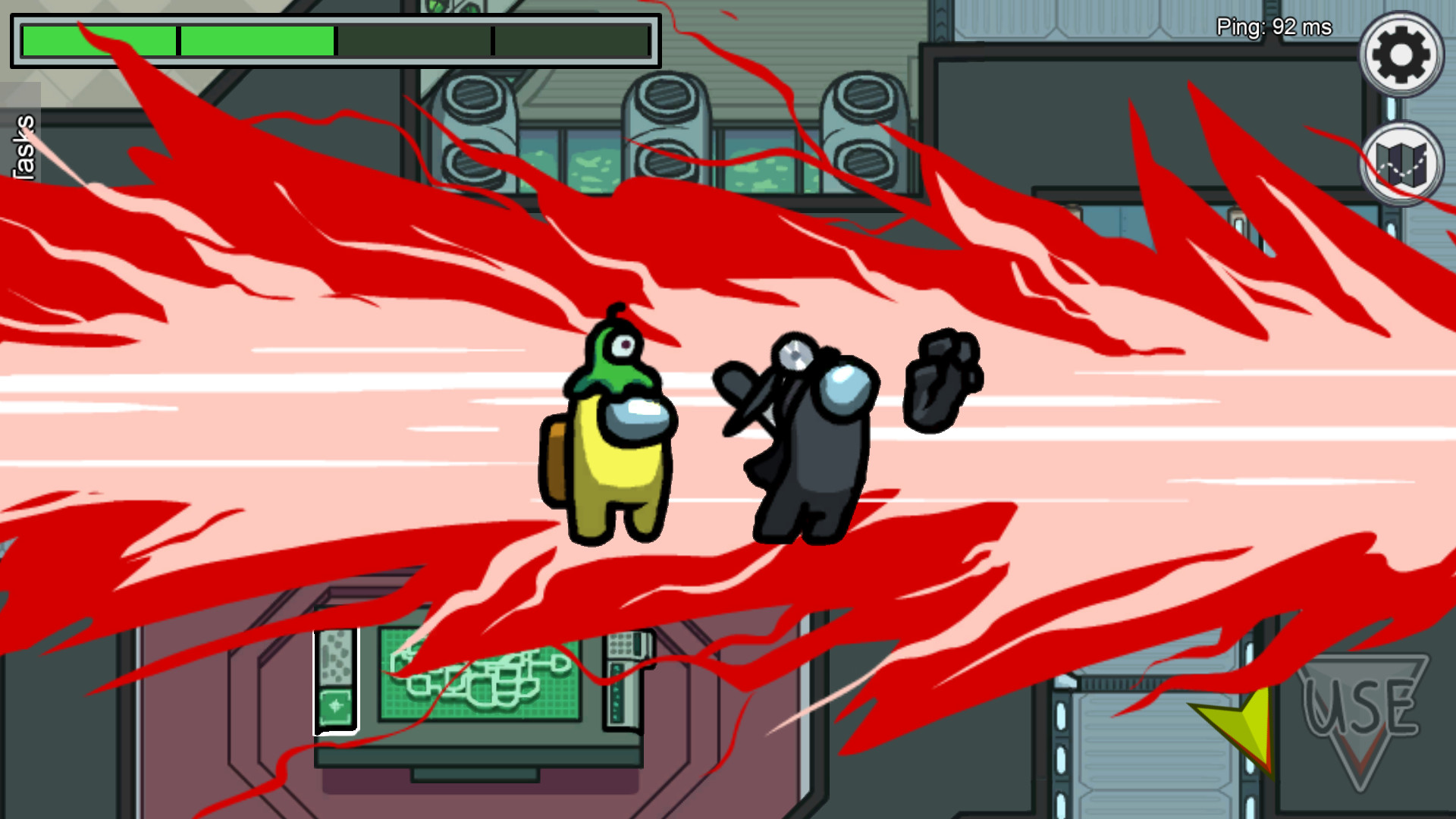

Aside from the fairly obvious movie comparisons, something in this game resonates at the same frequency as the practical experience of being alive in the year 2020. Among Us is rife with ever cascading crises, and people trapped in a sense of isolation while they try to solve problems for which they are woefully unequipped. Into this crumbling world the game introduces a dash of bad-faith actors whose purpose as much as open violence is to sow distrust and distraction. Even after you die in the game, you’ve still got work to do as a ghost, staving off seemingly inevitable failure, which is, itself, a whole separate metaphor begging for examination.

Here in the real world it sometimes feels like every other day holds some new omen that would have once seemed monumental enough for months or years of attention, but now seems like just another day at the nightmare store. So, when the claxons blare in Among Us to tell players that the oxygen has been sabotaged and everyone is about to asphyxiate to death, I feel a kinship with the player who looks around resigned and seems to think, “eh, Red’s probably got this.”

When it comes right down to it, most of Among Us is just a bunch of people trying to get their work done without dying, and that is a sentiment I understand in my bones. I feel connected to these probably-doomed meeples everytime I log into a Zoom meeting for a “capital portfolio review” while the world, quite literally, burns.

So, when some blue player is standing there waiting for a file to upload so they can check another task off the list, all the while expecting someone to wander in and stab them to death, that feels like an essential 2020 kind of emotion.

It’s the almost mundane way that Among Us sets its stage that feels prescient of this vaguely exhausting future we all seem to be trapped in. You are locked in a crumbling environment that forbids organized cooperation with at least one traitor who can and will kill you when the moment is right, but in the meantime can you just sweep up some leaves and empty the garbage? Here in 2020 we call that feeling, “Thursday.”

But all this would not fully capture the zeitgeist if Among Us did not take it one important step further. This isn’t a game just about the doomed resignation of a marginalized and harassed working class. It is a game about communication, and how to abuse it to your advantage.

The most important part of Among Us doesn’t happen in the confines of some spaceship or volcano-base. It happens in the meeting room, a static screen that shows who has died and who is left, because this is the only place where you are actually allowed to talk to other players. And, most importantly, point fingers at them for hanging out too close to a vent or cast doubt about some very suspicious shuffling they did while you were in comms.

It works like this: if someone comes across a dead body as they drudge through their list of tasks, they can report the crime. In addition once per game, by default, each player can call an emergency meeting. In both cases, the entire group is called together to talk it out while a timer counts down the few seconds that everyone has to come to any kind of consensus. Suddenly this once quiet game is alight with a cacophony of accusations, recriminations, alibis and pleading as each player makes the case for why they are innocent or why another player should be thrown out of an airlock.

Half the time, as the shouting and protestations grow in intensity, I start to long for the nice quiet of uploading data while a killer stalks me in the dark.

It is a case study in how the fabrication of chaos destroys communities. Often the traitor doesn’t need full-throated assertions of their innocence, but rather simply to build a plausible scapegoat or cast distrust on the right accuser. The path to victory as often as not for the impostor is to realize how many things everyone is trying to keep track of and capitalize on faulty or uncertain memories. When green suddenly can’t remember exactly what tasks she has left, accuse her of being a traitor. When yellow keeps telling the same (true) story over and over again about how you killed a man in the electrical room, twist that persistent certainty into evidence of deception. It is often just as likely that the person who walks in on the murder scene is going to get tossed in the volcano as the little teal man with a bloody knife in his hands. It’s like the old saying goes, snitches get liquified in molten rock.

Death is no freedom in Among Us, though. Often the hardest part is what comes after your crewmates turn on you. It is the sitting quietly listening in on the follow up conversations, like a judgmental ghost, watching as the traitor who killed you weaves a transparent spell on everyone else, and seeing the same pattern take shape on some new poor bastard. That is a moment that I feel every morning when I see what new fabrication is being propagandized in the morning news, or what new political joke is being played on the world.

This all probably makes Among Us sound like a dour, joyless exercise, but it’s not. Its presentation belies its darker theme, and it is an entertaining implementation of an age-old core idea of having fun while screwing your friends over. At some point the game ends, someone wins, someone else loses and most of the time —not always, but most of the time–everyone goes back to being friends again. This decompression stage in between games as players gather back in the lobby is essential as an outlet for either congratulating well crafted deceptions or bemoaning strategic blunders. A few laughs, a little bit of resentment and ultimately a reconciliation back to the mean usually puts everything right.

That reassertion of the baseline may be the least 2020 part of the game. Among Us is steeped in the ratcheting of tension and sense of impending doom, even for the impostor who can see all those bothersome humans steadily making progress away from their well crafted doomsday. But, the tension of Among Us is finite, and it eventually relents. It grows, it resolves and then it releases you. The release, that’s the part I can’t really identify with right now. Maybe someday, but the in-between while the pendulum resets instead of swinging perilously closer with each arching stroke feels like a nice dream I remember once having.

Maybe that’s the most important reason that Among Us is successful right now. This doesn’t feel like a time most people would probably want to have reflected back to them. Yet, here is a game that feels like it has so many parallels to this moment, save this one final resolution. And, that part is perhaps what we’re seeking more than anything. The feeling of going through the nightmare and waking on the other end. This idea that maybe, just maybe after the chaos has resolved we can get back to something that feels like home.

On the other hand, maybe getting back to a place where we all sit back and laugh about the time we almost threw some people out an airlock shouldn’t necessarily be the goal. I don’t know. All I know is I’ve got these shields to prime and an engine reactor meltdown to stop, and I’m pretty sure that guy over there just tried to kill me. I’m busy. You figure it out.

from VICE US https://ift.tt/3hRCVvf

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment