As the Brazilian government struggles to contain a fiery crisis in its wetlands, a similar disaster is unfolding to the south, in Argentina. In recent weeks, out of control fires have erupted across the Paraná Delta, an expanse of exceptionally biodiverse wetlands in eastern Argentina that lies near the country’s biggest metropolitan areas.

Spanning nearly 7,500 square miles, the Paraná Delta is a mosaic of wetlands, islands, and patches of forest prized both for its natural beauty and its myriad uses, including cattle ranching, beekeeping, fishing, and tourism. This year, though, the delta has been in the news for a more distressing reason: Giant smoke plumes are wafting off of it and spilling over nearby cities. Since the start of the year, satellites have detected roughly 15,000 potential fire hotspots across the Paraná Delta, with July alone adding close to 7,000 to that total, according to Gastón Fulquet, a coordinator for the not-for-profit Wetlands International who focuses on the Paraná Delta and the Paraguay River.

Fulquet says these are the most intense fires the delta has seen in over a decade.

“It’s quite a rare situation,” Fulquet told Motherboard. “It’s not that there is not fire in the Paraná Delta, but it has not reached this scale for at least the last 12 years.”

Ecologists worry that the fires could have a number of harmful effects on the environment, including destroying key habitat areas for the more than 700 types of plants and nearly 60 reptile and amphibian species that live here and sending ash spilling into local waterways, choking out fish that local people and myriad wetland birds depend on. In wake of massive, drought-fueled fires that swept the delta in 2008, scientists also observed significant losses of carbon from wetland soils.

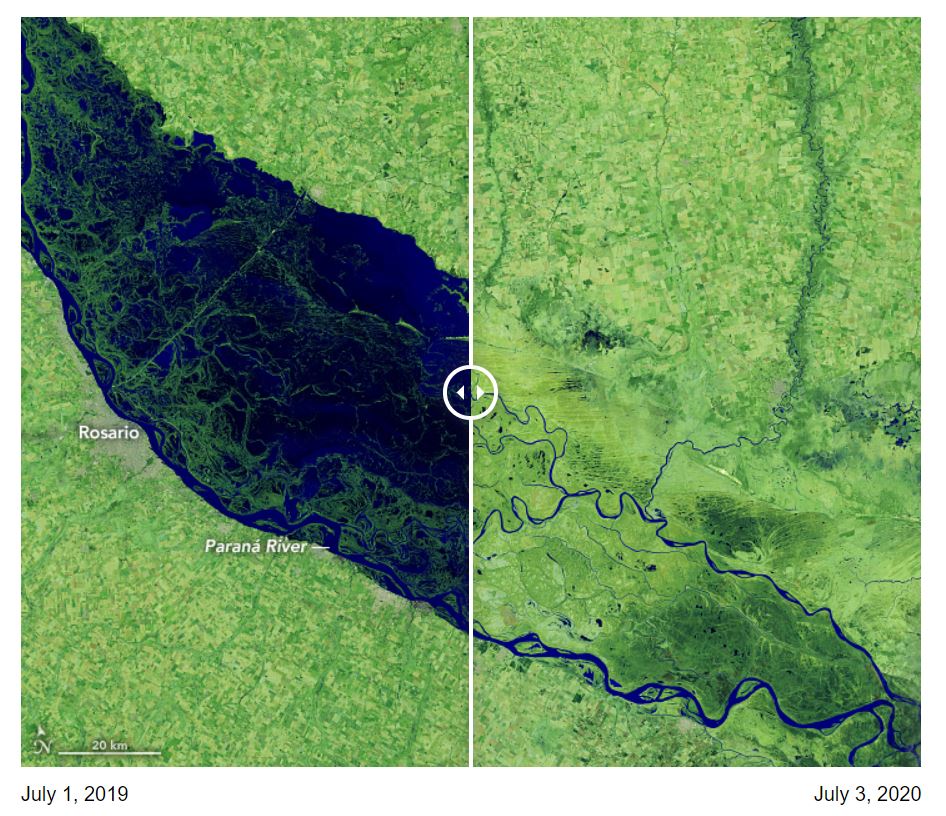

According to Fulquet, the situation is “very much connected” to what is happening in Brazil’s Pantanal wetlands to the north, which are part of the same vast hydrological system, the Río de la Plata Basin. Poor rainfall across the basin ultimately has meant less water flowing into the Paraná River in recent months. Combined with a dearth of rainfall over the delta itself, water levels have plummeted to their lowest point in nearly five decades, leaving the wetlands high and dry.

“It is a drought that has no precedent since 1971, and that means that any burning can turn into a fire,” said Manuel Jaramillo, General Director of the Fundación Vida Silvestre Argentina, a World Wildlife Fund-associated organization. “The organic matter of the soil usually has humidity, but due to the drought, it doesn’t have that humidity, so now it burns. It is difficult to put out the fire and the wind rekindles it.”

Fires are getting out of control quickly when humans provide the spark. Fulquet explained that people start fires in the delta for a variety of reasons, including to improve pasture for cattle and to clear grasslands for development. And while the province of Entre Ríos, where the fires are currently concentrated, prohibits the use of fire without express permission from authorities and enacted a 180-day fire moratorium in June, Fulquet says there is “little capacity to enforce these laws and regulations.” Many people seem to be ignoring them.

Out of control fires also pose a direct threat to the delta’s islanders, who Fulquet describes as the region’s “most vulnerable population,” as well as to first responders. Smoke from the fires, meanwhile, can affect sensitive populations in nearby cities like Rosario and Buenos Aires. On August 6, satellite imagery shared by Greenpeace showed smoke spilling over the capital in a stark echo of what occurred in 2008.

“The arrival of the smoke in Buenos Aires does nothing more than expose the dimension of the serious environmental problem that is occurring in the Paraná Delta,” Greenpeace Argentina campaign coordinator Leonel Mingo said in a statement.

In wake of the crisis, groups like Greenpeace and Fundación Vida Silvestre Argentina are calling for the establishment of a national wetlands law that would safeguard the delta’s ecosystems and coordinate management strategies at the national and regional levels. Fulque, meanwhile, hopes to see a strengthening of the Comprehensive Strategic Plan for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of the Paraná Delta (PIECAS-DP), an environmental management plan that was developed following the 2008 fires but which he says was “very much abandoned” under the administration of Mauricio Macri, who served as president from 2015 to 2019.

Ultimately, there needs to be better coordination among the many stakeholders who use the delta to prevent bad fire years like 2008 and 2020 from becoming normal. With climate change expected to lead to more extreme floods but also, potentially, deeper droughts in the future, that’s something conservationists are increasingly worried about.

“We have to be ready and prepared for situations like we have this year,” Fulquet said. “And I think since it’s not so common yet, we are not completely ready.”

from VICE US https://ift.tt/3ircTzQ

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment