“Imagine a cricket ball” is how Troy describes the first rock he ever sold. In other words: Big. $2,000 big.

This was the mid-noughties, when Troy worked as a “gutty” on the kill floor of an abattoir in Melbourne, Australia. Troy’s job was as a slaughterman, meaning he was one of the first to lay his hands on the cattle after they’d been funneled into the knock box and executed by a bolt gun to the brain. A cow’s brain, by way of comparison, is often no bigger than a baseball.

After the kill shot was fired it was Troy’s job to disembowel the animal by stripping out the entrails and internal organs so that the remaining carcass could be processed for meat. Most of what he pulled out would be shipped off to rendering plants to be turned into cosmetics, soap and pet food.

He remembers the day. A newly dead heifer had just landed on the gutting table, and Troy started by hauling out the cow’s stomach and intestines, dragging them aside so he could get to the liver. He reached in to grab the gallbladder—a small sack situated underneath—and noticed that it was swollen, deformed with what he initially thought was a tumour. It felt, he says, abnormal.

When he dropped the misshapen organ onto the table it landed with a thud, and something, “for some reason”, told Troy to quickly slice open the bladder. He ran his knife through the wet red flesh, unzipping it—and out slid the stone.

“That's when my eyes nearly popped out of my head,” he recalls. “I couldn't believe the size of it. I’d never seen a gallstone that big before.”

Surreptitiously, without wanting to attract too much attention, Troy grabbed the rock and took it straight to the wash basin, where he wrapped it in a plastic bag and dropped it down the sheath of his gumboot. Then he slammed his sharpening steel loudly against the sink.

“I pretended I banged my knee, and with a fake limp I limped to the lockers so as to not bend my leg in the gumboot—that way not damaging the stone,” he says. “I'll never forget that day.”

Through “some old veterans” at the meatworks Troy got in touch with a buyer, who called him directly and arranged to meet at a hotel in Melbourne’s western suburbs. He arrived on a Saturday afternoon, found the room, knocked on the door and waited, nervously. The door opened. Inside was a man in his mid-40s, casually dressed, and another man with a handgun attached to his waist. Troy was invited inside, “made to feel comfortable”. When he’d taken a seat he handed over a small, cubic tupperware container. The man with the gun stood off to the side and watched.

The buyer—a guy from Queensland in Australia’s tropical north—popped open the container and pulled out Troy’s cricket ball: a smooth, rust-coloured sphere, large enough to be clutched firmly in the palm of the hand. Anyone involved in the buying or selling of cow gallstones knows that a rock like that is worth something.

After weighing the gem on a set of jeweller’s scales, the buyer produced a suitcase full of cash, flicked it open, and shelled out a fat wad of fifty dollar notes. $2,000 for a 57-gram stone. The whole thing was over in less than 20 minutes.

“It was like a black market product,” says Troy. “These people were the middlemen for Chinese buyers, and back then, around 2005, the price was $1,000 an ounce. If a single stone was a certain shape then maybe it would fetch even more.”

On later occasions, when Troy brought multiple stones, the buyer would appraise them one by one—assessing their shape, size, colour; whether they had any imperfections or lumps of calcite—and then lay them out on the table in order of most to least valuable. Dark and pitted stones were worth significantly less than full-bodied, golden specimens, while pyramid-shaped rocks were the most highly coveted.

Over the course of four or five similar transactions, Troy estimates he made upwards of $8,000 selling gallstones. Another meat worker, Andy, claims he made somewhere around $10,000—enough to pay for his yearly family holidays to the Gold Coast.

“We always met [the buyer] in his motel room; he’d grade and weigh the stones, and then disappear into the bathroom and bring out the cash,” says Andy. “You’re probably aware that they’re used in Chinese medicine. I heard it had something to do with a chemical called bilirubin.”

Gut Healing

Bilirubin is an orange-yellow substance produced in the bodies of vertebrates during the natural breakdown of red blood cells—passing through the liver, gallbladder, and digestive tract before eventually being excreted as either bile or urine. When it isn’t excreted, a build-up of bilirubin often results in the formation of biliary calculi, or gallstones: hardened, muddy deposits that occur in the gallbladders of humans as well as cows, oxen and bison. If these stones aren’t removed they can block the bile duct, in turn leading to more serious complications including inflammation and death.

The medical consensus is that an excess of bilirubin in general, and gallstones in particular, are a bad thing: something to be diluted with acid pills, or surgically removed and thrown away. But traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practitioners tend to take a different view.

Cattle gallstones, or calculus bovis, have been prized for their purported medicinal benefits since at least the days of Ancient China, Persia and Greece. The former spruiked them as a herbal remedy, the latter as a universal cure for poison, and in Europe the rocks were used for jewelry and charms from the 12th century, following the Crusades, until as recently as the 17th.

These days, harvested cattle gallstones usually end up being dried out, crushed down and pressed into pills—more often than not with a cocktail of other ingredients like buffalo horn and deer musk—and their value can mostly be attributed to the antioxidant properties of the bilirubin, which Chinese medicine specialists believe can be used to treat and cure a range of ailments: from sore throats and fever through to heart disease, hepatitis and lung cancer.

Predictably, the alleged healing stones have recently gained even more popularity as people turn to alternative medicines to fortify themselves against COVID-19.

In February, while the coronavirus situation was still very much in the ascendent, the Chinese government and National Health Commission started recommending that people take something called the Peaceful Palace Bovine Pill: an over-the-counter Chinese medicine made with cow gallstones, buffalo horn, jasmine and pearl. Practitioners claimed these ingredients could help ease COVID symptoms in relatively innocuous ways, while critics questioned the safety of the concoctions.

Around the same time, President Xi Jinping started pushing the Chinese people to harness TCM as a source of national pride, insisting that as much importance ought to be placed on ancient Chinese remedies as on their Western equivalents. Many medical experts within China echoed his sentiment at the time, claiming TCM tinctures, potions and pills could be as useful in combating this novel coronavirus as they were during previous outbreaks like SARS.

“Western medicine does not have better answers to this virus,” Jiang Xianfeng, a traditional Chinese medicine practitioner at Beijing’s prestigious United Family Health hospital, told the New York Times in February. “The Chinese people have experienced these sorts of plagues many times in our thousands of years of history. If traditional Chinese medicine was not effective, the Chinese people would already be destroyed.”

It’s possible that this nationalistic push from the Chinese government is having a trickle down effect to gallstone dealers and brokers on the ground—whose prices appear to be at an all time high—as well as the farmers, butchers and meatworkers around the world who now stand to fetch an even higher payout for dropping a rock into their boot.

Gold for the Gutty; Grist for the Mill

A lot of the buying and selling of cow gallstones outside China now takes place via darknet marketplaces and private Facebook groups. Collectors looking to sell are encouraged to stash and dehydrate their stones in a dark location—bilirubin is photosensitive, and degenerates in light—before shipping them off to buyers overseas; ideally wrapped in tissues and nestled inside egg cartons, or secured inside biscuit tins to minimise the risk of breakages.

Such delicacy might seem excessive for a hardened lump of digestive fluid, but the precautionary measures more than pay for themselves. Though a rock’s value can drop significantly if it is chipped, cracked or even slightly damp, undamaged stones sold to the right buyers are literally worth their weight in gold.

VICE spoke to one gallstone broker who said he typically pays $57 USD per gram for “average quality” product, and $60 USD for stones that are “higher grade”. That same buyer later posted a callout on a private butchers’ Facebook group offering $50,000 USD for a kilogram, while a number of traders on other websites listed prices at anywhere between $45 and $77 USD per gram.

The problem is that substantial gallstones—like gold nuggets or oyster pearls—are rare. This broker claimed that for every 1,000 cows it was reasonable to expect a yield of 100 grams worth of the stuff; or, at his market value, the equivalent of just $6 per head of cattle. Every little piece of that adds up at Australia’s biggest abattoirs, of course, which typically slaughter several thousand cows a week—but even a cricket ball-sized stone is a drop in the bucket compared to the profits these businesses make from the meat itself.

Much more lucrative is for a worker on the kill floor, like Troy or Andy, to pocket as many stones as they can over a period of weeks or months and collect the bounty directly from a buyer on the side. That is, if they can get away with it.

Andy recalls how back in the 80s, 90s and early noughties it wasn’t uncommon for a company to let its workers keep the stones as a bonus or a gratuity—noting that “the job on the gut table was very hard to get into because of the rewards”.

But in the past 15 years, slaughterhouses have cottoned on to the rising market value of gallstones. It’s small money in the scheme of things, but it’s also grist for the mill: yet another animal byproduct to throw in with the horns, hooves, blood and bones that all feed into the abattoir's yearly earnings; a head-to-tail business model that turns almost every piece of the animal into profit and leaves no stone unsold. Money for nothing, really—and more to the point, money that the abattoirs want for themselves.

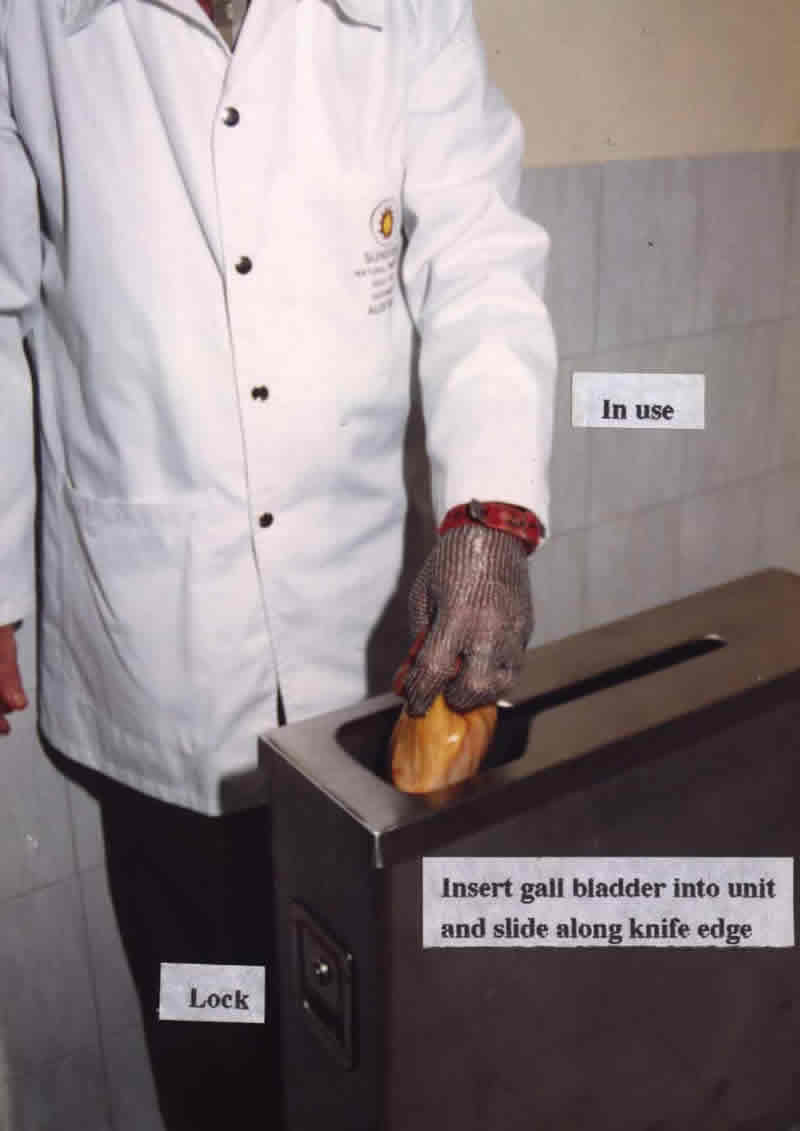

Now surveillance cameras preside over the gutting tables; workers are arranged in such a way that the supervisor can see everything from the one position; and gutties are forced to cut bladders open over stainless steel boxes with mesh baskets inside.

“Someone would slice the gallbladder holding it over the box, and if there was a stone in there it would fall into the box,” Troy explains. “The box would be padlocked, the foreman would hold the key, and the company would collect them and sell them. Although they wouldn’t tell you that.”

A Multimillion-Dollar Enterprise

Gerard Murtagh is the man who invented that padlocked box, and is now the Director of International Sales at Sunshine Trading: a family business that positions itself as “the market leader in Australia” for cattle gallstones. He’s also the reason almost every abattoir in the country now has a surveillance camera sitting above the gutting table.

Until 2003, Sunshine Trading was a boots on the ground operation that dealt exclusively with the meat workers: putting the cash straight into the hands of any gutties who happened to come across precious stones. Then Gerard, a fresh-faced and somewhat timid 19-year-old, started working for the family business and changed the industry overnight.

“As a young man I wanted to grow the business, so I would ring up abattoirs and say ‘what are you doing with your gallstones?’ And they’d be saying ‘oh we let the guys collect it’,” Gerard tells VICE over the phone. “Now I was like, I don’t want to be turning up to a town where I don’t know anybody and buy from a guy called Barry who’s just gonna meet me at the pub and try to sell me gallstones. I didn’t want to play that game. So I would say to those abattoirs: ‘you do know what the price of these gallstones is?’”

From there, Gerard launched what he describes as a nationwide education campaign: teaching slaughterhouses how to dry, preserve, store and sell cattle gallstones in order to yield maximal profits. Then Sunshine would come around every few months and buy the out-turn straight from management.

“The product itself is very brittle and very fragile, as well as expensive,” Gerard explains. “It can break, it can go moldy, it can disintegrate into powder if you dry it too quickly, but if you freeze it it’ll expand and break. They’re very delicate pieces of matter, so they’ve got to be looked after. Having someone go home and put them in their fridge or their jock draw is very different to the quality of product we get when we teach an abattoir to do it in-house.”

As another arm of the business, Gerard also started selling and installing Sunshine’s patent design dropboxes, or Gallstone and Bile Retrieval Units: waist-high, stainless steel vaults that “secure the gallstones away from any sticky fingers”, as he puts it. This did nothing to curry favour with the gutties.

“When you turn up into country towns you’re not the most popular bloke,” he laughs. “I’ve had all sorts of things thrown at me over the years, because I’m the guy that installed the box. I’ve had livers thrown at me when I’ve been on the kill floor; I’ve had one place where the guys are all throwing fat at me as I’m installing it.”

“We’ve even had our boxes completely destroyed,” he adds. “We’ve had to reinforce them; put new padlocks on them; put in higher grade steel. We’ve had the tops ripped off.”

Gerard’s entrepreneurial vision might not have made him many friends, but it turned his family business into an institutional juggernaut and gave them a nationwide monopoly over the gallstone white market. Sunshine Trading now deals with more than 50 abattoirs across all Australian states and territories, and rakes in some 200 kilograms—or, at the grey market rate, an estimated $11.5 million USD—of gallstones every year.

Sleight of Hand

Since the crackdown, sticky-fingered meat workers have had to change their tack if they want to go home with a gallstone up their sleeve. Gone are the glory days that Andy remembers, when it was simply a matter of feeling for lumps and emptying out the loot. Years later, working on the panopticon of the kill floor under the gaze of the cameras and supervisors, Troy’s methods had to be more covert.

“Actually extracting the stones wasn’t easy because you’d need to be discreet about it,” he recalls. “Not to mention they give off a bright orange dye, so hiding them in the pocket of your plain white pants was a challenge.”

Troy says that in the case of smaller stones and pebbles, “sometimes the hand was quicker than the eye”. But larger rocks called for a more devious, if less delicate, approach.

“You’d cut the whole bladder out and make it look like the guts were cut, and shit would come out,” he says. “Then the whole guts as well as the liver would be condemned and ‘discarded’.”

These sleight of hand techniques always put Troy in good stead, and in his 20 years as a gutty he never once got caught taking gallstones. But he knows someone who did. When asked to explain what happened to them, his answer is simple: “their employment was terminated.”

It’s not unheard of for rapacious gutties to get the axe for this reason. Ever since abattoirs started collecting gallstones for their own lockbox, pilfering them has been treated as a legitimate crime by the Australian authorities. Those caught red-handed face the prospect of instant dismissal, obviously. But in recent years there have also been more serious cautionary tales for anyone thinking of dipping their toe into the grey market.

Pockets Full of Stones

In May 2015, in the south Queensland city of Toowoomba, the Stock and Rural Crime Investigation Squad (SARCIS) raided the home of 38-year-old Dean Eames, a supervisor at the local abattoir, based on a tip-off that he’d been carrying out a one-man gallstone burglary over a period of six months. While searching the property officers uncovered a cache of stones weighing in at almost half a kilo. Collectively, the haul was deemed to be of “considerable value”.

Eames was arrested and ultimately sentenced to two months’ imprisonment after pleading guilty to the theft. Standing before the Toowoomba Magistrates Court he insisted that he was unaware of the monetary value of the rocks, and claimed he merely took them to eat so he could combat the fatigue of working two jobs.

It’s unclear where Eames got the idea that gallstones can be ingested as a stimulant—although there are medically contentious reports of calculus bovis being used as an “Awakening Brain and Sedating injection” to treat coma patients in China—or whether he did, in fact, start dipping into his own supply. But his defense alludes to a likely reason why so many meat workers still run the risk of stealing from the company, even when faced with the threat of instant dismissal and possible jail time.

Killing cattle for a living is hard, low-paying work. Current data indicates that the average hourly rate for a slaughterer or meat packer in Australia is just $16 USD, equating to an annual salary of $37,024—meaning that even a one-gram pebble of medium grade bilirubin can be worth more than three times a gutty’s hourly wage. Half a kilo is a drop in the bucket for the slaughterhouse, but for a worker on the kill floor it represents more than three quarters of what they make in a year.

It’s also unlikely that the price is going to drop anytime soon. Gerard tells VICE there’s “no doubt” that when the Chinese government promotes interest in bilirubin-based medicines, the gallstone market responds favorably—meaning a juicier payout for the risk-takers on the kill floor.

As long as gallstone demand rises and wage growth slides as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, the trend of pinching profits from the gutting table is certain to continue.

“It’s always going to be a temptation for people to put a stone the size of a golf ball in their pocket and pay their rent for the week,” Gerard says. “While people have the ability to steal and the need for money—and when you’re dealing with a product that is so rare and so expensive—that temptation is always going to be there.”

Follow Gavin on Twitter

from VICE US https://ift.tt/3dbrs94

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment