In February 1998, the naked bodies of three pubescent boys were found on a scrubby hill, just outside the town of Génova in central Colombia. The region is mountainous, semi-rural, and around 68 degrees by day, so the bodies were dark and bloated. The three boys had been bound at the wrists, and their necks looked like they’d been lacerated with a knife. Their penises had also been severed off, while all three bodies were covered in bite marks and showed signs of anal penetration. A discarded bottle of lube was found nearby.

It soon emerged that the three boys were poor, aged between 11 and 13, and had been good friends. The most disquieting detail came from one of the boys’ mothers, who said that her son had rushed home on the day he’d disappeared, claiming he’d been offered work from a man who needed help transporting cattle. Excited, he had left mid-morning on Friday. His body was found Monday.

Back in 1998, Duran Saavedra Aldemar was a 31-year-old criminal investigator with the Fiscalía General de la Nación—the Colombian version of the attorney general’s office—in the state of Quindio. On a whim, he checked the state’s records for similar cases and found an additional 13 unsolved cases stretching back years. All bodies of various poor and destitute boys were found with knife wounds to the neck, chest and groin, and many showing evidence of sexual assault. From there, Aldemar expanded the search to neighbouring states to discover that the bodies of young boys had been appearing on Colombia’s forested hills since at least 1992. In total, 13 of Colombia’s 32 states had at least one case that matched the profile, which seemed like fairly compelling evidence that the country was dealing with a serial killer.

And yet, somehow, Aldemar’s seniors disagreed.

“Our directors did not believe or imagine that there could be a serial killer here,” Aldemar tells VICE News over the phone, recalling several frustrating meetings with his director. “For us, 20 years ago, a case with these criminal characteristics was something like out of a soap opera, or a film. We never imagined we had serial killers in Colombia.”

For any westerner who has grown up in a culture that has mythologised serial killers since the 1970s, the notion that a police department could find such a pattern of murders and not suspect the worst seems absurd. And yet, this is what happened.

This case was a turning point for both the Colombian Police’s ability to identify the signs of serial homicide, but to also realise that the country had a unique problem. Because not only had Colombia dealt with serial killers before, they had also hosted some of the world’s most prolific.

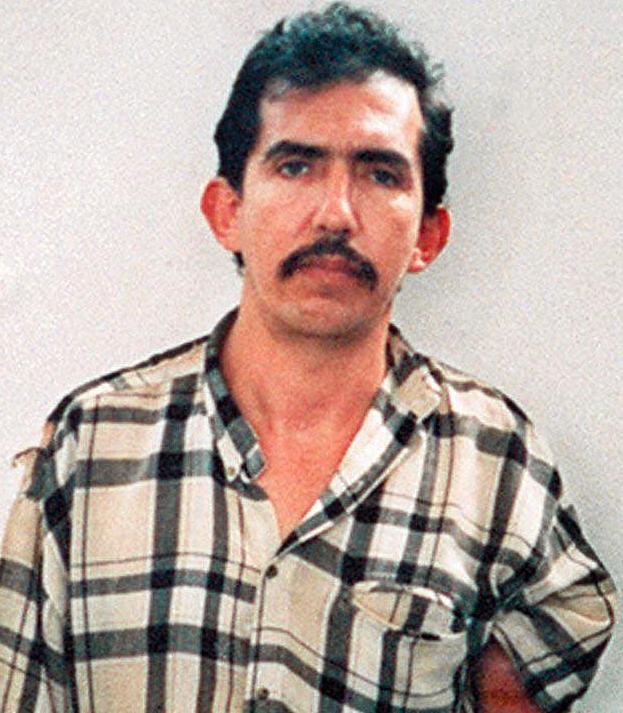

When Aldemar and his team found the killer, he turned out to be a 42-year old drifter named Luis Garavito. Garavito would befriend young boys and lure them into isolation by offering them small jobs, only to torture, rape and kill them. When he finally confessed to his crimes in 1999, he was attributed an official kill-count of 138, making him the world’s most prolific murderer—a record he still holds today*

But that wasn't a whole lot more than Pedro López, a fellow Colombian who’d killed some 110 young girls, just 20 years earlier and today still claims the number two world record. And then there was Daniel Camargo Barbosa, who throughout a similar period as López, had strangled young girls in Colombia and Ecuador. He had 71 confirmed victims, which placed him at number five on this rather ugly Wikipedia page titled “list of serial killers by number of victims”.

Together, these Colombian men hold three of the world’s top five records for homicide. They aren’t men associated with the country’s blood-soaked cocaine trade, nor were they involved in any military junta. Instead, they were motivated by a psychopathic and sadistic compulsion to kill, which they did unimpeded for years around a justice system that didn't take much notice.

The question is: why Colombia? What is it about this small, devoutly-Catholic nation that has produced and harboured such monsters?

The case of Luis Garavito holds some answers.

When Detective Aldemar took his evidence to his seniors and explained his serial killer theory, they responded with incredulity not because the violence was unusual, but because it wasn’t the type they were used to.

“We were more interested in investigating massacres and events that were causing national shock,” he recalls. “In Colombia, we have endured many types of violence: political violence, armed conflict violence, and so in some ways [this violence] allowed certain characters to operate in secrecy. It meant that we could not identify, stop, capture or construct a body of evidence around their cases.”

What Aldemar is referring to is the way violence had been almost normalised in Colombian society. It’s a history worth briefly examining to understand how consecutive serial killers could “operate in secrecy”.

Colombia achieved independence from Spain in 1810 but never truly achieved political stability. The 19th and 20th centuries were marked by a series of skirmishes and revolutions, which after WW2 spiraled into a period of widespread political aggression known as “La Violencia.” When the Liberal presidential candidate was assassinated in 1948, retributional violence between the two leading political parties killed an estimated 200,000 people.

The country never really recovered. A slow and torturous civil war took root, and another 220,000 people lost their lives over the half-century from 1958; a problem that was only exacerbated when the world discovered the coca plant growing on the Colombian Andes. The subsequent drug wars, combined with the country’s escalating armed conflict violence killed another 50,000 people.

By the 1990s, Colombians had developed “an uneasy coexistence with murder,” as crime prevention specialist Robert Muggah describes it. “It has become part of the fabric of life, normalized and even banalized.”

Muggah, who runs a think-tank working on data-driven justice across Latin America called Igarapé Institute, says that Colombia’s sky-high rate of homicide made it not just difficult to differentiate the victims of serial killers from all the other victims, but it made it incredibly hard for the police to investigate, much less prosecute perpetrators.

“In the 1990s and 2000s more than 20,000 people were killed a year,” he tells VICE News via email. “Police, prosecutors, public defenders and judges literally could not keep up with all the corpses.”

Finally, in 2016, a historic peace agreement was signed between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (also known as the FARC), leading many to believe the nation was entering a new period of peaceful stability.

But sadly, bloodshed in Colombia has continued unimpeded. Earlier this month, five teenagers aged between 14 and 18 were found with their throats slit after flying kites in the city of Cali. Just a week later, eight students were murdered when a group of hooded men fired into a crowded BBQ in Nariño. In each case, local gangs and drug cartels were held responsible.

The point is that today, as well as in the late 1990s, the rate of homicide in Colombia vastly surpassed the state’s ability to convict offenders, which left plenty of violent thugs on the loose.

“Colombia has exceedingly low clearance rates,” Muggah says, referring to the number of crimes that are “cleared” when a charge gets laid. “In Colombia, the clearance rate is about 10 per 100. So in other words, 90 percent of homicides in Colombia go unpunished.”

What Muggah suggests is that in Colombia, as well as many other parts of Latin America, prison time serves as little deterrent. This is a fairly unsurprising conclusion, but with a darker lining. Because if Colombia were a petri dish example of the way humans respond to lax law enforcement and normalised violence, the outcome seems to be more killers of every variety. And more killers who take lives more often.

Muggah tends to agree. He says the country’s rate of serial homicide “is not genetic, as some academics have suggested. Nor is there some intrinsic cultural factor that makes Colombians more violent than their neighbors in Chile, Ecuador, or Panama.

“Instead, I think that we can just expect to see a higher likelihood of serial killings in countries with lax law enforcement, low clearance rates, high levels of impunity and the normalization of violence.”

When Detective Aldemar was trying to build a profile of serial killer Luis Garavito in 1998, he personally experienced why murder cases so rarely get cleared. For him, the main problem was departmental siloing within the government.

In 1998, the attorney general’s office was a relatively new concept and they were in direct competition with the police, who in many cases refused to share information. Then on top of that was a complete lack of nationalised process. “These days the information is in databases and information systems,” he says. “But back then, we just had a pen and a diary and we’d make notes. Everything was analog.”

Even by the time he’d convinced senior management that they were dealing with a serial killer, he still wasn’t sure what that meant. He knew about serial killers from movies, and the old detectives who’d worked on the cases of Pedro López and Daniel Camargo Barbosa in the 1970s, but he had no specialised training. So he set about a course of self-education.

“Initially we had to read many books,” he says. “American literature, English literature that talked about the FBI and this particular type of criminal behaviour.”

He mentions one TV show that helped in particular: HBO’s 1995 crime series Citizen X, starring Donald Sutherland. The plot followed a detective battling an orderless bureaucracy to bring down a serial killer in Soviet Russia. As Aldemar says, “It was very similar to what we were observing.”

Finally, after about a year on the case, they had a breakthrough. They were contacted by a man who said he’d been attacked as a young boy by someone who’d promised him work moving cattle. But instead of work, he’d been tied up, raped, and tortured. Luckily, the attacker was so drunk that he’d fallen asleep, allowing the boy to escape.

Almost a decade later, this boy—now in his late teens—was buying lunch in a restaurant when he realised the cashier was the man who’d attacked him. Very quietly, he left the restaurant and went home to round up his uncles, who returned expecting a confrontation. But by that point, the man, who’d also recognised his victim, had walked off the job and disappeared. This man in his late teens didn’t know where his attacker went, but he knew the name of the restaurant: La Arepa.

From there, Aldemar interviewed the former restaurant owner, who was able to provide a description and a name of his former cashier. His name was Luis Alfredo Garavito.

Aldemar and his team weren't able to locate Garavito, but they found his sister in a town named Trujillo, only two hours west from where the three boys had been found in 1998. The sister was deeply religious and said she kept away from Garavito because he was so often drunk, but she referred the detectives to a school teacher he sometimes stayed with: a woman named Luz Mary who had several boxes of the killer’s possessions.

Aldemar opened the boxes to find newspaper clippings detailing missing children going back to 1992. Chillingly, they also found a calendar marked with numbers that ranged from nine to 14, scrawled on random dates. “We found out that he was marking the date and the age of the children he’d murdered,” says Aldemar.

Years later, after the conviction, they’d realise just how narrow Garavito’s victim profile was. They were always young boys with “blondish” skin and hair, with blue or green coloured eyes. They were never children of colour, and only once did they identify a victim with a slight disability. “He liked children with cute faces,” Aldemar says. “They were children who were interested in making some income to bring back to the family, children who liked to hustle.”

Aldemar and his team finally caught up with Garavito after the killer bungled an abduction. It was in the city of Villavicencio, near Bogotá, where guerilla fighting had intensified and Garavito’s victims were less conspicuous. There he met a boy selling lottery tickets on the street and offered the boy a job moving cattle, as per his usual modus operandi. He then attacked the boy in a vacant lot. A homeless man saw the attack and started throwing rocks at Garavito, which attracted the attention of a taxi driver who put a call out over the city’s taxis. Garavito was arrested that day under a false identity, but Aldemar’s team saw the mug shots and realised they had their man.

The next step was to get a confession, which took around 24 hours. “He was slippery,” recalls Aldemar. When asked a question he would often ask for it to be repeated to buy some thinking time. “He had no feelings, no reactions, he wouldn’t get anxious or nervous.”

Finally, Aldemar said he got a confession by pretending the detectives knew more than they did.

“I said to him: ‘Look, Luis Alfredo we know you are the one who killed all of the children, you are a good person… but when you drink you become cantankerous, aggressive. And in that moment, brother, is when you attack the minors.’”

Aldemar says the killer looked at him and cocked his head. “And he said to me, ‘Okay so tell me what else do you know?’”

From there Aldemar relayed the names of towns where they’d found bodies of children, the dates they’d likely been killed, and the evidence suggesting that Garavito had been the killer. Single graves, mass graves, and the stories of grieving mothers. It went on and on.

“Finally he looks at me and says, ‘You know what, yes’ and he stretched his arms in front… he said: ‘I want to apologise to the director and everyone here, and to the world, because I am a demon, and what you’ve found so far is nothing compared to what I’ve done.’”

Aldemar describes the team huddling in the attorney general offices of Villavicencio as the world’s most prolific serial killer described his crimes one at a time. They started at 7PM but didn’t finish until dawn the next day. In total, Garavito described between around 150 homicides, but authorities found sufficient evidence to convict him on only 138.

Garavito was later sentenced to 1,853 years and nine days in prison, the longest term in Colombia’s judicial history. However, it’s since been revealed that due to his willingness to help the police locate bodies, he may be released as early as 2023.

That particular issue is out of Aldemar’s control, but obviously he hopes Garavito will remain in prison. And he says that the Garavito case also prompted him to wonder what the country was doing to enable such vicious criminality.

“We also ask ourselves that question,” he says. “Why in almost all of Latin America, why are there more serial killer cases in Colombia?”

The answer he comes up with mirrors that of Muggah’s. He says it’s a tragic product of normalised violence and ineffective policing, but he is quick to argue that policing has improved.

“Twenty years ago, looking at these events was a novelty so we didn’t think it was only one human being doing this…. Fortunately, in the latest cases after Garavito we have been able to do better investigations.”

These days, Aldemar says the nation’s justice system is far more adept at recognising unique offenders and finding them. He’s proud of the way he helped design a formal framework for catching killers—particularly the way they borrowed criminal profiling techniques from the FBI, but adapted them specifically for Colombia.

“We noticed that the profiles done by the Americans would not work for us,” he says, “because Colombians are very different in the way they act, think, eat, and in their religious beliefs. So we started constructing our own profiles based on Colombia. We constructed profiles of the victims, the killer, the investigators, and what preparation a detective needs to have. We constructed something designed for us, which allowed us to start processing all of the information. We constructed a very well-organised information system; well-supported, well-directed, and this is what allowed us to start to connect this character to the victims we were finding.”

Aldemar is still a detective with the Fiscalía General de la Nación. He’s now in his 50s and he’s been there for a little over 30 years. His memories of the case have blurred but he still thinks about it often, and particularly of the victims’ families, which he says were effectively abandoned by the government. These days, he says such families would receive counseling services and financial assistance, but back then they were interrogated by police and forgotten.

“Unlike now, the state did not talk about reparation or financial compensation to the victims,” he says. “In [the state of] Quindio, we gave the victims some psychological support, but it was not an aid seen nationally. They never paid attention to it.”

Then, after a pause, he mentions the horror that some of these families were forced to endure. To him, that’s the real tragedy of the case: the swathes of people whose experience of life was irreversibly warped for the sake of one man’s entertainment.

“There were so many families who had found their children decapitated, stabbed, burned, bitten,” Aldemar says quietly. “Imagine, finding your child with a stick up their rectum all the way through their mouth, as a brother, as a father, as a mother—that is shocking. But [the police] never paid attention to it. This is my personal opinion, and you know I’m criticizing the state, which is the institution that pays my salary, but I still think there was a lack of help for these people—and especially for the families that were left.”

Follow Julian on Instagram and Twitter

Additional reporting by Laura Rodriguez Castro

*Harold Shipman, a doctor in the UK, technically claims the most victims after murdering hundreds of patients with overdoses of diamorphine. But as a physician, he was afforded unique freedoms and sits outside the traditional profile of a serial killer.

from VICE US https://ift.tt/3j1jgdy

via cheap web hosting

No comments:

Post a Comment