When Lydia Pang, a design director at Nike, decided to make a zine about the foods of her family's Hakka culture, she knew she wanted to call it "Eat Bitter."

To "eat bitter," in Pang's perspective, is to endure hardship before being rewarded by sweetness: a duck dish that takes three days to brine, braise, and roast; rice that must be soaked for five hours. "It's about pushing yourself to be uncomfortable," Pang said, "and I think that's a lesson we're all certainly sitting in right now." To her, the spirit of the Hakka people—the Chinese cultural group whose history has been shaped by displacement—is one born of adaptation.

Growing up in Wales but with Hakka roots on her father's side, Pang's dinner table—filled with dried meats and seafood, sharply scented broths and stews—looked unlike anything her friends were eating. Her grandfather's sticky char siu filled repurposed butter containers; and pork belly, topped with garlic and preserved black beans, simmered on the stove until it turned "wobbly." Meals were served family-style, and "you'd just pick some of these little pungent goodies for the top of your rice," Pang said.

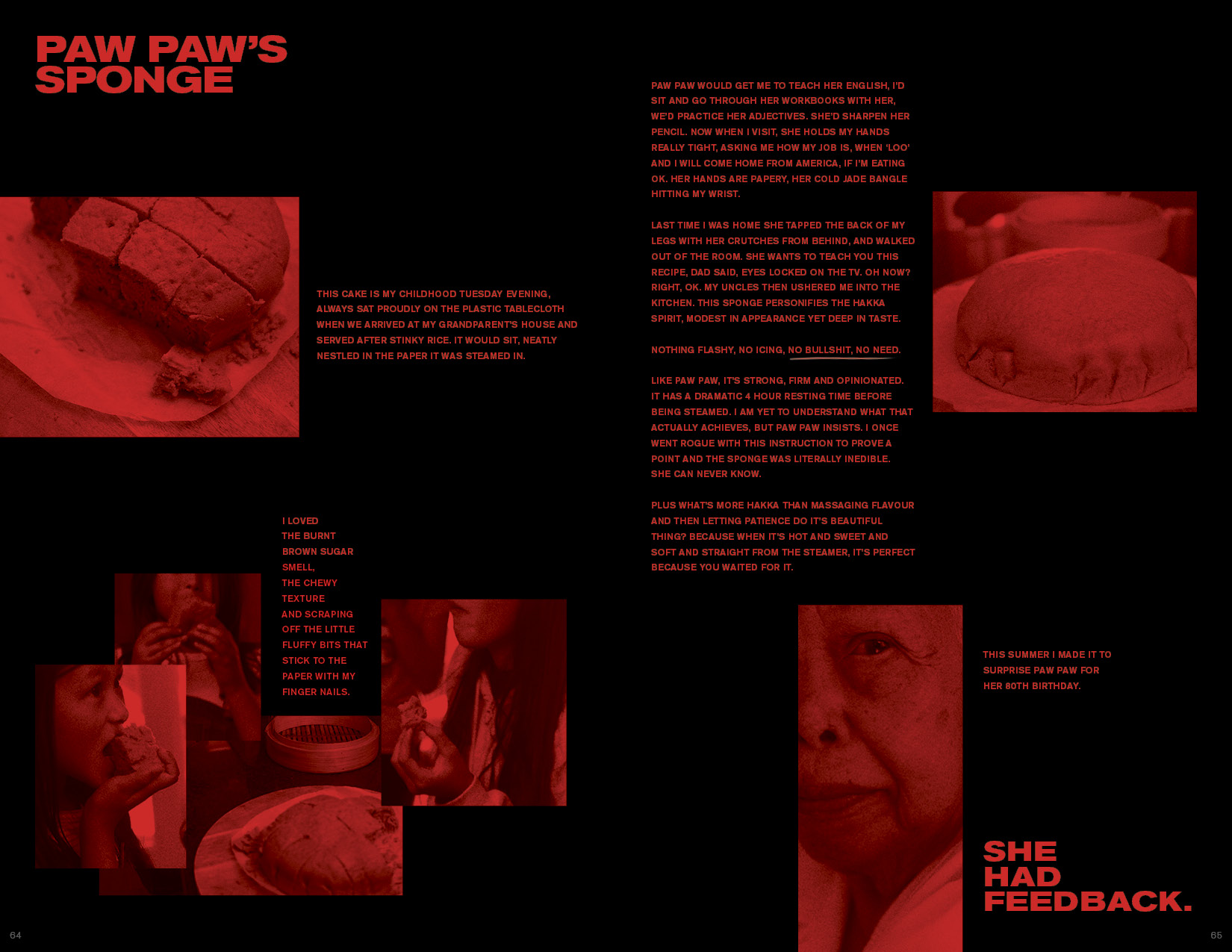

Eat Bitter isn't just a selection of these recipes, depicted in bold images by collaborator photographer Louise Hagger, but also a collection of stories and conversations that have rattled around Pang's family dinner table for years. With her grandparents growing older, and with the sense of responsibility that comes with being the eldest in her generation, Pang also saw the project as a way to record her family's cultural knowledge.

Though Pang always knew she was Hakka and spent most summers in Hong Kong, she felt her culture simplified by the lack of diversity in Wales. "I kind of did that to myself, where I was like, oh, I'm half-Chinese. I didn't really consider the nuances of what that meant," she said. While living in more diverse cities like London and New York—where she worked as the creative director of the now-VICE-owned Refinery29—she was surrounded by people proud of their varied cultures, and she became more curious about her own. "I suddenly felt like I really one-dimensionalized my Chinese background; let's dig into that."

The history of the Hakka people can be traced through five forced migrations between the fourth and 19th centuries that eventually pushed the majority of the world's Hakka population to the southern province of Guangdong. In fact, "there would be no Hakka without migration," according to the Hakka Affairs Council of Taiwan, and the word itself translates to "guests." As a result of land conflicts, Pang's ancestors were forced to make homes on new scraps, learning to "adapt, graft, take risks, and be strong enough to survive these obstacles in their path," Pang writes in the zine. Today, the diaspora extends all over the world.

The need to adapt and make do with limited resources extended to Hakka food. Preserving meats and seafood and then rehydrating them, for example, was another test of resourcefulness. Cookbook author Linda Lau Anusasananan has described Hakka cuisine as a "nomadic type of 'soul food'" that is "earthy, honest, and robust" as a result of hardship and oppression. With Cantonese and Sichuanese cooking dominating the landscape of Chinese food in the United States, Hakka cuisine isn't as immediately recognizable. (It's more widely known abroad: In 2014, the government of Hong Kong listed Hakka cuisine in its "First Intangible Cultural Heritage Inventory.")

"I think [that's] because it's nuanced, it's not as glamorous, and it's harder to get in… It takes time to make, it's not convenient, and it's not pretty," Pang said. "Hakka is about nurturing the flavor; having patience; really, really, really investing yourself and your time into that meal being something that is nutritious, and something that isn't about anyone else. It's not Instagrammable; it's about nourishing you and your family."

As Anusasananan wrote in 2012's The Hakka Cookbook, not only are many non-Hakka people unfamiliar with Hakka food, but the cuisine is also getting lost within Hakka families, for whom assimilation, changing preferences, and busier lifestyles have prevented younger generations from learning ancestral foods. Like Pang, Anusasananan described her cookbook as a way of connecting with her family's history and passing information on to preserve Hakka cuisine.

The entire Eat Bitter project took on new meaning for Pang during the events of 2020. What started in August 2019 as a "somewhat self-indulgent exploration" of her own identity through food morphed entirely as a result of the coronavirus pandemic and rising xenophobia. "I suddenly realized that food and this creation could become a meeting place for dialogue around Chinese culture more broadly," Pang said, "and actually, it was my responsibility as someone who is half-Chinese to take on the fact that this is a complex thing to discuss."

In response to the pandemic's effects on the Chinese community, Pang wanted to defend and protect her culture. Now, a portion of Eat Bitter's proceeds will go to Welcome to Chinatown, a grassroots organization that provides resources to hard-hit businesses in Manhattan's Chinatown. (The rest will ensure that anyone who worked on the zine is compensated fairly, a priority given Pang's creative background.) Though Pang was "astounded" by the number of pre-orders she's gotten since sales opened earlier this month, she says she's not trying to make money with the project. Rather, it's given her a way out of the darkness of this year.

It's not just Pang who's eating bitter now; it's all of us, in the varied and endless hardships that the events of this year have made even more stark. "I already had the name before, and then I looked at it and was like, fuck, if there was ever a year where the whole world is eating bitter and enduring hardship before seeing the light and before tasting sweetness, it was now. I felt like this has grown into a conversation around protecting my culture and celebrating it as well," Pang said.

The zine is an attempt to mark down history in Pang's own way: via her family's story and their foods on moody, black-and-red, punk-inspired pages. "It's about holding space for a culture forgotten—and a cuisine forgotten—and I think that is important."

Photography by Louise Hagger/Food styling by Valerie Berry/Assistant food styling by Song Soo Kim/Chinese calligraphy by Henry Chung/Set design and prop styling by Alexander Breeze/Graphic and web design by Roo Williams/Retouching by Sam Reeves

Eat Bitter is now available for pre-order at eatbitter.co.

from VICE US https://ift.tt/3bKEeuI

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment