These days, Hong Kong’s unique cultural identity as a collision of East and West is under threat. The city’s iconic neon glow is dwindling. Colonial heritage sites are being demolished. Schools are replacing Cantonese with Mandarin. In the wake of the 2019 anti-extradition bill protests and subsequent passage of the National Security Law, which effectively criminalizes espousing a pro-Hong Kong identity separate from China, citizens have floated ideas about rebuilding Hong Kong as an independent city-state elsewhere, from Wales or Northern Ireland to Darwin, Australia. But what if the new “Hong Kong” was not confined to a singular geographical location; instead, existing virtually?

As Hong Kong’s history, art, language, traditions, and collective memory are under systematic attack, there is a global grassroots effort to digitize the city’s ephemeral and intangible local culture. Crowd-sourced community archives with family photos, personal diaries, and even old maps of colonial Hong Kong have existed for years. But there has been a strong interest in the preservation of recent history—namely the 2014 Umbrella and the 2019 anti-extradition movements that many say have redefined the Hong Kong spirit.

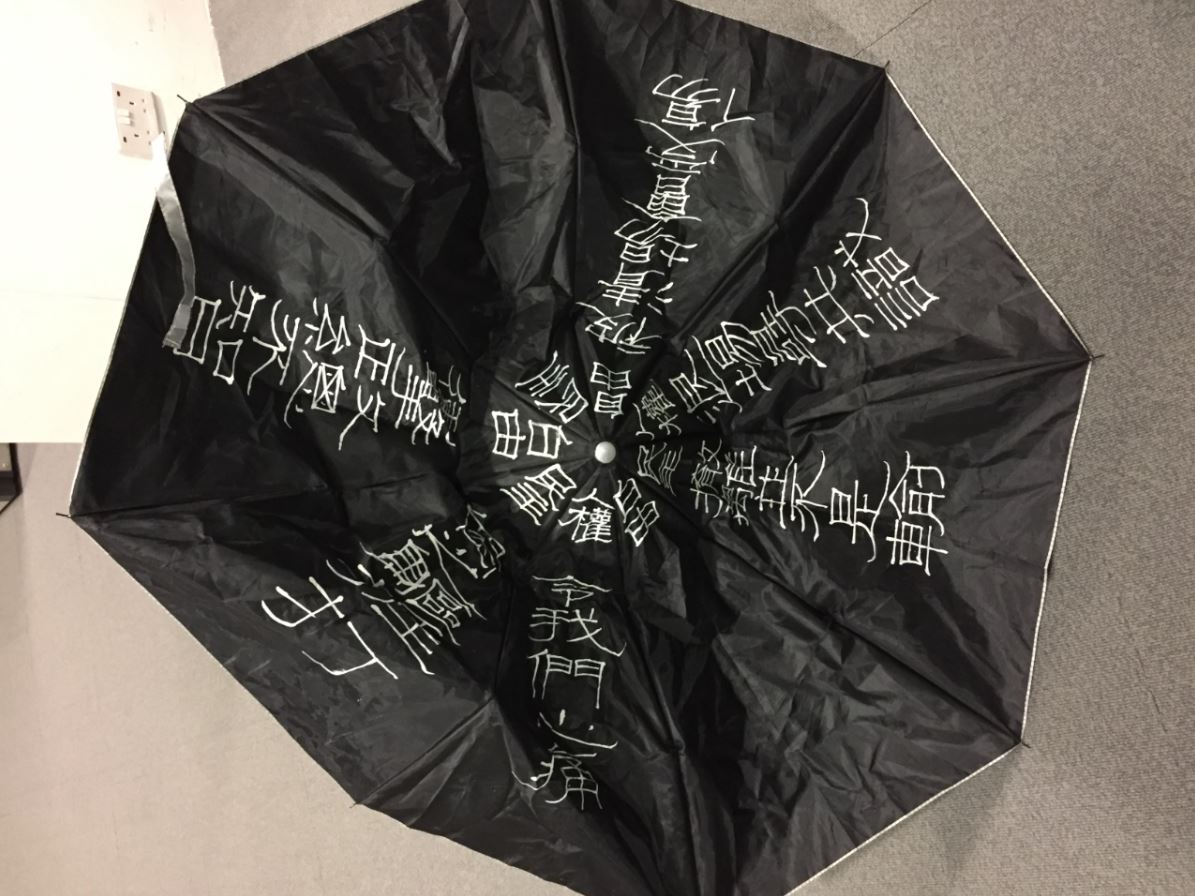

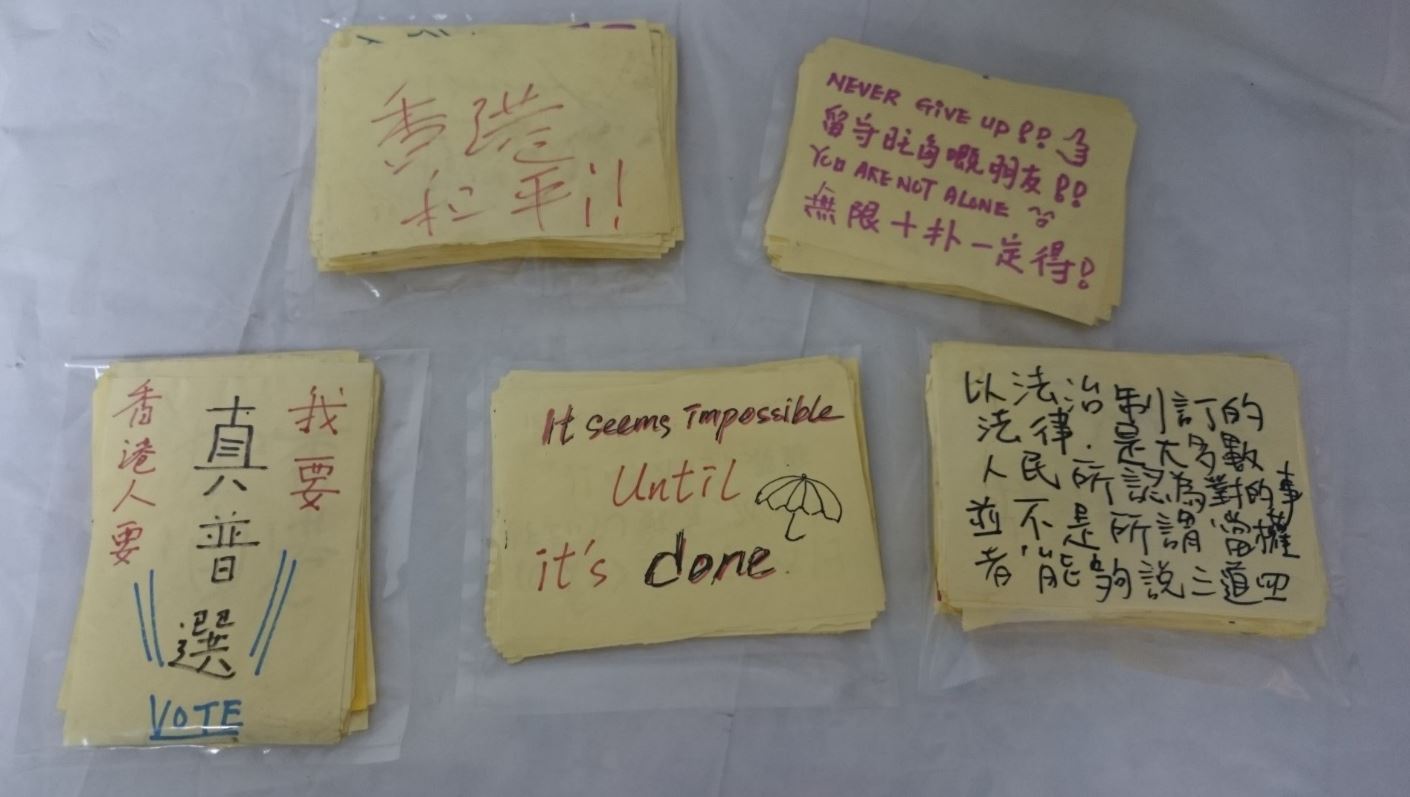

“We collected over 400 items and 1,000 posters in the 2014 protests,” said Dr. Sampson Wong, a co-founder of the Umbrella Movement Visual Archives. The volunteer group eventually donated their curated collection of protest objects to The Chinese University of Hong Kong, which the public can access through a digital catalog.

While protest-related art and documents risk police seizure, contentious areas of Chinese and Hong Kong history have become an active target of state activity and censorship. As the only museum in the world commemorating the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, Hong Kong’s June 4 museum launched a Kickstarter this summer, raising over $200,000 to digitize its archives in fear that its artifacts and historical files could soon be seized.

Mak Hoi Wah, the chairman of the management committee for the museum, told me that freedom and democracy were tenets of Hong Kong culture, pointing to the city’s annual commemorative events of the June 4 massacre as an emblem of the city’s political freedoms. This year, the annual candlelight vigil was banned for the first time ever, with officials citing COVID-19 restrictions.

“Without firsthand information, knowledge, and reports, we won’t be able to find the truth and hold the government accountable for their actions,” Mak said.

Though the museum is still formulating a systematic plan for digitizing its artifacts, it is planning on inviting scholars and artists to design online interactive exhibits. The website will be open-source, so their methodologies could be replicated for other human rights museums.

In addition to highlighting cultural artefacts, some Hongkongers have even attempted to preserve the physical streetscapes and visual aesthetic of the city in video games. One Youtuber recreated the entire city in Cities: Skylines, while games like Cage and Oblige are local game developers’ odes to their hometown’s intimate and domestic spaces. But cultural preservation is so much more than just uploading scans of physical objects and rendering heritage sites in virtual spaces. Some activists have exported their lived experiences as frontline protesters by developing Liberate Hong Kong, a VR simulation game where players dodge tear gas and rubber bullets.

But beyond the street battles fought, how can a city preserve its newfound sense of identity and unity forged by the shared defiance amid waves of suppression, gaslighting, and violence? Hongkongers’ have developed a local pride born from recognition of their culture and values, distinct from those of mainland China.

In an attempt to resist the rapid erosion of their hometown’s autonomy, pro-democracy emigrants have created social media spaces aimed at connecting and cultivating the Hongkonger diasporic identity.

“Hong Kong will be like Xinjiang soon,” said Matthew Li, referencing the Chinese region where Uighurs are being detained. He co-founded “Hong Kong Professional Network” (HKPN) three months ago, a group that congregates on Facebook, Linkedin, and Whatsapp. “By connecting the global Hong Kong community, we can try to preserve the Hong Kong culture and spirit.”

HKPN has the stated goal of professional skills training—the group hosts events, including resume workshops and work visa explainers, for Hong Kong emigrants—but their thousand-strong community shares a far deeper emotional connection. On Whatsapp, they send each other memes ridiculing Hong Kong’s politicians. They discuss which bakeries in San Francisco or New York make the best mooncakes. They fondly reminisce about shared childhood experiences, such as _bo laap_—wax-burning during Mid-Autumn Festival.

Similarly, almost 6,000 Hongkongers—most of them in the U.S. and Canada—have joined “Cantonese Parents,” one of many Facebook groups dedicated to the preservation of Cantonese. A common sentiment found in these groups is how Cantonese, a nuanced and colorful language, is requisite to appreciate Hong Kong culture. The group’s members share crowd-created digital resources, from cartoons dubbed in Cantonese to homemade flashcard PDFs for other parents to download. In a hobby-project, one Hongkonger developed a website that helps musicians navigate Cantonese’s tricky tones and easily find rhyming words for lyrics.

While these efforts were commendable, I wondered how effective they were in preserving culture for future generations, so I reached out to Dr. Randall Mason, an associate professor in historic preservation at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Preservation is always a reflection of contemporary culture,” he said. “We have to get comfortable with the fact that if we want to communicate the past, it’s a creative process and not just a preservation process. It would be crazy not to use these digital tools.”

A concern that frequently came up in my conversations with archivists, hobbyists, and academics, was how these efforts by passionate Hongkongers are scattered and disorganized. Dr. Wong, the archivist, described how most museums and institutions in Hong Kong—entities that should be bearing the responsibility of aggregating disparate cultural media and heritage materials—are government-funded and consequently have little interest in these efforts. As a result, archival websites are easily lost. Social media groups stay noisy. Digital resources lack spaces for conversation.

A virtual place to see and remember Hong Kong may not capture the smell of incense as one walks past Wong Tai Sin Temple or replicate the sweltering heat and humidity that envelopes the city every summer, but Hongkongers could walk around a virtual Victoria Harbor at sunset, watching every skyscraper flicker to life. They could browse through a gallery of protest street art that has long since been destroyed in real life.

It is also naive to ignore how current digital efforts to actively safeguard Hong Kong’s collective memory and identity may be considered secession under the new National Security Law. As evidenced by last week’s arrest of a pro-democracy chat group’s operator, the more Hongkongers engage digitally, the more vulnerable they become. All the Hongkongers I spoke to acknowledged the risks associated with their efforts, though some were defiant.

“We just really fucking love Hong Kong” is a slogan that has recently echoed around the city. In the simplest terms, it encapsulates the one common sentiment of every Hongkonger who has attended a protest, digitized an artifact, or considered a virtual alternative to the cherished place they once called home.

from VICE US https://ift.tt/3hpD1u9

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment