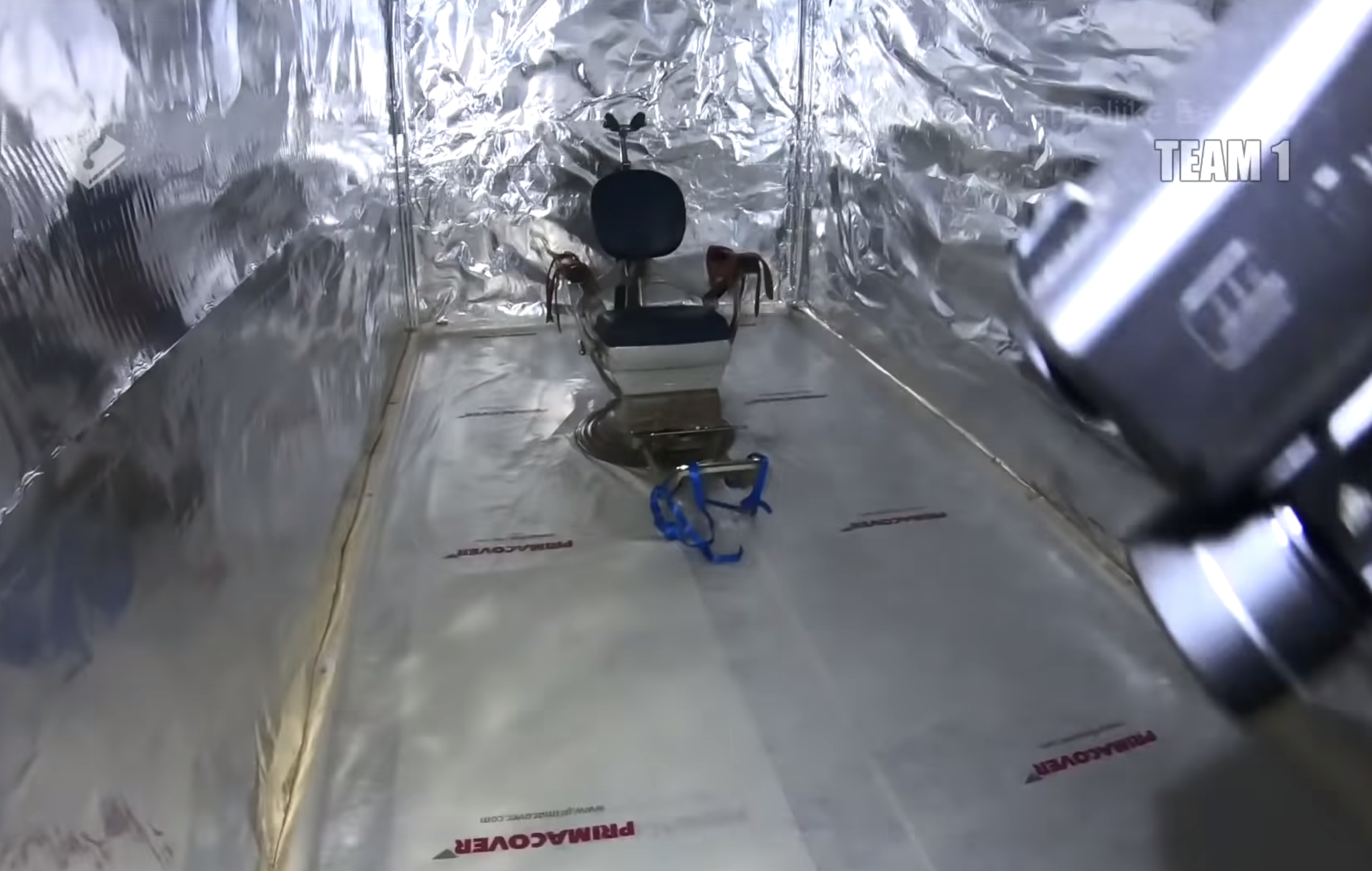

When, in early July, detectives discovered a secret torture chamber halfway between the giant ports of Antwerp and Rotterdam, it made a grim kind of sense that the room had been built in an old shipping container.

The extreme gang violence that has been unravelling over the past decade in Belgium and the Netherlands is linked inextricably to the high seas, seeping out of the two ports and into the streets of the region’s major cities.

In 2019, the head of America’s Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) chose to visit Antwerp, alongside Colombia, to state his determination to push back against global drug gangs. A series of shootouts and explosions in the Belgian city – home to the second largest port in Europe – have led to the founding of a special task force to tackle the rising problem of underworld drug gang violence.

Rotterdam and Amsterdam have been hit by similar rises in open gang warfare. In Rotterdam, at least three men were shot dead in separate gangland-style killings this spring, while a building was peppered with bullets and then bombed. Police suspect the violence was related to the interception of 4,200 kilos of cocaine by the authorities in the port of Antwerp the previous month.

In Amsterdam, there’s been a steady rise in underworld violence over the last eight years. In 2014, crime lord Gwenette Martha was mowed down in a hail of more than 80 bullets outside a kebab shop; a severed head was left outside a café in 2016; an anti-tank rocket was fired into the offices of a major newspaper in 2018; and, in December of 2019, Derk Wiersum – the lawyer for a state witness in a major mob trial – was shot dead in front of his wife outside their home.

Insiders say the torture chambers found during the EncroChat busts supposedly belonged to an alliance of local criminals working against the Netherlands’ formerly most wanted man, Ridouan Taghi – a Dutch-Moroccan alleged mob boss arrested in 2019 on suspicion of murder and drug trafficking.

So how has such a modern, otherwise peaceful part of the world – known best for its waffles, flowers and clean streets – become home to a steady stream of gangland assassinations?

The answer is cocaine.

A huge chunk of Europe’s coke comes through Rotterdam and Antwerp. In July of 2020, Dutch customs revealed they had seized double the quantity of the drug in the first six months of 2020 as the same time last year, mainly at the port of Rotterdam, while Antwerp is Europe’s main entry point for cocaine smuggled from South America. In 2019, a total of 61.8 tonnes of cocaine was intercepted at the sprawling 120-square-km port, a rise of 660 percent in five years.

“It’s a very fast movement of millions of containers through Antwerp,” says Bob Van den Berghe of the UN’s Container Control Programme. “Ships drop containers off in the port and quickly the ships are gone, which is an advantage for criminal organisations.”

An investigation in 2015 found that, at one point, smugglers had hacked into Antwerp’s security grid, allowing them to better plan smuggled cocaine shipments by tracking containers. There have also been instances of corruption at the port, with dock workers bribed or followed home and coerced by criminals.

As the profits from cocaine smuggling have spiralled, so has the violence. When a 200-kilo shipment was seized by Antwerp customs in 2012, the bust sparked a wave of shootings and retaliations across Belgium and the Netherlands, between an ensemble of mobsters who all suspected one another of ripping each other off.

By 2018, the murders of 30 people were linked to the feud, including that of Gwenette Martha. Two members of a Belgian crew known as the Turtles were kidnapped and filmed being tortured with a soldering iron. The war was later re-enacted in the 2018 Belgian black comedy, Gangsta.

The situation was getting so bad that, in 2018, Antwerp authorities decided to beef up security and tackle port-side corruption. However, they have admitted that they are still only finding, at most, just 10 percent of the cocaine trafficked through the port. From Antwerp, the drug is then taken to the Netherlands to be cut for distribution across Europe.

In March, it was Antwerp and Rotterdam that drug smugglers initially flooded with cocaine from Colombia and Brazil in anticipation of a lengthy COVID-19 lockdown. “The coronavirus did not stop the cocaine tsunami, and this year the maritime smuggling of cocaine is still on a very high level, in line with our record year of 2019,” the Administrator-General of Belgian Customs, Kristian Vanderwaeren, told VICE News.

Global crime syndicates – from Belgian and Dutch drug businesses to Italian mafias, British firms and mobs from Africa and eastern Europe – have established permanent bases in Belgium and the Netherlands, to keep business running smoothly. And this mafia invasion, along with the subsequent violence, has sparked very real fears that the region is becoming something of a narco-state.

The Netherlands has a long history with cocaine. In the early 1900s, the Dutch East India Company – having exploited and enslaved millions of people – began growing coca in its colonies in Indonesia. There was even a cocaine factory in Amsterdam, which supplied marching powder to all sides in World War One. When international treaties finally put a halt to the Dutch’s rampant coke dealing, Rotterdam emerged as a key import site for the illicit trade of the drug from South America. And when port authorities started to clamp down on trafficking to Rotterdam, crime gangs began moving coke through Antwerp.

Italy’s ‘Ndrangheta crime family has a foothold in both Antwerp and Rotterdam. According to mafia expert Dr Anna Sergi, the ‘Ndrangheta has established itself within communities of Calabrian immigrants from southern Italy, using restaurants and pizzerias to wash their money and maintain a presence without attracting too much attention.

“Normally, the ‘Ndrangheta are very hands-off,” said Sergi. “So you have certain key members who finance the [smuggling] operation, then they call the people they need and use their friends in local mafia groups to do their dirty work for them – and this is definitely the case in Antwerp.”

'Ndrangheta clans have also partnered with Brazil's most powerful crime syndicate, the First Command of the Capital (PCC), to ship cocaine through its coastal ports. Sharing borders with Colombia, Peru and Bolivia, as well as a long Atlantic coast, Brazil is now emerging as a jump-off point for the snowstorm bound for Europe.

But there are many other players in the coke business reaching out from these ports, such as Surinamese and Antillean gangs from the old Dutch colonies in South America and the Caribbean; the Italian Camorra mafia from Naples; the Irish Kinahan gang; Kurdish and Turkish-Assyrian clans; Albanian mafiosi; as well as local Dutch and Belgian operations.

Some of the most notorious participants are what local media have labelled the “mocro-maffia”, or Moroccan mafia. The crew behind Antwerp’s coke war were a Moroccan hash-dealing family known as the Turtles, who were part of a wave of immigrants who’d come to the Netherlands and Belgium in the 1960s and 70s as gastarbeiders (guest workers), with a large contingent from the impoverished Rif mountains of northern Morocco.

Many were treated “like cattle”, and with no attempts to integrate them, they were moved to boarding houses or ghettos. Out of that hardship came a class of entrepreneurs who specialised in importing hashish from their home country.

“The mocro-maffia now are basically the children or grandchildren of those I worked with,” said Steve Brown, a retired hash kingpin, who – with his Rif partners – brought tonnes of weed into Amsterdam in the 1980s. “Back in my time, we were the ones sending cocaine to Morocco. I went there 20 times a year and brought it to dealers there, because they liked it. But 10 or 15 years ago, the [Colombian] cartels began using Africa and Morocco as a go-between to Europe. Several groups were already smuggling hash to Spain and Holland, so it was quite normal for these groups – who had the know-how, logistics and the corrupted port officials – to start moving the coke.”

According to Salima el Musalima, a female imam from the eastern Netherlands, the rise of the mocro-maffia was not just about money. “My dad was one of the early drugs pioneers in hashish smuggling from Morocco,” she told VICE News. “It wasn’t just the money, because he was lousy at that. It's more the camaraderie, the dreams of making it big, the excitement, the whores, the rebel pirate lifestyle.”

She said the alienation some young Dutch and Belgian-Moroccans feel is, in turn, another factor drawing them to crime. “Many of the kids involved in drugs in my town have broken families. I see a lot of frustration: if you are a Moroccan youth, the media is against you,” she explained. “This is why the drugs world and the jihadists get a huge following. It offers the youth a platform where they are not the victim, but the aggressor. At a certain point, they say ‘f-you’ and enter the underworld, which has its own rules. The other alternative is jihad.”

Once reliant on Dutch networks for a piece of the cocaine pie, the importance of Antwerp as a cocaine port has led to the Belgians gaining more control over distribution itself. Their profits are reinvested in local businesses, especially in the poor immigrant quarters of Antwerp’s Borgerhout district. This has sparked a backlash from the far-right in Belgium, as well as the ire of the Flemish nationalist mayor, Bart de Wever, who’s set up a special task force to take on the gangs.

“The old-school rules and codes of conduct among the underworld no longer seem to apply,” says Dutch criminologist Dr Robby Roks, who has studied the underworld’s evolution over the past few decades. “Gangs used to focus their attacks on those directly tied to organised crime themselves, not lawyers or family members. Some of the shootings have been in broad daylight, in close proximity to schools, and also a few times the wrong people were killed. This seems to have to do with the actual hitmen being younger and much less experienced.”

While this corner of Europe won’t see the kind of narco-bloodbath witnessed in countries like Mexico anytime soon, recent events suggest violence associated with the cocaine trade is only going to get worse.

With thanks to Dutch author Teun Voeten. Niko Vorobyov is a government-certified (convicted) drug dealer turned writer and author of the book Dopeworld, about the international drug trade. You can follow him on Twitter @Lemmiwinks_III

from VICE US https://ift.tt/3kB5iQU

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment