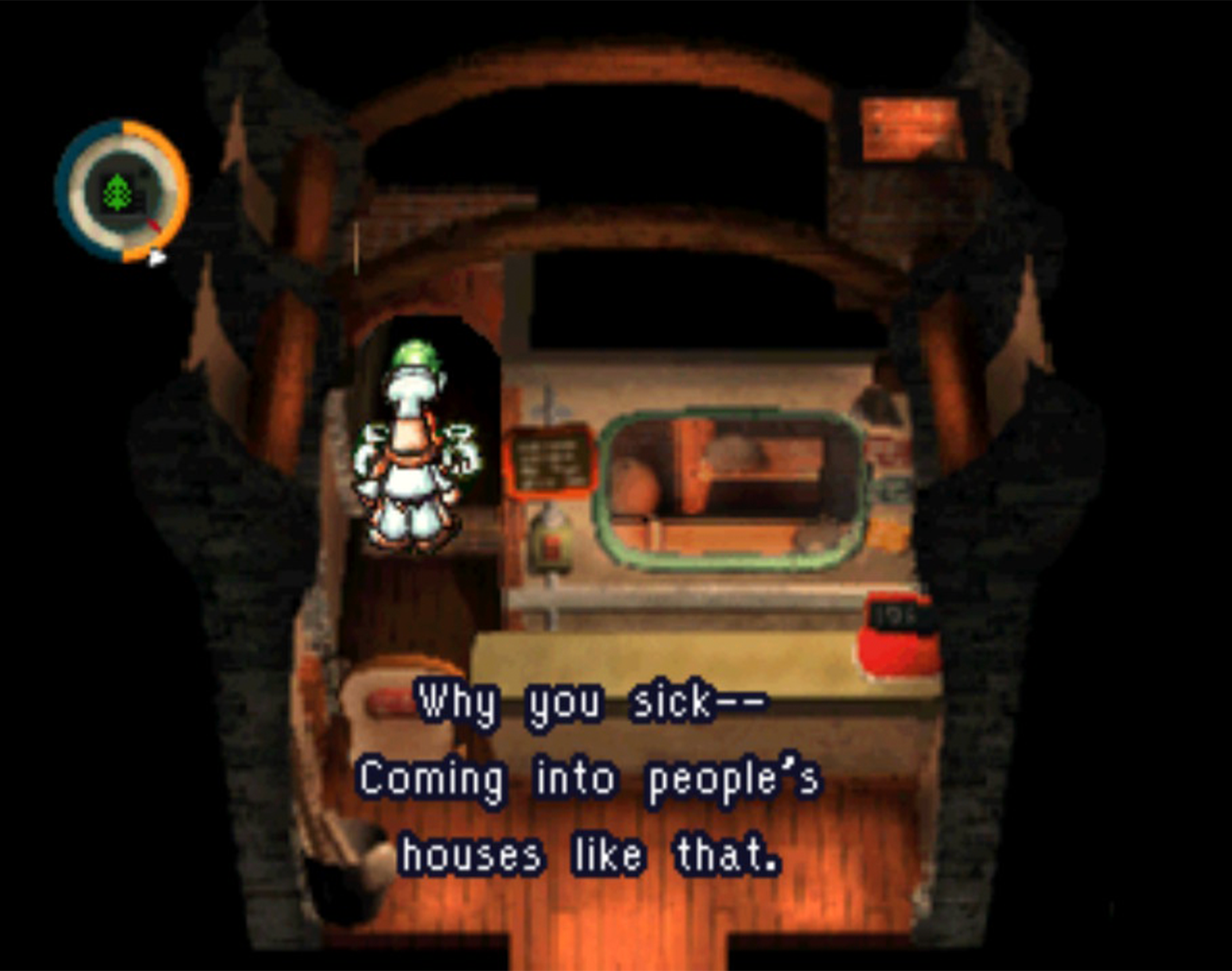

Moon has such an irresistible pitch for anyone who's been playing video games for a long time: "Why is it OK that this hero is breaking into houses and stealing items from people’s drawers? Why is it OK that this hero is killing thousands of innocent monsters?"

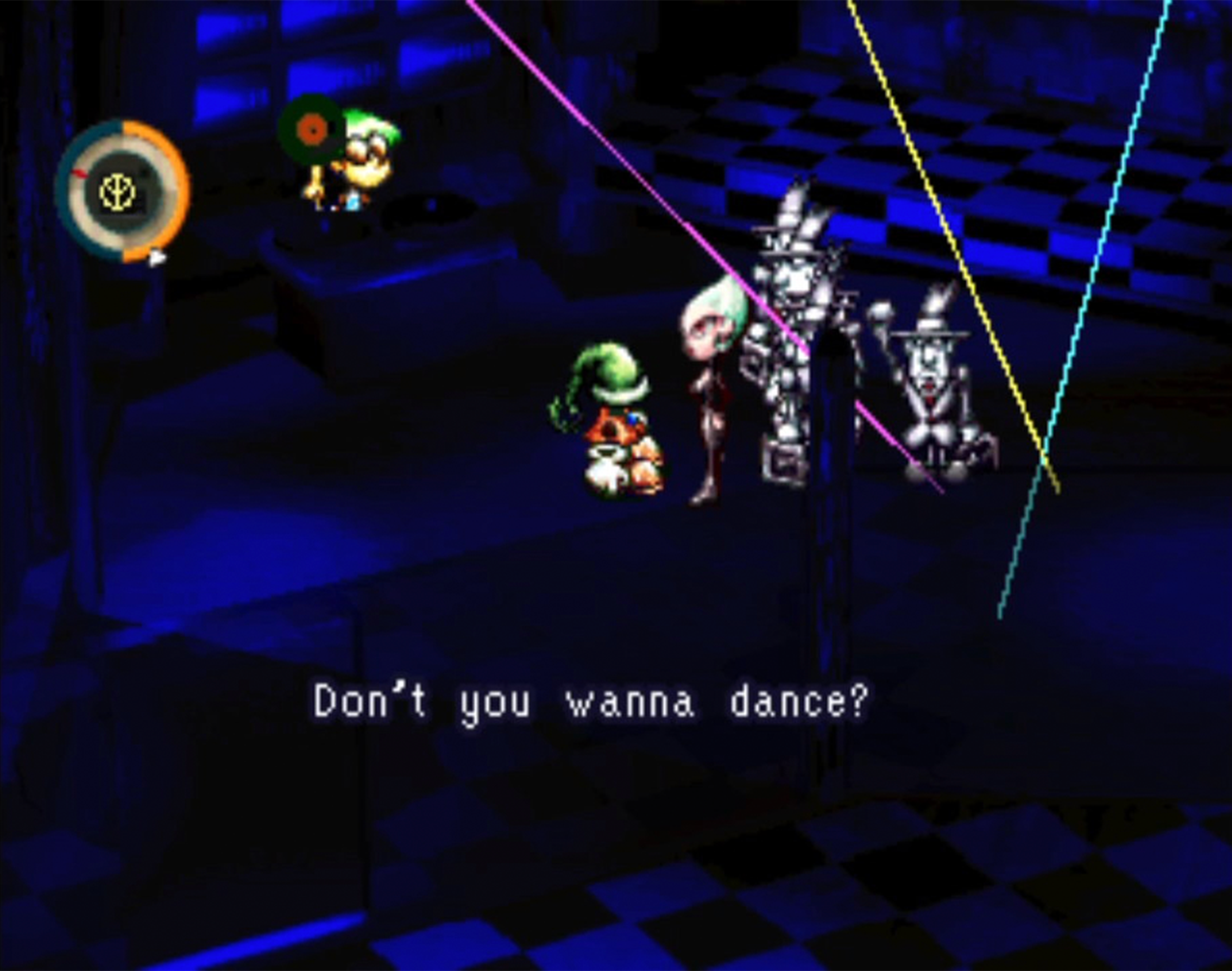

A sendup of Japanese role-playing game tropes popularized by franchises like Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest, moon has been dubbed the "anti-RPG." The phrase stuck for the game about a boy playing an RPG called "Moon World," and being sucked into the TV and having to become the hero themselves not by leveling up and killing enemies but gathering love.

"Don't be a hero," reads the game's tagline. "Experience the love. Experience moon.”

Satire—good satire—is hard. There's a reason it's genuinely rare in video games, which makes it all the more surprising to learn that moon was released all the way back in 1997 for the original PlayStation. It was supposed to be localized into English, and was even shown at trade shows back in the day, but for reasons still unknown, that release was cancelled.

This week, that changes, with moon arriving on Switch in English for the first time, 22 years after being released in Japan. I haven't had a chance to play it yet, because the developers have been working on the game up until the very moment it goes live on the eShop, but as someone who spent their youth picking up whatever JRPG they could find at the local rental store, regardless of quality, I'm really excited to revisit that time of my life through moon.

I did, however, have a chance to conduct an interview with the thoughtful and fascinating writer of moon, Yoshiro Kimura. The developer's JRPG credentials go way back, having been part of several Romancing SaGa games at Square. They're also responsible for one of the quirky and overlooked Chulip, a game about kissing, and a truly bizarre survival horror game, Rule of Rose. And you don't get the supremely popular Undertale without moon.

That more people, myself included, don't know who Nishi seems a shame.

So let's fix that, shall we? At one point, I was going to edit this interview down and just share some quotes, but once I started reading Nishi's answers, I couldn't stop. You should read the whole thing, too, and like me, anxiously wait for the chance to start playing moon ASAP.

VICE Games: Do you remember the first RPG you played?

Yoshiro Kimura: It was either Mugen no Shinzou 2 (AKA Heart of Fantasy), Black Onyx or Ultima III.

On the Onion Games website [publisher of moon ], there’s a saying attached to you: “I feel that indie games are a part of the beautiful nature of the Earth.” What does that mean to you?

When I’m confronted with the magnificence of nature, I’m sometimes literally moved to tears. I don’t think this is something unique just to me.

I had a chance to visit the IGF [Independent Games Festival] ceremony in 2012, and when I saw all those indie games on the screen, without really knowing why, tears started welling up, and I thought, “This is the same feeling I get when I see a snowy mountain, or the aurora, or chance upon a beautiful lake.”

Also, it says you’ve walked all over the planet? Is that a metaphor or...real?

It’s not a metaphor at all: it’s true. I’ve always had this tendency to wander since childhood, and I travelled all over the place, especially in my 20s and 40s.

I’ve experienced and enjoyed seeing the gorillas in a forest near the borders of Uganda and Zaire, the Aurora in Alaska, dawn in Machu Picchu, a personal-favourite forest in Switzerland, and an English mansion straight out of a horror film, owned by a playwright. All these experiences are a part of me.

So why revisit moon now? Why release it in English in 2020? What changed?

Quite simply because everything we needed to make it happen, happened. In order to release moon now, a series of veritable miracles were needed.

A producer at Kadokawa appeared who pushed it forward. (Editor's Note: The game's original publisher, ASCII, became part of Kadokawa in 2013] I got the greenlight from all the Love-de-lic members We found the thought-to-be-non-existent harddrive with the old code on it. I met an engineer who was well versed both in the programming techniques of the time, and modern ones, too. And, of course, the existence of Onion Games [the localized game's publisher].

But, before any of that, I think my biggest emotional motivation probably came from Toby Fox. He often came to Japan, and we’d go out for meals, and we were even interviewed together. We’re from different generations, but I love talking with him and respect him as a fellow creator and friend.

So, one day, Toby, Zun from Touhou Project and myself were interviewed. After it was done, Toby and I went and got coffee together near the train station and he asked me why I didn’t release moon worldwide. I told him there was no way I could, but thinking back, that was the first push that got me thinking, ‘why am I giving up? I could do this if I wanted to’. Localising moon so he could play it became really good motivation for me.

So, thank you, Toby!

What’s the process been like revisiting moon ? Do you enjoy looking at old work? Every time I look at something I’ve written in the past, all I want to do is delete it.

The first thing I want to say is that it was hard work! There was some new issue on a daily basis: problems with missing code and graphic data, problems getting the sound to work on today’s hardware the same way it did back then.

Then, any bugs required the script being checked, and firing up the game on the original hardware to check how it was supposed to work. It was a lot of low-key, grueling work.

I didn’t really find any room to enjoy it until the Japanese version was finished.

It was, however, thought provoking. Like digging in the earth to find a time capsule, I was strangely moved at times, like looking through an old diary or letters. It was like a flood in my brain: the script language, the characters’ lines, seeing how we’d fixed the bugs back then—all these memories washing over me.

Perhaps the most fascinating experience was the feeling that I was having a conversation with my past self. I was pointing out all the bad parts of moon, and he would lay into Black Bird and Dandy Dungeon in turn.

It was also fun when Kurashima-san [moon character designer and Onion Games art director Kazayuki Kurashim], my friend from the Love-de-lic [original developer of moon] days, dragged out all his original artwork and documents. There were just all these illustrations and ideas jotted down. Back then, our game development methodology wasn’t great and probably inefficient, but looking through these documents, I could feel the sheer power we had.

I can safely say this trip back in time was a positive one. It feels almost like I fused with my younger self and became stronger. I might just be imagining that part, though...

People talked about moon as one of the great “lost” RPGs because so many people didn’t get a chance to play it. Were you ever aware of that? How’d it make you feel?

Really? We were never conscious of this.

To be honest, we have no idea how interested people outside of Japan are in moon, but it does seem to be getting a much better reception than we imagined, so while we’re surprised, we’re also happy.

Moon was originally supposed to come to the United States, and the game was even shown at an E3 event, but the localization fell apart for reasons I wasn’t able to find before writing these questions. Do you remember what happened?

I remember it well. Localisation was underway in 1997, and I played a part-finished version. However, it was suddenly cancelled, and we never heard why. I still wonder what happened, but still can’t imagine.

On the website, you’re credited for “design & scenario & clay puppet.” Clay puppet? Can you...elaborate?

As a developer, Love-de-lic was a really odd place to work. It was like a band playing an ad-lib session, with ideas flowing freely from every direction. There was no ‘band leader’—we each respected one another, and we could express ourselves individually.

My personal expression was through the story, and the concept for the monster soul-catching system.

Work was, of course, divided up with certain people in charge of certain maps and characters, but before I realised it, I was deciding the overall plot, moulding how the story unfolded, and no one stopped me! They just let me get on with it.

story has many important minor themes along numerous vectors. My vision was to combine all of these together to convey a larger overall theme. These "sub themes" were along the lines of: "observing an RPG world with a hero from a different perspective," "a world free to explore at will," "riddles without heavy-handed hints" (we were big fans of Myst!), "a world without 'mob characters,'", "characters with individual human traits" and "a story without killing."

These may have sprung from my hope at the time as a traveller for acceptance of the world’s diversity. And these vectors come together, forming the main theme of the story, right at the very end.

Looking back, I think then, like now, we were struggling with this internal conflict: "is this all games can be?", "does making games hold any meaning?" and "why are RPG stories all so alike?" In a way, I think we were trying to end this conflict, and tear down the walls of such a confined space.

And then there were the clay figures! I really enjoyed making them. But it wasn't just me; everyone on the development team chipped in and made some. Personally, I really love stop motion animation, so being able to make those figures in between developing was so much fun.

Can you talk about your approach to localizing moon ? Among game fans, there are split views on localization, where some wish for the text to be translated exactly as it was written in the original language. Others believe language needs to be adapted to the culture it’s coming into. In this regard, how have you approached moon ?

My basic stance was that I wanted to find a translation which struck a happy medium between the original Japanese script’s humour, and natural sounding English. moon itself is a parody of the RPG genre, and its world is a fictional fantasy, so I didn’t feel the need to pay too much attention to ‘culturalizing’ it.

When you start thinking about culturalization, you have debates about whether something should be translated as riceball or doughnut, but that really wasn’t the case with moon. The croissants at a bakery are still croissants, whichever country you go to.

Related to that, how’d you meet [former Kotaku editor] Tim Rogers? I know he’s translating the game, but he’s also a game critic who is known for his very specific writing style. Why did you pick him to localize the game?

Tim actually helped with the translation for Dandy Dungeon, so this is not the first time we’ve worked together—but the translation’s quality is a team effort.

I picked him because his Japanese is very good and he has a strong understanding of the culture. I met him at Tokyo Game Show when I was promoting Little King Story. He spent most of the time asking me about Chulip rather than LKS, and we became friendly from then on.

After Tim translated it, six of us joined together to complete it: two native readers, a QA tester, a localisation programmer, a second translator, and myself. We did everything we could. Even then, I’m not confident we caught every error! It was such a huge undertaking.

This isn’t a question about moon , but I’ve long been fascinated by Rule of Rose , a weird but very cool survival horror game. Importantly, Sony passed on publishing it, and it caused a kind of moral panic in Europe over its depiction of children and violence. It never even came out there! What do you remember of that fiasco?

It was a huge failure! I remember it well. That game comes with a lot of bitter memories. Part of my sadness comes from that game not going on sale in Europe, but it’s also a bad memory for me.

Of course, I agree there were many immoral elements in it, but was it really that ‘evil’? The development team and myself approached that project in earnest, building a world around it: was it that evil? Were the earnest efforts of the development team and myself in building that world that evil?

Whatever anyone says, even if the whole world is against me, I still love that game. I can’t hate it. It may be a bitter memory for me, but everything in that world was born of my own imagination.

Every element—the world of the beautiful, yet terrifying girls, the bizarre imps, those spaces bound with rope, Stray Dog, Joshua, those dicey items—all the details are like my shadow. It’s like another part of me, as if a dark shadow cast by myself became my alter ego. I’d like to make another game like Rule of Rose myself, one day.

But I'm still anxious about how it would be received. Back then, it’s a fact that some people in Europe held very strong sentiments against it and I imagine some people would now, too.

You’ve been making video games for a very long time. Why keep doing it?

I don’t know. I honestly do not know the reason I’m making games!

The fact is I’ve even been forced to stop — and even run away from it — in the past, but as much as I think about it, I can’t work out why.

I’ve tried making a living doing something else, like working part time in a convenience store or a cafe, but it really didn’t suit me. So I’ve concluded it’s the only thing I can do.

Come to think of it, a long time ago, during my travels, I met a guy in Alaska who ran a lodge and he gave me this advice: ‘if you ever feel stuck, you revisit what you loved as a child.’ I think that may be what I’ve been doing.

At any rate, I think looking back at your childhood isn’t about industries and markets, it’s about looking deep into your heart. My loves were stories, music, and making games on 8-bit computers. I think that period of my life is where my soul lies, and it’s being able to feel the impulses welling up from there, which is why I’m still making games today. It’s a little difficult to put into words, but I hope that answers your question.

Follow Patrick on Twitter. His email is patrick.klepek@vice.com, and available privately on Signal (224-707-1561).

from VICE US https://ift.tt/2EK0qZR

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment