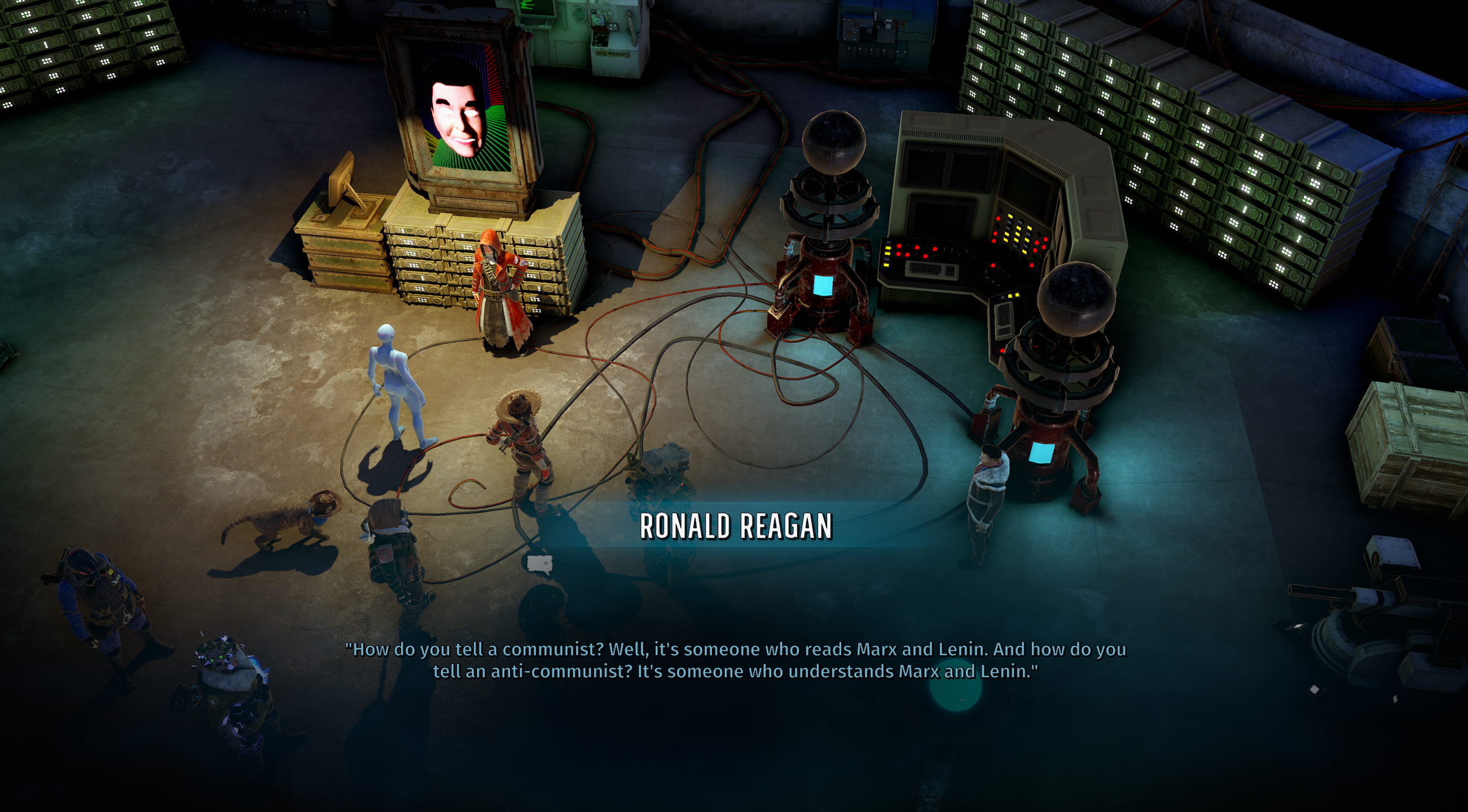

America is over but there are a few desperate holdouts and surviving the nuclear apocalypse has made the survivors strange and brutal. I only had bad options. Almost thirty hours into Wasteland 3, I could make a deal with Reagan worshiping cultists who wanted a new body for the AI running a simulation of their God-President, treat with Godfishers, or take my chances with a group of robots that "Reagan" had informed me were godless communists.

Seeing as the Godfishers dismembered travelers and attached their bleeding torsos to kites in an attempt to call down the blessings of the gods, and the Reagan AI only seemed able to repeat bits of the Gipper’s speeches, I decided to take my chances with the robots. Getting to them, though, would require me to slaughter my way through a camp of heavily armed Godfishers. It could be avoided by destroying the servers housing the Reagan AI, which might be a good way to cement a friendship with the communist robots at the Denver airport anyway. But it was a lot to stake on the possibility that the robots were real, and that they were cool.

Like I said, I only had bad options. But that’s Wasteland 3: a game whose choices reverberate throughout the game, from the opening moments of character creation to the smallest interaction with NPCs. What you say and do matters. Who you kill or choose to let go may come back to bite you in the ass hours down the line.

A lot of RPGs make this promise, but few deliver on it anywhere near as well or comprehensively as Wasteland 3. Before setting out for Denver to deal with the Reagan-cult, I got a call from a shady contact. He was posted outside of a community of traders. He wanted to take control and was willing to cut me in if I helped him overthrow the regime. I liked the traders, so I told them about the plot and helped them clear out the rival cartel.

A colleague who is also playing the game got the same call from the shady contact but decided to put off helping either side and went to Denver. When he returned the trading area was wiped off the map and the rival cartel nowhere to be seen. A huge hub full of vendors, quests, and NPCs was completely gone because my colleague decided to prioritize a different mission. In Wasteland 3, the clock is always ticking and inaction can have consequences as dire as direct action.

It’s a game about political power in a peculiarly surreal American nightmare future. It feels both old school, harkening back to the turn based RPGs of the 1990s, and strangely of the moment, a gibbering comedic scream in the darkness of 2020.

In Wasteland 3, players take control of a squad of Desert Rangers—famed do-gooders from Arizona. Think the Texas Rangers of myth, not the Texas Rangers of brutal reality. When the game starts, the Rangers are on their last legs after the events of Wasteland 2 and are traveling to Colorado Springs to make a deal with a local dictator called The Patriarch for supplies. The Ranger’s caravan is wiped out on the way and only a few people, including the player characters, survive.

From there, the Patriarch sets you up in an abandoned Air Force base and charges you with rounding up his three wayward children. How I handled things was up to me. Wasteland 3 is part RPG, part tactical shooter, and part base management sim. I wandered the frozen wastes of the state of Colorado, treating with various factions, cutting deals and using violence when it’s necessary. As the fame of the Rangers grows, so too does its base. New recruits come and need jobs, new supplicants arrive with problems, and rivals come seeking redress for slights both real and imagined.

In Wasteland 3 I was not just a party of adventurers seeking fortune in the wastes, I was a political force with the military might to back up my will. I felt like the Rangers had the same influence on the world that major NPC factions had. For me, that has been the biggest draw of the game. I’m a political mover and shaker in an America torn apart by surreal nightmares. I am not playing the chosen savior of the wastes or a lone wander. I’m playing an organization, one with an ideology and belief system I’m shaping as I play.

Do I treat refugees with kindness or disdain? Will I murder lawbreakers, arrest them, or let them go? When I arrest them, will I turn them over to the Patriarch’s police forces or keep them in my own jail? Moment to moment, as I play Wasteland 3, I am shaping my own ideas of justice. I have a blanket rule that I don’t deal with slavers and that cut moral decision has cost me. Many of the factions in Wasteland 3 take slaves and there’s benefits to doing business with them. I’m shut out of the basement of my base because I wouldn’t deal with a slaver who had the codes, and I lost a powerful potential party member because he was a slaver.

These choices cut me off from powerful tools, but also changed my relationship with the people of Colorado. Random encounters in the wasteland, the prices of stores, and dialogue trees have altered. I never feel like I’m losing out, I always feel like I’m changing things.

Wasteland 3 is obsessed with the past. I often felt like I was playing a CRPG from 1992 done over with a coat of paint. Some of its punches don’t land and I could tell the writers were from an older generation. An extended beastiality joke in a casino doesn’t work, for example.

But Wasteland 3 hits more than it misses and its obsession with the past empowers its dark satire of American politics. This is a world where American culture stopped in the 1980s. In Gipper territory, a giant AI controlled statute of Ronald Reagan dispenses justice at the end of laser eyes. The AI takes multiple wives and calls them all Nancy.

A gang of nihilist clowns wants to let the world in on what it calls “the great joke.” The joke is that “the world is dead. Mock the weak and the stupid. Fuck shit up for laughs, or get fucked up yourself.” These men and women dress in clown makeup, strap dynamite to pigs, and use Catholic iconography done over with red wigs and foam noses.

The economic center of Colorado is an underground mall run by aging me in dime store monster masks. This Monster Army rode out the apocalypse in a bunker with a movie theater and horror movies. When they emerged to the wastes, they dressed like Jason Vorhess and Michael J. Fox’s Teen-Wolf.

It’s surreal, grotesque, and over the top. The music, a collection of dirge-like covers of American classics and sitcom theme-songs, reinforces its nightmarish and oppressive atmosphere. One of my squadmates is a cowboy hat wearing cat that smokes cigarettes. Another is a Latin speaking gunslinger I found imprisoned by the clowns. I have no idea what he wants or who he is, but he has followed me everywhere I go since I freed him.

Wasteland 3 set me loose among American nightmares and asked me to handle them. It gives players an ingress into a complicated political world and asks them to make political decisions that affect whole communities. In a lot of games, those kinds of decisions mean picking winners and losers based on the player’s morality.

In The Witcher 3, Geralt is at a remove from the decisions he’s making for many of the game’s sidequests. His decisions are complicated but the good guys and bad guys are usually clear. Even the “Bloody Baron” paints all its humans in a sympathetic light. It’s the supernatural forces that are wicked, controlling the fate of humans. Geralt is there to intercede. Often, he’s just there for the money. He can comment on the horror of the human characters without getting too involved.

Wasteland 3 asks you to get involved. You’re a political force in Colorado and “politics is the way we distribute pain." When you’re picking winners and losers, you’re deciding who will eat and who will have shelter, all while managing your status among the other factions and carving your own path to power. Ignoring a problem could mean the destruction of an entire zone. Doing what you think is right might mean cutting a deal with a lesser evil.

That’s politics in the wasteland.

from VICE US https://ift.tt/2QQ1yxl

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment