"I will kill when instructed. I am Satan's little whore,” reads a diary note dated June 6, 2009—five months and two days since Nathan’s wife Kylie borrowed the family station wagon, drove to Bible study and never returned. He can see that it is her handwriting: a familiar, neat scrawl, like a lot of the confessional letters that came into his possession 12 months after his presumed soulmate walked out on him and his son.

“If I disobey I die,” reads another. "I am a bad girl and I deserve this… I'm ugly, I am nothing. I only matter to the cult."

Nathan remembers the afternoon vividly. Kylie, who had struck up a friendship with a small group of fellow Christians in the lower Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, was preparing to head off to one of her increasingly regular women’s Bible study sessions. He was happy for her. Having suffered several brief but severe bouts of postnatal depression following the birth of their then six-year-old son, Liam, it was a relief to see her socialising with what appeared to be a generous and like-minded group of people. She said she’d be home for dinner.

Other notes in Nathan’s collection are written in a hand he doesn’t recognise—most likely scribbled down by various members of the group, he suggests, or possibly one of Kylie’s multiple personalities, of which there are now allegedly hundreds.

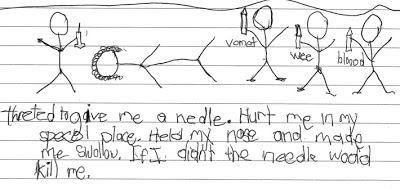

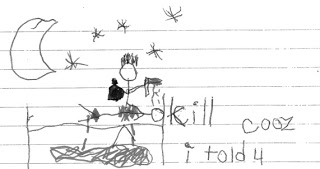

Some of the missives appear to have been jotted down during the “counselling sessions” that started taking place at the meetups in the weeks leading up to Kylie's disappearance. Many look as if they’ve been scribbled down by a child—an infantile version of Kylie’s handwriting—and describe hyperviolent scenes of torture and abuse: dogs hanging from trees; babies being decapitated; men having their tongues cut out and their mouths stapled shut and their eyes burned out with flaming sticks.

All of these letters were passed on to Nathan 10 years ago by another man, Wayne Donges, who lost his wife to the same group. “These were lying about the house before my wife left, and I collected them,” Wayne told him at the time. “I can't believe it, but they kept notes on everything.”

The notes Wayne gathered read like dispatches from another realm: a world of angels and demons and Christian mythology, all allegedly operating right under Nathan’s nose, in the leafy suburbs of the lower Mountains. They are a case history of a woman who fell prey to a fanatical religious sect, and a rare window into how good people get sucked into bad cults.

More than that, they are handwritten testimony to a series of events so surreal that, for years, Nathan’s constant refrain was “this is the kind of thing that happens to other people, or in movies, or on television”. He’s long since come to terms with the fact that it was real, and it happened to him.

Until 2009, the lives of Nathan and Kylie Zamprogno were what many people would call unremarkable. Nathan included.

They had just moved to a small town near the foothills of the Blue Mountains: a quiet part of the world known for its charming village communities, its dramatic natural scenery and, as a semi-ironic joke among outsiders, its “cults”. They owned a house, both worked at the same non-denominational Christian school—Nathan in I.T. and Kylie as a receptionist—and drove their 6-year-old son to Kindergarten every morning in a Subaru Forester station wagon. It was, as Nathan tells it, “the good life”.

“What typified our marriage and our family life was how ordinary we were, and how fortunate we felt to have a conventional family,” he tells VICE over video call. Then he delivers a line he’s become fond of over the years. “Horror stories usually start with an ordinary scene, and then, by degrees, turn sinister. And that’s exactly what happened in our case.”

With the clarity of hindsight it’s easy to pinpoint the incremental steps by which sinister forces entered the Zamprogno family’s orbit—but at the time, the sequence of events were deceptively unexceptional. Kylie had started working casual shifts at the school until she was healthy enough to resume her dream job as an emergency nurse at a major Sydney Hospital. The worst of her depression seemed to be behind her. She was making friends, and before long a tight-knit group who had associations with the school board had invited her around to study at their weekly Bible group.

“I kick myself now, because that's when the trouble started,” says Nathan. “No one recruits you to a cult by saying ‘hey, join our group and we'll ruin your life.’ But at the time I just had no idea. So off she went on odd evenings to socialise with this group.”

Gradually these “odd evenings” became more frequent. They ran later. On more than one occasion Nathan recalls sitting up past midnight, waiting for Kylie to respond to his messages. He had started noticing changes in his wife and was worried she was becoming unwell again. More often than not, another woman named Virginnia—the host—would reply: Kylie was undergoing counselling, and would call him in the morning.

On the morning of January 5, 2009, Kylie didn’t call. She didn’t come home, that day or the next, and hasn’t been home since.

With his neatly buttoned shirt and soft expression, Nathan is affable in his appearance. But there is also a hardness to him. He is at once polite and disarmingly candid; confident, but not without a sense of guardedness. He describes himself as a good judge of character, an optimist but also an empiricist, and a reluctant agnostic.

“I’ve seen enough evil, enough religious sanctimony and hypocrisy done in the name of Jesus to last me a lifetime,” he says. “Christians have turned me away from the church.”

In 2010 , Nathan joined the committee of the Cult Information and Family Support group (CIFS), Australia’s leading advocacy network for cult abuse. He counselled people who had lost loved ones to cults, or come out of cults themselves, and who needed to process the experience.

“People respond to cult situations in different ways,” he says. “Some people when they come out of cults withdraw into themselves, while there are other people who feel really angry at the years of their life or the normal relationships that they were robbed of, and they stay good and angry.

“I am in that camp, but I’m odd in the sense that I was never in the cult. I lost a loved one to a cult. And I went on the warpath.”

It wasn’t until more than a year after Kylie left that Nathan found out what had really been happening at the Bible study meetups: when Virginnia’s husband, Wayne, handed him a tranche of notes, scribbles and diabolical ramblings that documented the whole thing.

“They met here,” Wayne told him when the two of them first convened, in the dining room of Wayne’s house. Wayne pointed to a series of smudges above the doors and windows. "Do you see those greasy marks, Nathan? That's where they made little crucifix marks with holy oil. To keep the demons out.”

Wayne went on to explain that the group had been “treating” Kylie, and had diagnosed her with a condition known as Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID—previously Multiple Personality Disorder) where an individual’s psyche splinters into a number of distinct personalities, or “alters”, usually as a coping mechanism for intense childhood trauma. They believed that in Kylie’s case, that trauma happened to be repeated incidents of Satanic ritual abuse.

During her treatment sessions she was encouraged to elicit memories of being horrifically abused by her own family, reciting allegations that, among other things, she was forced to live under the house and was fed like a dog; that she had boiling water poured into her ear; and that she was taken to bushland locations by hooded figures and forced to witness human sacrifice. “All very, very wild claims,” according to Nathan. “Kylie was the eldest of four siblings, and the others reported a completely normal and loving upbringing.”

For Virginnia and the others, though, it made perfect sense: such gratuitous cruelty and abuse, at such a young age, was precisely the kind of thing that typically triggered cases of DID. In their view, Kylie’s mind had fragmented into hundreds of alters as a way of escaping harrowing memories from her past. Some of these alters—going by names like Hope, Joy and Truth—were childish in their disposition, while others—going by names like The Dark One—were considered demonic.

"Some of the alters wanted to hurt her,” Virginnia reported. “They would go and drink bleach, they would try and get her hand in the fire, they would run in front of trucks. So we kept the doors locked to keep her safe."

Behaviours that most people might have interpreted as signs of serious psychological distress were, as far as the group was concerned, evidence of Satanic influence. And beyond locking the doors and shuttering the windows, they believed there was only one remedy for such a thing.

“So Kylie was subjected to exorcism,” says Nathan. “In Australia, in the twenty-first century… She had a genuine mental illness but they were diagnosing her with demons and casting them out.”

It was around this time that Nathan received some disturbing correspondence from Kylie: a suicide note, addressed to their son. Certain scribblings in the diary from around this period make similarly ominous declarations. “I will obey at all costs” reads one. “The only way out is death" reads another.

The last time Nathan saw Kylie in the flesh was half a decade ago. He has no trouble remembering how she looked at the time: “Unwell, and vulnerable. And totally in the thrall of the cult.”

As far as he knows, Kylie never suffered DID before falling in with Virginnia and her crew—although he admits that she was inclined to tell “tall tales” from time to time, usually to curry favour or attention in social situations. Overall, he insists, there was no predisposition that would make her more susceptible to manipulation or religious indoctrination than anyone else. “That’s not the person I married,” he says. “Not at all.”

The implication is that this could happen to anyone: that under a particular set of misfortunes, perfectly unremarkable and ordinary people can, by turns, get sucked into the most unlikely vortexes. But it’s hard to get away from the question: How well can you really know someone? And how much of what appears from the outside to be a process of corruption, manipulation and radicalisation on the part of the so-called abuser, is in fact a conscious and consensual action on the behalf of the so-called victim?

To put it another way: how much agency does a person actually have when they uproot their life, walk out on their family and join a religious sect? In Kylie’s case, Nathan wagers some balanced odds: about fifty-fifty.

“Why is it that anybody gets involved in a cult?” he muses. “Do people get involved in cults because they’re stupid? Well, manifestly not: there are very smart people who fall for cults. So what is it? What’s the characteristic we’re looking for?”

It’s a question Nathan has spent a lot of time thinking about. The answer, he believes, is a particular kind of situational vulnerability in a person. Maybe they’ve moved to a new city and don’t have any friends, or have recently lost a loved one, or had a health scare. Maybe they’re in “a season of their life where they’re searching for answers to bigger questions”. These vulnerabilities, says Nathan, are things that cults are skilled at preying upon.

“I feel for my ex,” he tells me. “You have to understand that Kylie, as well as making some exceptionally poor choices, was unwell. And I will not victimise her further by painting her as the villain in this story; she is a victim, and it’s the members of that cult who I think are the real villains of the story.”

That story—of a wolf in lamb’s clothing luring a vulnerable Church-goer into a pseudo spiritual clique—is neither new nor entirely unique. Having spent several years meeting and speaking with others who had lived through similar experiences, Nathan came to realise that the methods by which his wife was indoctrinated into this group were overwhelmingly commonplace—taken straight from the playbook of How to Recruit Cult Members.

There are a number of techniques that these kinds of groups typically deploy, he explains. First they plant the seed. One or several members from the group will subtly convince an already vulnerable individual that they are special; that they have a unique destiny waiting to be fulfilled; that they’re being held back by the people with whom they associate and that there is another path they could plausibly take to achieve maximal self fulfilment or enlightenment. Often the means of reaching this state of fulfilment are placed just out of reach, prompting the individual to invest ever more into the group—either personally or financially—in order to come closer to attaining satisfaction.

From there the converts are coerced into believing that they should disregard the opinions and advice of others—especially when that advice criticises the particular sect within which they’ve suddenly found themselves. They are weaned off the affections of their families and friends and gradually have their “critical thinking toolkit”—the voice in one’s head that might otherwise raise alarm when something’s not quite right—suppressed.

“The things that are obviously dodgy to you or I, that part of a cult member’s brain has been anaesthetised,” Nathan explains. “And often when people come out of cults, it’s because their critical thinking faculties have woken back up and they realise they’re being abused and they leave.”

That never happened for Kylie. Instead, the group slowly tightened their grip around her, enlisting the help of like-minded fundamentalists to affirm her DID diagnosis and attempting to claim legal guardianship over her. Kylie was eventually deemed disabled in the eyes of the government, and therefore unfit for work. Virginnia is now her carer.

As far as Nathan is concerned, both Kylie and Virginnia became embroiled in a shared delusional disorder, or “folie à deux”—otherwise known as a “madness for two”. It was in Virginnia’s interest to keep Kylie sick, he says, possibly even exacerbating her symptoms so that she could adopt the role of a carer.

There’s a name for this. Clinicians call it Munchausen By Proxy when a caregiver fabricates, exaggerates or causes an illness or injury for a person under their care—usually for reasons unknown. The behavioural condition is broadly considered to be a form of abuse. But Nathan later discovered that, in Kylie and Virginnia’s case, there was also a financial interest to the arrangement.

“Neither, to my knowledge, have drawn a cent in wages for the last decade because they get government benefits,” he says. “One is a disabled person in need of care, the other is a full-time carer, and they get by on that income.”

It speaks to what might be the most obvious question in this whole ordeal. For all the pain and suffering they inflicted, what did the sect get out of it?

“The question that's often asked of cults or cult leaders is are they mad, or are they bad?” Nathan explains. “In other words: are they deceitful, and they know that this is all a scam; or are they deluded, and they actually believe that they are a Faithful Remnant of the church and that mainstream religious denominations are all being secretly controlled by devil worshippers who, at various times, gather in covens in remote locations to commit human sacrifice?”

This group, he’s concluded, falls into the latter.

“They actually believe these things. So what’s in it for them is ratification; a vindication of their particular spiritual theological belief. They believe they're engaged in spiritual warfare with a coven of Satanists operating up and down the Blue Mountains. And you can point and laugh at that, but you get to a point where you think: this isn’t just ridiculous, it's dangerous. People are being hurt.”

It is for this reason that Nathan and CIFS have been advocating for the Australian government to clamp down on the predations of cults by tightening restrictions around behaviours, as opposed to beliefs.

“You can believe the moon is made out of cheese if you want to,” he explains, “but if you start abusing people psychologically, and perverting their psychological care, and draining their bank accounts, and weaning them off the affections of their families, that's a violent act. And there should be some consequence for it.”

As it turns out, there isn’t. Although Australian law clearly prohibits acts of kidnapping, fraud, and holding a person against their will, there are no laws against brainwashing, scaremongering, or coercion. Nathan and CIFS contend that these things constitute forms of psychological abuse—but there is no clear legislative definition of what “psychological abuse” actually looks like. And while there are a number of result-based offences that make it a crime to have caused psychological harm, they're untested, hard to prove, and harder still to nail down.

“To date, not one person has been prosecuted in Australia for actually causing psychological harm to another person under the various result-based offences,” Paul McGorrery, a PhD Candidate in Criminal Law at Victoria’s Deakin University, told VICE over email. “Stalking laws, to my knowledge, have never been operationalised to target psychological abuse as you describe it, and we have no laws that specifically criminalise psychological abuse.”

Meaning, in short, that the best thing Australian law has to protect people against the predations of cults is a motley assortment of straw men and paper tigers.

This is what Nathan—the self-proclaimed optimist, empiricist, and reluctant agnostic—is fighting for in his new life as a politician. Nathan was elected a Councillor on Hawkesbury City Council in 2016 and stood for Liberal preselection for the NSW State seat of Hawkesbury in 2018. Now he wants governments to adopt meaningful laws around where religious freedoms start and end, and to actually prosecute people who inflict psychological harm.

“Nothing does more damage to mainstream religious denominations who do good work in the community than bad apples who poison the well,” he explains. He also wants to see bodies like the Australian Charities and Not for Profits Commission and the Tax Office to apply a more stringent Public Benefit test, and the establishment of a formal body that examines radical religious groups with more scrutiny.

Reforms like these have become a quest in his public life—even if he’s long since given up the fight to rescue his own wife from the perils of religious fundamentalism.

“I stopped fighting for Kylie when, three or four years down the track, I gave myself permission to be happy with the shape of my life,” he says. “In the immediate aftermath of her disappearance, I was fervent in what I characterised as rescuing my wife from a diabolical situation. But by degrees I came to realise that, to quote Voltaire, ‘you can’t rescue somebody that loves their chains’. Eventually you have to abandon people to their fate.”

You can see the Blue Mountains from where Nathan lives with his now-18-year-old son, Liam, in the Hawkesbury region of western Sydney. Liam is in Year 12 now, Nathan having raised him as a single parent with the help of his own family as well as Kylie’s. He’s done well in life, he admits. He’s happy.

Eleven-and-a-half years since Kylie backed down the driveway for the very last time, Nathan has reclaimed some form of the pleasantly conventional existence he once held so dear—albeit, with a few caveats. He’s learned that an ordinary life isn’t insulated against extraordinary events; that faith is not the same as kindness or virtue; and that devotion, particularly extreme devotion, can be co-opted as a force for both good and evil.

He has come to these lessons the hard way, through extreme and improbable circumstances. But anyone who finds his story unimaginable is missing the point.

“If you look at the worst examples of cults—Jonestown, Heaven's Gate, Waco and so forth—you'd have to ask: what brings people to that fever pitch, where their beliefs become delusional?” he says. “And it's a very uncomfortable thing for us to grapple with as a society that people—ordinary people—can be induced to do that. It's the same moral debate that asks why good people permitted Nazis to feed people to the gas chambers.

“Ordinary people can do very bad things,” he concludes. “And as Christopher Hitchens always said, if you want good people to do very bad things then what you need is religion. Religion is the only force in the world that can cause good, mild, boring people to commit atrocities.”

Virginia and her sistren have since disappeared back into the woodwork. Nathan suspects his long campaign of exposure has all but destroyed the group’s standing in the community, and forced them to go underground. But he also worries that there are more atrocities to come.

“One day, this group will so badly abuse somebody—whether it’s Kylie or somebody else—that someone will come to harm or die,” he portends. “And then if there’s a coronial inquest, the information given to me makes them incredibly culpable.”

As for his current feelings toward Kylie, the word Nathan lands on is pity—“pity in the same way someone might feel pity for a person who has been dealt a very bad hand in life, or made poor life choices, and is now reaping the consequences”. Pity and nothing else.

Liam, he says, feels utterly apathetic towards his mother, who is by now a dimming memory. It wasn’t until he was in his late teens that he asked to know the truth about everything that had happened. And Nathan, having protected him from it his whole life, finally handed him the source material.

“He went through all of the articles,” Nathan says. “And from his perspective, religious people stole his mother. So now he wants nothing to do with organised religion—because if that’s religion, you can have it.”

They’ve both long since moved on with their lives. But that doesn’t mean Nathan’s completely closed the book.

“I’ve characterised this as a missing persons case, in the sense that if a person dies you’ve got closure, but if a person goes missing then you lack even that closure,” he explains. “Somebody is out there with that person’s face, but not even going by that person’s name anymore. A shell of the person they used to be. A walking, human tragedy.

“I don’t want it to get to a coronial inquest before the truth is known,” he continues, “but I’ve also reconciled myself over the years to having many questions that I may never know the answers to. Why did these people do what they did? Why did Kylie choose to do what she did? Where will this all end? I do not know.”

If you or a loved one has experienced a situation like this, resources are available to help.

The Cult Information and Family Support Network and the Australian False Memory Association are Australian voluntary organisations. Immediate counselling help can be found at Lifeline, and Nathan invites contact through his own website.

from VICE US https://ift.tt/3heKQU4

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment